A sensational discovery made international headlines in 2021: At the biblical site of Sodom—Tall el-Hammam—jaw-dropping evidence had been uncovered of some sort of fiery holocaust event that wiped out the city instantaneously, killing all inhabitants within half a second. Chemical analyses of remains from the site revealed temperatures briefly spiking to levels approaching that of the surface of the sun.

What was the cause? The researchers ascribed it to an “airburst event,” something like the mystery explosion in Tunguska, Russia, in 1908—when a meteor entering Earth’s atmosphere exploded above ground. There was no crater, but everything below was flattened and incinerated by a yield equivalent to hundreds of atomic bombs—something that could justifiably be described as “brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven,” to use biblical language (Genesis 19:24).

The discovery of some sort of fiery cataclysm at Tall el-Hammam was not without its detractors, however. Ironically, some of the most heated criticism came from scholars in the religious community itself, who argued that Tall el-Hammam could not be Sodom. They gave two reasons: The event occurred at the wrong time and in the wrong place—the destruction event occurred hundreds of years after the biblical event should have occurred and nowhere near the location in which it should have occurred.

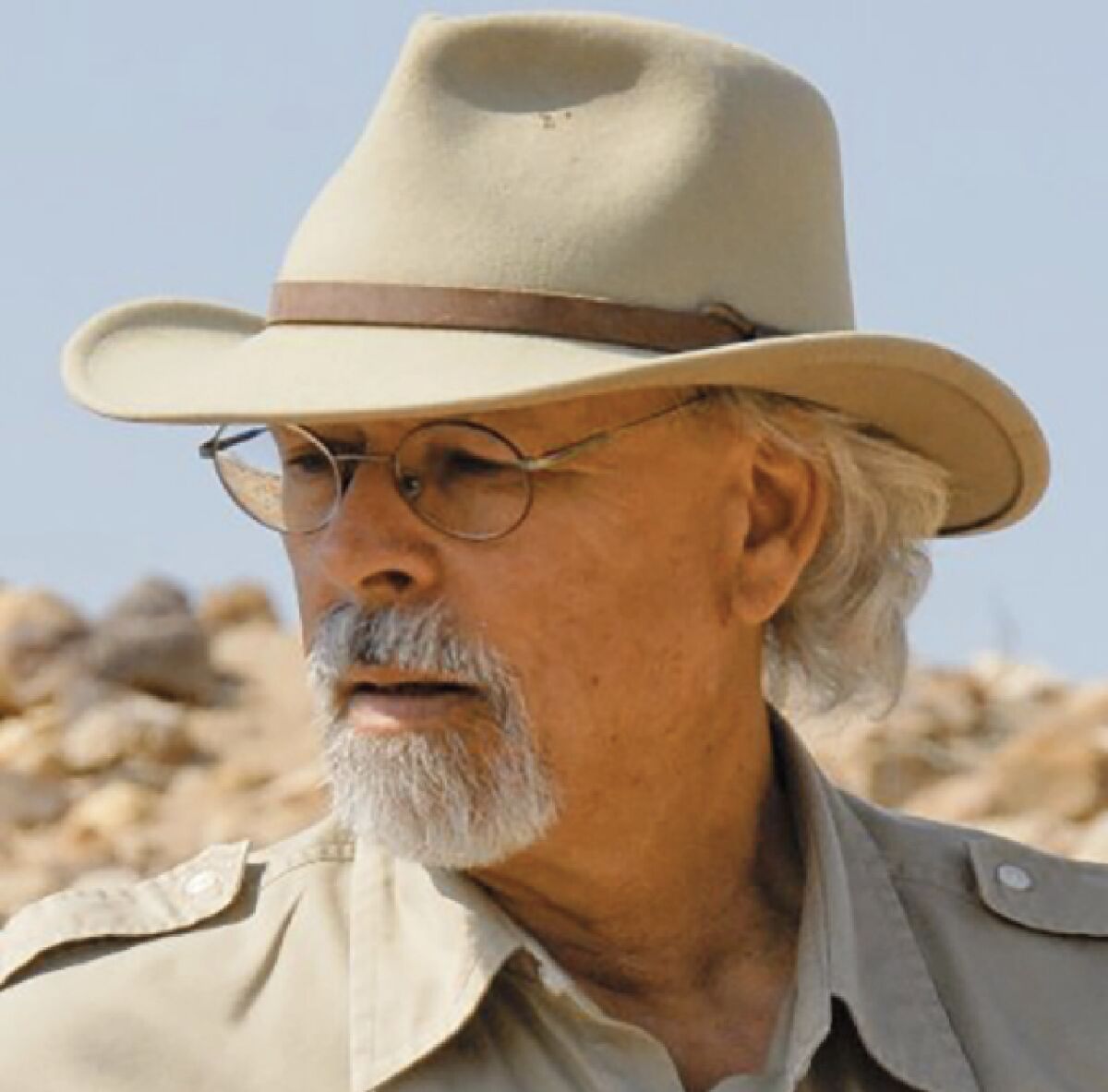

If Tall el-Hammam’s chief excavator, Dr. Steven Collins, is right about his findings—if his site is indeed Sodom and if this event is none other than the one of infamy described in Genesis 19—then he is responsible for one of the most astounding and sensational discoveries in the history of biblical archaeology.

But could Tall el-Hammam, on the northern end of the Dead Sea, be Sodom?

Southern Sodom?

Chances are, if you pull out a Bible map, it will place Sodom and its related “cities of the Plain” in the southeastern part of the Dead Sea region. For close to a century, the location of the city in this southern regional location has been taken almost for granted—and not without cause.

Ezekiel 16:46, for example, poetically describes Jerusalem: “[T]hine elder sister is Samaria, that dwelleth at thy left hand, she and her daughters; and thy younger sister, that dwelleth at thy right hand, is Sodom and her daughters.” The words “left hand” and “right hand” can sometimes be used to refer to north and south, directionally—indeed, this is how various translations render this passage. Samaria, for its part, certainly is north of Jerusalem; the inference, then, seems that Sodom must be located somewhere south of Jerusalem. Further, the famous sixth-century c.e. Byzantine Madaba mosaic map appears to place “Zoora”—Zoar, the location to which Lot and his daughters fled—at the southern end of the Dead Sea.

The inhospitable wastelands of the southern Dead Sea region are a picture of desolation. And embedded throughout the aggregate strata of the southwestern Dead Sea region are numerous miniature sulfur balls that can be pulled out of the sandy marl cliffs and even set on fire, for many calling to mind the picture of “fire and brimstone” that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah.

For these and other reasons, the ancient city of Bab edh-Dhra, an Early Bronze Age city on the southeastern shore of the Dead Sea, has popularly been identified as Sodom. And the site typically identified as Gomorrah is Numeira, situated roughly 20 kilometers further south.

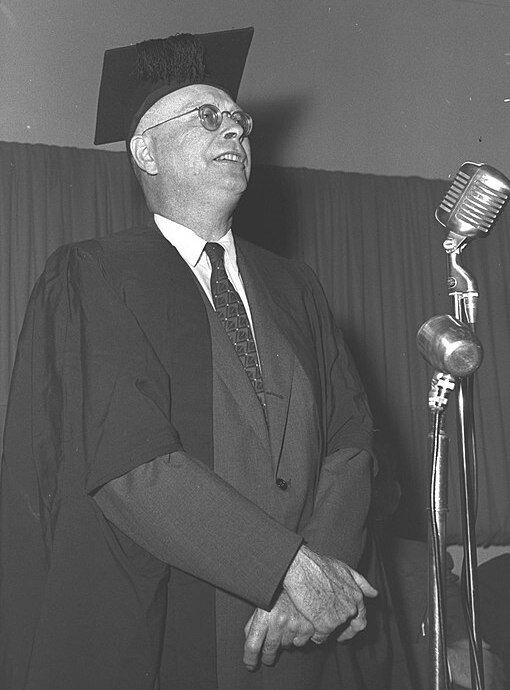

Chief credit for the discovery of Bab edh-Dhra goes to the late “father of biblical archaeology,” William F. Albright (1891–1971). Albright believed Sodom, Gomorrah and the other “cities of the Plain” were all located in this southern Dead Sea region. Actually, he opined that Bab edh-Dhra was not the city of Sodom but merely a subsidiary. Not having satisfied himself with evidence of the cities during a 1924 expedition, Albright instead noted the steadily rising water level of the Dead Sea at the time, wondering if the cities of infamy were submerged further out, just below the shoreline. “There is, accordingly, little likelihood that the exact sites of the original Zoar, of Sodom, or of Gomorrah will ever be recovered,” he concluded (“The Archaeological Results of an Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea,” 1924).

Nevertheless, following Albright’s general lead, his student Paul Lapp began excavating Bab edh-Dhra in 1965, followed by Lapp’s own student, Walter Rast, in the 1970s (at which time Numeira was discovered and also began to be excavated). Rast concluded that “these two Early Bronze iii cities of Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira may well be reflected in the stories of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Bible” (“Bronze Age Cities Along the Dead Sea,” 1987).

Granted, Bab edh-Dhra is relatively small; investigation of both it and Numeira revealed Early Bronze destruction layers, predating Abraham; further, their destructions did not seem to have occurred at the same time (there is also speculation that these cities were abandoned, not destroyed). The excavators of Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira themselves recognized the incongruities, thus proposing these sites only as the basis for an etiological legend of Sodom and Gomorrah—not as evidence of the actual events described in the Bible.

As for deposits of sulfur/bitumen, these are located more generally in the southwestern region of the Dead Sea, rather than the southeast; further, they are stratified within multiple sedimentary layers. Moreover, the Bible actually indicates the presence of such natural deposits even prior to the destruction of Sodom. Genesis 14:10 states that the “vale of Siddim was full of slime pits,” a word alternatively translated as “bitumen” or “tar” and a key component of which is sulfur.

Still, the presence of underground sulfur deposits in the region led southern proponents to tenuously hypothesize that the cause for the Genesis 19 destruction was some kind of earthquake along the Rift Valley fault line. This quake, so the theory goes, ignited an underground pocket of gases, which caused some sort of explosion that ejected burning matter into the air, subsequently raining down on the cities in question.

Various other explanations exist. For those holding to Albright’s initial hypothesis—that the cities were sunken at the southern end of the Dead Sea—this has been effectively disproved due to the alarming shrinkage of the Dead Sea since the 1960s, exposing much of this area without the slightest trace of civilization. Nonetheless, that Sodom was located to the far south was secure, and that Sodom was Bab edh-Dhra seemed more than likely—albeit on the basis that the Early Bronze dating for the site’s destruction must have been wrong.

One proponent of Bab edh-Dhra as biblical Sodom was Dr. Steven Collins.

Starting South—Looking North

“I was leading a study tour—I had Sodom and Gomorrah on the itinerary,” recalled Dr. Collins in a 2023 Socrates in the City interview with Eric Metaxas. “We were spending the night in Beersheba, in Israel, before we were going down to cross over to Eilat, to Aqaba. So I know the next day we’re going to head over to the traditional sites [of Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira]. And I thought, OK, I’m just going to brush up on the story. So I get the Bible out, and I read through the story. This was my very first moment—the aha moment, more or less.

“I read through … Genesis 13 through 19—and I got to the end of it, and I thought, I must be sleep-reading. … I woke myself up, sat up real tall, and read through it three more times. I read through that text four times, and when I got to the end of it, I closed the Bible and said to myself, Not only is there nothing in this text that would locate Sodom toward the south of the Dead Sea, everything clearly locates it north and east of the Dead Sea! And I couldn’t get past it.”

Collins was busy at the time with the excavations at Khirbet el-Maqatir. “But I thought, Someday, if life settles down and gets boring, I’m going to come back to this point. Because this is really bugging me. Why did I think it was toward the south? Why did everybody think it was toward the south?”

Collins’s research led him to discover a paradigm shift in the early 20th century. The southern location, it turned out, was not the “traditional” site at all. In fact, 19th-century geographers consistently placed Sodom and Gomorrah north and east of the Dead Sea. And continuing on into the 20th century, in spite of Albright’s influence, biblical geographers were still struggling with this notion of a southern Sodom.

“Back in the 19th century, virtually every single explorer scholar who went to that area … Thomson, Condor, Wilson, and so many others—they put Sodom at the northeast end of the Dead Sea,” Collins said. There was one exception—Edward R. Robinson—who posited the southern location and whose work influenced Albright. According to Collins, “Albright had so much influence.” Still, “it wasn’t that everybody went that way.”

“Let me give you an example. There’s a famous five-volume Bible encyclopedia, published by Zondervan. If you look up the article on Sodom, the writer is making a beautiful case, going through Genesis 13, for a northern Sodom. … And then he says, but I’m not an archaeologist, and W. F. Albright is the greatest archaeologist, and he puts Sodom at the south end of the Dead Sea, so I suppose I have to defer to him. And I’m going, NO, you don’t! And if you go to Zoar—which is a related town—just over to the ‘Z’ section of that encyclopedia, that writer makes a beautiful case for a northern Sodom, and sticks to his guns” (ibid).

Why did these early explorers and geographers, with near unanimity, locate Sodom in the north?

The Inheritance of Lot

The key is Genesis 13. “Genesis 13 is the verbal map,” observed Dr. Collins. “It is specifically written, consciously by the author to take the reader to the site of Sodom.”

Genesis 13 records the account of Abram and his nephew Lot parting ways because “the land was not able to bear them, that they might dwell together” (verse 6). Note that this conversation takes place in the region of “Bethel and Ai” (verses 3-4) in the central hill country, some 20 kilometers north of Jerusalem.

“And Abram said unto Lot: ‘Let there be no strife … separate thyself, I pray thee, from me; if thou wilt take the left hand, then I will go to the right; or it thou take the right hand, then I will go to the left’” (verses 8-9).

“And Lot lifted up his eyes, and beheld all the plain of the Jordan, that it was well watered every where, before the Lord destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt, as thou goest unto Zoar. So Lot chose him all the plain of the Jordan; and Lot journeyed east; and they separated themselves the one from the other. Abram dwelt in the land of Canaan, and Lot dwelt in the cities of the Plain, and moved his tent as far as Sodom” (verses 10-12).

From this location in the central hill country, Lot observed before him this great, expansive plain of the Jordan (referring exclusively to the Jordan River)—not of the Dead Sea (the southern plain of which would not have been visible from this point anyway). Choosing this plain of the Jordan, Lot subsequently traveled due east (not south), establishing himself on the far end of this plain—“as far as Sodom.”

There is further detail buried in the text. The word “plain” is the Hebrew kikkar (ככר), referring to a “disk” or something circular (and is a word used in modern Hebrew to refer to roundabouts). This southern end of the Jordan Valley, just north of the Dead Sea, just so happens to be a massive circular alluvial plain, one that would fit well with this use of the term kikkar.

Verse 10 likens this well-watered area to the “land of Egypt.” Here again, the imagery is a perfect match: The flowing (and overflowing) Jordan aptly parallels the key geographical feature of Egypt: the Nile River.

How did Albright reconcile his belief with the clear description in Genesis 13? He didn’t. “Albright never, ever, in any of his writings, does any textual analysis on Genesis 13:1-12. Never touches the geography,” marveled Collins.

Given the rather explicit description in Genesis 13, Collins argues that other less obvious, piecemeal biblical clues must be interpreted in light of it, rather than in spite of it. A case in point being Ezekiel 16:46: Rather than using a possible interpretation of “right” as “south,” thus upending the otherwise obvious Genesis 13 text, perhaps the word does simply refer to the “right hand” (as many translations render it), and technically could therefore include the “east.” (After all, in the words of Abram: “‘[I]f thou wilt take the right hand’ …. And Lot journeyed east”—Genesis 13:9, 11.) To that end, Ezekiel uses other words throughout when referring explicitly to the south, directionally (נגב ,דרום and תימנה; e.g. Ezekiel 20:46-47; 21:4; 40:2-45; 41:11; 42:12-18; 46:9; 47:1, 19; 48:10-33). The term used in Ezekiel 16:46, ימין, properly refers to the right hand (e.g. Ezekiel 21:22 and 39:3).

Genesis 13, of course, is not the only biblical evidence for the location of Lot’s settlement (though it is the most explicit). Another example is the settlement of his descendants, the Moabites and Ammonites—these two territorial entities clearly radiating out from this northeastern region of the Dead Sea, as the prescribed “possession” of the “children of Lot” (i.e. Deuteronomy 2:9, 19; see map, above).

As with Lot, then, we find ourselves standing in the central hill country, looking out east and beholding a well-watered, Nile-esque plain. We have our area. Now we must find our city. And one particular Bronze Age behemoth on the furthest side of the kikkar stands out above them all.

Tall el-Hammam

In the early 2000s, when Collins began searching resources for sites on the eastern side of the plain, he immediately ran into a problem: Archaeologically, it was a virtually blank map. Very few sites dotting the area had ever been documented on maps, let alone probed or excavated.

Eventually, Collins and his team found documentation of 14 specific sites, a handful of them more prominent than others, and one giant: Tall el-Hammam. It had been noted in a small 1991 book by Rami Khouri, The Antiquities of the Jordan Rift Valley, as the largest site in the entire Jordan Rift Valley. It turned out that the site had, in fact, been briefly probed in 1990; until a landmine blew the foot off one of the workers. This reinforced an already present sense of “bad juju of the site” among the locals, recalled Collins at a 2024 Cosmic Summit lecture: “You don’t go there.”

When Collins finally decided to investigate Tall el-Hammam, the enormity of the site astounded him. “I’ve seen every site in Israel. I know how big the sites are, and how they feel,” Collins said in his interview with Metaxas. “We pulled up to Tall el-Hammam. And looking at it, I almost didn’t realize what it was. It was so big, that it almost looked like part of the natural landscape.”

Not only is Tall el-Hammam the largest site in the Jordan Valley; the site turned out to be the largest continuously occupied Bronze Age city in the entire southern Levant. And for Collins, this was a perfect fit; he had already proposed, based on the biblical account alone, that Sodom must have been “the largest Bronze Age city north and east of the Dead Sea.”

Sodom, after all, is a key controlling site featured repeatedly in the patriarchal narratives. It is the first and key city in the sights of the Genesis 14 four-army Mesopotamian juggernaut. Sodom, along with neighboring Gomorrah, is the only regional city described as being plundered by these invading forces. Sodom is repeatedly referenced as a landmark location; it’s the only one of the “cities of the Plain” mentioned by itself in the biblical account; and the king of the city, Bera, is the only one who “has a voice,” who is quoted. Perhaps most notably, Sodom is actually included in the Genesis 10 “table of nations,” together with the likes of the great cities of Mesopotamia.

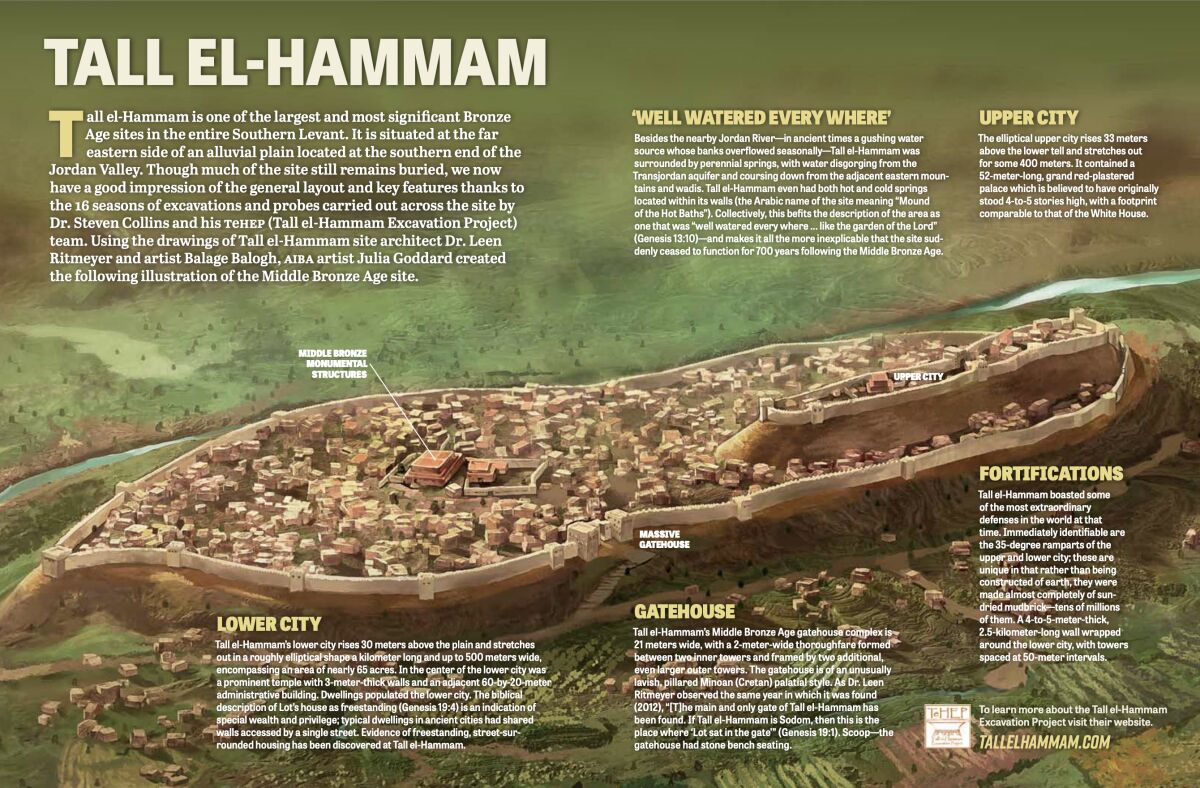

In 2005, Collins and his New Mexico-based team—led by Trinity Southwest University, together with Veritas International University, under the auspices of the Department of Antiquities of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan—began excavations. Today, after 16 seasons of excavations, we have a much clearer picture of this Bronze Age behemoth—and its sudden and shocking collapse.

Welcome to Sodom

Tall el-Hammam, including its adjacent suburbs outside the city walls, covered an enormous area of about 300 acres. Within this area, the elliptical walled lower city (“lower,” albeit still raised about 30 meters above the plain) stretched out more than a kilometer long, encircling nearly 65 acres. A massive angular, ramparted upper city rises up from the landscape like the Khetanna (for fellow Star Wars enthusiasts) by another 33 meters again. It contained a four-to-five-story royal palace complex, with a footprint “slightly larger than the White House,” said Collins in a 2023 interview with Sean McDowell.

“It wasn’t just one big site,” he went on. “It was one big site with a whole lot of towns and villages. So it’s really a major city-state. … You could put about six or seven Bab edh-Dhras inside the city wall of Tall el-Hammam. In fact, Bab edh-Dhra wouldn’t even be large enough to qualify as one of the bigger satellites of Tall el-Hammam.”

Tall el-Hammam’s city defenses were extraordinary. The city boasts the very first Middle Bronze ramparted fortification system in the entire Southern Levant. And its 35-degree rampart is the only such known fortification system made almost completely of sun-dried mudbricks—to the tune of “somewhere between 40 and 60 million” of them. “That’s expensive, it’s time consuming, and nobody else did it,” said Collins in his Cosmic Summit lecture. “Every other Middle Bronze fortification system after this is built of rammed earth.” Additional defenses included towers spaced at 50-meter intervals around the 2.5-kilometer city wall, and the walls themselves up to 5 meters in thickness.

That the city was lavish is an understatement. It had, quite literally, hot and cold running water, derived from two springs—one warm and one cold—located inside the city. (The site’s Arabic name means “Mound of the Hot Baths.”) Tall el-Hammam also boasted a large pillared city gate complex, constructed in the Minoan palatial style. This is Collins’s most prized architectural discovery: Archaeologists are always looking for the city gate complex, and Sodom’s is actually mentioned in the biblical account. Genesis 19:1 describes Lot sitting within the gate when he was met by the angels—and true to form, stone bench seating was found within the gatehouse. In the words of site architect Dr. Leen Ritmeyer in 2012, when the gatehouse was first discovered: “[T]he main and only gate of Tall el-Hammam has been found. If Tall el-Hammam is Sodom, then this is the place where ‘Lot sat in the gate’” (Discovering the City of Sodom).

Lot’s choice to move into the alluvial plain, and even establish himself with his own private house within the mighty city, would have seemed a no-brainer. “Now, he did respect Abraham—let’s not criticize Lot for being too greedy, and taking the best land—which, by the way, he did,” Collins told McDowell. “It is the best-watered agricultural land in the region. You don’t need rain. You have the Jordan River, plus you have a massive amount of water disgorging from the Transjordan aquifer into that area. Springs run out all over the place there to this day.”

The fact that this city was so perfectly situated and equipped to thrive is precisely what makes it all the more unusual that partway through the Middle Bronze Age, the continuous occupation of the idyllic city suddenly and violently stopped and would not resume again for another seven centuries.

This occupational gap was noticed by Collins and his team almost immediately. Archaeological excavation showed that the site exhibited no layers or remains from the subsequent Late Bronze Age. The same was true of the immediately surrounding sites.

What happened to this area?

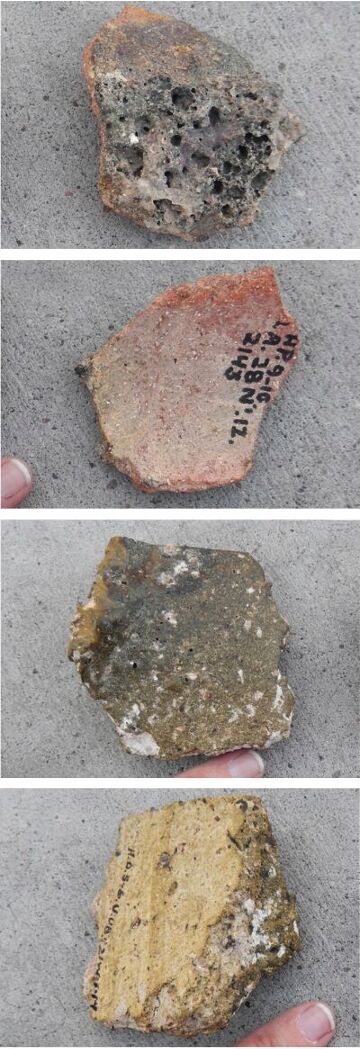

A clue came early on as the team cut a probe through first-millennium b.c.e. Iron Age remains, which immediately transitioned to an early second millennium b.c.e., 1.5-meter thick Middle Bronze ash- and bone-strewn destruction matrix. A volunteer plucked out of it a peculiar piece of pottery; it had a glassy surface and appeared to be glazed. Yet glazed pottery only emerges from the Islamic period onward—some 2,500 years later. What was it doing in a Middle Bronze level? Furthermore, the glassy surface had oozed beyond the break in the pottery, before solidifying—seemingly the product of some kind of brief, superhot flash-heating.

Collins tossed the piece up out of the probe to another member of the group—old-timer Gene Hall who, as chance would have it, had served as part of the World War ii Manhattan Project—the 1945 Trinity detonation in New Mexico of the world’s first atomic bomb. “This looks like trinitite,” Hall said, referring to the phenomenon of melted sand created by the atomic blast.

Collins brought the exemplar piece back with him to the New Mexico Technical University for analysis. Without explaining its provenance, he gave it to the lab analyst. “Nice piece of trinitite,” she said casually as she took it from him. “Where did you get it?”

Fire From Above

This “trinitite” was one of many signs of some kind of peculiar destruction event at Tall el-Hammam.

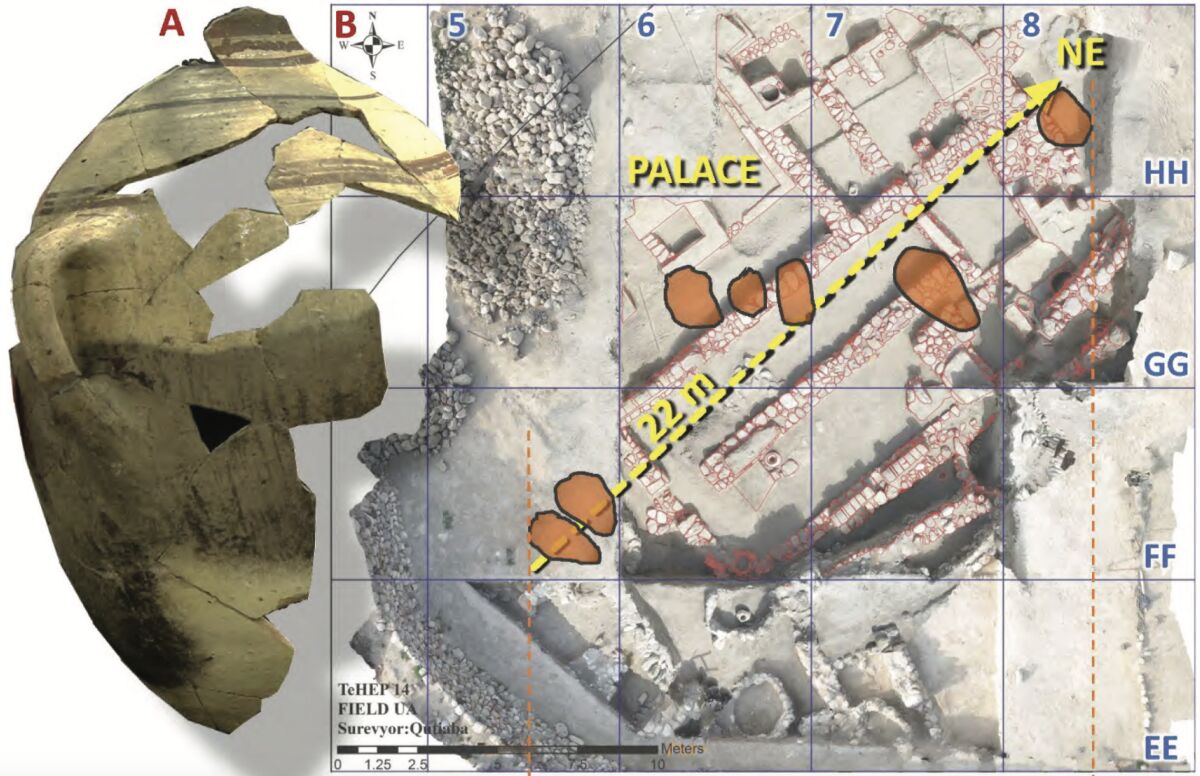

Destroyed pottery with surfaces melted into glass. Melted bricks, melted plaster. Massive quantities of ash. Scorched remains of people and vessels, not just strewn at random, but directionally—orientated in some sort of apparent “blast” direction. Mudbrick superstructures, up to 5 meters thick, sheared off at about waist height—the height of the rampart protecting them. The fragments of one particular vessel, which had a very unique design, were able to be traced—scattered along a 22-meter directional line across six walls and multiple rooms. And this destruction layer contained an unusually high salt content—“six times more concentrated than the Dead Sea.”

“There are skeletal remains that lie as they fell, wrenched and contorted. There’s human bone-scatter all through the final-day ash: human beings who blew apart before they fell,” write Collins and Dr. Latayne Scott in their 2012 publication Discovering the City of Sodom. “[H]ere, at Sodom, the rocks cry out a catastrophe.”

What could have caused such a disaster?

The answer was ultimately published in 2021 in the journal Nature Scientific Reports (part of the prestigious Nature portfolio), entitled “A Tunguska-Sized Airburst Destroyed Tall el-Hammam, a Middle Bronze Age City in the Jordan Valley Near the Dead Sea” (Bunch et al). The paper was the product of 14 authors, including airburst specialists (and as Dr. Collins often adds, most of them not persons of faith). The team presented the evidence that “a cosmic airburst destroyed Tall el-Hammam …. The proposed airburst was larger than the 1908 explosion over Tunguska, Russia, where a ~50-meter-wide bolide [meteor] detonated with ~1000x more energy than the Hiroshima atomic bomb.”

The article documented the telltale signs at the site of an airburst event, noting that the destruction stratum contained concentrations of shocked quartz, diamonoids, iron- and silicon-rich spherules, and trace remains of melted platinum, nickel, gold, silver, zircon, chromite, quartz and iridium (the latter of which has a melting point of 2,500 degrees Celsius, or 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit). Taken together, these constitute textbook signs of extraterrestrial interference—“commonly accepted cosmic impact indicators.”

Airburst events are a known phenomenon in Earth’s history, which is why such data can be comparatively measured. But no such post-Sodom event is known to have occurred within a populated area, exploding at such a low altitude to cause this kind of regional extinction-level devastation.

Elements aside, the more macabre remains are the human. One example is a pair of prone skeletal legs and feet—everything from the mid-thigh up having simply sheared away—the “hyper-flexed toes” of which are “consistent with either perimortem or postmortem exposure to high temperatures.” Another skeleton “was found buried in a crouching position with the hands raised to the face, a posture commonly adopted for protecting the head, as occurred during the volcanic eruption at Pompeii.”

“Based on the distribution of human bones on the upper and lower tall [mound], we propose that the force of a high- temperature, debris-laden, high-velocity blast wave from an airburst/impact 1) incinerated and flayed their exposed flesh, 2) decapitated and dismembered some individuals, 3) shattered many bones into mostly centimeter-sized fragments, 4) scattered their bones across several meters, 5) buried the bones in the destruction layer, and 6) charred or disintegrated any bones that were still exposed,” write the authors.

Death would have been instantaneous, killing all living things in the area within a split second. Sudden destruction—and even this is reflected in the biblical account. Lamentations 4:6 states that Sodom was “overthrown as in a moment”—in the blink of an eye.

As for the continuing desolation of this and surrounding sites, the authors credit it to the hyper-salinity in the destruction layer created by the blast wave over this Dead Sea zone, essentially coating the cities and wider region in concentrated salt—making it impossible for crops to grow until rainwater had sufficiently washed enough of it out centuries later. During this period of desolation, certain evidence from the biblical and Egyptian texts shows that the “ensuing name of the area became Abel, the ‘mourning grounds’” (see Sidebar 2 at the end of the article).

Certainly, this is the sense given by Moses in describing the view from the mountains of this area, “which looks down on the wasteland” (Numbers 21:20; New King James Version).

Fallout

Collins, for his part, declined to coauthor the paper. He also recommended that the authors make no link with the biblical account. Yet such an obvious connection could not at least be mentioned; as such, the authors made passing allusion to the fact that the destruction event “might be the source of the written version of Sodom in Genesis.”

Chaos ensued.

Collins explained the drama in his interview with McDowell. “It’s the most accessed scientific paper in the history of scientific papers, that they know of … this one just went crazy. And because of that, there was a lot of pushback. … The anti-Bible folks went ballistic and really pushed back—made all kinds of accusations that photographs were faked, this was faked, that was faked. Why would these guys do that? Nobody bothered to answer that. Why would you fake any of this?

“It went through a first peer review, of course, to get published initially. Then, because of some of the accusations that were made, it went through a second peer review, and remained published—it passed—and now it has gone through a third peer review on the basis of some additional stuff, and now the editors I think have basically thrown up their hands and said, ‘Enough is enough, the more you guys gripe, the more you guys try to overturn this paper, the more is demonstrated that it’s actually factual.’” Collins also noted that one of the chief antagonists was an airburst specialist whom he had turned to initially to do the research: The individual refused from the outset on the basis of any possible link of the event to the biblical account.

Accompanying the secular fallout was a degree of fallout from among the religious community. While the news was received with interest by the general public, there was significant pushback from within biblical scholarship, based partly on the location and partly on the date of the destruction (see Sidebar 1, below).

At this point, however, Collins believes such misgivings about the identity of the site should be laid to rest. “This is Sodom,” he asserts. “If it isn’t, then by all means, biblically, tell us what it is.” “That’s a good question,” replied McDowell, who has also featured the southern theory on his channel. A second major paper has now been published—one Collins did elect to coauthor—building on the foundation of the former, entitled “Modeling How a Powerful Airburst Destroyed Tall el-Hammam, a Middle Bronze Age City Near the Dead Sea” (Silvia et al).

“It’s nothing short of a cosmic event,” Collins told McDowell of the destruction wrought at his site. “Some [southern proponents] suggest that maybe some hydrocarbon gas belched out of the ground as a result of an earthquake, flew up in the air, caught on fire and landed on the cities. … That would be a terrestrial event. That would be the ground belching fire, not the sky. The text clearly says, fire and burning stone—brimstone, if you like—from yhwh out of the heavens. It’s coming out of the cosmos; it’s not a terrestrial event. And that’s exactly what we have.”

“I think it’s a done deal,” concluded Collins, regarding the identity of his site. “I don’t think it’s a theory anymore. I just think it’s a fact.”

As someone sympathetic toward the southern view, I have to agree: The infamous sin city and its destruction, by now, is as good as identified—no longer a theory, nor a merely mythical biblical tale, but fact.

Sidebar 1: Dating Sodom’s Destruction

The date of Tall el-Hammam’s destruction has been a major point of contention. The site has been dated to the Middle Bronze ii period, within the early-mid part of the second millennium b.c.e. Generally, the terminal layer is described as dating based on pottery to circa 1750–1650 b.c.e. More recently, carbon-dating indicates a “93.1 percent between 1773–1627 b.c.e.” (lecture, “Is This the True Location of Biblical Sodom?”, 2024). Generally speaking, Tall el-Hammam was destroyed within the 18th to 17th century b.c.e.

This general time frame, well within the first half of the second millennium b.c.e., is the time frame broadly attributed to the patriarch Abraham in Jewish and Islamic communities, as well as in many Christian communities. A relatively popular position within some circles, however, says that Abraham was on the scene at the end of the third millennium b.c.e.—several centuries earlier.

Most of this chronological tension arises from the debate about the length of the Israelite sojourn in Egypt. Exodus 12:40 reads: “Now the time that the children of Israel dwelt in Egypt was four hundred and thirty years.” A fairly common conservative view holds to an early Exodus occurring circa 1446 b.c.e., derived 480 years prior to the building of Solomon’s temple in 967 b.c.e. (1 Kings 6:1); adding 430 years for the descent of Jacob’s family into Egypt takes us back to circa 1876 b.c.e., and counting backward another 290 years takes us back to a birth of Abraham, circa 2166 b.c.e. This puts the destruction of Tall el-Hammam centuries after his death.

There is an alternative, popular late-date Exodus view—the 13th-century view—which would down-date Abraham by between one and a half to two centuries. Yet even this would not be sufficient to put the events at Tall el-Hammam within Abraham’s lifetime. For that matter, Collins himself holds to what could be called an early Exodus view (albeit slightly later, in the ballpark of 1400 b.c.e., in closer accordance with the lower Septuagint chronology for 1 Kings 6:1—for more on this, see the following articles here and here).

The primary contention, then, has to do with the length of the Israelite sojourn in Egypt. Were the Israelites really in Egypt for 430 years, from the time of Jacob’s descent to the Exodus?

This is a significant topic of debate, explained in our article “When Was the Age of the Patriarchs?” In it, we make the case for a roughly two-century-long sojourn as the correct interpretation reflected by the biblical data. In short, ironically, this standard Jewish understanding is reflected best in the New Testament: In Galatians 3:17-18, Paul notes the 430 years as spanning from God’s covenant with Abraham to the year of the Exodus and the giving of the law at Mount Sinai.

There are different opinions as to when this covenant is anchored in Abraham’s life. Nonetheless, even with an early (mid-late 15th century) Exodus date, this would still put Abraham on the scene into the 18th century b.c.e.—near enough in the ballpark to the earliest dating for the destruction of Tall el-Hammam.

Questions remain, in both dating and interpretation—but for an event nearly 4,000 years ago, the time frames are remarkably close (and certainly for that matter closer to Abraham than the dating of Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira).

And that this general period—the Middle Bronze ii (19th–17th century b.c.e.)—is the correct one for Abraham is best reflected in the biblical cities mentioned in relation to him, such as Jerusalem, Hebron, Dan, Shechem and Damascus. These are cities that we now know archaeologically emerged during this specific period.

Sidebar 2: Is Sodom Mentioned Only in the Bible?

One argument against the historicity of Sodom and its destruction is that it is a city known only from the biblical text. “People have been asking me for 20 years, If Sodom was such a big deal, and this event was such a big deal, how come we never hear of it from the other ancient records outside the Bible? Never say never,” Dr. Steven Collins said in his 2024 Cosmic Summit lecture. He then boldly announced: “We have found Sodom in the Egyptian records”—the publication of which is forthcoming.

Collins credited the research that led to this discovery to “my good friend Anson Rainey,” one of Israel’s most highly regarded biblical geographers and linguists (who died in 2011). “I’m looking at his excursus on the Egyptian execration texts—these are from the latter part of the Middle Bronze Age, and they are from the Theban pharaohs in the south, cursing all of these Canaanites,” Collins said. “[Rainey] put all of these cities mentioned in the execration texts on a map. I looked at the map. There’s a site called Šutu. That could be rendered a couple of ways from Egyptian. It could be rendered Šutu; it could also be rendered Sudu. And I looked at his map, and where does he put Šutu? Right on top of Tall el-Hammam.

“And then I realized that there is the objective case shift from Egyptian into any of the Semitic languages in which you add the letter m, becoming Šutum or Sudum, which is exactly what we find in the Old Testament. So in the Middle Bronze Age Egyptian execration texts, the location of our site is called Šutu or Sudum.” But that’s not all.

In the ensuing centuries, the Egyptian name for the area changed. “After the Middle Bronze Age, the name of the site changed to Abel. This is on the Egyptian map list from the 18th and 19th Dynasties, well documented,” Collins continued. “The name of our site, of that area that we’re in, went from Šutu to Abel. What does the Egyptian word abel mean? It’s also recorded in the Hebrew. It means to mourn a catastrophe. From Šutu to Abel—what happened, to take us from one to the other? There was an event.”