Chances are you don’t know too much about King Jotham. He’s one of those biblical characters that requires a reread of the Bible as a refresher—he’s certainly no David, Samson or Moses.

Jotham is described as a “mighty” king, but whose righteous 16-year reign is somewhat overshadowed by his incapacitated leprous father, for whom he served a significant period of time as co-regent. Archaeologically, this king has likewise been one of the most enigmatic of all eighth-century b.c.e. biblical kings.

Nearly all other biblical leaders from this century have had their names confirmed through archaeological discovery: These include Jotham’s father, Uzziah; son Ahaz; and grandson Hezekiah—as well as eighth-century Israelite kings Jehoash, Jeroboam ii, Menahem, Pekah and Hoshea; Egyptian pharaohs So and Tirhakah; Syrian kings Hazael, Ben-Hadad and Rezin; Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser, Shalmaneser, Sargon and Sennacherib; and Babylonian king Merodach-Baladan.

What, if any, evidence is there of Jotham?

Seal in Edom? Or Edomite Seal?

Some 80 years ago, during archaeological excavations of an ancient copper smelting site at Tell el-Kheleifeh (near modern-day Eilat), Nelson Glueck’s team discovered a beautiful, ornate seal still contained within its copper signet ring. The ring had a simple inscription reading:

“Belonging to Jotham”

In 1961, famed Israeli archaeologist Nahman Avigad published a brief study on the discovery, postulating that the seal’s Jotham could have been the famous Judahite king.

The seal was dated to the eighth century b.c.e.—the time frame of the biblical King Jotham. And seals like these were reserved for high officials. But did anything more link the seal to this royal individual? After all, no title was given—unusual, if it indeed belonged to the king.

It was speculated that this seal could have belonged to Jotham during his days as co-regent, with the ranking title “over the king’s house” (2 Chronicles 26:16-20)—perhaps relating to administration of this same southern area that Uzziah was credited with rebuilding (2 Kings 14:22). Prof. Nahman Avigad wrote, “One may suppose, then, that it was in the capacity of a minister and not as king that Jotham used the signet ring.”

Wait a Second …

It all checked out … until a reassessment revealed it to have been dated in error. Instead of the middle-eighth century b.c.e.—synonymous with the biblical Jotham—the seal was re-dated to the early-to-middle seventh century b.c.e., too late for any overlap with the biblical ruler.

The seal was further determined to be Edomite in nature. In 1978, closer palaeographic examination of the writing revealed that it matched specifically Edomite form, and that of the seventh century b.c.e. (This knowledge was not available decades earlier at the time of the first identification of the seal. This was still early on in the days of seal and bullae discovery and research.) This new, seventh-century Edomite appraisal checked out against the scrutiny of other experts.

Actually, this identification still fits well alongside the biblical account: During the reign of Jotham’s son Ahaz, the Edomites reclaimed the territory of Eilat and continued to rule it into and throughout the seventh century b.c.e.

Jotham’s existence remained unconfirmed, unlike the other eighth-century biblical kings, several of which had long been discovered on Assyrian inscriptions. No great surprise, though—after all, the Bible states that Jotham reigned only 16 years, compared with his father’s 52-, grandson’s 29- and great-grandson’s 55-year reigns.

But There’s More

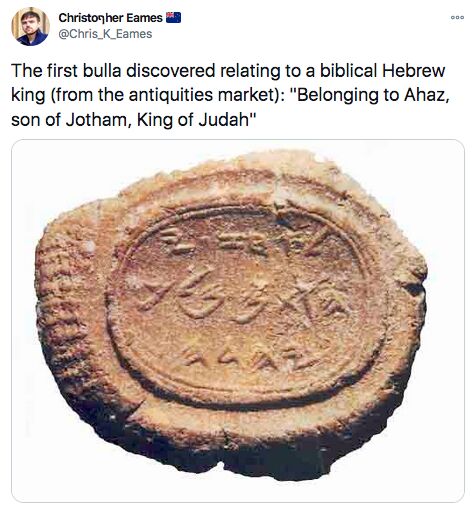

In 1996, amid a certain degree of fanfare, the first bulla (clay seal impression) belonging to a king of Israel or Judah came to light: the Ahaz seal. This bulla was purchased from the antiquities market by world-renowned collector Shlomo Moussaieff. The seal bears the inscription:

“Belonging to Ahaz, (son of) Jehotham, King of Judah.”

This seal uses a longer “theophoric” version of Jotham’s name, Jehotham. Both represent the same name—the Bible using the shorter form. (Name forms like this are not uncommon—even Ahaz himself is named on an Assyrian inscription as Jehoahaz, with the divine “Jah” element.)

Even though the Ahaz seal was bought on the antiquities market (rather than excavated in a controlled scientific excavation), there is general consensus that it is authentic. Bullae are almost impossible to accurately forge: Script is extremely period-specific, petrographic analysis can identify where the clay was sourced, and ancient artifacts such as these develop a patina over the course of thousands of years (to name a few “checks and balances”). As such, even antiquities market items can be “proved” authentic (such as was the case recently, with the Jeroboam ii seal). And since its discovery, the seal fits well alongside the later “Hezekiah, son of Ahaz” bulla, which was found on an excavation.

Since the Ahaz seal was the first seal of a biblical king, there was excitement surrounding its discovery and its connection to King Ahaz. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the secondary figure named on the bulla received less attention, yet was no less validated: King Jotham.

Here, finally, was our King Jotham.

Still, the 1996 find wasn’t the last “seal-stamped” word on King Jotham—more on that further down.

King of the Ophel

Who, then, was King Jotham? As with the archaeological remains, there is little in the Bible about his reign. We learn that he was a righteous king over an unrighteous people. 2 Chronicles 27:2 states:

And he did that which was right in the eyes of the Lord, according to all that his father Uzziah had done …. And the people did yet corruptly.

One of the most interesting details about this king is that he is commended for his building efforts on the Ophel (interesting to me, at least, since I’ve assisted on excavations on Jerusalem’s Ophel—a site just between the Temple Mount and the City of David). Verse 3 in the New King James Version:

He built the Upper Gate of the house of the Lord, and he built extensively on the wall of Ophel.

This statement is of note in light of our excavations along the Ophel wall, with construction material discovered related to this middle-Iron iib period (much of which can be found in excavation director Dr. Eilat Mazar’s comprehensive excavation publications). It is difficult to know for certain which king built what (after all, Jotham’s great-grandson Manasseh also heavily developed the Ophel—2 Chronicles 33:14). During our 2013 Ophel excavation, aiba office manager Brent Nagtegaal, Area B supervisor, personally took charge of excavating an extremely confusing, confined section of the site. It turned out to be a series of successive, collapsed Iron iib floor layers. It’s uncertain what caused the collapse—perhaps an earthquake. Nonetheless, the layers indicated successive building projects on the Ophel during the mid-to-late-Iron iib period, something that would fit well with the biblical account of the successive eighth–seventh-century b.c.e. constructions of Jotham and Manasseh.

Before we leave Dr. Mazar’s excavations, mention must be made of another bulla discovered just south of the Ophel in her earlier excavations of the City of David. This one takes us full-circle—potentially back to Jotham’s days of co-regency.

A complete Iron iib bulla was unearthed with the inscription “Belonging to Jotham, Servant of the King.” The Hebrew word for servant, eved, does not have strictly the same connotation as the English word; on an official seal such as this one, it denotes a high-ranking officer. Jeroboam bore this title as “ruler” under Solomon, before he was made king of Israel (1 Kings 11:26-28). The captain-cum-king Zimri bore this title (1 Kings 16:9). King Ahaz described himself with this title to the king of Assyria (2 Kings 16:7). Nebuchadnezzar’s captain Nebuzaradan bore this title (2 Kings 25:8).

At the end of her detailed analysis of this bulla, Dr. Mazar concluded with the following in The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008, Final Reports Vol. i:

Because this title [eved hamelekh] can indicate an array of high clerical functions for the king, it possibly refers here to ytm [Jotham] the son of King Uzziah who was regent when his father was sick with leprosy: “And Jotham the king’s son was over the house, judging the people of the land” (2 Kings 15:5).

Jotham’s Legacy

Beyond Jerusalem itself, Jotham’s building works took place throughout the land. “Moreover he built cities in the hill-country of Judah, and in the forest he built castles and towers” (2 Chronicles 27:4).

Material relating to this period has been found at numerous sites around Judah. Based on Sennacherib’s inscriptions describing his attacks against Hezekiah at the end of that century, Judah apparently had accumulated many fortified strongholds—46 “strong walled cities” and towns “which were without number.”

Jotham was also successful in warfare against the Ammonites (verse 5). This war is possibly connected to the account in Amos 1:13, which describes the Ammonites “ripp[ing] up the women with child of Gilead.” Assyrian records attest to a certain King Shanib as ruler of the Ammonites around this time. (About 10 years ago, a massive Ammonite statue of Shanib’s grandson, Yarh-Azar, was discovered—see right.) Jotham subdued the nation and turned them to tribute (2 Chronicles 27:6):

So Jotham became mighty, because he ordered his ways before the Lord his God.

Although a brief biblical account, it’s a favorable assessment.

In Summary

The “Jotham seals” journey is a fascinating snapshot of not only the middle-late period of the Judahite kings but also archaeological discovery as it was during the 20th century—with assessments and reassessments, excavated and antiquities market items. It gives a glimpse of archaeology before the advent of wet sifting, which method has led to the discovery of thousands of bullae (such as Mazar’s Jotham bulla) just in the past couple of decades. Bullae of numerous other biblical figures have been discovered using this method, including that of King Hezekiah, Isaiah, the prince Gedaliah, “eunuch” Nathan-Melech, perhaps even King Zedekiah’s son, etc.

This journey of discovery, especially related to the very smallest archaeological “stones” of history, the seals, is summed up well in Psalm 102:14-15:

Thou wilt arise, and have compassion upon Zion; For it is time to be gracious unto her, for the appointed time is come. For Thy servants take pleasure in her stones, And love her dust.