It’s an oft-repeated refrain in the Bible: the notion of God placing His name in Jerusalem forever. Notice, for example, the following passages:

- “[I]n Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, will I put My name for ever” (2 Kings 21:7).

- “For now have I chosen and hallowed this house, that My name may be there for ever” (2 Chronicles 7:16).

- “In Jerusalem shall My name be for ever” (2 Chronicles 33:4).

- “[I]n Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, will I put My name for ever” (2 Chronicles 33:7).

It’s a sentiment that can be easily overlooked. But it is one with a deep intrinsic meaning and, most intriguingly, with a remarkable parallel in the archaeological record.

Nearly 3,400 years ago, a besieged Abdi-Heba—the Canaanite ruler of Jerusalem—wrote the following desperate message to a 14th century b.c.e. pharaoh of Egypt, begging for his help as de facto ruler of the Levant: “As the king has placed his name in Jerusalem forever, he cannot abandon it—the land of Jerusalem.”

What could this fascinating parallel mean?

Calamitous Context

The similarities between the biblical statements and that of this ancient cuneiform inscription are immediately striking. Both refer to the same city. Both refer to the placing of one’s name in that city. And both refer to a timeframe—“forever.” Clearly, this was a well-established and extremely ancient sentiment applied to the city of Jerusalem.

This Canaanite “letter,” or rather squarish clay tablet, is one of the “Amarna Letters”—specifically, Amarna Letter EA 287. The Amarna Letters are a collection of nearly 400 cuneiform clay tablets found in the 14th century b.c.e. ancient Egyptian administration center of Amarna. The letters are attributed to the reigns of pharaohs Amenhotep iii and his son, Akhenaten. These clay tablets—most of which were found in 1887—constitute correspondence from the rulers of Canaan (modern-day Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria) to the pharaoh of Egypt, who had general control over Canaan at the time.

The Amarna Letters are rather famous in the debate about the historicity of Israel’s conquest of Canaan. Their date generally fits with the earlier, literal biblical chronology for the period of the conquest (c. 1400 b.c.e. on into the 14th century), and intriguingly, many of the letters from these Canaanite kings express consternation about a mysterious invading people called Habiru, pleading with the Egyptian pharaoh to send help. As in the following examples:

- Letter EA 286, from our above-mentioned Abdi-Heba, ruler of Jerusalem: “May the king [Egypt’s pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted. … Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord. … The king has no lands. The Habiru have plundered all the lands of the king.”

- Letter EA 299, from Yapahu, ruler of Gezer: “To the king, my lord … [s]ince the Habiru are stronger than we, may the king, my lord, give me his help, and may the king, my lord, get me away from the Habiru lest they destroy us.”

- Letter EA 288, from Abdi-Heba: “May the king give thought to his land [in Canaan]; the land of the king is lost. All of it has attacked me. … I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea …. [T]he Habiru have taken the very cities of the king. Not a single mayor remains to the king, my lord; all are lost.”

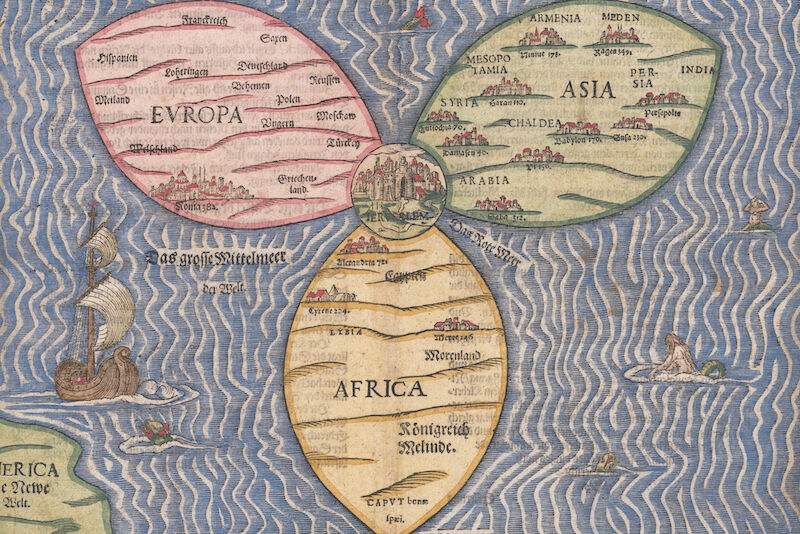

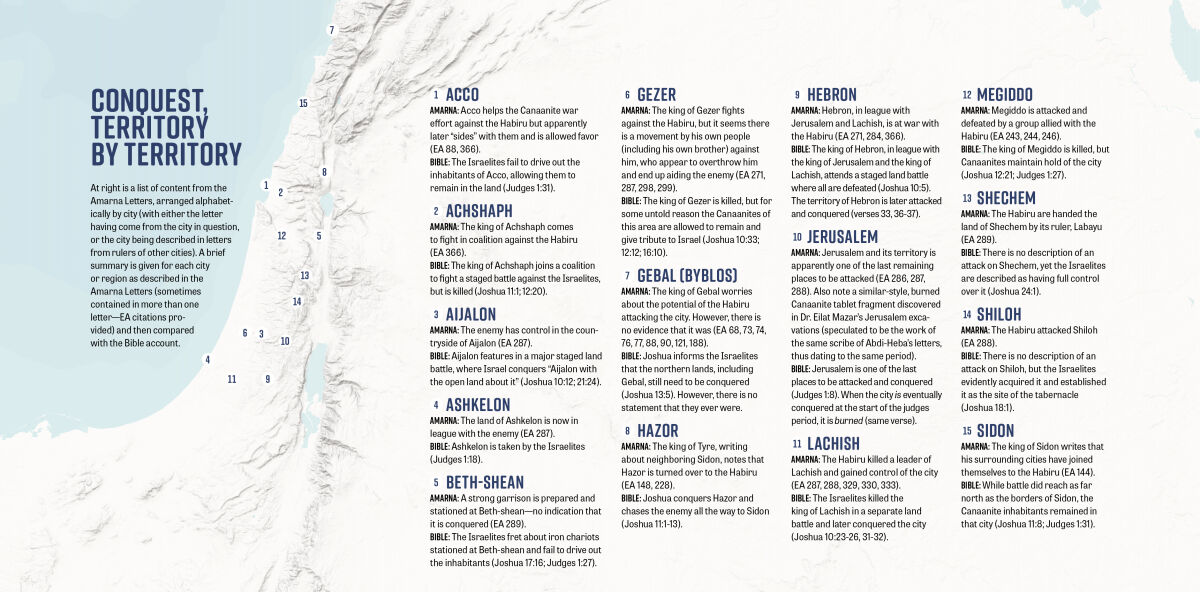

In our article “The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?,” we argue that these Habiru are the biblical Hebrews, that these letters do reflect the overall conquest of Canaan, and that there is a verisimilitude even on a city-by-city basis between the biblical account of the battles and the Amarna Letters, as summarized in the infographic below.

It is against this desperate backdrop that we have Letter EA 287 from Jerusalem’s Canaanite “mayor” Abdi-Heba: “May the king [Egypt’s pharaoh], my lord, know that I am unable to send a caravan [of tribute] to the king, my lord. For your information! As the king has placed his name in Jerusalem forever, he cannot abandon it—the land of Jerusalem.”

For what it’s worth, there appears to have been no real response from the Egyptian pharaoh, as the Habiru wrought havoc upon the cities of Canaan. And indeed, Judges 1:8 describes an eventual initial victory for the Hebrews against Jerusalem: “And the children of Judah fought against Jerusalem, and took it, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and set the city on fire.” The border city became ascribed to the territorial jurisdiction of the tribe of Benjamin, who “did not drive out the Jebusites that inhabited Jerusalem; but the Jebusites dwelt with the children of Benjamin in Jerusalem, unto this day” (verse 21).

Abdi-Heba’s message to the pharaoh, therefore, reflects a general context of turmoil for Jerusalem in his reminder that the ruler had “placed his name” in Jerusalem and, therefore, must save it.

But this was no ordinary pharaoh.

Akhenaten—Revolutionary Monotheist?

Again, the Amarna Letters are attributed to the reigns of pharaohs Amenhotep iii and his son, Akhenaten. And while it is somewhat ambiguous as to whom exactly EA 287 was addressed (it was commonplace in the New Kingdom period not to refer to the pharaoh by personal name—this is one possible reason why the Exodus pharaoh is likewise not named in the biblical account), there is a high likelihood that it was addressed to Akhenaten.

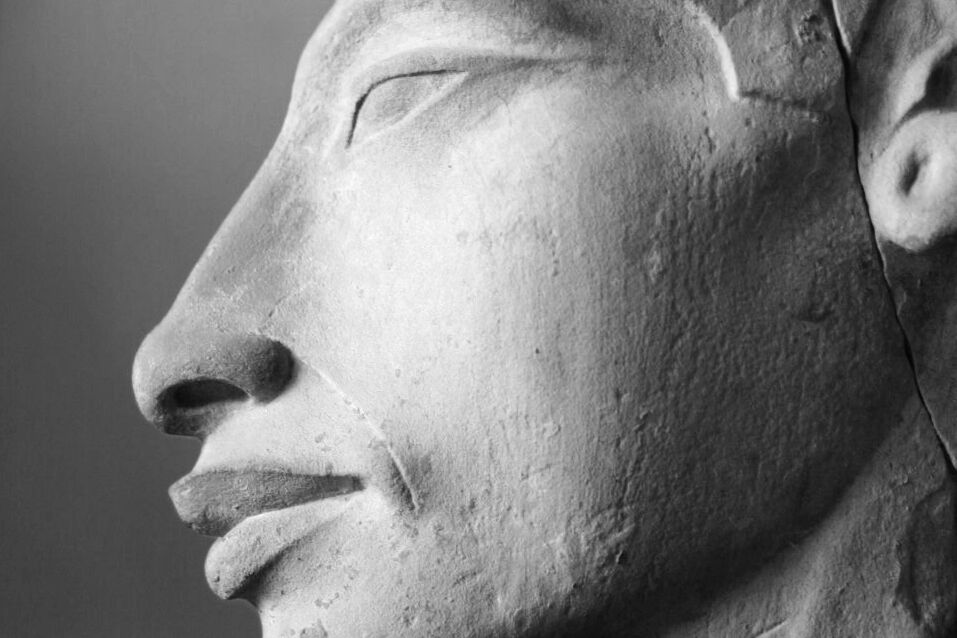

Akhenaten’s reign is noteworthy for this 14th century b.c.e. period of upheaval in Canaan. But it is even more noteworthy for another reason: During his reign, Egypt’s polytheistic religious system was entirely upended and replaced by an unprecedented swing toward a form of monotheism—specifically, the singular worship of the sun-god Aten. Akhenaten broke entirely with tradition and renamed himself after this deity—his original regnal name being Amenhotep iv.

This jaw-dropping, unprecedented upheaval in Egypt’s complex and ancient religious system continues to bewilder and fascinate scholars. Various researchers have labeled Akhenaten a “revolutionary,” a “heretic” and “fanatic.” Some claim he was “possibly insane.” Some, noting the Amarna Letters, which essentially document a failure to send military aid to Canaan, have called him a “pacifist.” What earthly thing caused this pharaoh to upend Egypt’s religious system?

A pylon inscription at the Karnak temple complex near Thebes records a jaw-dropping speech by Akhenaten. It reads, in part: “The temples of the gods are fallen to ruin, their bodies do not endure. … I have watched as they have ceased their appearances, one after the other. All of them have stopped, except the god who gave birth to himself. And no one knows the mystery of how he performs his tasks. This god goes where he pleases and no one else knows his going.”

Pharaoh Akhenaten’s speech reflects the total loss of faith in Egypt’s numerous gods. But this is only fitting: If the Amarna Letters of his reign (and that of his father) reflect the biblical conquest period, then it follows that the Exodus event dates within the decades prior—an event in which the God of Israel demonstrates His superiority “against all the gods of Egypt” (Exodus 12:12). You can read more about this in our article “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?”

As for Jerusalem?

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that against the backdrop of such a unique period of time we find reference to the pharaoh placing his name in Jerusalem, “forever.”

Actually, the general sentiment of “placing one’s name” is fairly well-attested in the ancient Near East. This is highlighted by Prof. Sandra Richter in The Deuteronomistic History and the Name Theology: lešakkēn šemô šām in the Bible and the Ancient Near East. She presents evidence that this “placing of name” took quite a literal form, with conquering rulers installing inscriptions bearing their name in their newly acquired territories. One example she highlights is that of Iahdun-Lim of Mari (c. 1830 b.c.e.), who set up a victory monument in the Amanus mountain range:

Iahdun-Lim, the son of Iaggid-Lim, the mighty king …. To the Cedar and Boxwood Mountain, the great mountains, he penetrated…. He set up a monument, placed his name and made known his might.

This terminology, of “placing one’s name,” would therefore have been readily recognizable for the ancient Israelites. What is notable about the biblical turn of phrase, though, is that it is not one associated with conquest. The placing of God’s name in Jerusalem is presented not as an addition to other territories, but rather, at the exclusion of all other sites. Again, for example, from 2 Kings 21:7: “[I]n Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, will I put My name for ever.” The sentiment is clearly metaphorical in nature. And there is also that additional specificity—that this choice of city for God’s name would apply “forever.”

Something, clearly, was special about this particular city, Jerusalem.

Could such a thing have also been recognized by our pharaoh? We can only speculate. But it is interesting just how closely EA 287’s terminology parallels that of the Bible’s—not only in the general “placing of name,” but also in the location, Jerusalem, as well as in timeframe—“forever.” Added to this is the aforementioned intrigue of the pharaoh’s religious revolution, as well as the fact that neither Akhenaten, nor his father Amenhotep iii, are known as conquering pharaohs. Both are often described as pacifists, and both are known for single campaigns during their reigns (against Egypt’s southern neighbors, the Nubians).

How, then, did the pharaoh’s name come to be “placed in Jerusalem forever”? It is interesting that in our Amarna letter, it is the Canaanite ruler of Jerusalem reminding the pharaoh of this. Could these rulers have been acknowledging some prior-established, long-recognized sanctity to the city of Jerusalem, one which included this symbolic sentiment of placing one’s name therein, forever?

Enter Melchizedek

But such a sanctity is already highlighted in the biblical account from the beginning, with the very foundation of the city by “Melchizedek king of Salem … priest of the most high God” (Genesis 14:18; King James Version. Note Salem as the original name for Jerusalem; see also an equivocation in Psalm 76:2).

Speculation abounds as to the identity of this Melchizedek to whom Abraham paid tithes (Genesis 14). One traditional rabbinic opinion is that he was Shem (who, according to the ages given in Genesis 11, would have still been on the scene during the lifetime of Abraham). One Christian view is that, building off of Psalm 110, he was the promised Messiah, the one who became Jesus Christ (Hebrews 5-7, cf. John 8:57-58). A remarkably similar opinion, in several respects, has also been found among the Jewish Qumran community of the second and first centuries b.c.e.

The Dead Sea Scroll 11QMelch (circa 100 b.c.e.) identifies Melchizedek with the term “Elohim” (citing Psalm 82:6), also the “anointed one” of Daniel 9, and as one who would make an atonement for sins. It further adds that, at the “end time,” he would usher in salvation and the true fulfillment of the Leviticus 25 “Jubilee,” overthrowing the evil spirit “Belial” and his forces. And again, another somewhat related connection can also be found with the first century b.c.e. Jewish philosopher Philo, who referred to Melchizedek with the Greek title “Logos.” The same title is also linked to Jesus in the New Testament (i.e. John 1:1).

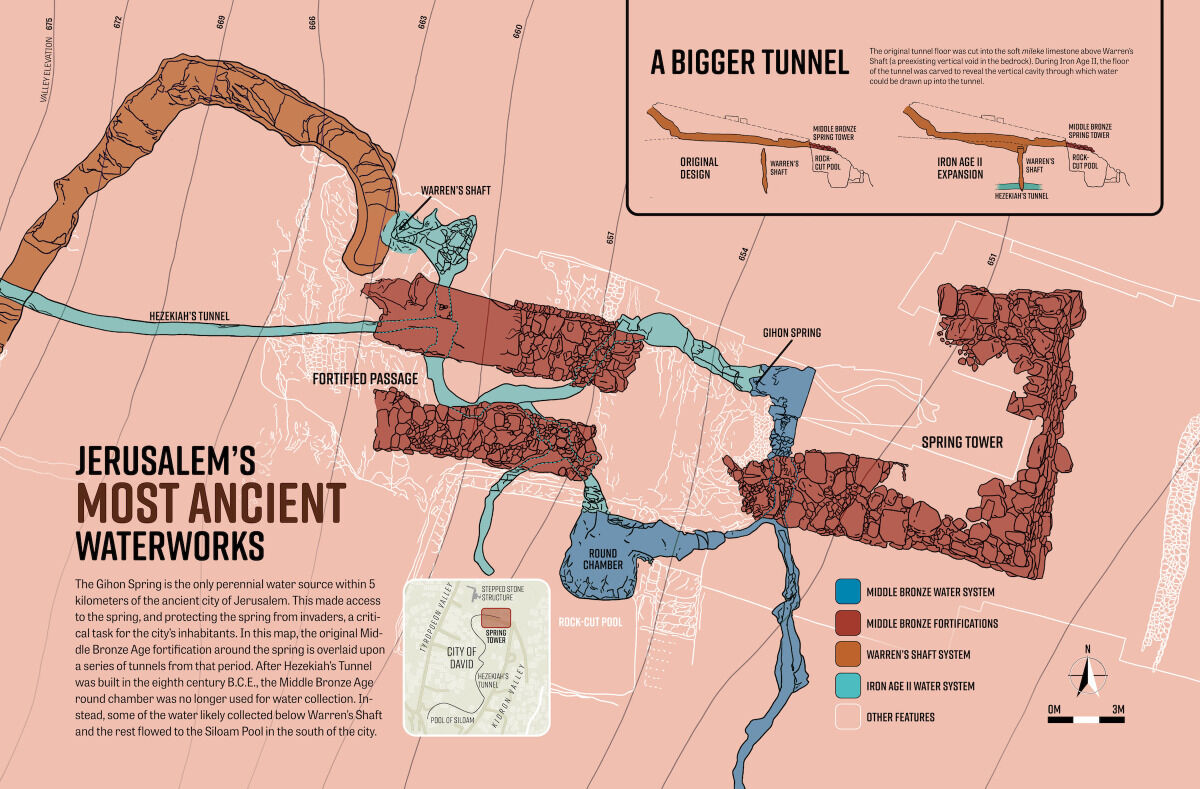

The identity of Melchizedek is an intriguing separate study. Clearly, his significance in establishing the city of Jerusalem cannot be underestimated. Rabbi Jehiel Heilprin’s Seder HaDoroth, published in 1769, boldly asserted that Melchizedek was the first to complete a wall around Jerusalem. And rather remarkably, some two centuries later, such a thing was (partially) uncovered by archaeologists Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron. They discovered the earliest fortification structure of Jerusalem (the Spring Citadel), centered around the symbolically significant Gihon Spring, dated to the 19th century b.c.e.—matching precisely the period of Genesis 14, in which Melchizedek and Abraham were on the scene. (Read “Archaeology Reveals Jerusalem’s Origins” for more information.)

Certainly, opinions will continue to differ as to the exact identity of Melchizedek. But what is certain is the religious significance of the city attributed to him, as representative and “priest of the most high God.” Jerusalem was an ancient city not known for its impressive size or any other such comparative physical features, but rather, one in which its true significance is tied to a religious background (as it continues to be to this day).

As such, perhaps it should come as no surprise for our pharaoh to seek to “place his name in Jerusalem forever,” nor for a native king of the city to employ such language in his letter to the ruler. After all, following biblical chronology, these leaders would only have been recognizing a sanctity inherent to the city that was then already 500 years old.

The question, however, is this: Whose name continues to be “placed in Jerusalem forever”? Whose divine name, across these thousands of years to our present day, continues to be regularly associated with this “center of the world,” the city “closest to heaven”?

It’s certainly not that of Pharaoh Akhenaten.