In November 2023, a groundbreaking radiocarbon study of Gezer established that the monumental phase of the city (known as Stratum 8) had been constructed during the 10th century b.c.e. after all—the same time period of King Solomon, to whom Gezer’s construction is credited in the Bible (1 Kings 9:15). The study thus settled, scientifically, a point of longstanding contention about the dating of this critical phase in the city’s history: whether the stratum should be associated with the 10th or ninth century b.c.e.

Numerous outlets reported on the discovery, including our own (“Gezer’s Carbon Speaks: Solomonic City After All”). Haaretz had its own take, titled “David and Solomon’s Biblical Kingdom May Have Existed After All, New Study Suggests.” Yet what piqued my interest the most was one of the comments posted to the article, in which a reader wrote:

There never was a David or Solomon in Palestine. When are you going to stop the nonsense of digging for any kind of evidence to justify Jewish the [sic] false biblical narrative. If Jewish archaeologists didn’t have tunnel vision, they would have figured it out long ago. The biblical stories were based on real historical events in another part of the Near East. They just aren’t researching. So pathetic.

Normally, I wouldn’t give such comments a second thought. Yet this kind of sentiment crops up fairly frequently. And it got me thinking: What if we didn’t have this “biblical narrative”? What if—for the purposes of this thought experiment—the Bible didn’t exist? Based on archaeological discoveries alone, how much would we actually know about ancient Israel?

Quite a lot, as it turns out. This article could be volumes long, but for our purposes, we’ll limit our study to inscriptions. And of these, we’ll highlight just a fraction of the more consequential examples—a sampling of the archaeological evidence from contemporary ancient texts.

What Would We Know?

We would know of the existence of a broad region of the Levant called “Canaan” during the mid-second millennium b.c.e. (for example, per the Statue of Idrimi, 15th century b.c.e.). We would know the names of dozens of cities in that region, such as Acco, Achshaph, Aijalon, Ashkelon, Beth-Shean, Byblos, Gezer, Hazor, Hebron, Jerusalem, Lachish, Megiddo, Shechem, Shiloh and Sidon (per the 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna Letters, which also describe major upheaval in the Canaanite lands, thanks to the invasion of a people at that time called Habiru). We would know of many more cities in Canaan, such as Aphek, Beth Shemesh, Laish and Rehov (per the Egyptian Execration Texts of the third to second millennium b.c.e.). We would also be aware of some kind of special, symbolic status to the city of Jerusalem, such that one would wish to “place his name in Jerusalem forever” (per Amarna Letter EA 287; compare with 2 Kings 21:7; 2 Chronicles 7:16; 33:4-7).

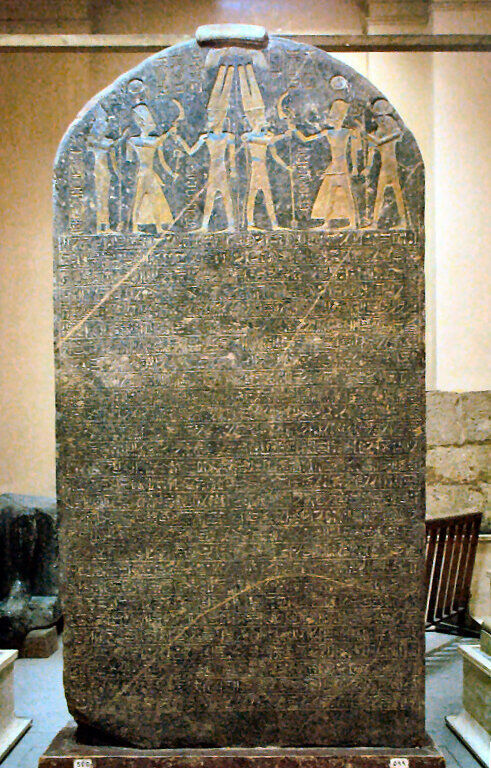

Sometime during the second half of the second millennium b.c.e., we would start to see a demographic change, and by the 13th century b.c.e., we would see our first confirmed reference to an entity named “Israel” within this territory, bordering Philistine land (per the Merneptah Stele, with another possible reference to “Israel” as early as the 14th century b.c.e. on the Berlin Stele).

