“Go ye now unto My place which was in Shiloh,” God thunders in the book of Jeremiah, “where I caused My name to dwell at the first” (Jeremiah 7:12). Barring Jerusalem, is any city more important to ancient Israel’s history than Shiloh? Shiloh was the capital of Israel and the resting place of the tabernacle for over three centuries. In Genesis 49:10, the word “Shiloh” is used as a name for the Messiah—a name that likely meant “tranquil” or “peaceful” in the original Hebrew. However, Shiloh’s history has been anything but peaceful.

For millenniums, the Hebrew Bible was our only resource for learning about this fascinating city. But over the past century, many archaeological finds have confirmed and enhanced our understanding of biblical Shiloh. Together, archaeology and biblical history reveal the remarkable story of one of the Bible’s most important cities.

Early Canaanite History

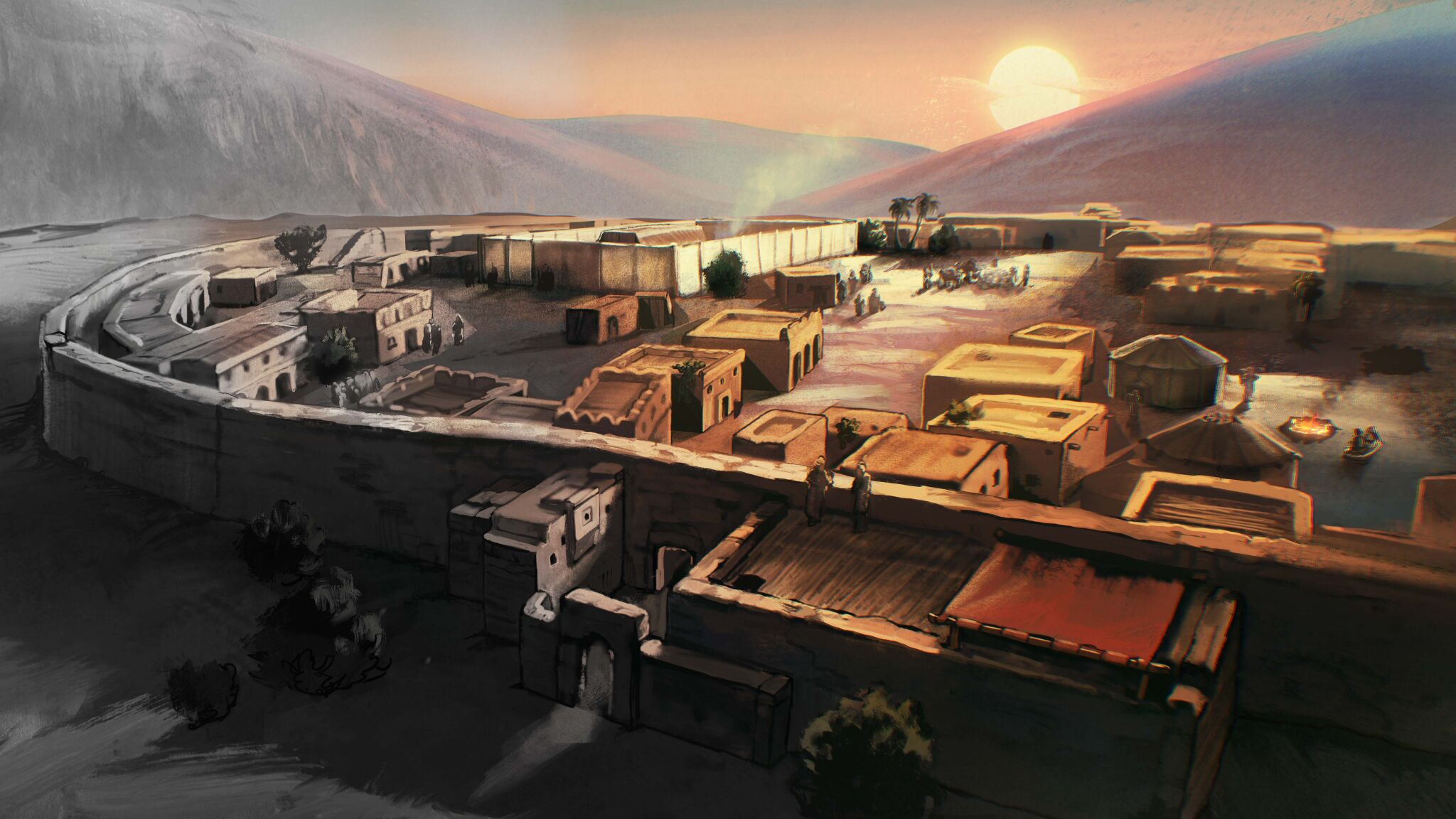

Archaeological evidence suggests that Shiloh was founded sometime in the Middle Bronze Age iib period (circa 1750–1650 b.c.e.). According to Prof. Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist who excavated Shiloh in the early 1980s, Shiloh was likely burned and destroyed during the 16th century b.c.e. Since this was long before the Exodus, the assailants were likely Canaanites. By the time the Israelites arrived in Canaan in the 15th century (according to early Exodus chronology), Shiloh was most likely sparsely populated.

Though the Bible does not record Israel’s settlement of Shiloh, archaeology relates its former Canaanite origins to the words of Moses in Deuteronomy 6: “And it shall be, when the Lord thy God shall bring thee into the land which He swore unto thy fathers, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give thee—great and goodly cities, which thou didst not build, and houses full of all good things, which thou didst not fill …” (verses 10-11).

Israel’s First Capital

According to the book of Joshua, the Israelites within their first years of entering the Promised Land assembled in Shiloh on at least six separate occasions. No other city is listed as a national assembly point. Furthermore, Joshua 18:1 says the “tent of meeting” (the tabernacle) was set up in Shiloh. This points to its use as Israel’s first capital city.

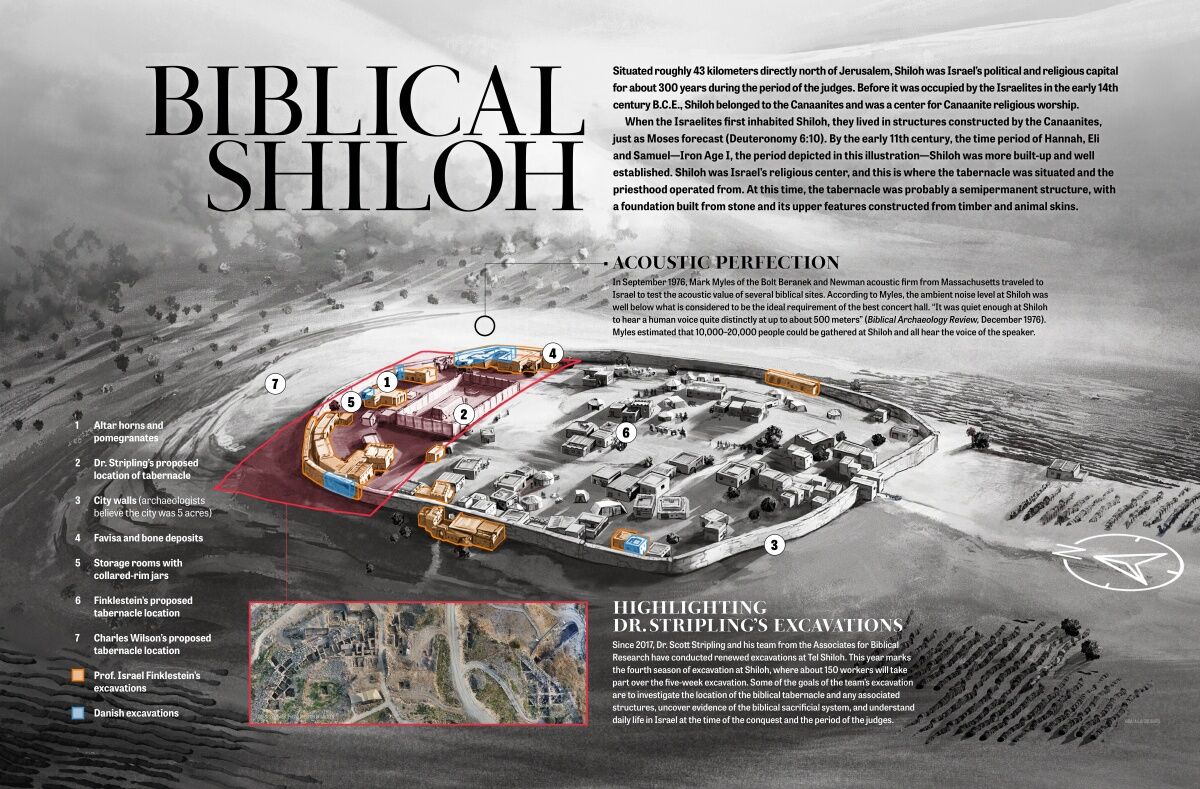

Archaeological evidence from Tel Shiloh indicates that the city was a religious center during the time of Joshua (early part of the Late Bronze Age, 1550–1200 b.c.e.). Archaeologists have found sacrificial animal bone deposits and cultic vessels dating to this time. While a few archaeologists, such as Prof. Finkelstein, interpret these finds as Canaanite, most agree they are evidence of notable religious activity in Shiloh. This indicates the tabernacle once rested there, as the Bible claims.

Besides archaeology, other factors suggest Shiloh was an excellent location for a capital city. It was located near a fertile valley capable of growing enough food for the city’s inhabitants. The city and surrounding farmlands had access to dependable water sources. In addition, the mound (or tel) on which the city was built had steep slopes on three sides, making it easier to defend.

Perhaps most importantly, Shiloh had the right acoustic conditions. Mass communication in the Bronze Age was not easy. There were no microphones or speakers, no Twitter or Facebook. Without digital amplification, Israel’s leaders had to rely on vocal projection and the natural acoustic properties of their surroundings. In the 1970s, sound engineer Mark Myles conducted acoustic tests at Shiloh. According to his results, the ambient noise level of Shiloh was far below the ideal noise requirement of the best concert hall. Myles said it was the quietest spot he had ever measured—quiet enough to hear a human voice clearly at a distance of over 500 meters. Something about the landscape and surroundings at Shiloh makes it possible for sound to travel extraordinarily far.

The Bible records instances of a single speaker (such as Joshua) addressing thousands of people in Shiloh (Joshua 18:8; 22:6). This kind of mass communication would only have been possible in a few acoustically appropriate locations. Shiloh was one of those locations. That mass communication was possible in Shiloh adds credibility to the biblical narrative.

Shiloh in the Period of the Judges

The period of the judges lasted roughly 300 years, from the early-14th to the early-11th centuries b.c.e (Judges 11:26; 1 Kings 6:1). It was the darkest, bloodiest time in Israel’s history. Shiloh is only mentioned four times in the book of Judges, but these few references are enough to prove that a few people still looked to it as the capital of Israel. Judges 18:31 says that the “house of God,” or tabernacle, was still in Shiloh. Israel still used it as an assembly point (Judges 21:12), and an annual feast—perhaps the “Feast of Tabernacles” commanded in Leviticus 23—was kept there (Judges 21:21).

Archaeology corroborates and adds to these details. In his early 1980s excavations, Prof. Finkelstein discovered huge pottery shards and animal bones dating to the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 b.c.e.) in the ruins of Shiloh’s walls. He interpreted these findings as evidence of a tiny Late Bronze Age (judges period) religious center in Shiloh:

“[O]n the summit of the tel, there was probably an isolated cultic place to which offerings were brought by people from various places in the region. The fact that there were very few permanent Late Bronze sites anywhere in the vicinity of Shiloh may indicate that many of these people lived in pastoral groups, in temporary dwellings …. The steadily declining amount of pottery indicates a decrease in activity at the site ….”

At first glance, this seems to undermine the biblical account. Wasn’t Shiloh supposed to be the capital of Israel? Why was it so tiny? Why was it apparently dying out?

Actually, a drastic reduction in activity at Shiloh is exactly what a careful reading of the Bible implies. Notice an important detail recorded at the end of the book of Judges. Following a bloody civil war between Benjamin and the rest of Israel (Judges 19-20), only 600 Benjamites survived. To prevent the extermination of Benjamin, the Israelites needed to find wives for these men. They came up with a cunning plan. At an annual feast, the “daughters of Shiloh” would customarily dance in a meadow near their city. The Israelites suggested that the men of Benjamin lie in wait and simply kidnap the young women while they were dancing. By carrying out this plan, the tribe of Benjamin was saved from extinction.

One key detail from this biblical account provides insight into the state of Shiloh at the time. “Behold,” said the elders of Israel, “there is the feast of the Lord from year to year in Shiloh, which is on the north of Beth-el, on the east side of the highway that goeth up from Beth-el to Shechem, and on the south of Lebonah …” (Judges 21:19). When biblical figures refer to a city, they almost never say anything about its geographical location. Even relatively obscure places are often rattled off as if everyone knew where they were. In this case, however, the elders of Israel felt it necessary to give precise geographical details—about the capital of Israel. Why were they so specific?

What does that say about the size and importance of Shiloh at the time? If Shiloh were a huge, bustling, well-known capital city, describing its location in such detail would have been pointless. The elders of Israel probably had to give directions because the Benjamite men didn’t know where Shiloh was. That implies the city must have been tiny and obscure at the time—just as the archaeological record indicates.

And why were most Israelites apparently ignorant of Shiloh, even though it was the seat of Israel’s government and the religious center? Judges 21:25 answers: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes.” During the period of the judges, Israel didn’t have a strong centralized government, and it also didn’t have a strong centralized religion.

Eli, Samuel and an Iron Age I Resurgence?

The book of 1 Samuel picks up the narrative from Judges. The early chapters of Samuel record the birth and early life of Samuel, Israel’s last judge. According to the biblical chronology, these events occurred in the Iron Age i period (1200–1000 b.c.e.). The biblical account could imply a resurgence of activity in Shiloh at this time.

According to 1 Samuel 1:3, Samuel’s parents journeyed to Shiloh annually to worship and offer sacrifices. At the time, the priests in Shiloh were Eli (the high priest) and his two sons, Hophni and Phinehas, both of whom were corrupt. 1 Samuel 2:13 says that “the custom of the priests with the people” was to steal their meat offerings. “So did they unto all the Israelites that came thither in Shiloh,” verse 14 concludes. The language here seems to suggest there was a sizable number of visitors to Shiloh at this time. Otherwise, how could it have been a custom for Hophni and Phinehas to take advantage of worshipers?

Another indication is found in verse 22, which says Hophni and Phinehas “lay with the women that did service at the door of the tent of meeting.” It is possible that these women were assembling to offer sacrifices. However, the Hebrew word for “did service” could also be translated “assisted” (New Living Bible), meaning that the women were possibly employed to help the priests with their duties at the door of the tabernacle. The fact that the priests needed the help of these women could indicate there must have been sizable numbers of worshipers in Shiloh.

Furthermore, the Bible implies the existence of a permanent structure either surrounding or adjacent to the tabernacle. 1 Samuel 1:9 says Eli “sat upon his seat by the door-post of the temple of the Lord.” 1 Samuel 3:15 describes Samuel opening “the doors of the house of the Lord.” Elsewhere, the Bible usually describes the entrance to a tent as a “tent door” (e.g. Genesis 18:1) or “door of the tent” (e.g. Exodus 29:4). The word “door” without a modifier is almost always used to refer to more permanent structures, such as Lot’s home in Sodom (Genesis 19:6) or Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:33). Additionally, the Hebrew word translated “temple” in the early chapters of 1 Samuel (see 1 Samuel 1:9; 3:3) is hekal. This word is never used to describe the tabernacle or any other tent. Outside of the “temple” in Shiloh, it describes only Solomon’s temple.

In essence, the Bible indicates there was a revival in Shiloh at the end of the period of the judges—both in population and, to some extent, in building.

Archaeology also reveals evidence of a resurgence. “We found remains from Iron Age i virtually everywhere we dug,” wrote Prof. Finkelstein. “From this period we discovered buildings, stone-lined silos and other remains ….” Further, he noted, “The pottery from these buildings is the richest ever discovered at any early Israelite site.” This shows that Shiloh must have had many inhabitants—or at least many visitors—at this time.

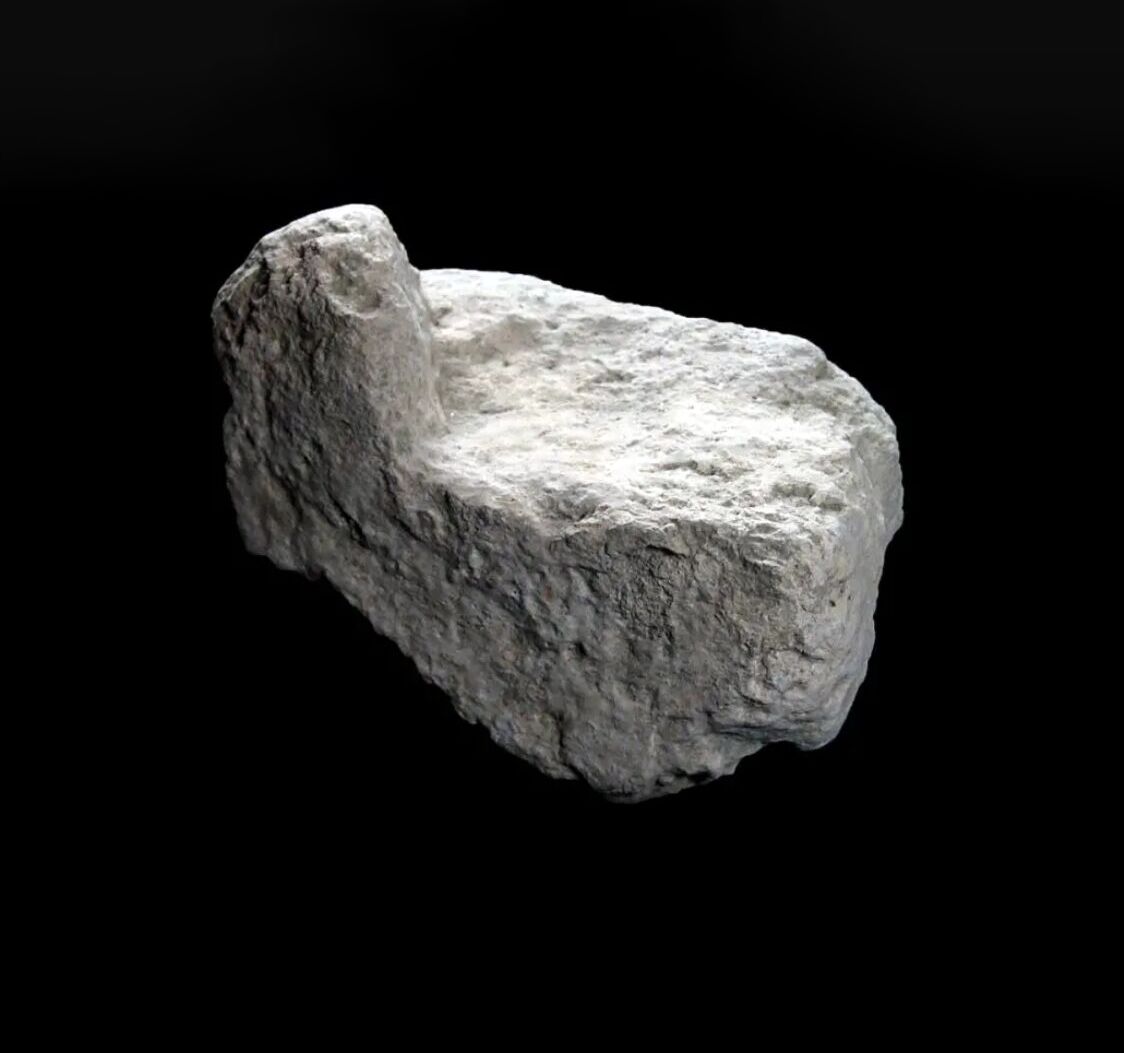

There is also archaeological evidence that the tabernacle was in Shiloh during the Iron Age i period. In more recent excavations, Dr. Scott Stripling unearthed two ceramic pomegranates on the north side of Tel Shiloh. The artifacts date to the Iron Age i period and measure about 8 centimeters in length. The pomegranate was a common motif in ancient Israel’s tabernacle worship. Notably, the high priest’s garments were decorated with pomegranates (Exodus 28:33; 39:25-26).

Dr. Stripling also may have found evidence that tithes were stored in Shiloh. His excavations uncovered numerous large storage rooms around the perimeter of the city. “No other site in Israel has that,” he said in an interview with the Times of Israel. He continued:

“If we’re assuming there was a sacrificial system there … well, what do you bring if you’re going to bring your tithe? You can’t make a secure online donation at Tabernacle.org; you can’t write a check. What are you going to do? You’re going to bring commodities: barley, figs, pomegranates. And so what do we find? Storage rooms around the entire perimeter [of the tel].”

This fits well with other evidence from Prof. Finkelstein’s work in Shiloh. Finkelstein discovered several large, collared-rim storage jars in the city, which also could have been used to store tithes.

Three stone altar horns unearthed in Stripling’s excavations also indicate the presence of the tabernacle in Iron Age i Shiloh. Israelite altars had “horns” attached to each of their four corners (Exodus 27:2). The horns were used in various rituals and also provided refuge for fugitives who clung to them.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that the tabernacle was once in Shiloh is the large quantity of animal bones discovered there. Prof. Finkelstein’s excavations unearthed huge animal bone deposits dating to the Iron Age i period. The overwhelming majority of these bones were from animals that would have been used in the Israelite sacrificial system. Less than 1 percent were pig bones.

Additionally, Finkelstein found that about 60 percent of the bones were from the right side of the animal, while only 40 percent were from the left side. Dr. Stripling believes that this seemingly bizarre phenomenon can be explained by Leviticus 7, which says that the priest’s portion was to come from the right side of the animal. Since Shiloh was probably predominantly inhabited by priests and Levites, it makes sense that archaeologists would uncover a disproportionately large number of bones from the priests’ portions of sacrificed animals.

In short, the archaeology of Iron Age i Shiloh fits precisely with the Bible’s account. There is solid evidence supporting the resurgence of Shiloh implied in the early chapters of 1 Samuel. There is also solid evidence that Israel’s priestly worship was centered in Shiloh at the end of the period of the judges. If this is true, the tabernacle was undoubtedly in Shiloh too—but where?

Finding the Tabernacle?

Archaeologists have debated the tabernacle’s ancient resting place for years. Scholars have seriously considered at least three locations. Some, such as Prof. Finkelstein, believe the tabernacle must have been located near the building complex in the city proper. They conclude it probably rested at the summit of the tel. Others, most notably Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, think it could have been located on the grassy plain south of the tel. Byzantine Christians built several structures on the area, which could indicate there was an oral tradition that the tabernacle once stood there.

Another compelling hypothesis was posited by Maj. Charles Wilson in 1866. While surveying Shiloh for the Palestine Exploration Fund, Wilson noticed a stretch of flat bedrock about 146 meters north of the tel. Upon further investigation, it appeared to have been intentionally flattened and squared. Furthermore, the dimensions of the flattened area closely paralleled the dimensions of the tabernacle described in Exodus 26 and 27. The platform was also aligned east to west, fitting with God’s command to make “the hinder part of the tabernacle westward” (Exodus 26:22). Additionally, the northern platform would have been geographically favorable for defense.

Because Tel Shiloh is steeply sloped on its northern, eastern and western sides, the city is most easily approached from the south. For this reason, most archaeologists believe Shiloh’s entrance was on the southern side of the city. This crucial fact is at the premise of another key argument in favor of Wilson’s hypothesis.

According to the biblical account, Israel lost the ark of the covenant to the Philistines in the battle of Ebenezer (1 Samuel 4). After the defeat, a messenger ran back to Shiloh with the dreadful news: “And when he came, lo, Eli sat upon his seat by the wayside watching; for his heart trembled for the ark of God. And when the man came into the city, and told it, all the city cried out. And when Eli heard the noise of the crying, he said: ‘What meaneth the noise of this tumult?’ And the man made haste, and came and told Eli” (verses 13-14).

From other passages, we know that Eli’s chair was located near “the temple of the Lord” (1 Samuel 1:9-13). If the messenger had to pass through the city to reach Eli, then the tabernacle must have been on the opposite side of Shiloh from its southern entrance—on the north side.

Considering all this evidence, Wilson’s hypothesis seems logical. However, it has been met with some criticism in the century and a half since its origination. Notably, when archaeologist Ze’ev Yeivin excavated the northern platform from 1981 to 1982, he found no remains from the Iron Age i period. This led archaeologists like Dr. Finkelstein to dismiss the northern platform theory. However, more recent excavations have uncovered what are likely Iron i remains from this area.

In recent years, and as a result of his extensive excavations, Dr. Stripling has formed an entirely new conclusion about the location of the tabernacle. Stripling believes the tabernacle will be found in the northern area of the tel, which would match the biblical narrative. However, unlike Wilson’s idea, Stripling’s location is inside the fortified city, which makes logical sense for such a sacred shrine. So far, Stripling has identified several walls from the Iron i period that match the biblical dimensions of the tabernacle. One of the walls was previously exposed in Professor Finkelstein’s excavation, who dated it to the Middle Bronze period. Stripling has dated this same wall to the late judges period. Finally, the broken altar horns, pomegranate and bone deposits were all discovered in areas adjacent to the platform area, adding to the evidence that the tabernacle was close by. Dr. Stripling hopes that this season’s excavation will uncover the final remaining corner of the rectangular building (see interview with Dr. Stripling on page 20 for more details).

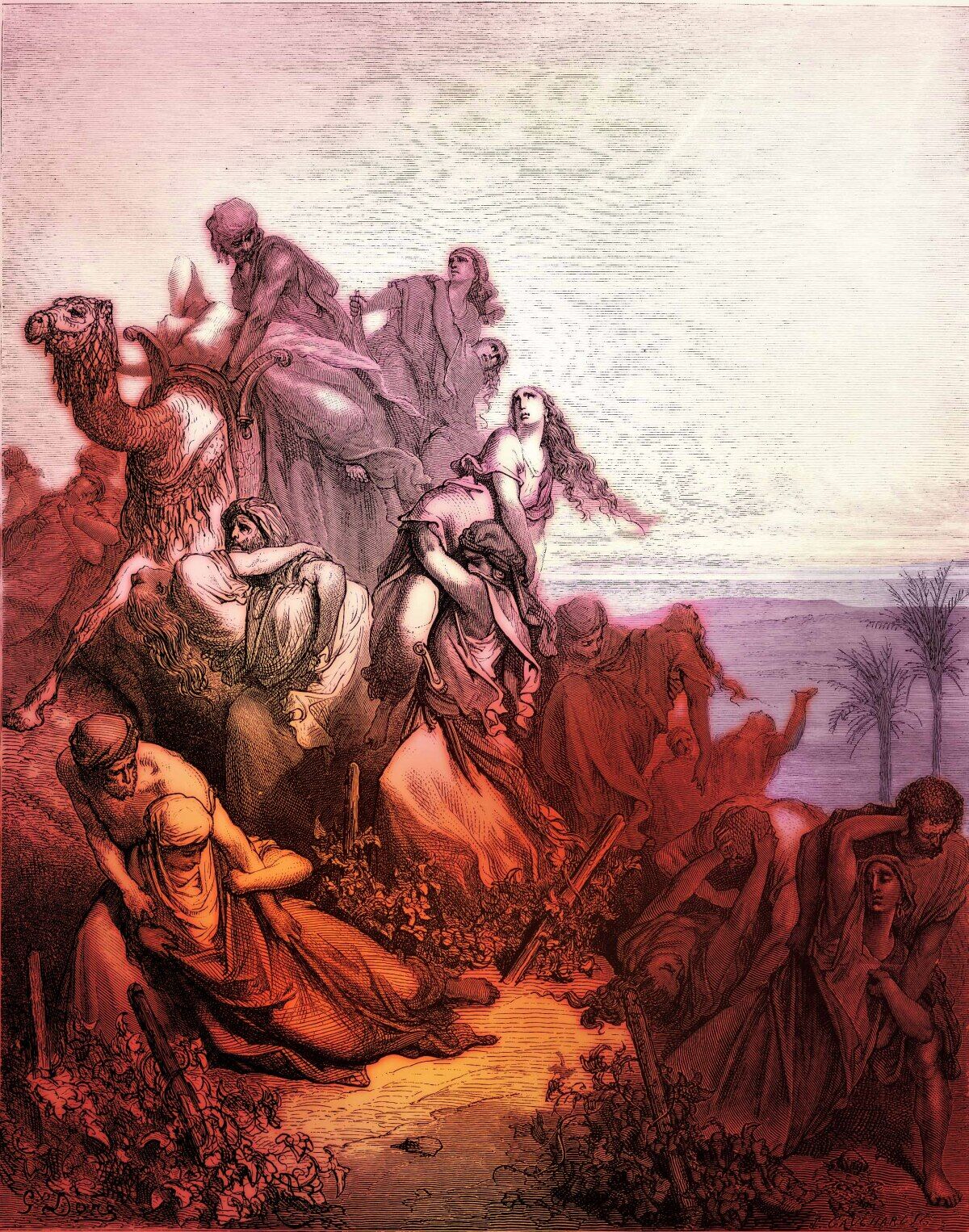

The Fall of Shiloh

The Bible records a tragic close to Shiloh’s illustrious history. At the end of the priesthood of Eli, the Israelites foolishly removed the ark from Shiloh and took it to the battle of Ebenezer, believing it would help them defeat the Philistines. The results were disastrous: “And the Philistines fought, and Israel was smitten, and they fled every man to his tent; and there was a very great slaughter; for there fell of Israel thirty thousand footmen. And the ark of God was taken …” (1 Samuel 4:10-11).

When the high priest Eli heard the awful news, he was so shocked that he fell backward off his chair and snapped his neck. After this harrowing account in 1 Samuel 4, the Bible does not mention Shiloh (apart from a few retroactive references) until 1 Kings 14:2—over a century later in the chronology of biblical events. What happened to Shiloh?

The Bible implies it was destroyed. After the Philistines took the ark, they were cursed with awful plagues for seven months (1 Samuel 6:1). When Philistine leaders decided to return the ark to Israel, the Israelites took it to Kirjathjearim, where it remained (1 Samuel 7:1-2). Why didn’t they take it back to Shiloh? Probably because the Philistines had destroyed it after the battle of Ebenezer.

Other biblical writings confirm this. Psalm 78:60 says God “forsook the tabernacle of Shiloh, The tent which He had made to dwell among men.” In the seventh century b.c.e., God, through the Prophet Jeremiah, used Shiloh to illustrate what would happen to Judah if it failed to repent: “[G]o ye now unto My place which was in Shiloh, where I caused My name to dwell at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of My people Israel” (Jeremiah 7:12). God promised to destroy Jerusalem just like the Philistines destroyed Shiloh: “[T]hen will I make this house like Shiloh, and will make this city a curse to all the nations of the earth. … This house shall be like Shiloh, and this city shall be desolate, without an inhabitant …” (Jeremiah 26:6, 9).

Once again, archaeological evidence fits precisely with the Bible. In the 1930s, Dr. Hans Kjaer and his Danish team found a destruction layer in Shiloh dating to the middle of the 11th century. Though originally controversial, dating of the ceramics in Kjaer’s burn layer was later confirmed by Dr. Yigal Shiloh. More recently, Dr. Stripling carbon-dated remains from the burn layer to 1060 b.c.e., plus or minus 30 years. According to Stripling, the destruction of Shiloh probably happened around 1075 b.c.e.

‘Ahijah the Shilonite’—Resettlement in the Iron Age II Period

The Bible does not say exactly when Shiloh was resettled after its destruction. However, according to 1 Kings, resettlement occurred at least as early as the reign of King Solomon.

Toward the end of Solomon’s reign (circa 931 b.c.e.), God sent a prophet named Ahijah to prophesy of the split between Israel and Judah. 1 Kings 11:29 calls him “Ahijah the Shilonite,” and a later verse confirms that he lived in Shiloh (1 Kings 14:2). There must have been at least a small settlement in Shiloh during the 10th century (Iron Age ii period).

Furthermore, the Bible implies Shiloh was still inhabited after the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 b.c.e. After Jeremiah returned to Jerusalem, “there came certain men from Shechem, from Shiloh, and from Samaria, even fourscore men … with meal-offerings and frankincense in their hand to bring them to the house of the Lord” (Jeremiah 41:5).

Archaeologists have found evidence of Iron ii habitation in Shiloh. “Following a period of abandonment, a small village, the poor remains of which were found in several places, occupied the site in Iron Age ii,” wrote Prof. Finkelstein. “As the Bible reflects, and our excavations confirm, Shiloh never really recovered from the Philistine destruction in about 1050 b.c.”

The Legacy of Shiloh

Besides Jerusalem, is any city more central to the history of ancient Israel than Shiloh? It was Israel’s first capital city and remained so for almost four centuries. It was a gathering place for important Israelite leaders. It was the resting place of the tabernacle and the religious center of Israel. However, after its destruction, Shiloh became a warning. “[G]o ye now unto My place which was in Shiloh,” God warns, “where I caused My name to dwell at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of My people Israel” (Jeremiah 7:12). When Jeremiah wrote that, Shiloh was in ruins, vividly illustrating the calamity that would shortly befall Jerusalem. Today, over 2,500 years later, Shiloh is still in ruins. Though many archaeological excavations have occurred there, the Tel Shiloh we know today likely bears an uncanny resemblance to the ancient ruins of the city in Jeremiah’s day.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer