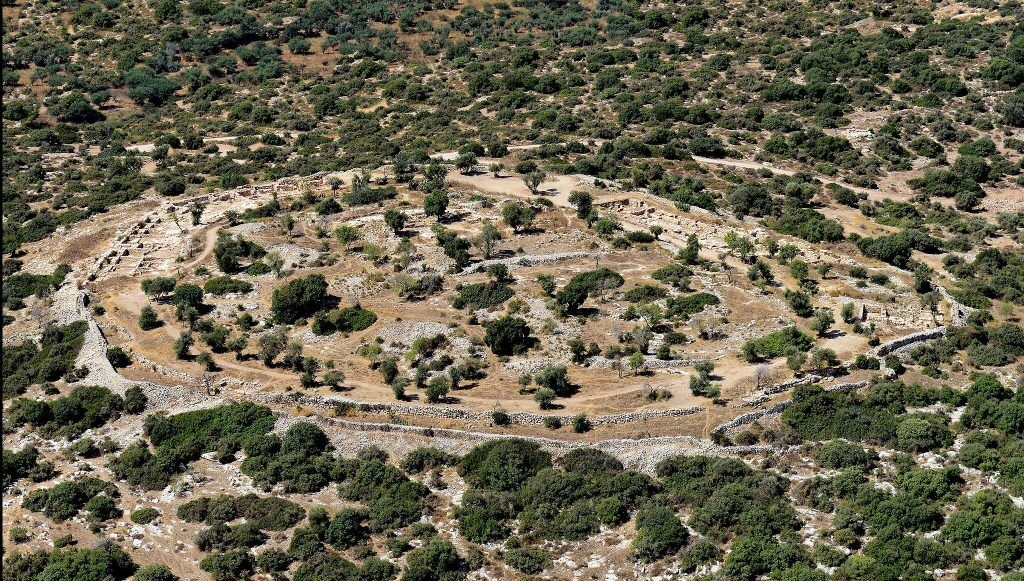

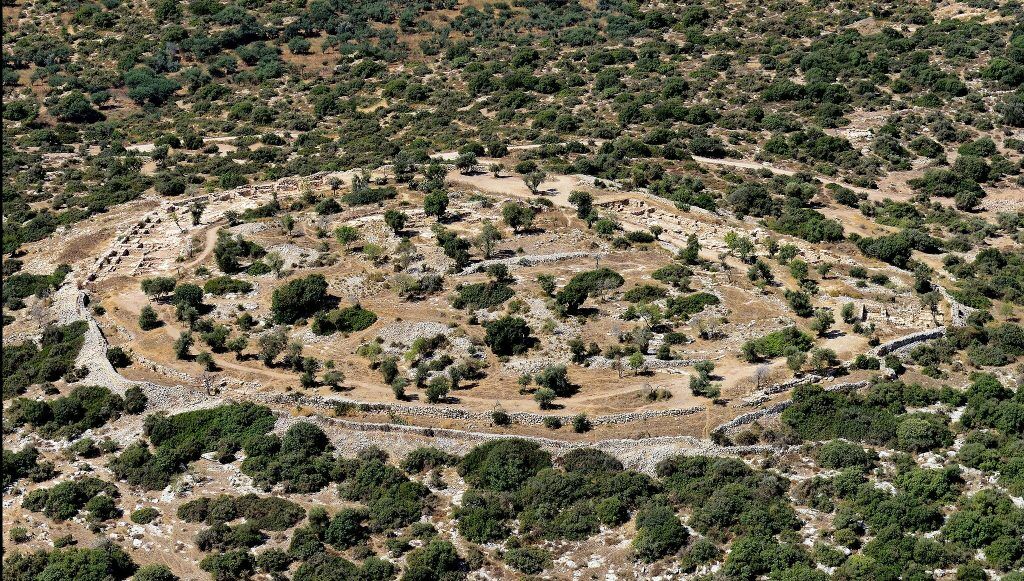

Khirbet Qeiyafa is an extremely unique site in Israel. Unlike the other ancient Israelite cities covered in this series, this fortress site is relatively “easy” for archaeologists. That is to say, because it only briefly functioned as a city. It has only one principle layer of settlement (contrasted against Megiddo’s 26). It has only one layer of destruction. Everything on the site, essentially, is from the same time frame (aside from some much later and less-extensive additions).