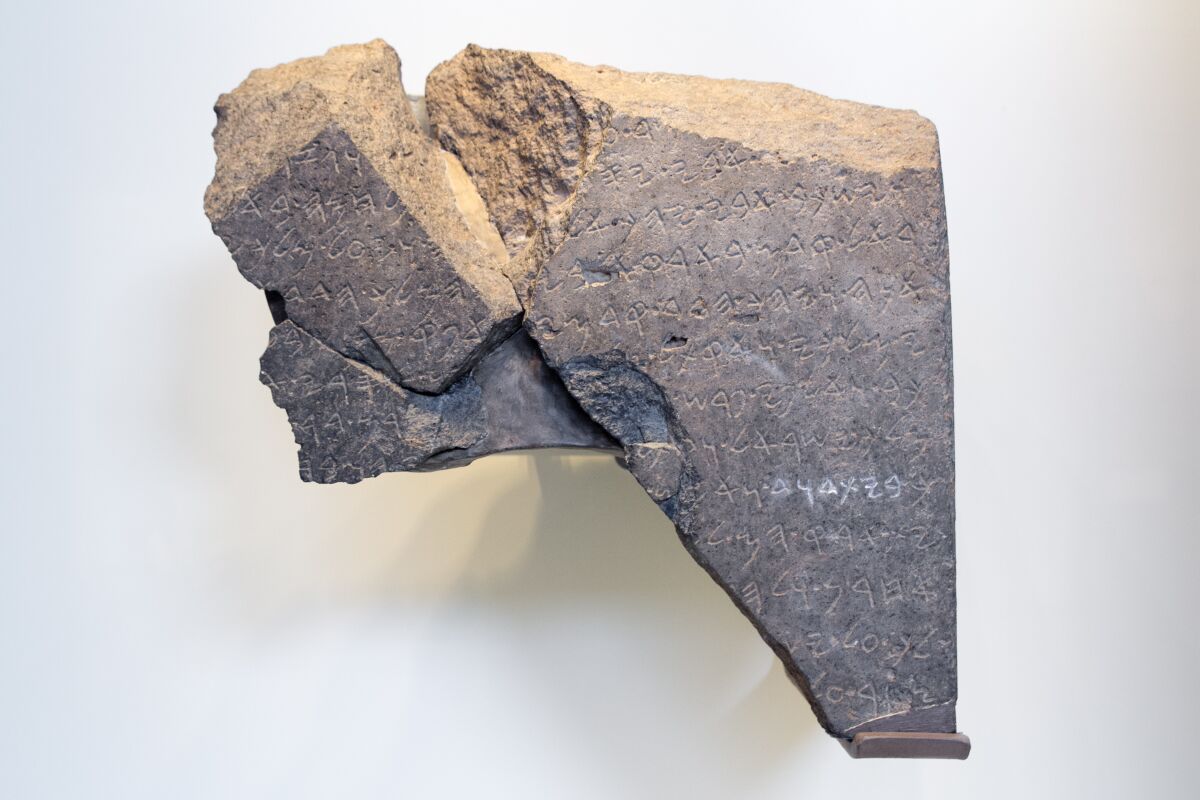

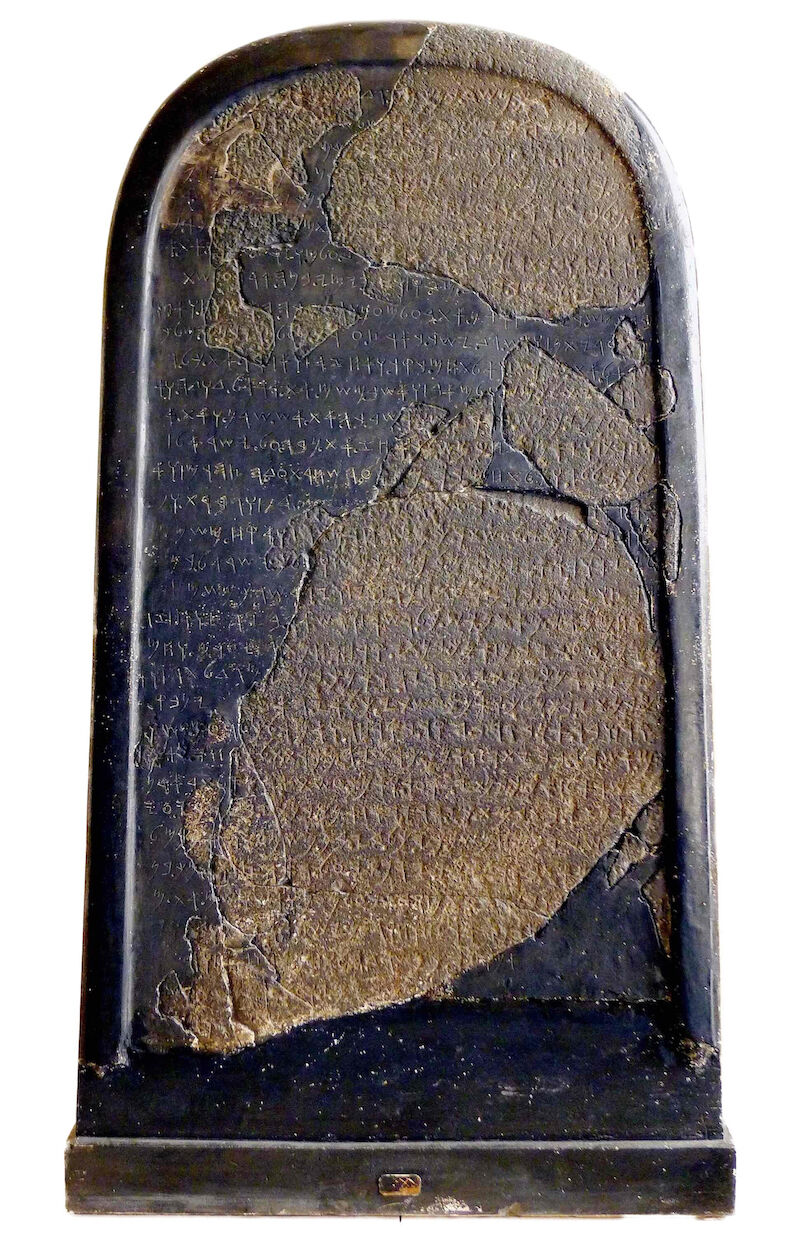

We would see certain internal, tribal-like divisions of the land, with one entity—“Judah”—located in the south, and another entity—“Gad”—living in the formerly Moabite territory of Ataroth, east of the Jordan River (per the Mesha Stele, ninth century b.c.e., which also states that these Gadites had been living in this land “from ancient times.” Compare with Numbers 32:34). By at least the ninth century b.c.e., we would start to see “Israel” as a separate, yet allied, kingdom alongside Judah (per the Tel Dan Stele, ninth century b.c.e.).

We would see a principal deity being worshiped in the land by the name of yhwh, Yahweh (as shown by numerous Iron Age inscriptions, including the Mesha Stele). This was the name used for the deity both “of Samaria” (per the Kuntillet Ajrud inscription, ninth century b.c.e.) and “of Jerusalem” (per the Khirbet Beit Lei graffiti, circa seventh to sixth century b.c.e.). We would also see this deity first recorded in ancient Egypt as being worshiped by eastern nomads more than 500 years earlier (per the Soleb Inscription). We would know that one of the specific titles for this deity was “Lord of Hosts”—Yahweh Sabaoth (per an eighth-century b.c.e. Judean cave stone inscription). And we would know of some kind of worship taking place in a “house of Yahweh” (per Arad Ostracon 18, circa 600 b.c.e.).

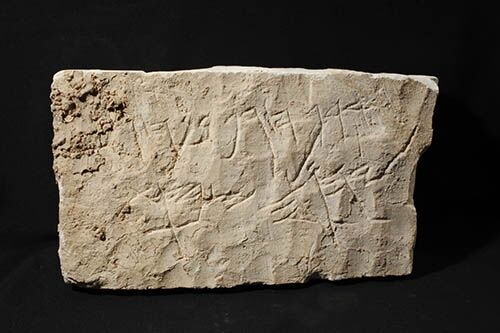

We would know of some kind of body of religious literature—poetry, wisdom, etc—belonging to these people (per the circa 600 b.c.e. “priestly blessing” Ketef Hinnom Scrolls—silver scrolls containing etched text paralleling, word-for-word, Deuteronomy 7:9 and Numbers 6:24-26). We would know of certain religious laws being observed and cited—even by menial laborers on the territorial fringes—including the keeping of a “Sabbath,” as well as mundane laws such as the confiscation and return of garments (per the Mesad Hashavyahu Ostracon, seventh century b.c.e.; compare with Exodus 22:26-27 and Deuteronomy 24:10-15).

Rulers We Would Know

As far as governing administration goes, we would see the establishment in Judah of a royal dynasty belonging to a ruling progenitor named “David” (per the Tel Dan Stele and Mesha Stele, ninth century b.c.e., with a likely additional reference to David in the Karnak Inscription, 10th century b.c.e.). We would see the establishment of a royal dynasty in the northern kingdom, Israel, belonging to a ruling progenitor named “Omri” (per the Moabite Mesha Stele, along with roughly a dozen other Assyrian inscriptions referencing the “House of Omri” and “Land of Omri” and dating to the ninth and eighth centuries b.c.e.).

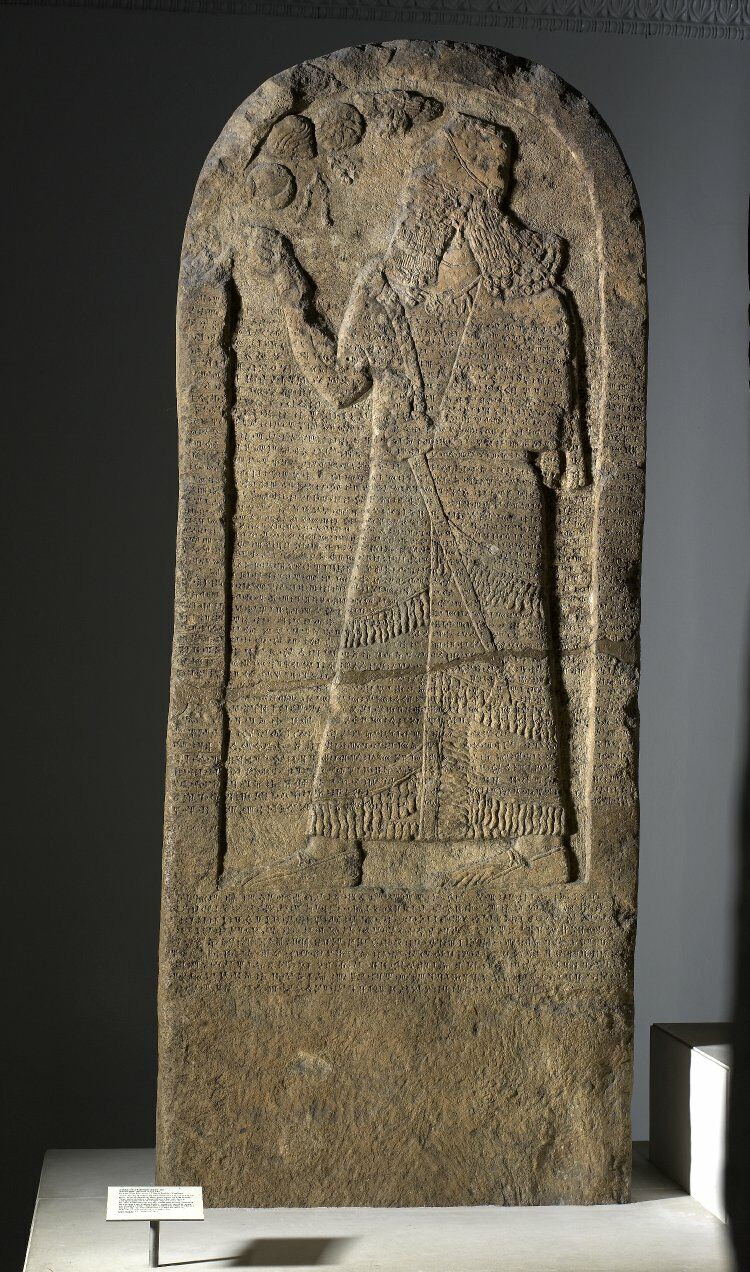

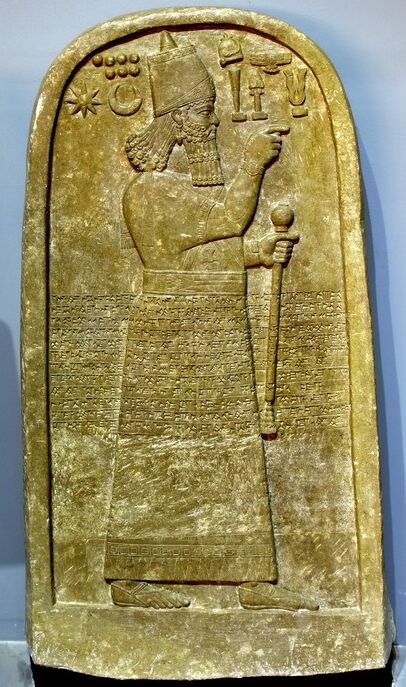

Sometime during the latter half of the 10th century b.c.e., we would see an immense campaign into the Levant by the Egyptian Pharaoh Shoshenq i, conquering numerous cities within this territory of Judah and Israel (per his Karnak inscriptions; compare with 1 Kings 11:40; 1 Kings 14:25; 2 Chronicles 12). In the century following, we would see an early, powerful king of Israel named “Ahab” on the scene, fielding an immense army of soldiers, horses and chariots, and allied with a king of Syria (per Shalmaneser iii’s Kurkh Monolith; compare with 1 Kings 18:5; 20:1, 34).

We would know of a temporarily successful Moabite attempt to shake off Israelite rule by King Mesha (per the Mesha Stele and Khirbat Ataruz Altar Inscription; compare with 2 Kings 3). Also during the ninth century b.c.e., we would see a Syrian king’s defeat of the allied kings of Israel and Judah, per the Tel Dan Stele—the ruler of Israel on the inscription bearing the defaced name “[…]ram” and the ruler of Judah “[…]iah” (compare with the biblical account of the demise of Israel’s Joram and Judah’s Ahaziah against the backdrop of battle with Syria’s Hazael in 2 Kings 8-9).

We would subsequently see the appearance of a king in Israel named Jehu (per Shalmaneser iii’s Black Obelisk and Kurba’il Statue, ninth century b.c.e.). And at the end of that century, we would see a ruler assume the throne of Israel, based in Samaria, named Jehoash (per the Tell al-Rimah Stele).

During the ensuing eighth century, we would see the rise of a ruler named Jeroboam in Israel (per the Megiddo seal) and a Uzziah/Azariah reigning over Judah (per the seals of Abijah and Shebnaiah, as well several inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser iii; note also the Uzziah Tablet). We would see a series of final kings ruling Israel from Samaria during the mid-to-latter part of that century: Menahem (per the Calah Annals and Iran Stele), Pekah (several artifacts, notably Tiglath-Pileser iii’s Summary Inscription 4), and Hoshea (Summary Inscription 4). Finally, we would know that in 718 b.c.e. an Assyrian king named Sargon completed the Assyrian siege of Samaria and carried the occupants into captivity (as relayed in the annals of Sargon, such as Nimrud Prism 4; compare with 2 Kings 16-17).

In Judah, during the latter part of that century, we would see the rule of a king named Ahaz (per Tiglath-Pileser iii’s Summary Inscription 7, as well as the Ahaz, Hezekiah and Ushna seals—the former also referencing Ahaz’s father, King Jotham). We would see this king succeeded by a ruler named Hezekiah (per the Hezekiah bulla, as well as numerous inscriptions from Assyrian King Sennacherib). We would also see this King Hezekiah in some kind of proximity to an official named “Isaiah […] Nabi[?]” (i.e. “prophet,” per the Isaiah bulla).

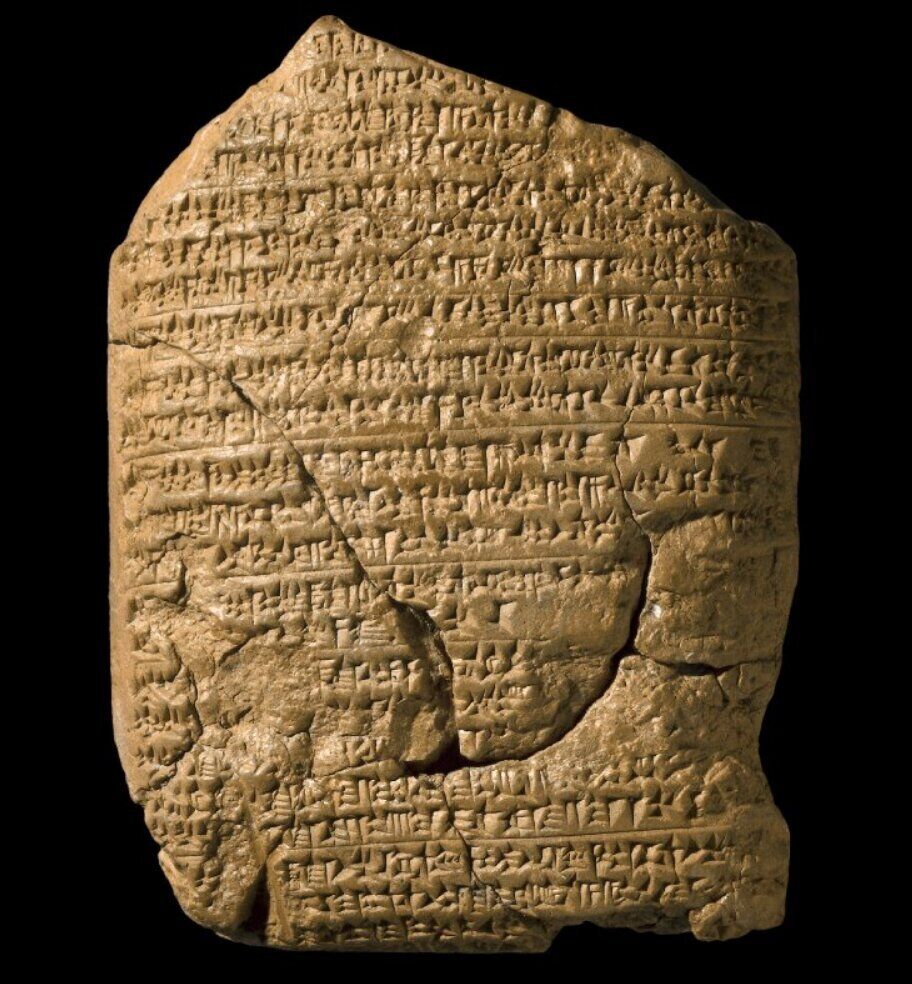

We would see that during Hezekiah’s reign, at the end of the eighth century b.c.e., Sennacherib began a conquest of the Levant, destroying 42 Judahite cities and barricading Hezekiah “like a caged bird” in Jerusalem (per Sennacherib’s trio of prisms: Taylor, Oriental Institute and Jerusalem). We would know that Hezekiah had paid a heavy tribute to Sennacherib in order to placate him, which included “30 talents of gold” (per Sennacherib’s Winged Bull Inscription; compare with 2 Kings 18:14).

We would also see, around this same general timeframe, the hewing of a monumental water system in the City of David (per the Siloam Tunnel and Siloam Inscription), which would lead us to conclude that this was likely for some kind of defensive purpose, in order to protect and consolidate the vulnerable waters of the outer Gihon Spring (compare with 2 Kings 20:20 and 2 Chronicles 32:3-4).

We would also know that, despite his capture of Judah’s “second city,” Lachish (as prominently displayed in relief form on his palace walls at Nineveh), there is suspiciously no mention or evidence of Sennacherib conquering Jerusalem itself. We would see this explained as the product of divine intervention—a plague that suddenly wiped out 185,000 of Sennacherib’s men—in the writings of the third century b.c.e. Babylonian historian Berossus (compare with 2 Kings 18-19; 2 Chronicles 32; Isaiah 36-37. We would also see a rather similar miraculous account in the writings of the fifth century b.c.e. Greek historian Herodotus).

On into the seventh century b.c.e., we would see the rule of a Judahite king named Manasseh, with a certain tributary dependence on Assyria (per Esarhaddon’s Prism B and Ashurbanipal’s Cylinder C; compare with 2 Chronicles 33:10-13). We would see a number of princely/priestly/administrative Judahite officials begin to appear during the latter part of that century, including Nathan-melech, Hilkiah, Azariah, Shaphan, Gemariah, Shelemiah, Jehucal, Pashur and Gedaliah (per a number of bullae discovered during excavations of the City of David; compare with 2 Kings 23:11; 1 Chronicles 6:13; Jeremiah 36:12; 38:1).

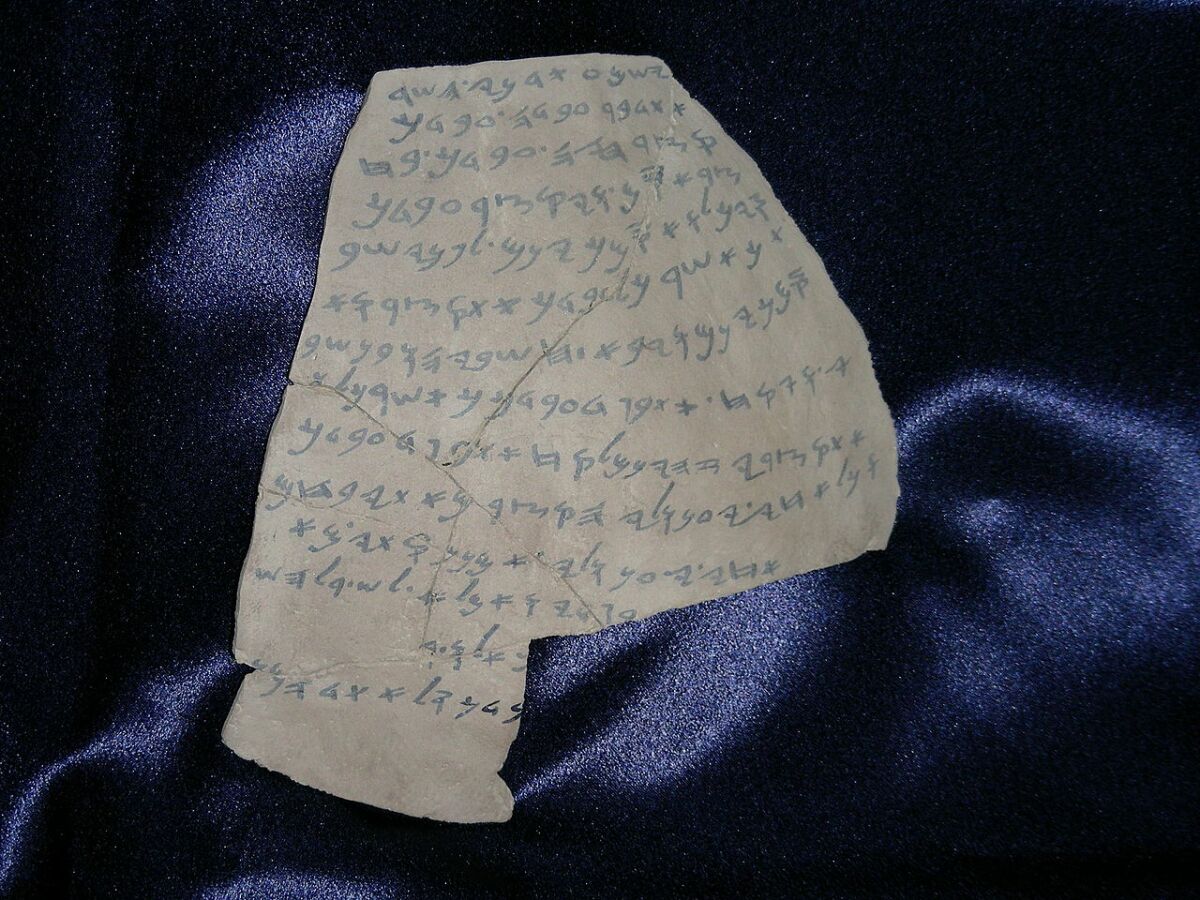

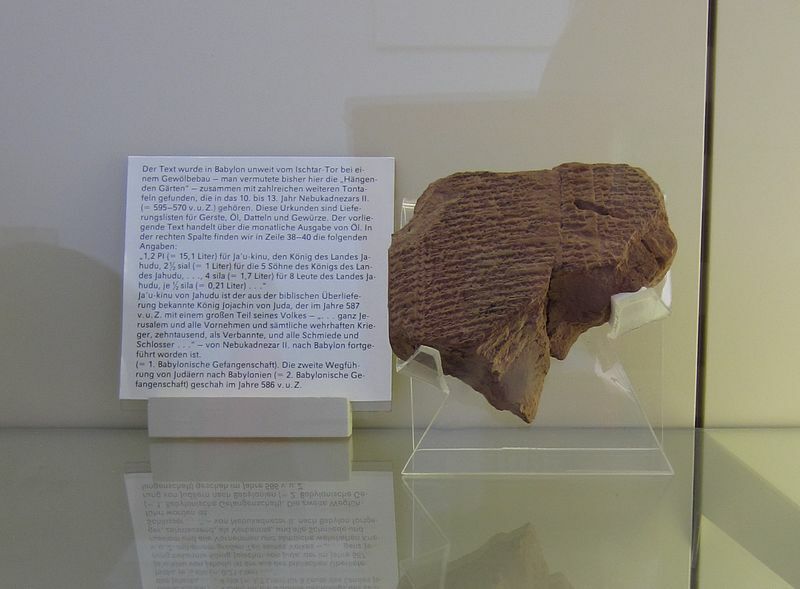

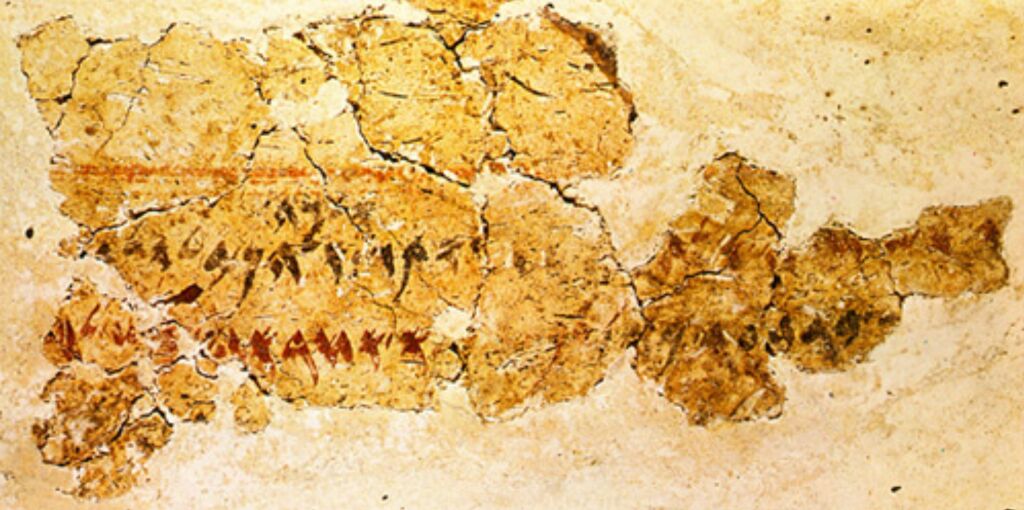

We would see, at the turn of the century, the rise of a Babylonian king named Nebuchadnezzar and his capture of a king of Judah named Jehoiachin, who was taken into captivity and issued favorable rations and treatment (per the Rations Tablet, among several other inscriptions; compare with the biblical description of Jehoiachin’s rations and treatment in 2 Kings 25:27-30). We would see Nebuchadnezzar’s installation of a puppet king in Jerusalem during this campaign in Year 7 of his reign (circa 597 b.c.e., per the Babylonian Chronicle; compare with 2 Kings 24:27). We would know, from correspondence among Judahite military commanders, the desperate situation in the land due to the Babylonian invasions (per the Lachish Letters), along with certain warnings from a “prophet” in the land (Lachish Letters iii and xvi; the latter, badly-damaged letter referencing “[…]ah the prophet”; compare with the biblical Prophet Jeremiah on the scene during this time).

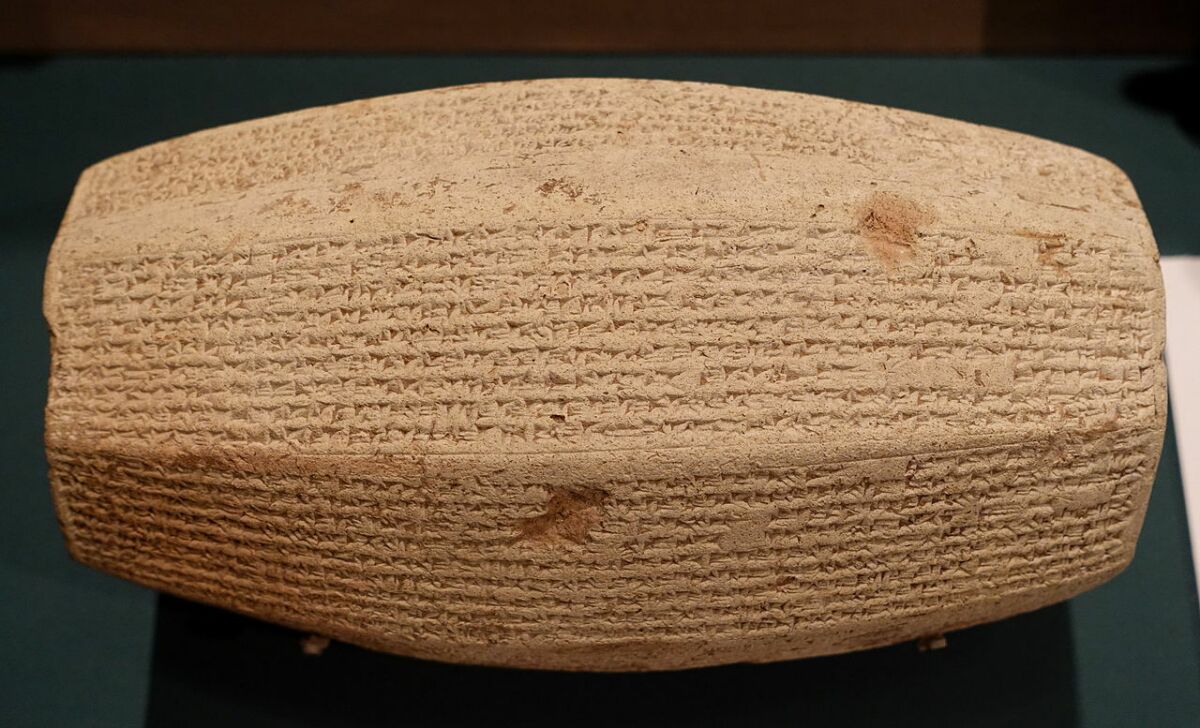

We would know that ultimately, the kingdom of Judah finally collapsed during this first half of the sixth century b.c.e., Jerusalem succumbing to a fiery destruction circa 586 b.c.e. Its administration was replaced by a short-lived Babylonian one, which was followed soon after by Persian control under the leadership of King Cyrus. And we would know that Cyrus presided over a benevolent “right of return” policy for defeated peoples to regather and rebuild their temples (per the Cyrus Cylinder; compare with Ezra 1:1-4). We would shortly thereafter see the land come to be referred to in various inscriptions as “Yehud,” and the reemergence there of a Jewish, Jerusalem-based administration and priesthood, with connections to Jewish communities as far away as the Nile River island of Elephantine in Upper Egypt (per the Elephantine Papyrus, late fifth century b.c.e.).

… And On and On

Our list could go on. Again, this is just a small percentage of the inscription-based discoveries, particular to the nations of Israel and Judah. Many more could be given, both for these entities, and entities further abroad.

What about the five different named biblical pharaohs, all confirmed by archaeology: Shishak (Sheshonq i), So (Orsokon iv), Tirhakah (Taharqa), Necho (Neco ii) and Hophra (Apries)? What about the five biblical kings of Syria who have been confirmed archaeologically: Hadadezer, Ben-hadad (son of Hadadezer), Hazael, Ben-hadad (son of Hazael) and Rezin? What about the five Assyrian kings confirmed archaeologically: Tiglath-Pileser iii, Shalmaneser v, Sargon ii, Sennacherib and Esarhaddon—as well as Prince Adrammelech? What about the four Babylonian kings confirmed by archaeological discoveries: Merodach-baladan ii, Nebuchadnezzar ii, Evil-merodach and Belshazzar—as well as the Babylonian officials Nebo-sarsekim, Nergal-sharezer and Nebuzaradan? What about the five Persian kings: Cyrus ii, Darius i, Xerxes i, Artaxerxes i and Darius ii—as well as governors Sanballat and Tattenai? What about the Moabite King Mesha? What about the Ammonite King Baalis and the Prophet Balaam, son of Beor? (Read more about these individuals, and several others, in Prof. Lawrence Mykytiuk’s “53 People in the Bible Confirmed Archaeologically.”)

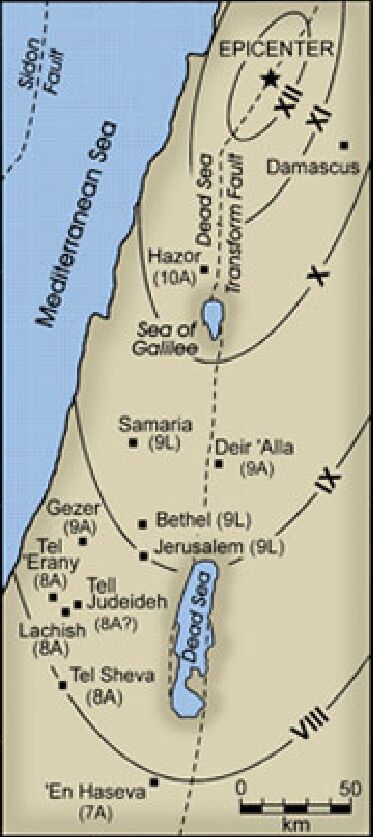

What about the many more, non-inscriptional archaeological discoveries? The immense amount of mid-eighth century b.c.e. earthquake damage, relating to “Amos’s Earthquake.” The archaeozoological evidence in Iron Age Israel pointing to the existence of some kind of “kosher” rules in place. The rise, fall and destruction of various cities themselves in the aforementioned biblical locations—from Jerusalem to Hazor to Gath.

Of course, there would be the conceivable objection that without the framework of the biblical account, such artifacts would be more difficult to contextualize (for example, with the exact order of certain biblical kings). There would also be the objection that were it not for a level of interest in the Bible, many of the excavations from which these particular artifacts derive would not have been accomplished. Yet by the same token, one wonders how different archaeology would look as a whole, given the fundamental, formative influence that biblical archaeology has had on this field of science. And carrying along such a “what if” scenario to its fullest extent would be an exercise in abstract futility: Even our wider world would look entirely different—unrecognizable—without the Bible as the foundational text underwriting much of the history of Western civilization and its Judeo-Christian heritage. Would it be a more scientifically-based and rational world? Despite popular objections to the contrary, the evidence says no. In fact, much of modern science found its beginnings in Bible-based theology—with the belief that such a world could be studied and made sense of, because of a rational Lawgiver and Creator.

Sir Isaac Newton is a classic case in point—one of the early scientific “greats” who actually wrote more on biblical theology than he did science. And underwriting the studies of the great scientist, mathematician and “founder of modern Western philosophy,” René Descartes, was his view of the universe as “a great time machine operating according to fixed laws, a watch created and wound up by the great watchmaker.” In a real sense, therefore, we can no more entirely separate the Bible from archaeology than we can separate its effects on other fields of science.

Suffice it to say, then, that the above-described artifacts are but a tiny sampling of the extra-biblical, tangible contemporary remains history has left us with, which can be examined in their own right, quite independently of the Bible.

And what story do these artifacts tell us? One of “Jewish archaeologists” desperately scrabbling to find “justification” for a “false biblical narrative”? Such a conclusion is, of course, laughably false. Not least because most of these discoveries mentioned were not even found by Jewish archaeologists (and even the recent Gezer study commented on in the introduction was the product of excavations conducted by an institute based in Texas). These are artifacts that have been discovered by Christians, Jews, Muslims, and those of other religious persuasions—by agnostics, atheists, deists and theists—by Americans, British, Danes, Egyptians, French, Germans, Israelis, Jordanians—the list goes on.

With this immense—and constantly growing—corpus of material that has been discovered, one could write a veritable bible.