The biblical prophet Balaam was one of ancient Israel’s great archenemies. According to the biblical account in Numbers 22-24, the Moabite King Balak hired Balaam the son of Beor to curse the Twelve Tribes of Israel, which were coming dangerously close to the land of Moab on their way to the Promised Land.

King Balak offered a rich reward to Balaam for pronouncing a curse upon the Israelites—a reward Balaam deeply lusted after. Yet despite Balak’s wishes, God put it in Balaam’s mind to only bless the encamped Israelites, frustrating the king of Moab to no end. Finally, out of desperation to receive Balak’s rich reward (yet knowing he could not openly contravene God’s instructions), Balaam advised that Moabite and Midianite women lead the Israelite men astray. The devious scheme resulted in a plague on Israel that led to the deaths of 24,000. Balaam was later killed when the conquering Israelites attacked the Midianites (Numbers 31:8).

Amazingly, the prophet Balaam is found not only in the Bible, but also in archaeological evidence unearthed at Deir Alla.

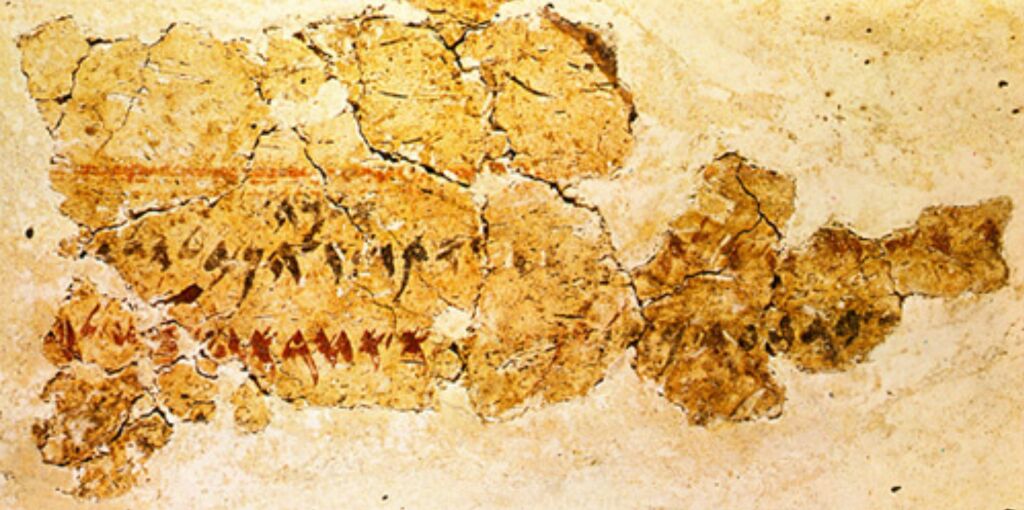

The Deir Alla Inscription

Deir Alla is a Jordanian town about 8 kilometers east of the Jordan River. In 1967, within the walls of its ancient settlement site, Dutch excavators discovered a painted script, written in a form of Aramaic/Canaanite language, dating to around 800 b.c.e. The incomplete, somewhat-lengthy script has been deciphered, beginning with the following dramatic introduction:

The misfortunes of the Book of Balaam, son of Beor. A divine seer was he. The gods came to him at night …

The long script proceeds to describe a vision Balaam witnessed of imminent destruction by the gods. The text repeatedly mentions the name “Balaam, son of Beor,” as well as various gods including Shagar and Ishtar. The names “El” and “Shaddai” are also mentioned (akin to the Hebrew words used for God).

The ancient wall script gives some interesting insight into Balaam. Not only did he play a role large enough to be featured in the biblical Israelite history—he must have also been well-known within the general territory of Jordan, in order for tradition to continue and even be venerated on a wall-piece regarding his visions. The inscription’s indication of his stature matches with the biblical implication that Balaam was a renowned seer—one quite famous in order for the king of Moab to personally seek out his repeat assistance.

The Deir Alla discovery was the first inscription to identify an Old Testament prophet. The find also joins a series of small, inscribed clay tablets discovered at Deir Alla three years earlier, on one of which was written the following: “… they are the smiters of Pethor.” Pethor was where Balaam lived (Numbers 22:5). These tablets are roughly dated to at least 1200 b.c.e. or earlier (the Bible’s account of Balaam would have occurred around 1400 b.c.e.).

Yet for all the fascinating parallels with the biblical figure, some claim that the Deir Alla Balaam inscription contradicts the Balaam of the Bible.

Prophet of God? Or False Prophet?

In his book Problems of Genre and Historicity with Palestine’s Inscriptions, the minimalistic biblical scholar and theologian Thomas L. Thompson writes:

Both stories [Deir Alla and the Bible] have Balaam speak with the voice of God. This determines the fate and destiny of nations. In the Bible’s story, he is a prophet of Yahweh. In the Deir Alla text, he is associated with a god bearing the name Shgr, “Shaddai” gods and goddesses, and with the goddess Ashtar …

Thompson states that both accounts, contradictory in nature, are fictional and merely demonstrate ancient storytelling techniques. Similarly, Dr. J Day comments in The Daniel of Ugarit and Ezekiel and the Hero of the Book of Daniel:

… one might cite the example of Balaam, whom the dominant strand of Old Testament tradition regards as a true prophet (Num. xxii-xxiv), but who is revealed by a recently discovered Aramaic text from Deir Alla to have been a polytheist.

The above statements, among others, assume that the biblical Balaam was a prophet of the God of the Hebrews—something that thus appears to throw a significant contradiction between the figure in the Bible and in the Deir Alla inscription. But was the biblical Balaam really a “true prophet”—a prophet of the God of Israel? Is the Deir Alla inscription really fodder against the Bible’s account of Balaam?

Joshua 13:22 states: “Balaam also the son of Beor, the soothsayer, did the children of Israel slay with the sword …” The word soothsayer refers to the use of magic and divinations, and is biblical language used to describe false prophets and magicians. In 19 out of 20 times the Hebrew word is used in the Bible, it is in a negative context.

Further, Numbers 24:1 states: “And when Balaam saw that it pleased the LORD to bless Israel, he went not, as at other times, to seek for enchantments, but he set his face toward the wilderness.” God specifically forbids His people from using enchantments (Leviticus 19:26), and commanded all those who did be put to death (Deuteronomy 18:10). Only false prophets and pagans of the time used these practices.

Thus it becomes clear that the Balaam of the Bible was a pagan, just like in the Deir Alla inscription. Instead, he was used by God, in his unique situation before the Moabite king, to prophesy blessings on the Israelites. This example of God using a false prophet is not unique in the Bible—1 Kings 13 tells the story of a false prophet that was inspired by God to prophesy the death of a true prophet he was hosting for a meal (verses 20-22).

A phrase Balaam used while blessing the Israelites offers more evidence to his true nature: “Who can count the dust of Jacob, and the number of the fourth part of Israel? Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his! (Numbers 23:10). These words could indicate some kind of an admittance of Balaam’s unrighteous deeds. And despite these declared wishes, he certainly came to an ignominious end.

Both the Bible and the Deir Alla inscription describe a pagan who used mystical arts and enchantments to commune with the spirit world. The nearly 3,000 year-old inscription from Deir Alla in no way discredits the biblical account, but on the contrary provides a fascinating corroboration of a well-known Near Eastern figure, both hated and revered—the prophet Balaam.

This story was originally published in February 2017.