Let’s establish one thing from the start: Khirbet Qeiyafa has not definitely been linked with a specific city in the Bible (hence the commonly used Arabic name). There are a few options that are on the table, as this article will describe. However, this special site, inhabited perhaps for only a short number of decades, does go a long way in verifying the context of the earliest (and much debated) years of the Kingdom of Israel, during the time of King David himself.

Philistine or Israelite?

Khirbet Qeiyafa is a large fortified hill mound about 30 kilometers (20 miles) southwest of Jerusalem. It stood directly between Israelite and Philistine land. It overlooks the Elah Valley, where the battle between David and Goliath occurred (1 Samuel 17:2). This fortress was established in a contested area. So who did it belong to: the Philistines, the Israelites or another culture?

Attempting to prove the ownership of this fortress has yielded some interesting information. Biblical minimalists say that, at the time this structure was built, Israel was too small to establish such a monumental fortress. Thus, they assert that Khirbet Qeiyafa was built by Philistines or some other culture—but certainly not Israel. Bible traditionalists say that Israel was indeed capable of building a structure such as this, and that the remaining question is whether this site served the Israelites or the Philistines.

Archaeologists have found over 3,000 animal bones within Khirbet Qeiyafa. After the bones returned from analysis, an interesting revelation emerged: None of them were from pigs. In Philistine and Canaanite cities, pig bones are commonly found. Pigs were used as food and probably as sacrifices as well. In this aspect, Khirbet Qeiyafa stands apart.

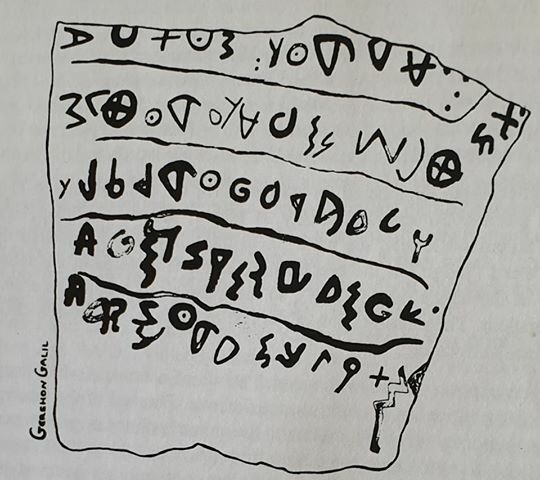

Linguistic evidence of the site’s owners included a large shard of pottery covered in ancient Hebrew script. Structural evidence includes the fact that houses at Khirbet Qeiyafa were built abutting the city wall in a plan not found in Philistines or Canaanites cities, but unique to Judean cities. The site also has no central location of cult worship. Other artifact-based evidence includes the lack of idols present at the site: Graven images are common to Philistine and Canaanite cities.

A number of olive pits were also excavated from Khirbet Qeiyafa and carbon-14 dated. The analysis returned a date range of 1020 to 980 b.c.e., directly within the timeframe of King Saul and King David. (As a rough estimate, Saul’s reign lasted from 1050 to 1010 b.c.e., David’s from 1010 to 970 b.c.e., and Solomon’s from 970 to 930 b.c.e.)

The majority of evidence at Khirbet Qeiyafa points to it being an Israelite site.

Dating to King David?

In the light of all this evidence, why the contention that Khirbet Qeiyafa was not Israelite? The reason is because of its dating. The city is dated by pottery and carbon-14 analysis to the 11th century to early 10th century b.c.e. This means the site was built around the time of King David, and possibly even the time of King Saul. Bible minimalists have already staked out their claim that David was just a tribal chieftain with minimal control over a small area of Israel. That means that if you find a major city like Khirbet Qeiyafa dating to King David’s time, you must conclude that it was built by some other nation. Hebrew pottery, Hebrew building methods, missing pig bones, missing cult centers and missing idols notwithstanding, Khirbet Qeiyafa was not Israelite, because Israel could not have had the national unity and infrastructure to necessitate or build this large fortress. How do the biblical minimalists know? Because they believe David was not the great king the Bible claims he was.

And yet the archaeological evidence, corresponding with the biblical record, states just the opposite. This was a powerful early fortress in the Kingdom of Israel guarding the nearby border with the Philistines.

Biblical Equivalent

Is Khirbet Qeiyafa mentioned in the Bible? Some archaeologists have identified this site with a few biblical cities. One is Adithaim (Joshua 15:36). This speculation is based on the cities listed in this verse following a precise geographic order. Based on the geographic location of other cities listed here, Khirbet Qeiyafa would be Adithaim.

Another idea is the city Netaim. This city is referenced poorly by the King James translation: “These were the potters, and those that dwelt among plants and hedges: there they dwelt with the king for his work” (1 Chronicles 4:23; King James Version). The word “plants” is actually the name of a city, Netaim. And the word “hedges” refers to the city Gederah. Based on Khirbet Qeiyafa’s nearby location to the city Gederah spoken of in this same verse (these cities being near to the Valley of Elah), some speculate that Khirbet Qeiyafa could be Netaim.

The more commonly accepted name is the one chosen by the site’s excavator, Yosef Garfinkel: Shaaraim. Shaaraim means “two gates.” Khirbet Qeiyafa has the unique distinction of being the only known First Temple period city equipped with two gates. Typical fortress cities were built with only one gate, since that entry and exit point is the weakest part of the installation. Yet for some reason, Khirbet Qeiyafa has two identical, large, four-chambered gates, one on the south and one on the west. The reason the city had two gates is unclear, but what is clear is that this city certainly matches up with the name “Two Gates”: Shaaraim.

Shaaraim is mentioned in a few Bible verses, all in early contexts (relating to the early inhabitation of Khirbet Qeiyafa). It is mentioned in the list of cities discussed in Joshua 15:36, mentioned above, alongside the city of Adithaim. This shows that Shaaraim was located in the same general geographic area. Another reference to this city is recorded in 1 Samuel 17:52, which describes the aftermath of David’s battle with Goliath (kjv):

And the men of Israel and of Judah arose, and shouted, and pursued the Philistines, until thou come to the valley, and to the gates of Ekron. And the wounded of the Philistines fell down by the way to Shaaraim, even unto Gath, and unto Ekron.

Khirbet Qeiyafa overlooks the Valley of Elah, where this battle between David and Goliath (and the ensuing defeat of the Philistine army) took place. Thus, the timeframe and location fits for identifying Khirbet Qeiyafa as Shaaraim. Another verse provides an interesting possible reference to this city. It comes earlier in the story of David and Goliath: 1 Samuel 17:20 records David arriving with supplies for the Israelites encamped against the Philistines:

And David rose up early in the morning, and left the sheep with a keeper, and took, and went, as Jesse had commanded him; and he came to the barricade, as the host which was going forth to the fight shouted for the battle.

This word for “barricade,” magal, can mean a circular rampart. Khirbet Qeiyafa is a circular fortress atop a mound “rampart.” It is possible that David brought his supplies to this circular fortress where the Israelite army was based, and from which he went down to fight Goliath.

The Bible contains one more reference to Shaaraim, in (1 Chronicles 4:27-28, :31):

And Shimei had sixteen sons and six daughters; but his brethren had not many children …. And they dwelt at … Beth-marcaboth, and Hazar-susim, and at Beth-birei, and at Shaaraim. These were their cities unto the reign of David.

This passage specifically relates the city of Shaaraim to the time of David’s rule. This verse says Shaaraim was populated by Shimei’s family unto, or until, the reign of David. Judging by this verse, and the verses above, we see that if Khirbet Qeiyafa really was the biblical Shaaraim, it was established before David even became king. This verse matches the carbon-14 data and indicates that this fortress city was built during the reign of Israel’s very first king, Saul.

The Discoveries

Khirbet Qeiyafa is a relatively new site to excavators. Its existence has been known to archaeologists and surveyors since the late 1800s, but it was regarded as an Arab village having little to do with Bible archaeology. Only within the last 20 years have archaeologists begun to note in more detail the intriguing structure of the ancient fortress. As such, excavations began in 2007 and have since yielded numerous intriguing finds.

One such item is the large shard of pottery mentioned above, which bears five lines of Hebrew text. This type of artifact is referred to as an ostracon. The weathered, 3,000-year-old ostracon is incomplete and difficult to properly translate, but Émile Puech proposes one possible reading:

Do not oppress, and serve God … despoiled him/her

The judge and the widow wept; he had the power

Over the resident alien and the child, he eliminated them together

The men and chiefs/officers have established a king

He marked 60 [?] servants among the communities/habitations/generation.

This reading is strikingly similar to the biblical record of the nature of King Saul’s appointment (1 Samuel 8:11-19). This potentially would provide support for Khirbet Qeiyafa as a functioning Israelite city at or prior to the establishment of the Kingdom of Israel. Of further note are the individual words used in the inscription—according to Prof. Gershon Galil, eight of the words present in the text appear only in the Bible.

This inscription is problematic for biblical minimalists, because Hebrew writing wasn’t supposed to exist in this region for several hundred more years. Not only does Khirbet Qeiyafa validate the presence of a strong early Israelite kingdom, but it also confirms that writing was known and used for completing business—one of the vital necessities for operating a kingdom in the first place.

Khirbet Qeiyafa also yielded another interesting inscription on a storage jar. This Canaanite inscription bears the words “Ishbaal son of Beda.” Saul himself had a son by this name (1 Chronicles 8:33). This inscription therefore confirms the use of the name for figures belonging to the same period. Moving into later periods in Israel’s history, however, names like this that include the term “Baal” fall out of use.

Further interesting finds included two medium-sized portable “box” shrine-like objects, one of clay and one of stone. Their design features have been compared to similar descriptions in the Bible of the entrance to the temple in Jerusalem. On the stone box, seven ornamental “braces” are depicted above the doorframe. This depiction is actually a comparatively “advanced” design feature found commonly in many later Greek buildings. The fact that the design was already known at such an ancient time indicates that the early Israelite kingdom was in fact far more advanced in construction and design than first thought.

In addition to these other discoveries, archaeologists have also uncovered a large palatial structure at the center of Khirbet Qeiyafa. This is probably where the governor would have sat. The city itself is believed to have housed about 500 to 600 people within its fortified walls, some of the stones of which weighed as much as 8 tons.

Khirbet Qeiyafa Today

It is unknown why Khirbet Qeiyafa was abandoned so early on. Perhaps it was no longer needed as a deterrent against the Philistines after King David finally finished his many battles against them and once Solomon began his long and peaceful reign. Or perhaps King Shishak’s invasion of the Kingdom of Judah in 925 b.c.e. played a part. The general nature and date of the site’s abandonment/destruction requires further investigation.

Khirbet Qeiyafa was somewhat reused on and off after the Kingdom of Judah was conquered by Babylon in the sixth century b.c.e., generally as an agricultural area. There have been a couple of instances of building projects at the site, within a late-Persian/early-Hellenistic time frame and during the Byzantine period. Yet the city-fortress never returned to its state of former glory as under King David.

There is still much archaeological work to be done at this unique site. While a wealth of discoveries have already been found, only an estimated 20 percent of the mound has been excavated thus far. So while debates and arguments abound regarding the veracity of the Kingdom of Israel under Saul and David, the history uncovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa remains a witness—just as it did more than 3,000 years ago as it looked out over the Valley of Elah, where a young man, full of faith and sling in hand, approached a giant.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer