South of the central highlands of Israel lies the Negev Desert. The capital of this desert region is an oasis city named Beersheba (pronounced in Hebrew “Be’er Sheva”). Four kilometers from this modern city lies the ruins of its ancient namesake. These ruins are filled with rich biblical history.

The Hebrew Bible mentions Beersheba 33 times. Nine times the phrase “from Dan to Beersheba” is used as an expression for the core territory of the nation of Israel (with Dan in the north and Beersheba in the south). But beyond its reference as a border city, Beersheba also played a critical role in the stories of the patriarchs and continued to play an important role throughout Israel’s history. That importance can be witnessed in the remains discovered at the site. In this article, we’ll explore the biblical and archaeological history of Beersheba.

Origins of Beersheba

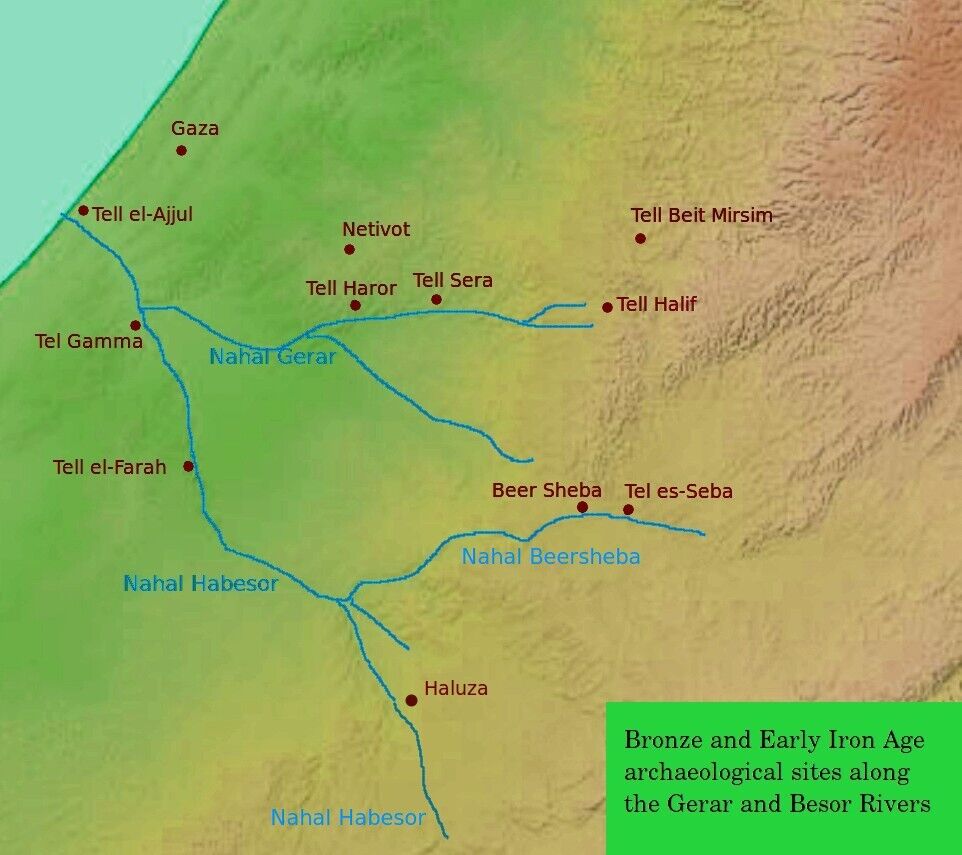

The Bible gives several details about early patriarchal-period Beersheba, including how it got its name. Genesis 20:1 records that Abraham journeyed south from Mamre and “dwelt between Kadesh and Shur; and he sojourned in Gerar.” In this region, Abraham had dealings with Abimelech, Philistine king of Gerar. Gerar is located in the region of the modern-day Nahal Gerar, just northeast of Beersheba.

Following a peculiar incident in which Abimelech made the mistake of taking Abraham’s wife, Sarah, into his harem (not realizing her marriage to Abraham), God appeared to Abimelech in a dream and revealed his error. After the dream, Abimelech returned Sarah to Abraham, along with goods, livestock, and a grant to live in any land controlled by Abimelech: “… Behold, my land is before thee: dwell where it pleaseth thee” (verse 15). Abraham proceeded to settle in nearby Beersheba, though it was not yet named that.

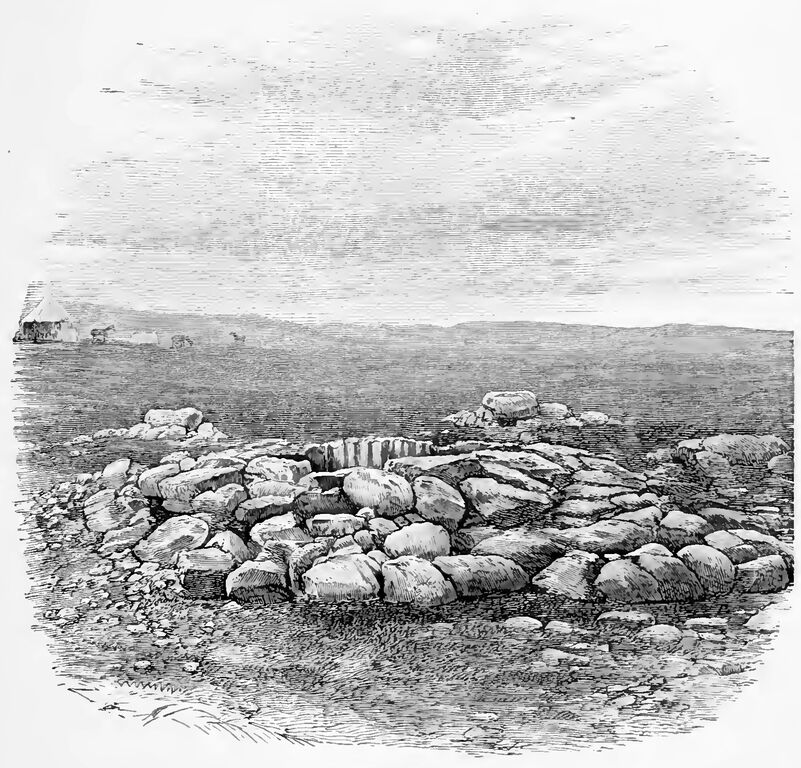

In Genesis 21:23, Abimelech reached out to Abraham and asked for certification that Abraham would not usurp his authority in the land. Abraham gave his word, but also told Abimelech to give back a well that certain of his men had taken. Abimelech swore ignorance of the action performed by his men. At this point, the Bible describes how Beersheba got its name: “And Abraham took sheep and oxen, and gave them unto Abimelech; and they two made a covenant. And Abraham set seven ewe-lambs of the flock by themselves. And Abimelech said unto Abraham: ‘What mean these seven ewe-lambs which thou hast set by themselves?’ And he said: ‘Verily, these seven ewe-lambs shalt thou take of my hand, that it may be a witness unto me, that I have digged this well’. Wherefore that place was called Beer-sheba; because there they swore both of them” (verses 27-31). Beer is the Hebrew word for “well”; sheba (or sheva) is the word for “seven”; thus, the name literally means “well of the seven,” or “well of the sevenfold oath.”

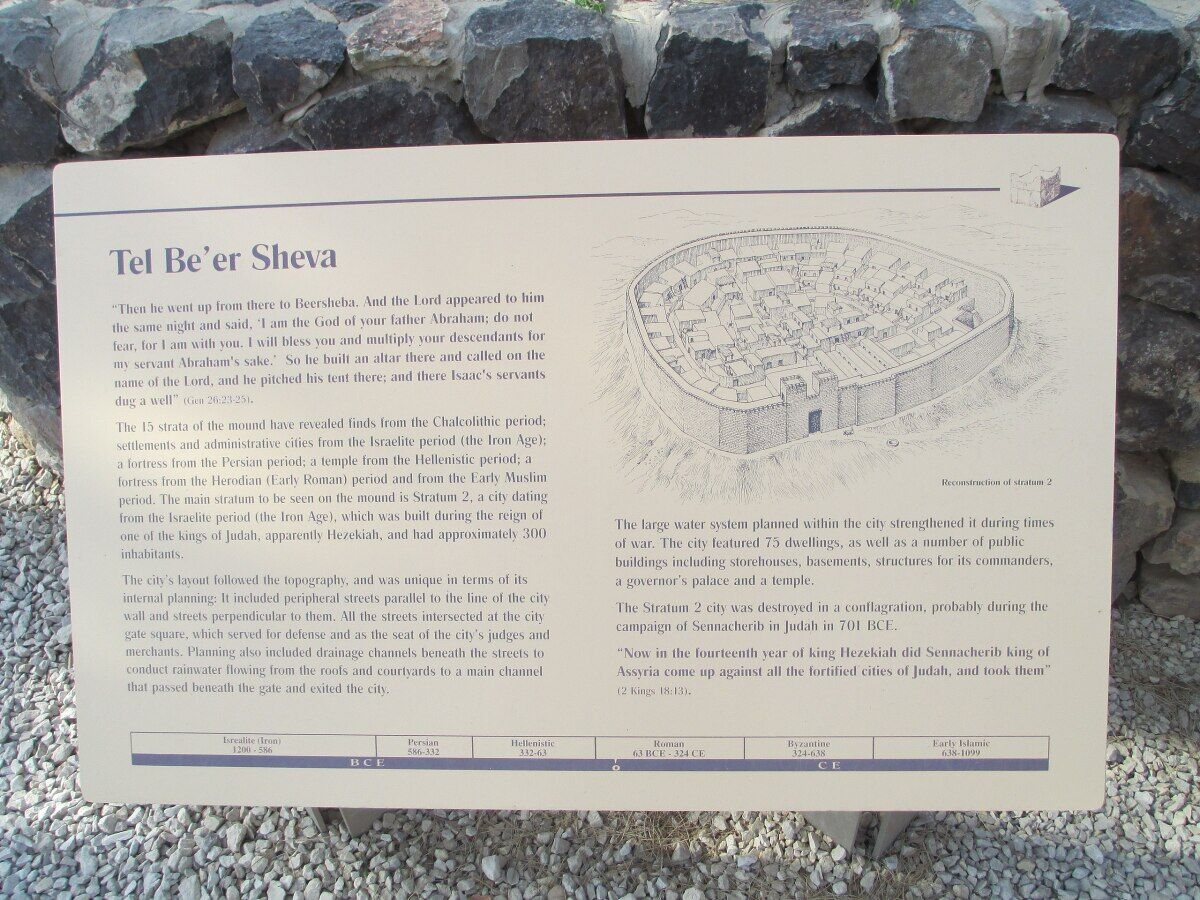

Architecturally, no archaeological evidence of Beersheba has been discovered dating to the age of the patriarchs—rather, the first fortifications discovered at the site begin to appear in the second half of the second millennium b.c.e. The late Prof. Yohanan Aharoni, who excavated the site from 1969 to 1976, wrote that the earliest dating for the structures at Beersheba dated to the 12th to 11th centuries b.c.e.

Yet this is hardly surprising, given the biblical account—and in fact, it fits quite well. Unlike other early, patriarchal-period cities during the first half of the second millennium b.c.e., there is no biblical description of an already existing Canaanite city established in this location. Indeed, until Genesis 21:31, it is an unnamed location. Notable features pointed out at the site merely include a well, a tamarisk tree and another well (verses 25, 33; more on the latter further down)—hardly notable features if this had already been a grand, occupied city-fortress. Another point is that the biblical patriarchs were semi-nomadic tent-dwellers, not city-builders (Genesis 13:3, 12; 18:9; 26:17; 31:33; etc). As Elliot Chodoff summarizes (video below): “[Abraham] comes out here to the desert, to the middle of nowhere. Remember that when Abraham comes here there is no Beersheva. Beersheva is named because of what happens while he’s here. He’s in the open desert. … This is the area where he pitched his tent. He doesn’t build a house. He is a nomad within his land.”

Verse 33 of Genesis 21 records that Abraham “planted a tamarisk-tree in Beer-sheba, and called there on the name of the Lord ….” Translations differ on what all this verse entails, but a standard interpretation is that it was from this location in Beersheba that Abraham began to publish, or proclaim, the name of the Lord. It was from Beersheba that Abraham departed to Moriah to sacrifice Isaac. Isaac himself would later return to dwell in Beersheba.

The Bible records that Isaac was blessed in wealth even above his father, to the point that “the Philistines envied him” (Genesis 26:14). Genesis 26:15 records that men of the Philistines, out of spite, had filled with dirt all of the wells that Abraham had dug, including the well at Beersheba. Verse 18 records that Isaac began a mission to clean out his father’s wells.

Tel Beersheba has at least seven old wells, but one well is traditionally called “Abraham’s well.” This well is known to have been updated by Arabs in the 12th century c.e., as evidenced by an Arabic inscription on a stone 15 courses down into the 13-meter-deep well. Naturally, it is impossible to say for certain if this is one and the same well of Abraham. Nevertheless, it is the one that has been traditionally and consistently associated with him over the centuries, and is a major tourist attraction at the site. (It was also a location at which, at the behest of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin visited with him during a remarkable treaty of peace between the two nations.) A tamarisk tree has since been planted again near the well, in recollection of Abraham doing the same.

Genesis 46:1 says that Jacob later came to Beersheba while en route to Egypt and made sacrifices there. That night, he received a vision that endorsed his journey. This is the final chronological mention of Beersheba for several centuries. No discoveries from a Canaanite occupation of Beersheba have been made, so it seems to have been an unoccupied well site in the Negev until the latter part of the second millennium b.c.e., the start of the Iron Age period and Israel’s ascendance out of initial oppression and obscurity during the judges period.

Iron Age Beersheba (1200–586 b.c.e.)

Beersheba is mentioned next in Joshua 15:28, as being allotted to the tribe of Judah. Later, however, in Joshua 19, Beersheba was reallocated to the tribe of Simeon, who formed a small pocket of territory within Judah. But the main substance of biblical mentions of the site—and corresponding archaeological discoveries—comes later on.

1 Samuel 8:2 states that the Prophet Samuel’s sons “were judges in Beer-sheba.” The Bible describes Samuel living in Ramah at the time, where he heard reports of his sons’ corruption. It was due to the actions of Samuel’s sons in Beersheba, as well as Samuel’s age, that the leaders of Israel requested a king. This, chronologically, takes place during the early to mid-11th century b.c.e.

For Beersheba to have been a base of operations for Israel’s leadership (or judges) at this time, it must have been established as a permanent settlement. And this is what we find in the archaeological record: It is during this same period that archaeological excavations at Tel Beersheba have revealed the earliest construction of buildings at the site, which eventually became an enclosed settlement. Together with housing, pits for grain storage dating to this period were also discovered.

Of course, Israel received its (initially) desired king in the form of Saul. Beersheba is mentioned several times in the monarchical period, mostly in passing. Archaeology, however, has shown us that this is when Beersheba reached its apex. Beersheba was still comparatively diminutive compared to other Israelite cities in the central highlands of Israel. Excavator Prof. Yohanan Aharoni wrote this about his site: “The Iron age city is relatively small. Its area consists of about 10 dunams, compared with about 65 dunams at Megiddo. (There are roughly four dunams in an acre.) However, its defenses were of unusual strength, and a glance at the city plan emerging from the various excavated sections leaves no doubt that this was a well-planned city from its very inception.”

The walls of Beersheba were built in the typical Israelite casemate style, meaning that the walls of homes also made up the fortification walls of the city. Casemate walls were practical and reinforceable. Iron Age Beersheba also featured a four-chambered gatehouse, similar in style to other Israelite gates, as well as a palatial complex, an impressive underground water system, and what appear to be rows for horse stables (similar to those in Israel’s famous chariot city, Megiddo).

The homes of Beersheba were generally built in the four-room style, characteristic of Iron Age Israel. Four-room homes consisted of three long, narrow, open rooms with one enclosed, broad room that intersected the other three. Israelite homes often shared walls. The broad room in the rear of the home also formed the casemate walls around the city. Other contemporary Negev sites share a similar layout. Most of the walls were built on a boulder and mortar foundation but consisted primarily of mudbricks. The houses were formed around a central courtyard which could hold herds of livestock or facilitate traders.

Prof. Ze’ev Herzog suggests that the reason Beersheba focused so much on fortification was because of “the powerful Amalekites who dominated the Negev during the early part of King Saul’s reign (1 Samuel 15)” (“Beer-sheba of the Patriarchs”). The Amalekites were a warring tribe potentially based in the nearby Tel Masos, a site which Prof. Moshe Kochavi believes to be an Amalekite settlement.

Archaeology shows that shortly after the reign of Saul, some of the city-tel was leveled (destroying any older artifacts), and a royal urban centre was constructed at Beersheba, presumably by David.

Beersheba and Paganism

The eighth-century b.c.e. prophet Amos used the example of Beersheba to warn the Israelites against descending into paganism. Amos 5:4-5 states: “For thus saith the Lord unto the house of Israel, Seek ye me, and ye shall live: But seek not Bethel, nor enter into Gilgal, and pass not to Beersheba: for Gilgal shall surely go into captivity, and Bethel shall come to nought” (King James Version). The warning points to Beersheba as having become a place of pagan pilgrimage.

One of the most striking finds made at Tel Beersheba is that of a horned altar, discovered by Professor Aharoni in secondary use in a wall at the site. The since-reconstructed altar exhibits prominent “horns” on the four corners—a feature of Israelite altars described in numerous biblical passages (e.g. Exodus 27:2; 29:12; 1 Kings 1:50). The Beersheba altar constituted the first horned altar ever found in Israel (numerous other “altar horns” have since been found—for example, at Tel Shiloh).

While the corner “horns” do fit the biblical mandate for altars, the presence of such an altar at Beersheba does not. Likewise, the iron-hewn nature of the altar stones contravenes the command found in Exodus 20:22 and Joshua 8:31 that such altars be made of whole stones, untouched by iron tools. As such, the altar is evidently pagan in nature, fitting with the words of the Prophet Amos (not to mention the dating for its use).

2 Kings 18 and 2 Chronicles 31 relate that at the end of the eighth century b.c.e., the righteous King Hezekiah enforced religious reforms throughout Judah. Hezekiah broke down “high places,” or bamot—elevated open-air cultic shrines—along with their altars. “Hath not the same Hezekiah taken away his high places and his altars, and commanded Judah and Jerusalem, saying, Ye shall worship before one altar, and burn incense upon it?” (2 Chronicles 32:12; kjv).

Actually, the discovery of this Beersheba altar in secondary use in a wall was linked by the excavators to what these passages describe: Hezekiah’s purge of pagan bamot and altars throughout the land. Professor Aharoni certainly believed this to be the case. Professor Herzog summarized: “[A]lthough we do not have an archaeological proof that the intentional abolishment of the cultic centers of Arad and Tel Beer-sheba was made under orders from Hezekiah, the combined archaeological and biblical data point in favor of this possibility” (“Perspectives on Southern Israel’s Cult Centralization: Arad and Beer-sheba”).

Not long afterward, Beersheba was destroyed, swept up in the cataclysmic campaign of Assyrian King Sennacherib at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. 2 Kings 18:13 reads: “Now in the fourteenth year of king Hezekiah did Sennacherib king of Assyria come up against all the fortified cities of Judah [which would include Beersheba], and took them.” There was some debate, up until recently, about this destruction layer relating to the Babylonian invasion, which occurred a century later. However, thanks to the newly emerging discipline of archaeomagnetism, this destruction has been securely pinned down to the earlier Assyrian invasion. Professor Herzog wrote, “Tel Beer-sheba was entirely abandoned after its destruction during Sennacherib’s campaign.”

The next chronological biblical mention of the location is during the reign of Josiah (2 Kings 23:8), which again condemns a reemergence of pagan worship at the site. Archaeologically, there is evidence for a short-lived attempt to reestablish the site following Sennacherib’s invasion, before it was ultimately abandoned.

Rebuilding

The book of Nehemiah describes a resettling of the Jewish people in Beersheba following their deportation by the Babylonians in the sixth century b.c.e. (Nehemiah 11:27, 30). New discoveries have revealed just such a reoccupation, which lasted on into the Second Temple Period, with the establishment of a small fortress during the Persian period, then a temple during the fraught Hellenistic period (a period often described as one of religious anarchy), and the construction a larger, expanded fortress during the Herodian period, up until the first century c.e. and the First Jewish Revolt.

In 2019, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced the discovery of a rare Jewish settlement dating to this Herodian period. Ritual baths, stone vessels, pottery, and olive and date pits were all discovered during the excavation. Notably, these discoveries included one of the oldest depictions of a nine-branched menorah on an oil-lamp fragment.

The menorah of the temple had seven branches, as highlighted in Exodus 25:31-40. But the Babylonian Talmud instructs Jews to not create candelabra that replicate the temple menorah, hence the utilization of nine-branched menorahs and the depiction as such on the pottery item.

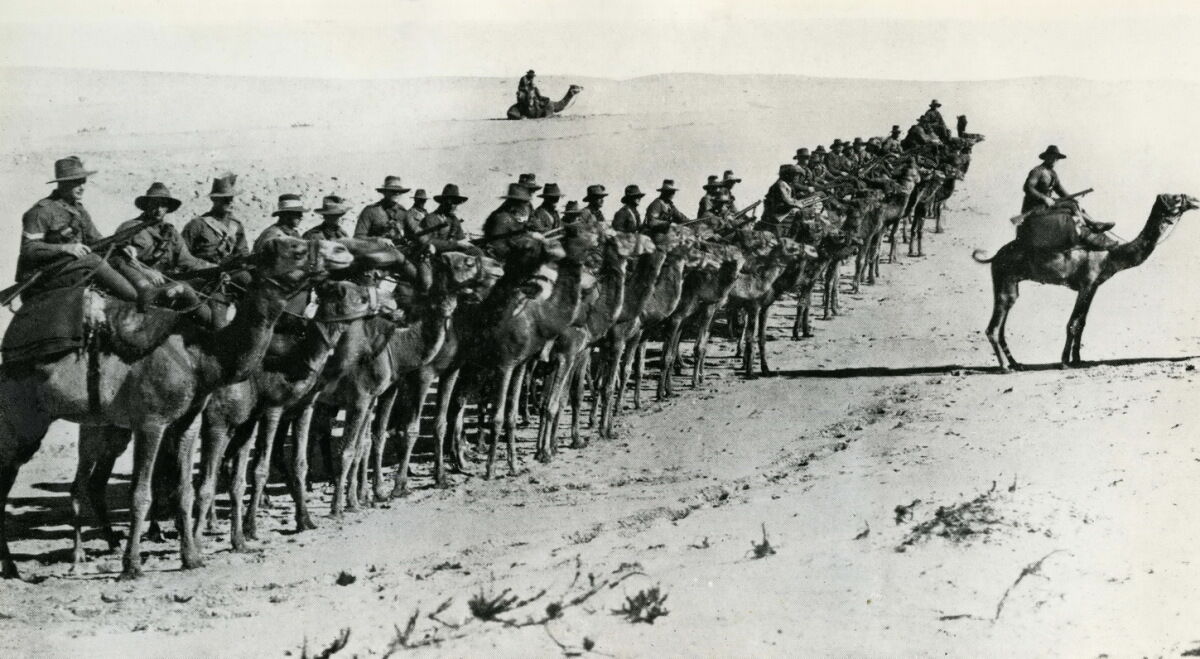

Escape routes and tunnels have been uncovered as well, and given the first-century c.e. dating, it is believed that they must have been used by rebels for hiding. Signs of conflagration from the Great Revolt were also discovered. Following the putting down of the rebellion in 70 c.e. and again in 135 c.e. (the Bar Kokhba Revolt), the site became home to a Roman fortress in the ensuing centuries. Later, it served as an Arab fortress during the early Islamic period, and then as a fortification again for the Ottoman Turks in World War i, where they were famously defeated by horse- and camel-mounted Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (anzac) cavalry in 1917.

Beersheba has a rich history, weaved from the patriarchal period to the present. While debate continues among archaeologists over particular details, there is no denying the wider picture: that Beersheba played an important role historically and biblically.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer