Azekah was one of ancient Israel’s most strategic cities. Settled thousands of years ago, this important city is attested to in both biblical and secular records, and corroborated by archaeological discoveries.

Situated about 30 kilometers west of Jerusalem, Azekah sits at the heart of the Judean “Shephelah,” or lowlands. Perched on a high hill overlooking a tactical route connecting the coastal plains with the mountains, it was a strategic location for those who controlled it.

Azekah is mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible, especially in the context of conflicts and conquests—from David’s battle with Goliath, to the Assyrian king Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah, to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of the kingdom. Here we review Azekah’s history, as revealed by the Bible and archaeology.

Excavating Azekah

In 1898, British archaeologists F. J. Bliss and R. A. S. Macalister excavated Tel Azekah, making it one of the first sites to be excavated in the Holy Land. They were able to differentiate between two main periods: the pre-Israelite and Israelite. However, further analysis has revealed more distinct and varied strata.

In the 1990s, Yehuda Dagan surveyed the site and concluded that it was first settled in the Early Bronze Age (third millennium b.c.e.) with continued settlements up to the Byzantine period (mid-first millennium c.e.). In 2009, a comprehensive ground-penetrating survey revealed more specifics, including the potential size and impact each period had on the site. This initial survey showed that there were two peak periods: the Late Bronze Age (circa 1550–1200 b.c.e.) and Iron Age ii (or period of Judahite monarchy, circa 1000–586 b.c.e.). Excavations in 2012 and thereafter have yielded tremendous results and have supplied much of the understanding of Azekah we have today.

Canaanite Azekah

The discovery of an immense amount of Bronze Age pottery at Azekah points to a strong and prosperous Canaanite presence at the location during the second millennium b.c.e. A large amount of Egyptian pottery and Egyptian motifs, such as scarabs, were also discovered, indicating that Azekah was under strong Egyptian influence, potentially even having direct connections to the Egyptian administration.

The Canaanite construction at the site—including a 6 meter high wall—dates to around 1700 b.c.e. Canaanite occupation continued for several hundred years. The Bible testifies to the existence of Azekah during Joshua’s conquest of Canaan: Israel had formed a league with Gibeon, and Joshua and the Israelites came to its aid in fighting off attacking Amorites. Those attackers who were not slaughtered were chased back “to Azekah.” Additionally, God rained down giant hailstones on the fleeing Amorites “unto Azekah” (Joshua 10:10-11).

At the end of the Late Bronze Age, Azekah “fell victim to devastation, either by an unknown aggressor or from a natural disaster,” writes Sabine Kleiman et al in “Late Bronze Age Azekah—An Almost Forgotten Story” (summarizing the results of the Lautenschläger Azekah Expedition, 2012–2016). Following this destruction, Azekah apparently remained in ruins for several centuries.

Israelite Azekah

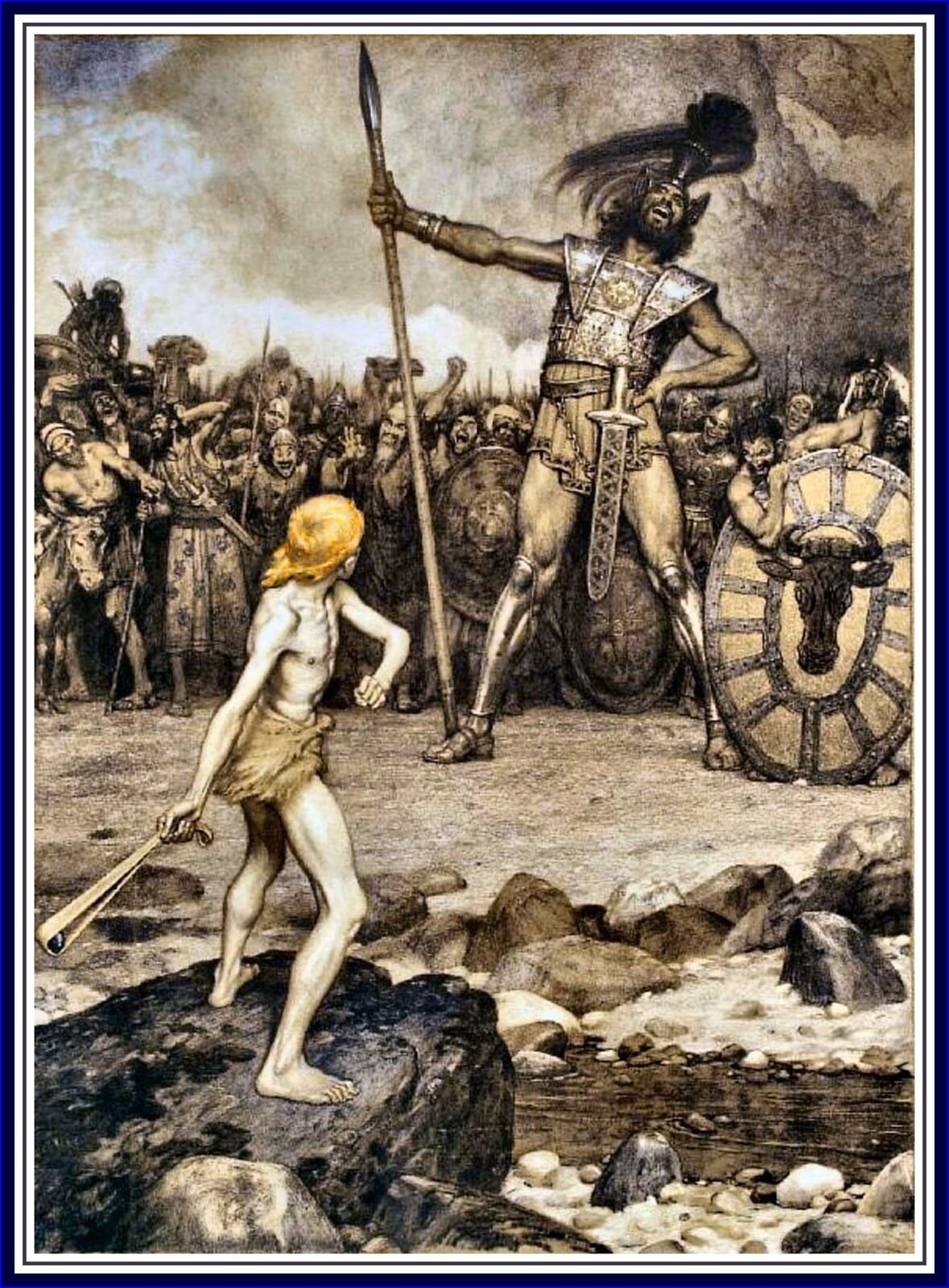

When tribal allotment was apportioned, Azekah was given to the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15:35). Azekah eventually became the backdrop for one of history’s most legendary confrontations: David vs. Goliath. 1 Samuel 17:1 highlights that this event took place between Socoh and Azekah.

Naturally, archaeology can hardly be expected to substantiate this specific confrontation between these two individuals. But a remarkable amount of peripheral evidence has been discovered, substantiating the broader geopolitical situation at this time, including various particulars relating to this 1 Samuel 17 account. (You can read some examples in our articles “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa” and “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines.”) And despite the inroads into this region made by the Philistines at this time, thanks to the success of David’s campaigns, the Philistines were driven back toward the coast.

Azekah, under the control of Judah, became a strategic stronghold under the Davidic monarchy. It is listed in 2 Chronicles 11:9 as one of the cities that King Rehoboam fortified. The Bible notes that he made the cities “exceeding strong” (verse 12). Azekah’s earliest excavators dated a large fortress they discovered on the south-east side of the hill to this period (end of the 10th century b.c.e.); this dating, however, has come under dispute, with later archaeologists arguing that it dates to roughly a century later.

Whatever the case regarding this specific portion of the city, the strength of Judahite Azekah during the Iron ii period is aptly attested to, not just by the Bible, but most notably by Israel’s arch-enemy: Assyria.

Assyrian Azekah (Temporarily)

In the eighth century b.c.e., the Assyrians dominated the Middle East. The northern kingdom of Israel had already been invaded and taken captive. Near the end of the eighth century, Assyria returned under the rule of King Sennacherib to squash the Judahite kingdom, ruled at the time by King Hezekiah. Sennacherib attacked “all the fortified cities of Judah, and took them” (2 Kings 18:3)—a reference undoubtedly including the “fortified” city that was Azekah (2 Chronicles 11:9).

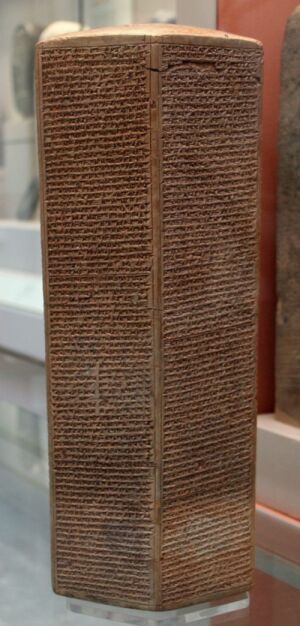

The Assyrians were swift in their conquest. Assyria’s blitzkrieg campaign against Judah is well documented throughout archaeology. Sennacherib’s prisms detail his attacks (you can read about them here).

Most famous among the cities that Sennacherib boasted of conquering was, of course, Lachish—Judah’s number-two city—with a gigantic wall relief of the siege adorning the king’s palace in Nineveh. (As the Bible relates—and as archaeology and Sennacherib’s inscriptions are suspiciously silent about—the king failed to conquer Judah’s capital, Jerusalem.)

Sennacherib did, however, also boast of his conquest of Azekah. And in his account of the conquest of this city, he adds some fascinating details about it. The Azekah Inscription, though fragmentary, reads as follows:

The city of Azekah … located on a mountain ridge, like pointed iron daggers without number reaching high to heaven. [Its walls] were strong and rivaled the highest mountains … [by means of beaten (earth) ra]mps, battering rams … I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated … they had seen [the approach of my cav]alry, and they had heard the roar of the mighty troops of the god Ashur, and [their] he[arts] became afraid … [The city Azekah I besieged,] I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated, [I burned with fire] ….

Sennacherib makes particular note of the sheer height of the towering fortress, on top of the elevated “mountain” (which anyone who has visited the site can attest to). In his inscription, Sennacherib noted that he used a beaten earth ramp and battering rams against Azekah. This method of conquest (which he used in other locations, such as Lachish, as evidenced by the Lachish wall reliefs and excavations at the site) has also been confirmed by excavations at Tel Azekah.

In the summer of 2020, archaeologists led by Tel Aviv University’s Prof. Oded Lipschits uncovered traces of this Assyrian siege ramp. The archaeologists were initially perplexed: They were finding a prevalence of much earlier Canaanite remains associated with the ramp. This confusing mixture didn’t make sense until they realized the Assyrians had repurposed 1,000-year-old outer Canaanite remains of the city to construct their siege ramp.

Babylonian Destruction

Archaeology reveals that Azekah was rebuilt a few decades after Sennacherib’s conquest. But fell again to the Babylonians in the early sixth century b.c.e. Jeremiah 34:7 details that “when the king of Babylon’s army fought against Jerusalem, and against all the cities of Judah that were left, against Lachish and against Azekah; for these alone remained of the cities of Judah as fortified cities.”

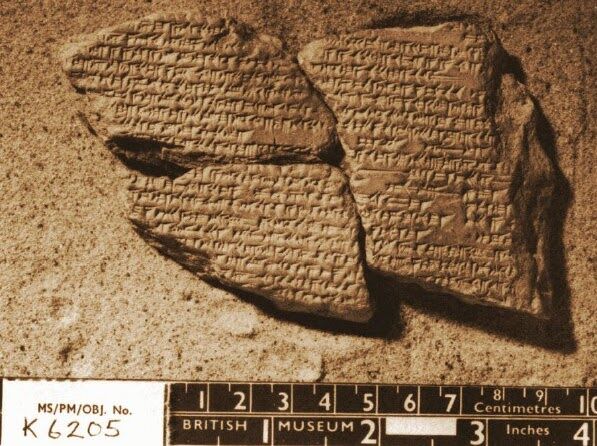

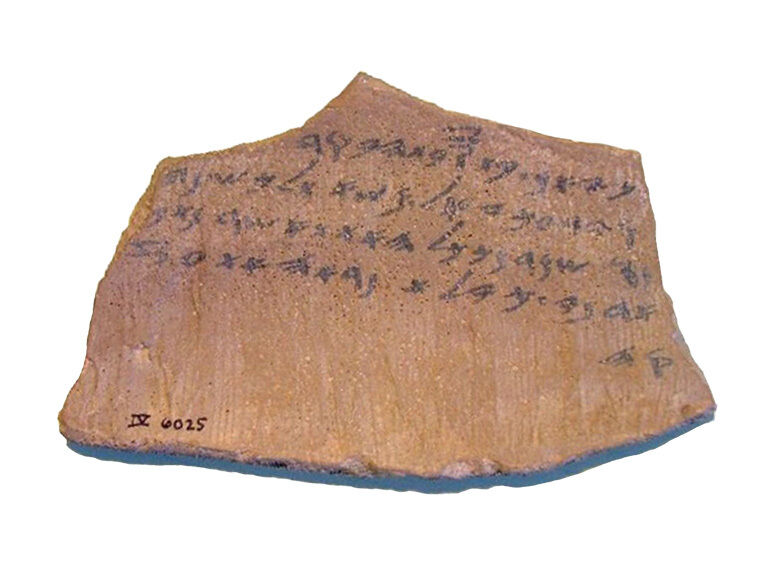

Eighteen ostraca were found in the Babylonian destruction layer at Lachish. The letters were sent by Hosha’yahu, the commander of a small outpost north of Lachish, to Ya’osh (Joash), the military governor of Lachish. Ostracon no. 4 says, “May Yahweh cause my lord to hear reports of good news this very day …. Then it will be known that we are watching the (fire) signals of Lachish according to the code which my lord gave us for we cannot see Azekah.”

Hosha’yahu was anxiously waiting to see fire signals from Lachish because he couldn’t see a signal from Azekah. Had Azekah already been conquered? (Note that the Bible itself describes fire signals being used in this context of Babylon’s invasion—see Jeremiah 6:1.)

Azekah Reborn

Like a phoenix, Azekah repeatedly rose from the ashes. The city’s location and strategic value meant it was often reinhabited. Nehemiah 11:30 states that after the Babylonian exile, the returned Jews rebuilt and reoccupied Azekah. Excavations have revealed that indeed, Azekah remained inhabited through the Persian, as well as Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods, providing an abundance of rich history to the already layered site.

Azekah entered its 11th season of excavation on July 16. As more and more layers are uncovered, Azekah remains among the most important biblical sites. Whether as the backdrop to one of the most famous battles in history, or as an extremely strategic stronghold, we await to see what more will come out of this fascinating location.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer