Archaeological evidence of biblical personalities abounds. Kings, pharaohs, princes, government officials, military officers and priests have all been attested to in the archaeological record. But there is another, especially intriguing, group of biblical figures: the prophets. Their sayings and writings, preserved in the Bible, are a claim of miraculous, supernatural inspiration. Of course, many scoff at their prophecies. Regardless of differing opinions, the question should be asked: Has any evidence been found of the prophets? Can anything be said of their historicity from the archaeological record?

Unlike the officials described above, prophets are difficult to demonstrate through archaeology. They usually did not hold governmental offices and thus would not have had much of the regalia, stamps and correspondence preserved. They did not build cities. More often than not, Israel’s prophets were hated by those in power—the authorities were more than willing to be rid of any evidence of them. Many (if not most) of the prophets were simply of humble occupations. Yet their preserved biblical texts live on as some of the most precious writings that we have.

Let’s examine the evidence that has emerged for a number of the biblical prophets. We’ll list them in the order that they appear in the biblical account.

Balaam

The prophet Balaam was one of ancient Israel’s great archenemies, and a pagan mystic. According to the biblical account in Numbers 22-24, the Moabite King Balak hired Balaam the son of Beor to curse the 12 tribes of Israel, which were coming dangerously close to the land of Moab on their way to the Promised Land.

King Balak offered a rich reward to Balaam for pronouncing a curse upon the Israelites—a reward Balaam deeply craved. Yet despite Balak’s wishes, God put it in Balaam’s mind to only prophesy blessings of the encamped Israelites, greatly frustrating the king of Moab. Finally, out of desperation to receive Balak’s rich reward (yet knowing he could not openly contravene God’s instructions), Balaam advised that Moabite and Midianite women lead the Israelite men astray. The devious scheme resulted in a plague on Israel that led to the deaths of 24,000. Balaam was later killed when the conquering Israelites attacked the Midianites (Numbers 31:8).

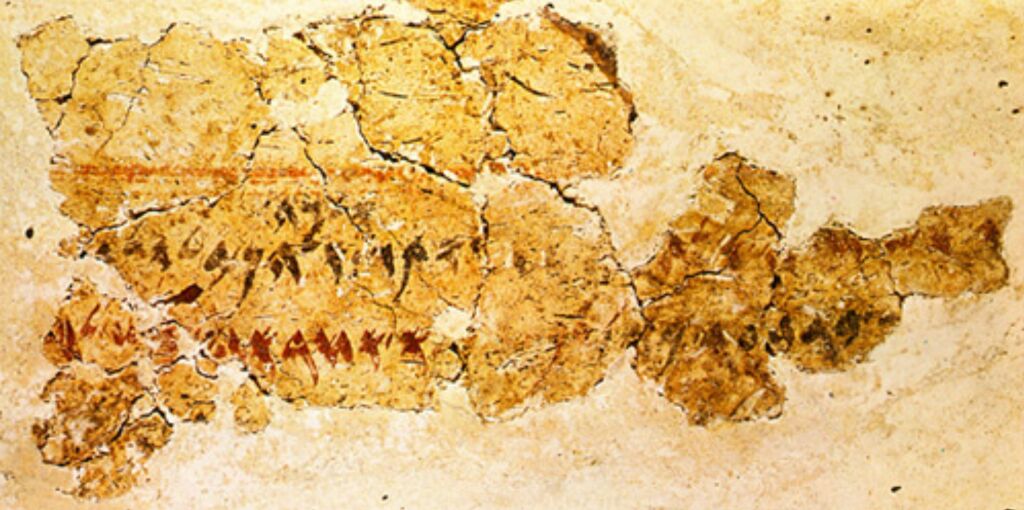

Deir Alla, a Jordanian town, lies about eight kilometers east of the Jordan River. In 1967, within the walls of an ancient settlement site, Dutch excavators discovered a painted script, written in a form of Aramaic–Canaanite language, dating to around 800 b.c.e. The incomplete, somewhat lengthy script has been deciphered, and it begins with the following dramatic introduction:

The misfortunes of the Book of Balaam, son of Beor. A divine seer was he. The gods came to him at night ….

The long script proceeds to describe a vision Balaam witnessed of imminent destruction by the gods. The text repeatedly mentions the name “Balaam, son of Beor,” as well as various gods including Shagar and Ishtar. The names “El” and “Shaddai” are also mentioned (akin to the Hebrew words used for God).

The ancient wall script gives some interesting insight into Balaam. Not only did he play a role large enough to be featured in the biblical Israelite history, he must have also been well known within the general territory of Jordan in order for his tradition to continue and to receive veneration on a wall-piece regarding his visions. The inscription’s indication of his stature matches with the biblical implication that Balaam was a renowned seer—one famous enough for the king of Moab to personally and repeatedly seek out. The biblical account puts Balaam on the scene c. 1400 b.c.e. This inscription shows that in the following centuries (up to the eighth century b.c.e.) a “Book of Balaam” had been compiled, venerating this man.

Also discovered at Deir Alla is a series of small, inscribed clay tablets, one of which states: “… they are the smiters of Pethor.” Pethor was where Balaam lived (Numbers 22:5). These tablets are roughly dated to at least 1200 b.c.e. or earlier.

Elisha

Elisha was an important prophet for the northern kingdom of Israel. His life, prophecies and miracles performed through him are described in 1 Kings 19, 2 Kings 2-9 and 2 Kings 13.

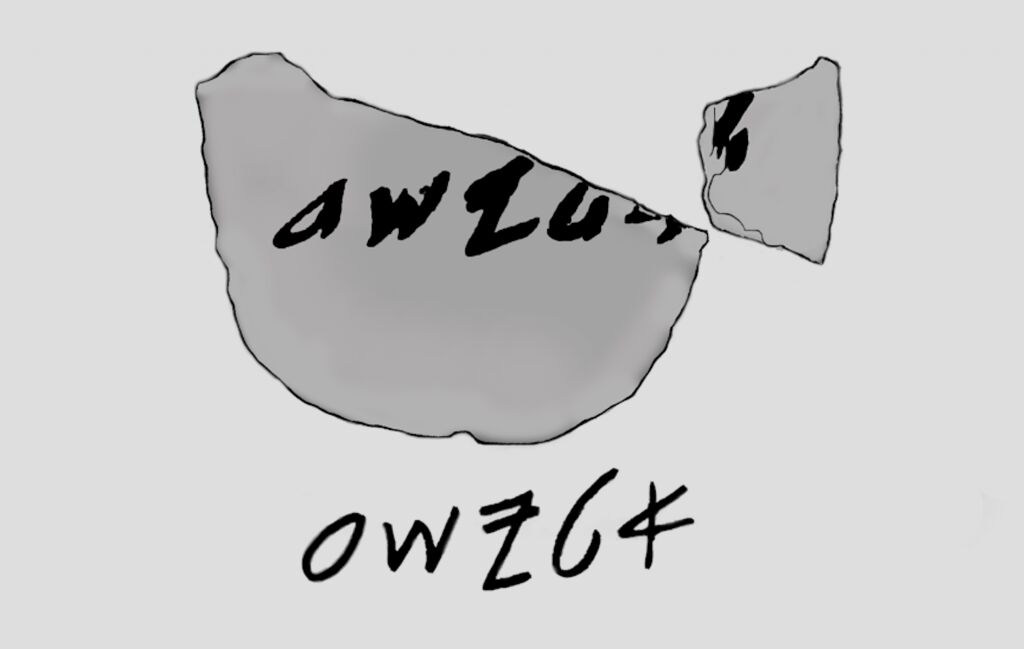

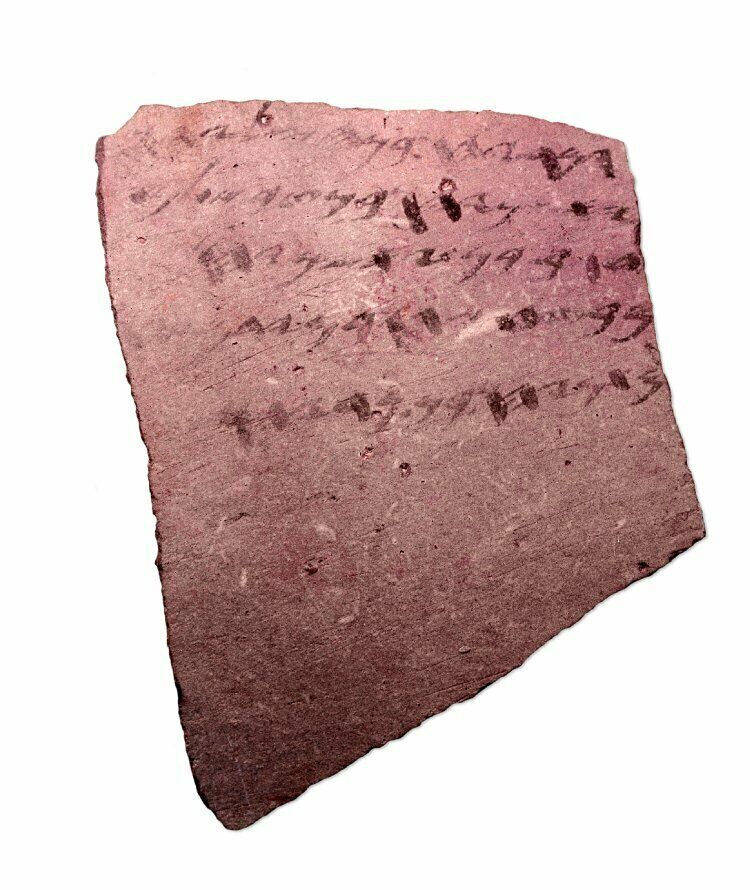

In 2013, during excavations led by Prof. Amihai Mazar at Tel Rehov, a unique artifact caught the attention of the excavators. A shard of pottery was discovered with ancient text written on it in red ink. The shard, along with the layer within which it was found, was dated to the middle-ninth century b.c.e. The ancient Hebrew script was damaged, yet still could be translated with virtually complete certainty as the name “Elisha.” See below:

Unearthing a single name is nowhere near sufficient evidence for proving a biblical individual. But this potsherd is interesting for a number of reasons. Not only does the name parallel the biblical prophet, it also dates to the same time period that he lived. And it was found in an area where he spent much of his time (he was born only seven miles away, in a town named Abel-Meholah). The Bible states that Elisha spent so much time in this area, that a couple living in nearby Shunem were inspired to make a chamber in their house for him to stay in (2 Kings 4).

Additionally, an inscription bearing the name “Nimshi” was found nearby (as well as a second “Nimshi” inscription five miles away). Elisha told one of his disciples to go and anoint as king a man named Jehu, specifically telling him that Jehu was a descendant of Nimshi (2 Kings 9:1-3). So this name had significance to Elisha’s record.

Added to this ancillary evidence is the simple fact that, based on current knowledge, the name “Elisha” was quite rare in ancient Israel—thus, the chances of this being the prophet are even higher.

The ancient house itself, within which the Elisha ostracon was found, was unique. It had a slightly unusual design: It was divided into two wings, with two entrances from the street (as opposed to one entrance and one central room). It was thus a more publicly accessible building. Furthermore, large vessels were found, larger than would be expected for family use. It seems that this building served as a communal area—maybe as a gathering place for Elisha’s disciples, one of his “schools of the prophets.” Even the way the name was written, centered and alone on the partially-rounded ostracon, gives a sense of something special about this particular individual.

Of course, we don’t yet have enough proof to say outright that this inked “Elisha” referred to the prophet. However, the sheer weight of evidence is compelling and shows that it most likely does refer to the man.

Isaiah

Isaiah is one of the most famous of the biblical prophets. After all, he has an entire book written by him (said to be a “miniature Bible” in itself). Having served within the Jerusalemite courts (probably in or around the royal Ophel), Isaiah is well known for his close partnership with Judah’s King Hezekiah.

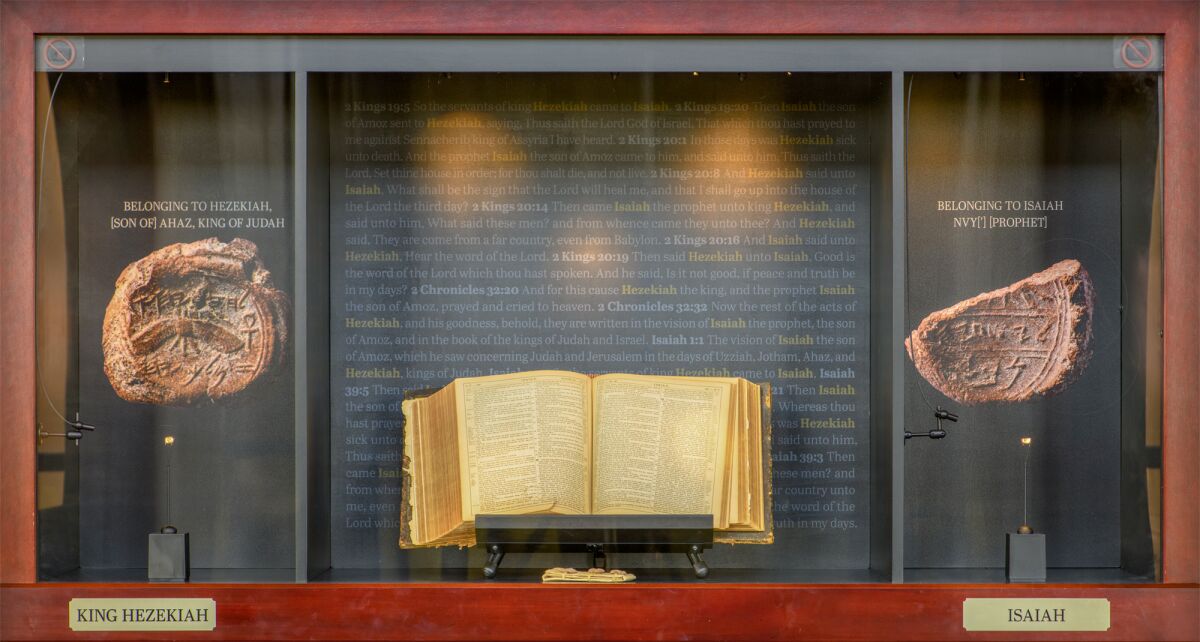

During her 2009–10 Jerusalem Ophel excavations, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar and her team unearthed a bulla (a clay stamp seal) belonging to King Hezekiah. The find was staggering—the first seal impression of a Hebrew king ever found in archaeological excavation. And mere meters away, in the same strata—dating to the early sixth century b.c.e.—another exciting bulla was found. This one carried the impression L’Yeshaiahu [?] Navi[?]. This is translated as Belonging to Isaiah [the] Prophet.

It was a thrilling discovery that made headlines around the world. However, some degree of debate has raged as to whether or not this bulla really did belong to Isaiah the prophet. While this identification is by far the best fit, some have argued that the bulla may have belonged to someone else due to the final word “prophet” having been damaged at the end. (Only Navi is preserved, not the full word for prophet, Navi’. The bulla is damaged where this final letter would be expected. However, a close reexamination of the bulla appears to show this final, damaged letter after all. This, and other evidence, helps to prove that the seal impression really did belong to the Prophet Isaiah. For more detail on this, see here.)

The Isaiah bulla is particularly special because of its proximity to the bulla of his close biblical compatriot, King Hezekiah. Further, the discovery has a special place in our hearts here at aiba—it was excavated by one of our own staff members (albeit at the time, unwittingly) during our support for Dr. Eilat Mazar’s 2009–2010 Ophel excavations.

The organization behind aiba has been loaned both the Isaiah and Hezekiah bullae, which are on display in our premiere exhibit in Edmond, Oklahoma. You can view the online exhibit, “Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered,” here; or if you are in the area and would like to visit the exhibit in person, visitor details are here (the exhibit is free). If you’d like a free full-color brochure of the exhibit, simply request it be mailed to you or download it here.

Jeremiah and Urijah

Jeremiah was the last major prophet on the scene before the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians. He too has a biblical book in his name. Jeremiah was deeply unpopular among the ruling classes for prophesying the fall of Jerusalem and warning the Jews to surrender in order to be spared. He was physically abused on several occasions and repeatedly thrown into prison. Two royal princes in particular plotted to kill him—Jehucal son of Shelemiah and Gedeliah son of Pashur (Jeremiah 38:1). Incredibly, two clay seals belonging to these princes have been found. Like the Isaiah and Hezekiah bullae, they were discovered by Dr. Eilat Mazar’s team, and they were found right around the same structure. You can read more about them here, or see our online exhibit page here (as with the Isaiah and Hezekiah bullae, we also hosted the premiere exhibit of the Jehucal and Gedaliah bullae).

Another bulla—the seal of the righteous scribe Gemariah, who also features in the book of Jeremiah—was found decades earlier around the same location during excavations led by Prof. Yigal Shiloh. You can read more about that bulla here.

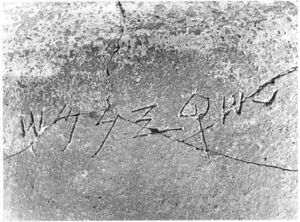

During the period just before the Babylonian captivity, there were two other prophets on the scene—the false prophets Urijah and Hananiah. As yet, there have been no discoveries bearing certain reference to Jeremiah or Urijah (Hananiah somewhat, but we’ll cover him further down). However, a couple of “letters”—broken potsherds, called ostraca—bear near-certain reference to at least one or more of these prophets. These are the Lachish Letters. They are part of a collection of dozens of clay pottery shards covered in ink writing. Nearly all of them date to the time just before the fall of Jerusalem, c. 586 b.c.e. The urgent correspondence they contain provides a unique snapshot into a time of sheer desperation for the nation of Judah.

The shards contain numerous names and references, including the names Jeremiah and Neriah—it is uncertain, though, as to whether or not these refer to Jeremiah the prophet, or to his scribe Baruch’s father, Neriah. There is also a Zedek[…?], a possible damaged reference to King Zedekiah.

One of the shards, Letter iii, states the following:

The commander of the army, Coniah, son of Elnathan, has gone down to go to Egypt …. And as for the letter of Tobiah, the servant of the king, which came to Shallum, son of Yada from the prophet, saying ‘Beware!’—your servant has sent it to my lord.

Here we find evidence, among apparent military correspondence, of a prophet’s warning. Jeremiah had been instructing the Jews not to resist the Babylonians militarily. It is very possible that this letter is a reference to Jeremiah’s warning. It also may refer to Urijah’s warning, as he was likewise proclaiming a message of surrender. Urijah, though, had not been ordained by God, and though his message bore similarities to Jeremiah’s, he was a false prophet. This is what the Bible states happened to him (Jeremiah 26:20-23):

… Urijah … prophesied against this city and against this land according to all the words of Jeremiah: and when Jehoiakim the king, with all his mighty men, and all the princes, heard his words, the king sought to put him to death; but when Uriah heard it, he was afraid, and fled, and went into Egypt; and Jehoiakim the king sent men into Egypt, Elnathan the son of Achbor, and certain men with him, into Egypt; and they fetched forth Uriah out of Egypt, and brought him unto Jehoiakim the king; who slew him with the sword ….

There are a number of parallels between Letter iii and this biblical account. Both reference a prophet with a warning message. Both describe a military incursion into Egypt, with an association to a man named Elnathan. Could this have been the expedition to seize Urijah for his message of warning? It is possible that the letter’s Coniah, son of Elnathan, was joined by his father in the expedition (as per the biblical account of Elnathan himself going into Egypt). All told, this Lachish letter may well describe the very same biblical account.

Another notable piece, Letter xvi, is generally translated as the following:

your servant sent it … the letter of sons of [?] … [?]ah, the prophet.

There is some dissent about the translation of the word “prophet.” However, the above constitutes the widely accepted reading. In this case, only the last Hebrew letter of the prophet’s name survived, “-ah.” This could potentially refer either to Jeremiah or one of the false prophets, Urijah or Hananiah. We cannot be sure which one, but considering his high status and role in Judah, it may well be Jeremiah.

Hananiah

The false prophet Hananiah son of Azur is briefly referenced in the book of Jeremiah. Jeremiah 28 describes Hananiah proclaiming that Judah would be saved from the Babylonians, and that in two years King Jehoiakim would be reinstated and the temple treasures returned. He also physically accosted Jeremiah, who was present for Hananiah’s proclamation and warning the public to wait and see what would come of Hananiah’s predictions.

We mention Hananiah separately because of a small blue stone seal that has been discovered, bearing the words “Belonging to Hananiah, son of Azariah.” Azur, the name of the biblical father of Hananiah, is a short form of the name Azariah. This seal dates to the correct time period for the biblical prophet Hananiah. However, Hananiah and Azariah would have been quite common names, so it is not yet certain whether this was the man mentioned in Jeremiah 28. A further identifying factor—such as the title of prophet, or a town of citizenship (Hananiah was from Gibeon)—would make the answer clear. Still, the fact that both father and son are listed, as well as a parallel dating, means that there is a good chance the seal belonged to the false prophet.

And the Prophecies?

While the prophets are naturally going to be a very difficult class to discover archaeologically (as described above), much has been uncovered already, providing evidence for their existence. We’ve only generally covered individuals alluded to by name—but when considering the broader context of their lives, prophecies and biblical books, much more has been proved.

You can read about the plethora of discoveries proving the accuracy of the book of Jeremiah here and about Elisha’s life here. There’s evidence supporting the biblical account of Moses, the book of Daniel and the already proved King David. Many of the psalms are prophetic (and David is directly named as a prophet in the New Testament—Acts 2:29-30). The list goes on.

And of course, the greatest “remains” we have are the preserved Holy Scriptures. After all, much more important than the people themselves is what they said. (And many of their prophecies actually pertain to the “end time”—terrifying events that coincide eerily with our modern, widespread proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Those paralyzing prophecies are concluded, finally, with the coming of the Messiah and, eventually, world peace.) Prophecy, if it is to be proved real, can only be the result of supernatural power. So were the biblical prophets frauds? As is so often claimed, were their “too accurate” prophecies of ancient events—such as those predicted in the Book of Daniel—only written long after the events themselves had occurred?

You can read more about evidence relating to the early authenticity of the biblical prophets’ writings in our articles here and here.