The downfall of the northern kingdom of Israel, with the ultimate defeat of the capital Samaria, is clearly described in 2 Kings 18. “And it came to pass … [in] the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria, and besieged it. And at the end of three years they took it …. And the king of Assyria carried Israel away unto Assyria …” (verses 9-11).

It sounds straightforward with plenty of archaeological corroboration: Shalmaneser v is a well-known Assyrian king of this period; Israel’s king Hoshea is likewise attested to on Assyrian inscriptions during this time; Assyria’s defeat of Israel is well documented by archaeology, as is the deportation of the Israelites and “importation” of foreign peoples into the land (as described in 2 Kings 17). Overall, a case of remarkable corroboration for the biblical account.

Apart from one thing: Assyrian annals say that Sargon ii—not his predecessor, Shalmaneser v—defeated Israel. As such, this passage has been pointed to as evidence of biblical error. Is it?

There is more to this event—and to this passage of scripture—than meets the eye.

Sargon’s Record

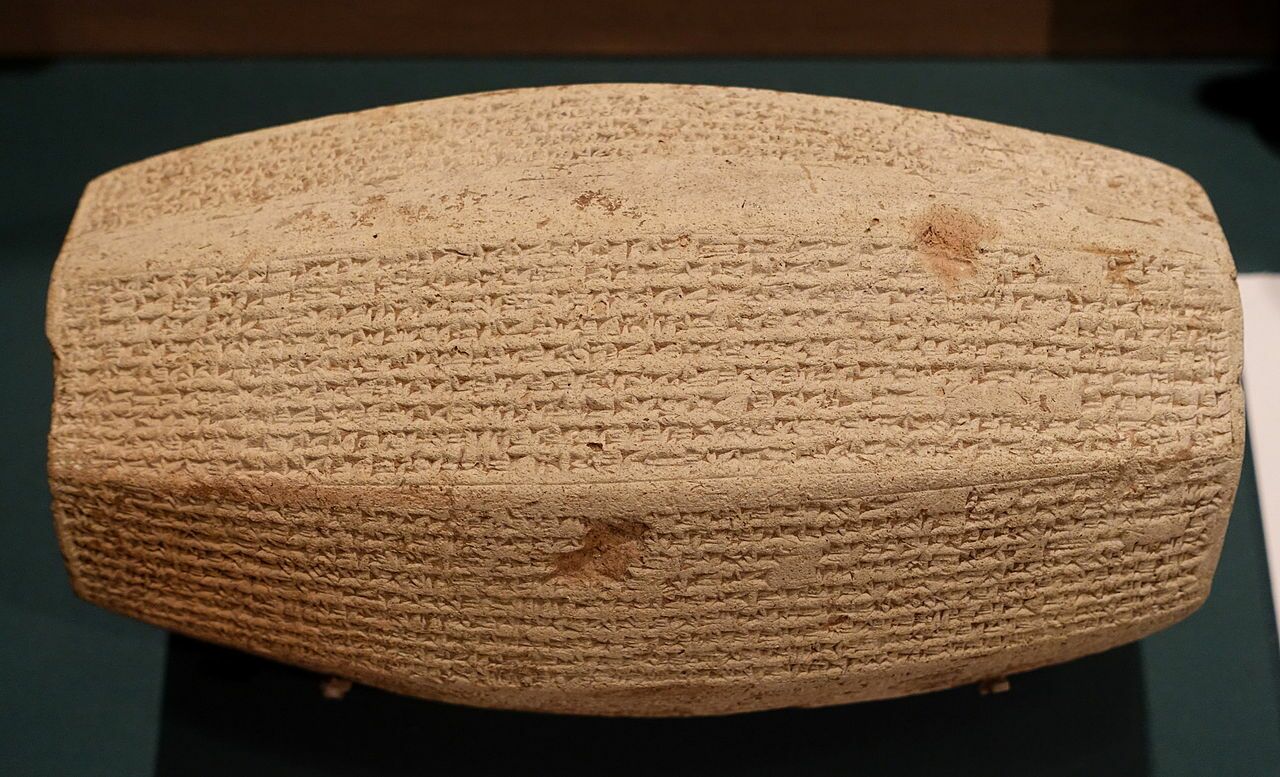

King Sargon ii’s reign is dated from around 721–705 b.c.e. No less than eight of his inscriptions proudly boast of his conquest of Samaria. Note especially the following two partial inscriptions:

“The inhabitants of Samaria … I fought against them … I settled … them in the midst of Assyria. I repopulated Samaria more than before. I brought into it people from countries conquered by my hands ….” (Nimrud Prism)

“I besieged and conquered Samaria ….” (The Great Summary Inscription)

So Sargon ii did it—simple enough. But it’s not.

One suggestion is that Sargon was claiming for himself the triumphs of the former king Shalmaneser. Such false self-attribution was right up the alley for the boastful kings of the ancient world. And the Bible would have no reason to “lie” about the Assyrian king responsible for this event.

Yet what about the dates for this siege? The three-year siege of Samaria is dated to 721–718 b.c.e., fitting right into the start of Sargon’s reign. And to the Bible critic, the history could have easily been misconstrued—if it was written many centuries after the event it describes (a fairly standard assumption).

We therefore have two apparently conflicting claims. In the biblical spirit of “at the mouth of two or three witnesses,” let’s bring in another one.

Babylon’s Record

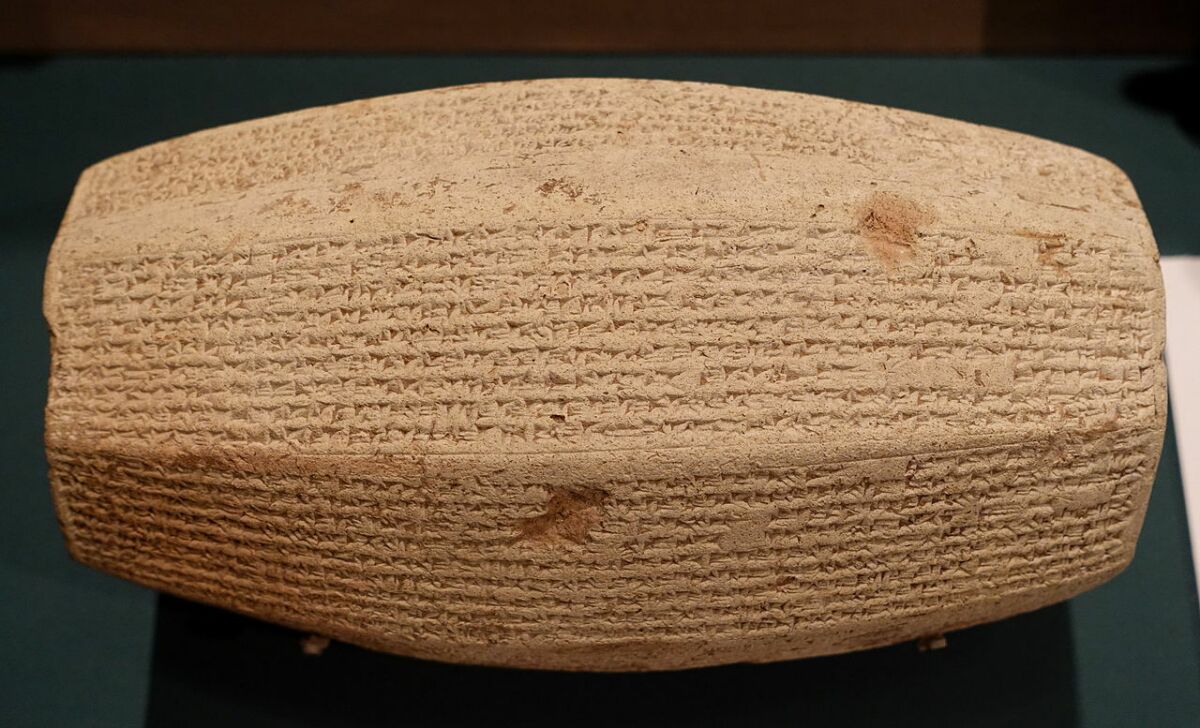

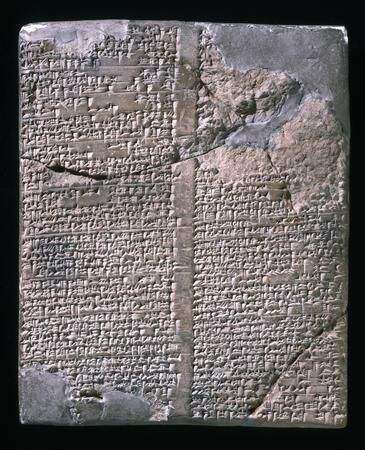

Normally, we would consult the Assyrian Eponym Chronicle, a detailed year-by-year listing of Assyrian campaigns (covering some 160 years of Neo-Assyrian history). Unfortunately, though—in conspiracy-like manner—the events of the years 724–718 b.c.e. are erased. That is to say, the leaders traditionally listed at the start of each year are there, including Shalmaneser and Sargon, but not the events that happened. It’s a glaring blank spot among a generally complete body of events.

There is another ancient chronicle we can turn to, though. The Babylonian Chronicles, dating to around 600 b.c.e. (just over a century after the events at hand), contain a similar listing of important events in Assyrian and Babylonian history. This is what the Babylonian Chronicle i says, regarding Shalmaneser v:

On the 25th day of the month Tebet, Shalmaneser [v] ascended the throne of Assyria [and Akkad]. He ruined Samaria. Year 5: Shalmaneser died in the month of Tebet.

The above statement seems pretty unequivocal, and pairs well with the biblical account (although the case has been made that the Assyrian word translated “ruined” could simply mean “pacification of a region”).

In any case, surely someone’s lying.

But what if all accounts are correct?

High Crimes and Misdemeanors

Sargon ii did not take the throne of Assyria by normal succession. His name, translated as “the legitimate king,” speaks to the court intrigue at the time. Sargon claimed to be the son of the revolutionary king Tiglath-Pileser iii (who reigned before Shalmaneser); however, modern researchers believe this probably was not the case and that Sargon usurped the throne, thus starting his Sargonid dynasty.

It doesn’t help that records of Shalmaneser v’s reign are scarce—and it is unknown exactly how he died.

Let’s return to 2 Kings 18 to reconstruct the series of events: “And it came to pass … [in] the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria, and besieged it” (verse 9).

This verse, set in 721 b.c.e., could fit snugly into the final year of Shalmaneser’s reign. But note the following verse: “And at the end of three years they took it”—not he, Shalmaneser specifically, but they, the Assyrians—“even in the sixth year of Hezekiah, which was the ninth year of Hoshea king of Israel, Samaria was taken.”

“And the king of Assyria carried Israel away unto Assyria …” (verse 11). This verse does not say Shalmaneser specifically did it—simply a king of Assyria (even the “the” is technically not in the Hebrew text). The vague identity of this individual is notable, and could fit with a then-vague idea in Israel of who the rightful ruler of Assyria was. As such, the verse in no way contradicts either of the Assyrian accounts, but gives a whiff of behind-the-scenes treason occurring in the Assyrian royal courts.

This same theme is found in the parallel account in 2 Kings 17: Shalmaneser is clearly named as bringing Hoshea into subjection throughout his rule (verse 3), but it is an unnamed “king of Assyria” that continues and concludes the grueling three-year siege, ultimately conquering Israel and taking it captive (verses 4-6).

Perhaps the decision not to name Sargon in the biblical account at this time was a political hint too—refusing to recognize him as legitimate ruler.

Thus, we re-create the following series of events: Shalmaneser v rules over a subjugated Samaria throughout his reign (2 Kings 17:3); Hoshea forms a conspiracy with Pharaoh So (verse 4); in 721 b.c.e., Shalmaneser orders his army to besiege Samaria (18:9); that same year, he is overthrown by the usurper Sargon ii; Sargon then continues the siege for the remaining period of 2½-3 years, resulting in the final destruction of the capital city of Israel and the northern kingdom in general (verses 10-11).

In such manner, all three accounts—biblical, Assyrian and Babylonian—lock together.

Record of Accuracy

It’s a bit ironic when Sargon ii is used to “disprove” the Bible—because up until the 19th century, he was completely unknown to archaeology. Even the historian Josephus, in his exhaustive writings, failed to mention him. He went totally unrecognized in classical histories.

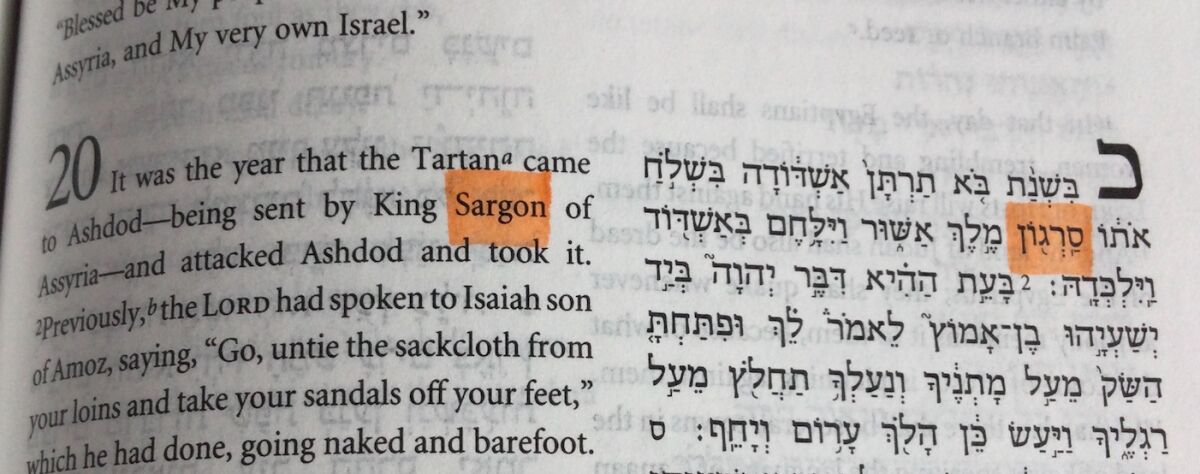

But “unknown” is not the full story. Because Sargon was known historically—from a single Bible reference: Isaiah 20:1 (describing an event much later in Sargon’s reign). As such, the Bible was singled out for either a confused or fabricated reference, or for using an obscure name for another known Assyrian king.

Today, however, Sargon ii is known as one of the most significant kings in Assyrian history, thanks to the deciphering of cuneiform in the late 19th century and the excavation of his chief city, Dur-Sharrukin.

The archaeological discovery of Sargon ii was a remarkable testament to the accuracy of a single standalone biblical verse.

And it seems that something similar could be said for the short biblical description of the conquest of Samaria by an unnamed king of Assyria—revealing a glimpse into what would have been a distant, yet dramatic, Assyrian insurrection.