It is perhaps the most famous city in the world. A city known as the “closest to heaven,” the “center of the Earth,” the holiest place on the planet. Its name means “city of peace,” but this location ranks as one of the most warred-over, bloodied pieces of land: Jerusalem.

Our series on Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities has taken us all over Israel’s archaeological sites: to the first city conquered in the Promised Land—Jericho; to the biggest city in the land—Hazor; to the northernmost city—Tel Dan. And more. All of these cities are fascinating in their own right, but none is quite as special as Jerusalem.

Let’s dig beneath the surface and examine what archaeologists have discovered, and what history tells us, about this truly amazing city.

Jerusalem’s Beginnings

Jerusalem of old was far smaller than it is today. Initially, the city started out atop a small crescent-shaped mountain ridge (later known as Mount Zion). Over the years, the city expanded northward and westward to include the area of today’s Old City and Temple Mount, as well as sprawling suburbs. The first evidence of settlement in Jerusalem dates roughly to 3,500 b.c.e. Yet it wasn’t until the 1800s b.c.e. that Jerusalem got its first city wall. Interestingly, this is also the general time frame for the biblical King of Salem, Melchizedek.

Genesis 14 describes the history of a league of foreign kings sweeping down and conquering Sodom and Gomorrah, capturing Abraham’s nephew Lot. Abraham armed his servants and took off in pursuit of the conquering kings, overcoming them and freeing Lot and the other captives. During victory celebrations, “Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine; and he was priest of God the Most High” (verse 18). Melchizedek then proceeded to bless Abraham, and Abraham gave Him a tithe of his wealth (verse 20). This “Salem” that Melchizedek ruled over was congruous with ancient Jerusalem. Not only are the names connected, but Psalm 76:2 also equates “Salem” with “Zion”—the original inhabited mountain of Jerusalem. Melchizedek would have been on the scene most likely during the 1800s b.c.e.—and thus it is entirely possible that He could have established Jerusalem’s first city foundations and wall dating to that time period.

In “Salem’s” intervening centuries before the arrival of the Israelites, it became a Canaanite stronghold by the name of “Jebus” (Judges 19:10: “Jebus—the same is Jerusalem”). The city, like others throughout Canaan, was subservient to Egypt. Significant inscriptional references linked to Canaanite Jebus come from the Amarna Letters.

To Amarna: From Jerusalem

The Amarna Letters are a trove of documents found at ancient Amarna in Egypt, dating to the 14th century b.c.e. The “letters”—or rather, clay tablets—are the desperate correspondence from leaders of Canaan to Egypt’s pharaoh, asking urgently for help against the invading “Habiru” nomads that were taking over the land. The linguistic similarities between Habiru and Hebrew are tantalizingly similar—and the dating of the letters fits the general time frame of the Israelites entry into the Promised Land. (These Habiru are also known as Hapiru or ‘Apiru.) The correspondence from the Jerusalemite leader to Egypt is no exception to the desperation faced by these Canaanites. Here are some short excerpts from the mayor of Jerusalem’s letters to the pharaoh (emphasis added):

Message of Abdi-Heba [“mayor” of Jerusalem], your servant … May the king [pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted … Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord. The king has no lands. That ‘Apiru has plundered all the lands of the king. If there are archers this year, the lands of the king, my lord, will remain …

Message of Abdi-Heba, your servant … The land of the king deserted to the Hapiru … May the king give heed to Abdi-Heba, your servant, and send archers to restore the land of the king to the king. If there are no archers, the land of the king will desert to the Hapiru.

The Bible does not describe a conquest of Jerusalem during the time of Joshua (rather, it is specified that the king of Jerusalem was killed in a distant battle—Joshua 10). The Bible instead indicates that Jerusalem must have been conquered sometime after Joshua’s death (Judges 1:1, 8). This could explain why, as Abdi-Heba fearfully declared, virtually all the surrounding lands of Canaan had already fallen, yet Jerusalem still remained.

Yet even after this evidently post-Joshua conquering of Jerusalem by the Israelites, the Jebusites continued to inhabit the city (Judges 1:21). It would not be until the time of King David that the city would finally come under full Israelite control.

One final note about Abdi-Heba. In one of his letters to the pharaoh, he makes an interesting statement: “As the king [pharaoh] has placed his name in Jerusalem forever, he cannot abandon it ….” This is a phrase that God uses to describe Jerusalem. “[T]he Lord said: ‘In Jerusalem shall My name be for ever.’“ (2 Chronicles 33:4). This was not going to be the place for the “eternal” name of the pharaoh—certainly very few people today would even think of a “pharaoh” in terms of Jerusalem’s governance. Rather, this would be a place where God’s name would be forever!

During excavations in Jerusalem in 2010, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar and her team discovered an Akkadian tablet fragment, dating contemporaneously to the Amarna Letters. This tablet is believed to have been written by a royal scribe, and would have made up a portion perhaps of an archival copy of this kind of correspondence between the king of Jerusalem and the pharaoh.

David’s Jerusalem

By the time David came on the scene, the Jebusites had grown confident in their city and secure location. No doubt the 350-plus years that they had lived in Jebus during the time of the judges had given them a false sense of security. At this point in Israel, Saul had died fighting the Philistines, and David had reigned as king over Judah from Hebron for seven and a half years. Now, all Israel came to accept David as king—and David’s first move was to set up Jerusalem as his capital. Jerusalem was a city important for uniting Judah with the other tribes—especially because it was a border city, nestled directly between the tribal allotments of Judah and Benjamin. 2 Samuel 5:6 states:

And the king and his men went to Jerusalem against the Jebusites, the inhabitants of the land, who spoke unto David, saying: ‘Except thou take away the blind and the lame, thou shalt not come in hither’; thinking: ‘David cannot come in hither.’

This taunt only provided a challenge for David’s men. Joab, David’s nephew, led a group of men through a water conduit up into the city and overthrew it, subsequently settling himself into the position of captain over Israel’s army (verse 8; 1 Chronicles 11:5-7). The city then became known as the “City of David.”

During her 2008 excavations in the City of David, Dr. Mazar’s team stumbled upon a tunnel dating to this time period—the 10th century b.c.e. (this article will mention Dr. Mazar a number of times, as she has been one of Jerusalem’s chief excavators in the past decade). The tunnel, still blocked by debris, was at least 50 meters (160 feet) long, cut through a natural crack in the bedrock and walled up on both sides, barely allowing passage for a man to squeeze through. This tunnel, which may have originally been used to channel water, has been identified as a candidate for the conduit through which Joab and his men infiltrated and conquered Jebus.

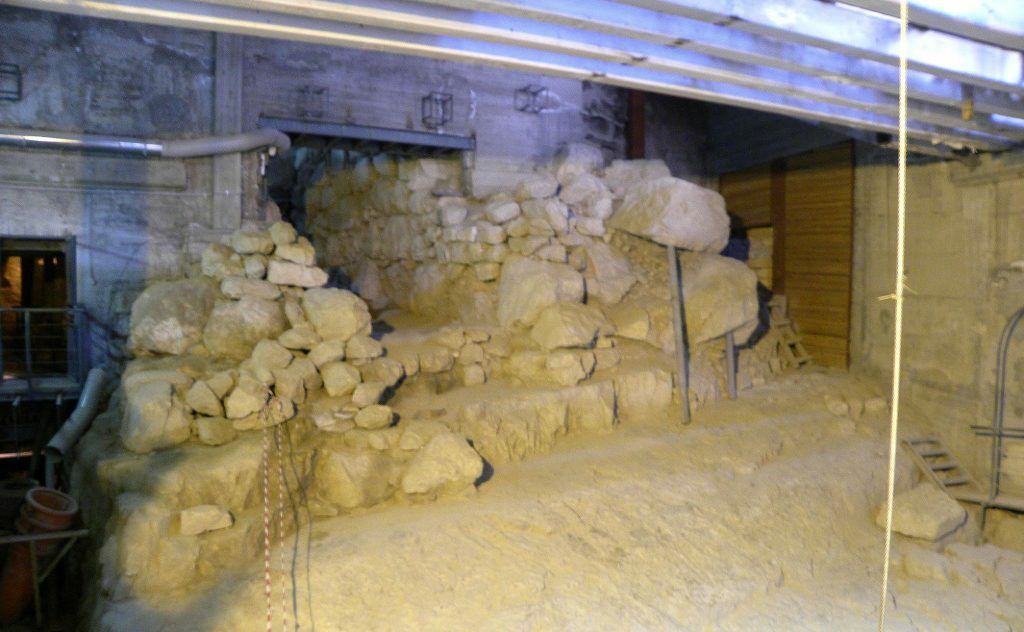

And so Jerusalem became Israel’s capital city. Much additional construction was accomplished by David. One of the monumental constructions attributed to him is the giant Stepped Stone Structure. This magnificent supporting structure was excavated and dated by Dr. Mazar to around the start of the 10th century b.c.e. This structure was built on the furthest northeastern part of the original city of Jebus. It appears that the Jebusites could not expand their city further north up the mountain ridge due to a large gap in the bedrock. With the huge amount of national support and infrastructure available to David, however, the Stepped Stone Structure was probably built to fill in this gap in the bedrock and allow the city of Jerusalem to further expand north.

The Stepped Stone Structure was also vital for supporting a very significant building—the Large Stone Structure.

David’s Palace

If the term “Large Stone Structure” sounds a little mundane, its other title certainly isn’t—David’s palace. This structure, planted directly atop and beyond the Stepped Stone Structure, dates to the 10th century b.c.e., and was enormous. The wall of this building was up to 3 meters (10 feet) wide and 30 meters (100 feet) long! Added to that, another 5-meter-wide wall was unearthed belonging to the structure. Based on the archaeological evidence, as well as the scriptural record, Dr. Mazar concluded that this must have been the palace of King David. It was the most impressive building on the site, for the time period. It was at the highest point of the city. Its pottery dated to the time of David—with pottery found beneath dating to just before his arrival. Certainly a large building project had begun in the city under David—and indeed, the Bible mentions that one of those large projects, supported by the king of Tyre, was the building of David’s palace! (2 Samuel 5:11).

Another piece of evidence Dr. Mazar used to identify this magnificent building as David’s palace was 2 Samuel 5:17. “[A]ll the Philistines went up to seek David; and David heard of it, and went down to the hold.” This verse shows that David had to have been dwelling somewhere high up atop the City of David—and this “Large Stone Structure” was right on the summit. Yet during this threat from the Philistines, he went down into the lower parts of the city—more closely shielded by the fortifications, and where he could assemble his troops to attack.

As big as this palace was, only about 20 percent of it has thus far been excavated. Future excavations are in the planning stages.

Jerusalem’s Expansion

Toward the end of David’s reign, a fierce plague swept through Israel as punishment for an order he had given to conduct a census of the fighting men of Israel. In order to stay the plague, God commanded David to offer sacrifices north of the City of David—on a threshingfloor owned by the Jebusite Ornan (2 Chronicles 21). David bought the threshingfloor and set up an altar. This would become the site of the future temple of God to be built by David’s son Solomon.

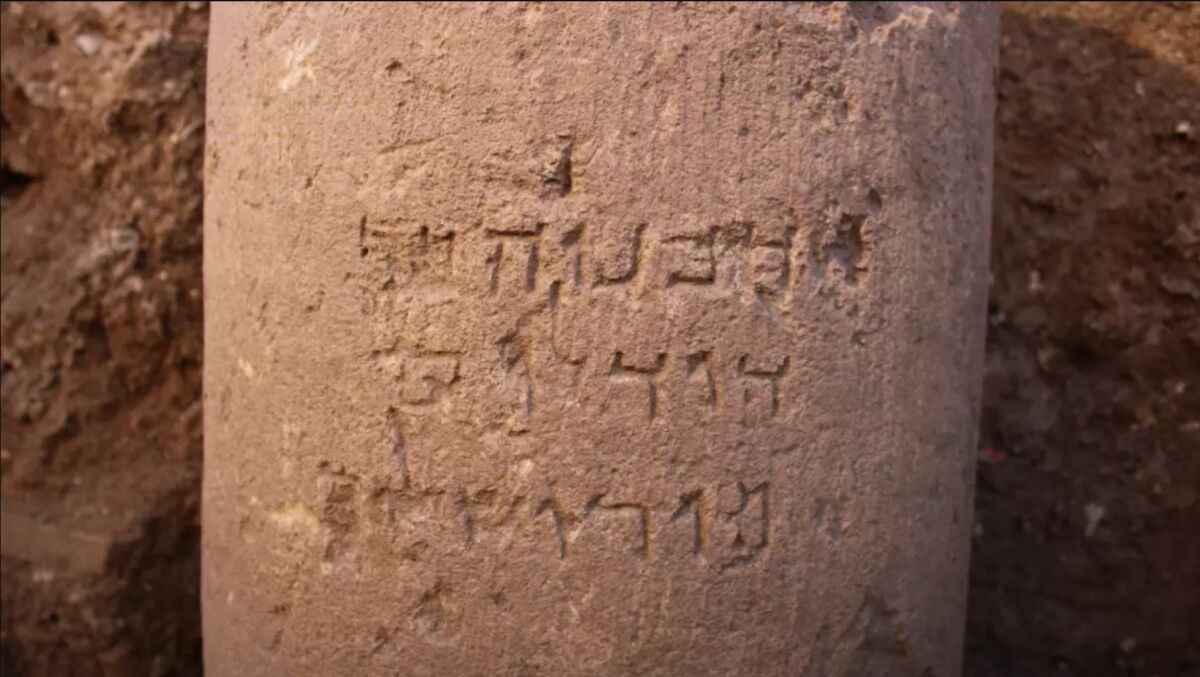

Solomon greatly expanded the city of Jerusalem much further north along the mountainous ridge to include this altar and threshingfloor, developing them into the grand site for the temple. The Bible states that he built a powerful wall around the expanded city (1 Kings 9:15). This wall, too, has been found. Dating to the 10th century, it is made up of massive individual blocks (the largest hewn stones anywhere in Israel during the First Temple Period). The wall also makes up a large tower gate, known as the Water Gate (due to its possible link with the Water Gate of Nehemiah 3:26). This wall thus far exposed is 70 meters (230 feet) long and 6 meters (20 feet) tall. In addition, the inner building that it protected contained the largest storage jars, or pithoi, ever found in Jerusalem, measuring over a meter tall. Further north of the wall, another broken pithos (singular) was found, bearing the earliest alphabetical inscription ever found in Jerusalem. The preserved letters indicate the vessel was used to contain wine.

After Solomon’s rule ended, his son, Rehoboam, took the throne—and chaos ensued. Because of Solomon’s sins as king, and Rehoboam’s harsh treatment of fellow Israelite workmen, the northern 10 tribes of Israel split away to create the northern kingdom, with their capital in Tirzah (later Samaria). Jerusalem remained the capital city for the southern kingdom of Judah (a kingdom to which the tribes of Levi and Benjamin also joined).

King Hezekiah’s Artifacts

It is not possible to go through a full chronological list of Jerusalem’s history and archaeology in this article. We will briefly cover particularly significant events in relation to the more impressive archaeological finds that have been discovered.

We now jump to the time of Hezekiah. This man reigned during the latter half of the eighth century b.c.e. His reign saw the invasion of Assyria into the southern kingdom of Judah, with the attackers notably capturing the major city of Lachish (2 Kings 18:17). The Bible describes how the Assyrians prepared to destroy Jerusalem, issuing terrifying threats to King Hezekiah. Hezekiah initially delivered tribute to assuage the Assyrians (verses 14-16), but that did not stop their intent to conquer the city. After a desperate prayer to God for safety, Hezekiah was informed by the Prophet Isaiah that the Assyrians would not so much as shoot an arrow against Jerusalem. The Assyrians were killed overnight by an angel (2 Kings 19:34-36).

Interestingly, on an Assyrian artifact known as Sennacherib’s Prism, the king boasts: “As for Hezekiah, I shut him up like a caged bird in his royal city of Jerusalem.” The text goes on to delineate the initial tribute he had received from Hezekiah. Yet it makes no mention of an attack on, let alone conquest of, Jerusalem. Just as the Bible says—he couldn’t! Of course, this wasn’t something the boastful king of Assyria would admit.

Dating to this same time period, as a precaution against the Assyrians, King Hezekiah had taken counsel to divert Jerusalem’s outer water sources into the city. Work began on a conduit that would consolidate water within the city walls (2 Chronicles 32:1-4, 30; 2 Kings 20:20). This remarkable conduit has been found, stretching 530 meters (1740 feet) through the bedrock underneath Jerusalem. Incredibly, the bottom end of the long tunnel is only 30 centimeters lower than the origin point—coming out to a gradient of only 0.6 percent. Furthermore, the tunnel was cut through from both ends—scientists have only speculated as to how this was accomplished. Within this tunnel, an inscription stone had been etched commemorating the massive effort.

In 2009, a bulla (seal imprint) was discovered by Dr. Mazar’s team on the Ophel ridge of Jerusalem, and was tucked away for processing. It wasn’t until 2015 that it was fully examined—and to the astonishment of the archaeologists, the ancient Hebrew script from the royal seal read as follows:

Belonging to Hezekiah, [son of] Ahaz, king of Judah.

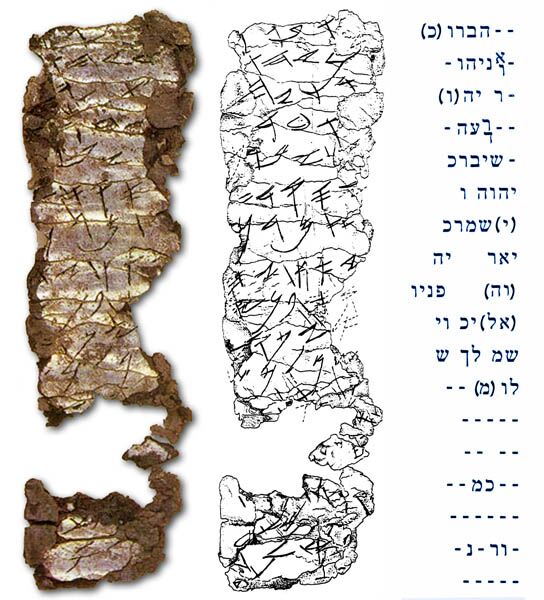

Ketef Hinnom and More Bullae

During archaeological excavations on the edge of the Valley of Hinnom, not far outside ancient Jerusalem’s walls, a large treasure cache was found in a burial tomb by the team of Prof. Gabriel Barkay. More than a thousand objects were found. Most significantly were two little metal scrolls, made of 99 percent pure silver. These scrolls were painstakingly opened in a laboratory, and were found to contain portions of Scripture, notably from Numbers 6:24-26 and Deuteronomy 7:9. These scrolls date to the seventh century b.c.e., making them the oldest biblical texts ever found.

Back within the walls of ancient Jerusalem, although it had expanded further north, the area including David’s palace had continued to serve as an important administration area for the Jerusalemite ruler. This was, in particular, shown by the discovery of the “House of Bullae.” This official house yielded up nearly 50 clay bullae seals that would have been used to seat official documents. Three bullae—found either in or around the house—are of note in particular. They date to the end of the seventh century to start of the sixth century b.c.e.

The first bulla reads as follows: “Belonging to Gemariah son of Shaphan.” This figure is described in the Bible as being an older scribe of King Jehoiakim (Jeremiah 36:10-12). After a scroll written by Jeremiah was read to the king, this Gemariah was one of three individuals who pleaded with the angry king not to burn it in a nearby hearth (to no avail—verses 22-25).

The two other bullae belonged to the princes alongside the following king, Zedekiah. The bullae read: “Belonging to Gedaliah son of Pashur” and “Belonging to Jehucal son of Shelemiah son of Shovi.” These two princes wanted to kill the Prophet Jeremiah, and were responsible for throwing him into a miry pit, into which he sank before being rescued by the Ethiopian Ebedmelech (Jeremiah 38:1-13—Jehucal is also mentioned in Jeremiah 37:3).

Jerusalem was destroyed around 586 b.c.e. King Zedekiah, who had tried to escape, saw his sons executed, then had his eyes put out and was taken prisoner to Babylon. The Babylonians utterly destroyed Jerusalem—as archaeological evidence confirms. The temple was not spared.

Rebuilding

It was less than 50 years later that the Babylonian Empire was overthrown by the Medo-Persian Empire. And under the benevolent rule of King Cyrus, a contingent of Jews returned from captivity to the Holy Land to rebuild the temple and the walls of Jerusalem (Ezra 1:1-3). It was around 445 b.c.e. that Nehemiah arrived on the scene as governor, constructing what is known as “Nehemiah’s Wall”—a major wall/gate/tower rebuilt all around Jerusalem, completed in only 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15). A section of this wall, dating to the Persian period, has been found. The appearance of the wall and a small tower that it connects to exhibits the “rushed” nature of construction.

With the temple reconstructed, as well as the city walls, Jerusalem continued to function as a Jewish city under foreign jurisdiction. However, under the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus Epiphanes, Jerusalem was sacked. Antiochus built a particularly tall fortress known as the Acra directly in the heart of Jerusalem, just south of the temple, designed to monitor Jewish activity. Long excavations at the Givati Parking Lot dig have finally uncovered this Hellenic fortress. The remnants are largely foundational, as according to Josephus, the Acra had been thoroughly destroyed as a result of the Maccabean rebellion.

During the later Roman rule, King Herod greatly rebuilt the temple, as a sign of goodwill to the Jewish people (a dubious gift, considering his murderous reign). The temple and associated buildings were grand and massive in size, but they didn’t stand long. Another Jewish rebellion against Roman rule brought a full quarter of Rome’s armies down on Judea. The struggle between the Jews and the Romans climaxed when Jerusalem was attacked, the walls broken down, and the temple complex burned and destroyed in c.e. 70. The historian Josephus witnessed and described in detail the thoroughness of the Roman destruction.

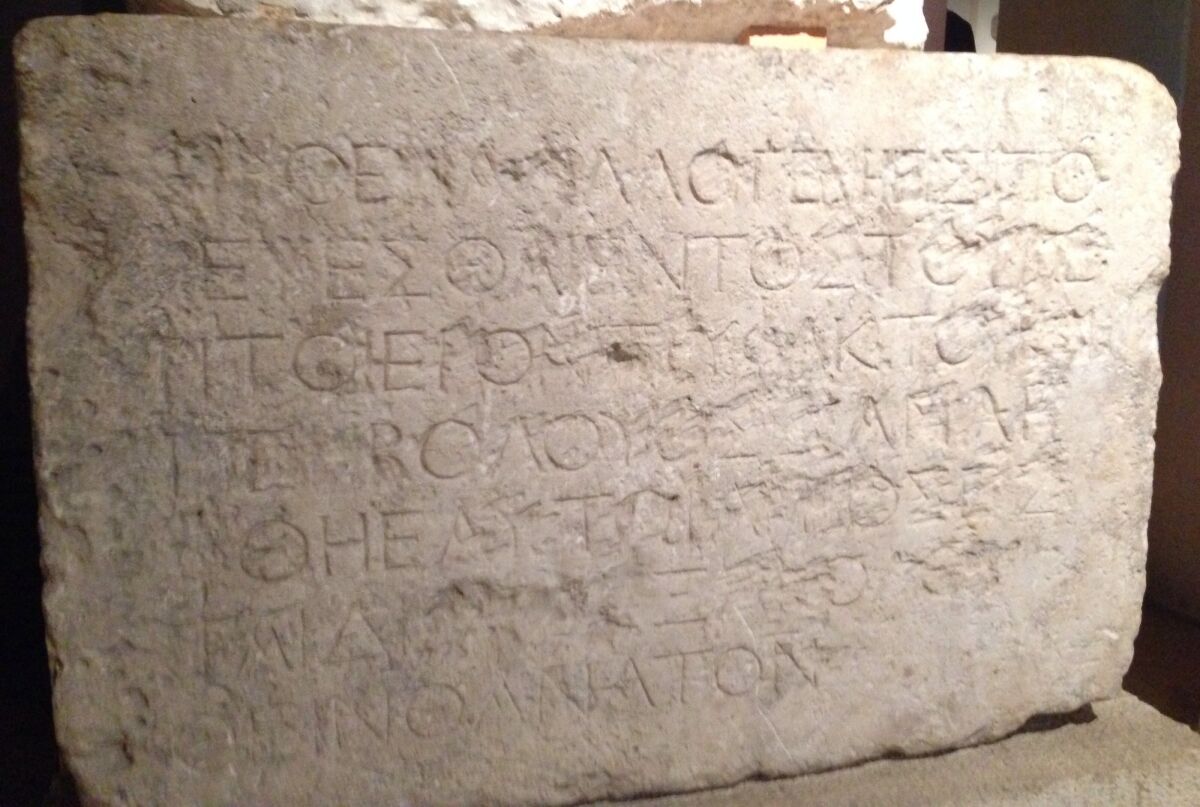

In spite of this utter destruction, some few identifiable stones from the second temple complex have been found—notably, the Temple Warning Inscriptions and the Trumpeting Stone.

The Temple Warning Inscriptions were large stones set into the walls of the temple precincts, bearing the following block of Greek text:

NO FOREIGNER IS TO GO BEYOND THE BALUSTRADE AND THE PLAZA OF THE TEMPLE ZONE. WHOEVER IS CAUGHT DOING SO WILL HAVE HIMSELF TO BLAME FOR HIS DEATH WHICH WILL FOLLOW.

Josephus confirmed the presence of these warning stones in his writings. Thus far, one complete stone block has been found, along with another partial block.

Another temple stone is a finely engraved piece with the broken-off Hebrew text, “To the place of trumpeting ….” This is believed to have come from the corner of one of the temple buildings, where a priest would blow a trumpet to signal the coming of the Sabbath. This practice is still carried out to this day—albeit not from the temple location.

Post-Roman Jerusalem to Today

Throughout the ensuing centuries, Jerusalem swung back and forth under the control of various kingdoms, repeatedly witnessing much bloodshed. During the early seventh century c.e., the Jews helped the Persians retake Jerusalem in return for being allowed to stay and rebuild the temple. Dating to this time period, Dr. Mazar uncovered a magnificent gold trove on Jerusalem’s Ophel mound. This trove included a large gold medallion embossed with the Jewish symbols of a menorah, shofar and Torah scroll. The medallion was probably intended to wrap around a large Torah scroll. A sizable hoard of coins and various other valuables were found, presumably to melt down in order to contribute to the building of a new temple/synagogue. However, for some reason, the goods were merely packaged up and left in the ground, where they were discovered some 1,400 years later. We know that those early-seventh-century Jews were soon driven out from Jerusalem by the massacring hand of Roman Emperor Heraclius—the hopeful residents who returned to build were forced to drop everything and run, perhaps taking time to burying what valuables they could before fleeing for their lives.

Rule over Jerusalem kept switching back and forth, particularly as a result of the rise of Islam and the Muslim-Catholic crusades. By the time World War i rolled around, the British forces took the city from then-Ottoman control. In 1948, the State of Israel was formally established in place of the British control, with Jerusalem set up as a “Special International Regime.”

A day after the United Nations passed the establishment, Arab armies swept in and attacked Israel. Jordan took full control of East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount and ancient biblical extent of the city. Yet when the surrounding Arab nations again declared war on Israel in 1967, the Jews pushed back and recaptured the entirety of Jerusalem. Jerusalem has continued to this day under Israeli rule—however, after the 1967 war, specific administration of the Temple Mount was allowed to the Jordanian-controlled Islamic Waqf, who maintains the mosques and other general buildings on the site.

And so we come to present-day Jerusalem. A Jerusalem whose ownership is still heavily disputed and warred over, as it has been for millennia. What cannot be disputed, however, is the solid archaeological history being revealed from the ground. Historical fact that astoundingly confirms the biblical account of Israel’s incredible capital city. A city where God—not a pharaoh, nor any other man or warring group—has placed His name forever.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer