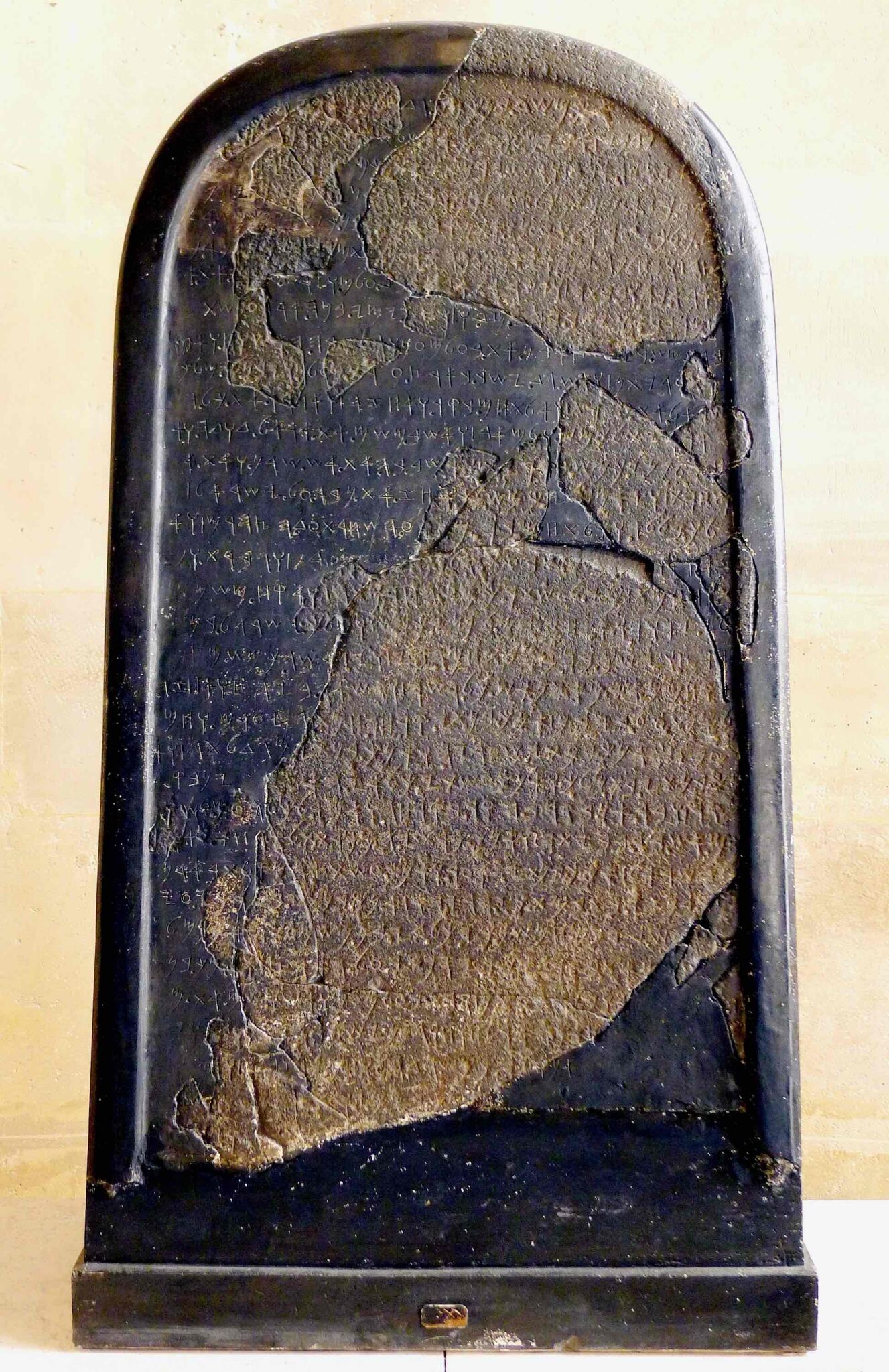

“[T]he most important discovery ever made in the field of Oriental epigraphy!”

So proclaimed Ernest Renan, French expert of Semitic languages and civilizations. He was speaking about the Mesha Stele (also known as the Moabite Stone). This 3-foot-tall basalt stone holds 34 lines of Phoenician script, or paleo-Hebrew, recording the victories of the Moabite King Mesha. Here are a few excerpts from the text:

I am Mesha, son of Chemosh(-yatti), king of Moab, the Dibonite. … I have built this sanctuary for Chemosh … for he saved me from all aggressors, and made me look upon all mine enemies with contempt. Omri was king of Israel, and oppressed Moab during many days, and Chemosh was angry with his aggressions. His son succeeded him, and he also said, I will oppress Moab …. Now Omri took the land of Madeba, and occupied it in his day, and in the days of his son, 40 years. And Chemosh had mercy on it in my time …. And the men of Gad dwelled in the country of Ataroth from ancient times, and the king of Israel fortified Ataroth. …

And Chemosh said to me, Go take Nebo against Israel, and I went in the night and I fought against it from the break of day till noon, and I took it: and I killed in all 7,000 men, but I did not kill the women and maidens, for I devoted them to Ashtar-Chemosh; and I took from it the vessels of yhwh, and offered them before Chemosh ….

Rumors about the stele being in the possession of local Bedouin people reached French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau in 1868. Since it was not safe to travel freely through the country, Clermont-Ganneau sent Arab intermediaries in 1869 to make a schematic copy and a stamp impression, both of which confirmed the importance of the stele. In the following years, the stele was broken and distributed between the tribes—then, piece by piece, it was put on the antiquities market in Jerusalem. Clermont-Ganneau acquired two of the largest pieces and other fragments; other institutions added to it throughout the years. Because of Clermont-Ganneau’s representations of the complete stele, experts were able to piece together the fragments and fill in the gaps.

Once interpreted, the stele became the main secular source of history for the Moabite people. And it becomes biblically momentous when placed next to the Bible.

Some of the most significant references backing up biblical text are King Mesha’s record of his rebellion against his Israelite overlords. He names specifically the Israelite King Omri (2 Kings 1, 3-4); the Israelite God yhwh, the earliest absolute reference to Him; the tribe of Gad, dwelling in ancient Moabite territory (Joshua 13); and he confirms Chemosh as the main god of the Moabite people.

Probably the most important reference, however, is King Mesha’s reference to the house of David.

In 1994, French scholar André Lemaire was studying the stele and reconstructed the 31st line which reads,

“[to herd] the small cattle of the land, and Horonain, in it dwelt house of [D]VD…”

King Mesha boasts of capturing territory belonging to the “house of [D]VD,” placing his herds there to graze. Though one letter of DVD is not complete, Lemaire stated that any other reading than David would be an awkward fit. This makes the stele one of three specific archaeological references to the biblical King David!