The biblical king Ahaz of Judah is well attested to in archaeology. He is recorded as giving tribute to the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser iii, in his eighth-century b.c.e. cuneiform Summary Inscription vii—paralleling the biblical account in 2 Kings 16. And he is mentioned on the seals of his son, Hezekiah.

The existence of King Hezekiah was corroborated by the 2015 discovery of the Hezekiah bulla—the first and only confirmed seal stamp ever found belonging to a king of Israel or Judah in a controlled, scientific excavation.

But that was in a controlled excavation. Other seals have emerged on the antiquities market, where ancient items of unknown provenance have long been bought and sold. These items, unfortunately, retain some doubt as to their authenticity, due to their lack of provenance—but still, bullae and seal stamps are virtually impossible to forge.

And so, including discoveries from the antiquities market, what was the first-discovered seal attesting to a Hebrew king? It was the father of Hezekiah: the evil king Ahaz.

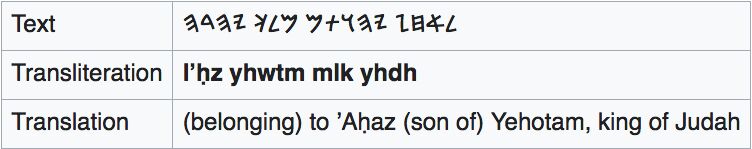

Epigraphist Robert Deutsch revealed the discovery, which was purchased in 1996 by the late famous collector Shlomo Mousaieff. The bulla contains three lines of text, reading, “Belonging to Ahaz, son of Yehotham, King of Judah.”

The inscription is clear, denoting the late eighth-century b.c.e. King Ahaz and his father Jotham (inscribed on the bulla with the longer theophoric Yeho version of the name).

There is general consensus that this item is authentic. Again, bullae are almost impossible to accurately forge. Script is extremely period-specific, petrographic analysis can identify where the clay was sourced, and ancient artifacts such as these develop a patina over the course of thousands of years—to name a few “checks and balances.”

The Ahaz bulla is beautifully preserved and complete, and while it lacks any motifs, the script is expertly engraved. The bulla had been used to seal a papyrus scroll, evident from the imprint on the reverse. And the apparent pattern of a thumbprint on the left-hand side of the bulla may indicate that the king was right-handed—using his right hand to stamp the clay.

Given the other discoveries of King Ahaz, this seal is not “necessary” to prove his existence. Still, it gives a special insight into the personal seal of the king. More significantly, it constitutes the first evidence of his father, King Jotham.

Another seal attesting to King Ahaz is the “Ushna seal.” This is a red semiprecious stone seal likewise discovered on the antiquities market, with the inscription “Belonging to Ushna, Servant of Ahaz.” The seal, dated to the late seventh century b.c.e., evidently belonged to one of the king’s servants. This seal is more ornate, depicting pagan Egyptian imagery. While the king’s personal seal stamp does not contain any motifs (indeed, it is quite small even for a seal, and contained a significant amount of text), Deutsch believes the original seal itself would have been richly decorated.

A growing body of evidence has been discovered relating to this evil king, whose 16-year reign was couched between the righteous rule of his father Jotham and his son Hezekiah. The Bible describes Ahaz sacrificing one of his sons, hiring the king of Assyria to destroy the northern kingdom of Israel, desecrating the temple, and removing the incense altar outdoors for “personal use” (2 Kings 16).

In fact, there is a heavy emphasis during Ahaz’s reign on burning incense. He made sure that each and every city of Judah was outfitted with incense altars to worship with. “And in every single city of Judah he made high places to burn incense to other gods” (2 Chronicles 28:25; New King James Version). A recent, remarkable discovery of cannabis burned at a Judahite high place, dating to this period, points to the type of “incense” worship Ahaz endorsed.

The discovery of King Ahaz’s bulla, used to seal royal correspondence during this time period, adds to the burgeoning trove of exciting evidence for the biblical figures and wider biblical account. As Deutsch concluded his 1998 official English publication of the bulla for Biblical Archaeology Review:

This modest lump of clay thus has much to teach us—in addition to providing the thrill that comes from such a direct connection to an ancient king of Judah.