An incredible location in its own right, Jericho claims the record for being the lowest city in the world (244 meters—800 feet—below sea level). It is also regarded as the most ancient city ever discovered. Because of the biblical importance of this city, Jericho was second only after Jerusalem in order of excavation by archaeologists, with digs beginning in the mid-1800s. The archaeology of the site, while still much debated and argued, is fascinating.

Before the Israelites

Historically, Jericho was also known as the “city of palm trees” (Deuteronomy 34:3, 2 Chronicles 28:15). It was a well-watered city, with a large nearby spring (believed to be the same spring whose water was turned from bitter to sweet through the Prophet Elisha—2 Kings 2:18-22). One theory for the origin of the city name “Jericho” is its close link to the word for “moon.” Indeed, Jericho was anciently a center for worship of the moon god.

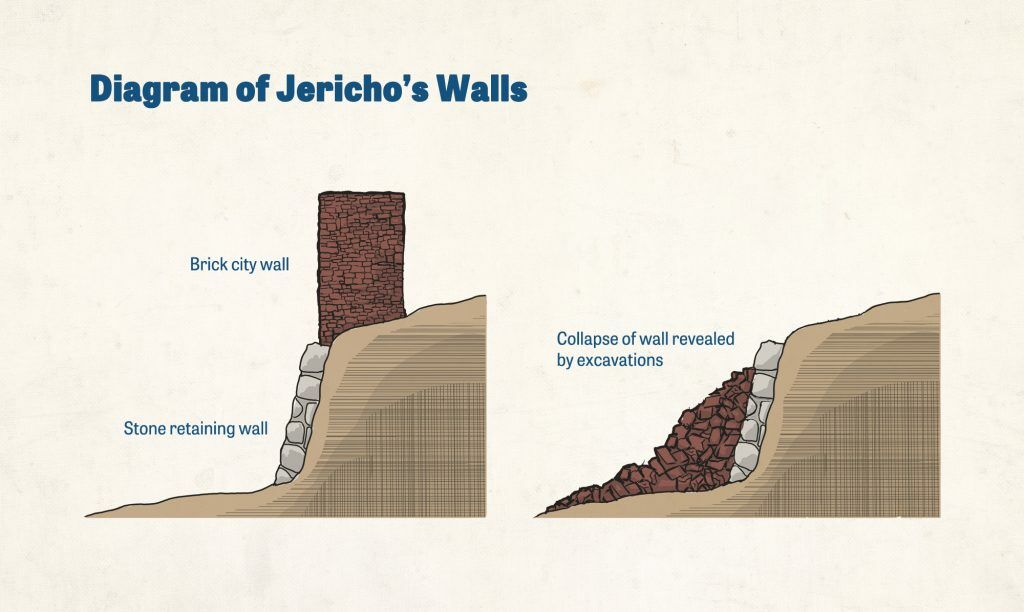

Well before the Israelites arrived, the city was strongly built and fortified. A massive ancient cylindrical tower was found at the site, believed to be one of the oldest towers known. By the time the Israelites arrived at Jericho, the city had already been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times, as the archaeological record shows. The city reached its height of power around 2000 b.c.e., during the Middle Bronze Age. It had powerful defenses, including strong walls of stone and brick. A stone retaining wall propped up the raised tel mound of the city, standing at around five meters high, atop of which was a brick wall around two meters thick and four meters tall.

The Controversy

Before describing the arrival of the Israelites, we must first briefly examine the controversy regarding the archaeological site of Jericho. One of its chief excavators was British archaeologist John Garstang. His excavations during the 1930s confirmed to him that a significant destruction of Jericho had occurred around 1400 b.c.e. (around the time the Israelites entered the Promised Land). However, the next (and primary) archaeologist to excavate Jericho, the famous and well-respected Kathleen Kenyon, disagreed. Based on her excavations, she believed that the destruction of Jericho must have happened around 1550 b.c.e.—150 years before the Israelites would have arrived. While the evidence of the type of destruction that happened matched perfectly with the biblical account, Kenyon claimed that it could not possibly have occurred at the time the Israelites were in the land.

Since Kenyon’s excavations, an intense debate has ensued between those following Kenyon’s mainstream 1550 b.c.e. dating and those adhering to a 1400 b.c.e. collapse and thus connection with the Israelites.

Kenyon believed Jericho’s destruction must have happened much earlier because of a lack of certain types of later-period pottery at the site that one would normally expect to find during the Late Bronze Age (up to and including 1400 b.c.e.—the time of the Israelites in the Promised Land). She especially noted a lack of the later-imported Cypriot pottery at the site, which in other locations was commonly found by the time the Israelites had entered Canaan. Furthermore, radiocarbon dating of samples from the site put the destruction at or around 1550 b.c.e.

Archaeologist Bryant Wood is Kenyon’s chief objector on the dating of the fall of Jericho. He puts forward a detailed explanation here as to why he believes in a 1400 b.c.e. destruction. Firstly, he states the problem that Kenyon’s conclusions were drawn from what wasn’t found at the site. He wrote:

Kenyon based her conclusions on a very limited excavation area—two 26-foot-by-26-foot squares. An argument from silence is always problematic, but Kenyon’s argument is especially poorly founded. She based her dating on the fact that she failed to find expensive, imported pottery in a small excavation area in an impoverished part of a city located far from major trade routes!

Secondly, upon closer appraisal of the pottery at Jericho, he states that the “missing” Late Bronze Age pottery (and perhaps even some examples of the Cypriot pottery) were present after all—and were simply overlooked. And regarding the radiocarbon dating, Wood points out the consistent errors that occur in calibration, which in many cases are known to give much earlier dates to known later historical events.

It is up to the reader to study and decide. I believe Wood’s explanation is credible, and the archaeological synthesis with the biblical account of the city’s destruction, as will be shown below, is too strong of a proof to be anything other than what occurred during the time of Joshua.

Rahab’s House

Back to the biblical account. The Bible story of Jericho’s defeat is well known. Before the Israelites crossed the Jordan River into the Promised Land, Joshua sent two spies to scout out Jericho and the surrounding territory. The spies entered the city, and stayed in a lodge belonging to the harlot Rahab. During their stay, the king became suspicious of their presence, and requested the men be brought to him. Rahab, however, hid the spies on her rooftop among stalks of flax, before lowering them from her window in order for them to escape from the city. The spies then promised Rahab that she and her family would be spared from the imminent destruction of the city.

There are a few interesting archaeological features that can be gleaned from this story. Firstly, we realize that Rahab had a traditional flat-topped accessible roof to her house. Secondly, and more importantly, her house was literally on, or part of, the city wall. “Then she let them down by a cord through the window: for her house was upon the town wall, and she dwelt upon the wall” (Joshua 2:15; King James Version). This was actually quite a common method of ancient building. City walls would be “hollow,” and citizens could live inside the walls. This would make the most of room inside the city, as well as limiting the number of additional walls to build for individual houses. In the event of a siege, the hollow walls could then be filled in with rubble to create one solid, massive reinforced wall. Added to the description of Rahab’s accessible roof area, this means that Rahab’s wall-house constituted the top parapet of the wall, that soldiers could stand atop to look out over advancing enemies.

The Collapsing Walls

The Bible is clear on exactly how Jericho’s walls were breached. God commanded the Israelites to walk the circumference of Jericho once a day, for six days, in procession. On the seventh day, they were to compass the city seven times, before crying out in a loud voice, together with shofars.

“So the people shouted when the priests blew with the trumpet: and it came to pass, when the people heard the sound of the trumpet, and the people shouted with a great shout, that the wall fell down flat, so that the people went up into the city, every man straight before him, and they took the city” (Joshua 6:20; kjv).

Archaeological excavations from this period of destruction show that the outer brick wall had in fact collapsed outwards, falling “flat” around the city base. Normally, a besieged city’s wall would be demolished inwards by invaders attempting to enter. These walls clearly collapsed outwards. Added to that, the architectural style of Jericho’s walls makes this event even more interesting. Remember the above description of the tall stone retaining wall around the raised base of Jericho, atop of which was the brick city wall? While the stone retaining wall remained in place, it was the main brick wall placed above it, enclosing the city, which fell down against the lower retaining wall—thus creating a perfect ramp up the retaining wall and into the open city. Thus, the Israelites “went up into the city.”

The incredible collapse of the walls, as proven by archaeology carried out at Jericho, isn’t the only interesting biblical parallel found at the site.

“And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city … And they burnt the city with fire, and all that was therein: only the silver, and the gold, and the vessels of brass and of iron, they put into the treasury of the house of the Lord” (Joshua 6:21, 24).

The archaeological evidence at Jericho clearly shows utter destruction of the site by fire. What was burned is especially interesting. The Bible shows Jericho’s destruction occurred during the spring harvest season (Joshua 5:10-12). Excavations have shown great quantities of the harvested grain in large containers at Jericho—burnt to a crisp. This is unusual; grain was a much-valued commodity. Ordinarily, city conquerors would salvage foodstuffs such as this before setting the city alight. Not the Israelites. They were instructed not to take anything for themselves (Joshua 6:17-19—only treasures dedicated to God were salvaged). As such, even the valuable grain stores were left behind to be consumed by fire.

The walls, the destruction, the fire, even the harvest season—the archaeology shows an amazing parallel account with the biblical record.

And yet the general destruction of Jericho wasn’t enough for the pagan site. Joshua also pronounced a curse on the location (verse 26; kjv):

And Joshua adjured them at that time, saying, Cursed be the man before the Lord, that riseth up and buildeth this city Jericho: he shall lay the foundation thereof in his firstborn, and in his youngest son shall he set up the gates of it.

Thus it is no surprise that the archaeological evidence shows this site has since, for the most part, remained eerily quiet to the present day. Of course, the immediately surrounding areas have been heavily and repeatedly settled. And there has been evidence of more sparse development of parts directly on the tel. But not in terms of greatly reestablishing the city, refortifying it to its state of former glory. With a certain exception—more on that further down.

King Eglon’s Interlude

Early during the time of the judges, Israel had descended into a state of rebellion. As a result, God sent the Moabite King Eglon and the armies of Ammon and Amalek to enslave the Israelites. Eglon “possessed the city of palm-trees”—or Jericho—and ruled over the people for 18 years (Judges 3:12-14).

During excavations conducted by Garstang, a small palatial building was found on Tel Jericho, which was dated to this period of the judges (again, a dating that is contested). It is believed that someone wealthy dwelt there, and only for a brief period of time. This provides a tantalizing link to King Eglon’s “summer parlour” (described in Judges 3:15-26), from which he briefly lived, where he was killed by the Benjamite Ehud. The Bible records the gory demise of the particularly obese king (verses 21-23; kjv):

And Ehud put forth his left hand, and took the dagger from his right thigh, and thrust it into his belly: And the haft [hilt] also went in after the blade; and the fat closed upon the blade, so that he could not draw the dagger out of his belly; and the dirt came out. Then Ehud went forth through the porch, and shut the doors of the parlour upon him, and locked them.

The Jericho Curse

As stated above, archaeology does indicate that there have been sporadic instances of living on Tel Jericho itself since the time of Joshua. Yet it was the surrounding areas that were heavily inhabited. There are several biblical references to establishments in the wider Jericho area. King David instructed his servants to remain in the area of Jericho until their beards had grown out, after a foreign king had half-shorn and humiliated them (2 Samuel 10:3-5). Elijah had a school of the prophets stationed there (2 Kings 2:4-5)—and with their training they must have been especially aware of Joshua’s curse on the mound proper. But for the most part the mound itself remained abandoned and unfortified.

There was an exception. One man ignored the curse and began rebuilding the city directly atop the Jericho mound.

King Ahab’s reign over the northern kingdom of Israel was a time of blatant departure into idolatrous worship. “Ahab did more to provoke the Lord God of Israel to anger than all the kings of Israel that were before him” (1 Kings 16:33; kjv). During his rule the Israelites became comfortable in their rebellion, not fearing consequences. And then tragedy struck.

Ignoring the curse on Jericho, a man of Bethel named Hiel decided he would rebuild the city. And his efforts played out exactly as Joshua warned. While laying the foundation of the city, his firstborn child died. By the time he added the gates, his youngest child was dead. 1 Kings 16:34 implies that if Hiel did have more than two children, they would have died sometime in between. Hiel paid a heavy price for his carelessness to the Jericho curse.

Jericho Today

While the old mound of Jericho still remains scarred and uninhabited today, communities continue to live in the surrounding area. Jericho was recaptured by Israel from Jordan during the 1967 Six-Day War, together with the rest of the West Bank. With the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1994, however, control of Jericho was formally handed over to the Palestinian Authority under Yasser Arafat. Today, unfortunately, Jewish travel to Jericho is prohibited under Israeli law. Unless given a special army escort, only non-Israeli tourists are permitted to enter and visit the modern town and ancient site.

And so the old tel location of Jericho, cursed from the time of Joshua, lies dormant. The area stands to this day, through biblical history and archaeological discovery, as a monument to the powerful God who through an abundance of miracles brought the Israelites across the Jordan River into Canaan—and helped them overcome this first city located within the Promised Land.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer