Mizpah, in Benjamin’s territory, was a prominent city in the biblical account. Identifying the original location of it, however, has been problematic.

Tell en-Nasbeh is one of the most likely locations. The ancient city lies about 12 kilometers north of Jerusalem. It is situated on the important Central Ridge Road, or “the spine,” between the southern cities of Hebron and Jerusalem and the northern cities of Samaria and Shechem. Mizpah, meaning “watchtower” or “lookout,” was called such because it was from that location that travelers from the north would first see Jerusalem.

Dr. William Frederic Bade of the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, California, excavated about two thirds of Tell en-Nasbeh in five seasons of digging (from 1926 to 1935). When Dr. Bade died in 1936, his chief assistant, Chester C. McCown, completed the two-volume final report of the excavations.

After five seasons of excavation, does the evidence indicate Tell en-Nasbeh is the biblical Mizpah?

Discovery

In 1926, Dr. Bade first arrived in Israel to begin excavations. Dr. W. F. Albright suggested Tell en-Nasbeh, saying it was an important mound because of the uncertainty surrounding its identification. Some believed this mound to be the Mizpah where Samuel built a “school of the prophets” and where Governor Gedaliah established his headquarters after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem. Others believed the ancient city of Mizpah to be at the site of Nebi Samwil (meaning “the Prophet Samuel”), another tell five miles southwest of Tell en-Nasbeh. According to tradition, this is the site where Samuel was buried (though the Bible states that he was buried in Ramah; according to Christian tradition, the Crusaders re-interred his bones here, after discovering them at Ramle).

The mystery and intrigue surrounding Tell en-Nasbeh, and some promising surface discoveries, were enough to sufficiently peak Dr. Bade’s interest to at least conduct an exploratory excavation.

The first day of digging began on April 3, 1926. The four Egyptian workers began cutting a section, and within the first four hours of digging, they had found the beginnings of a wall. Two days later, they had exposed a large part of the great city wall under only a meter and a half of dirt. So far, the excavation seemed promising.

The excavation uncovered an abundance of pottery and a number of buildings including tombs, grain pits and cisterns, which had been carved into the limestone rock of the hill. However, the chief discovery was the city’s defenses.

City Defenses

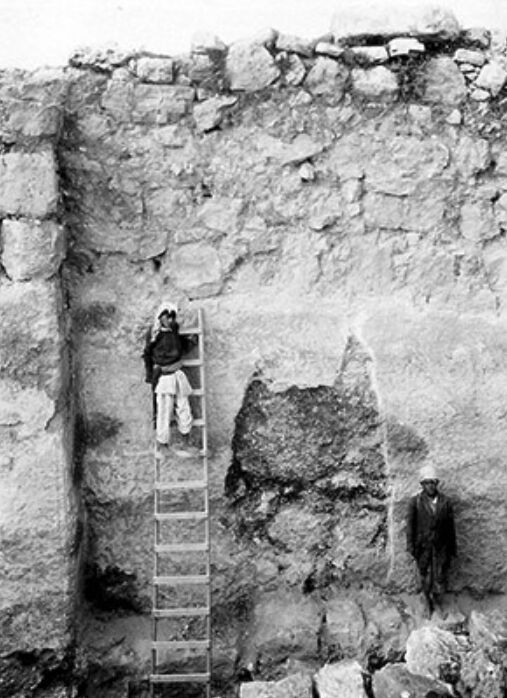

The ancient city had two sets of walls: a smaller inner wall and a large outer wall. The great outer wall turned the hilltop into “one of the strongest Hebrew fortresses” in the region. The wall was “far heavier and more imposing than any other which had up to that time been found in Palestine,” wrote McCown. The wall measured about 660 meters in circuit, and was an average of 4-plus meters thick. The tallest preserved section of the wall was 5.5 meters above bedrock, though the original wall would have been built much higher; it is estimated the wall may have been 12 to 14 meters tall. Eleven towers projected from the wall.

Regarding the construction of the southern portion of the wall, Dr. Bade wrote:

The bottom foundation of the wall consisted of a platform of immense rocks, a yard or more in thickness and projecting a foot or two beyond its face. The vertical crevices between them had been left unfilled as if to provide drainage. The wall throughout was built of limestone rocks laid in clay mortar.

Some of the largest stones were so heavy, three or four workmen couldn’t budge them. The wall was overlaid with a thick coating of plaster to make the walls difficult to climb, a common military strategy of the day.

According to McCown and Bade’s report, the great wall of Tell en-Nasbeh dates to the late 10th century b.c.e. This is significant because of the biblical account of Mizpah during this time.

At the end of the 10th century b.c.e., when the northern 10 tribes of Israel broke away, Mizpah became a border outpost of the kingdom of Judah. During the reign of King Asa (circa 900 b.c.e.), Judah was locked in a war with its Israelite neighbors. Israel’s King Baasha had fortified the border city of Ramah. Asa, however, used temple treasure to buy the assistance of the Syrian King Ben-hadad, who came and attacked Israel. Asa then demolished Ramah, using its stones to heavily fortify his border city, Mizpah. “Then king Asa … carried away the stones of Ramah, and the timber thereof, … and king Asa built therewith Geba of Benjamin, and Mizpah” (1 Kings 15:22). Such a crucial defensive outpost on Judah’s border with Israel would explain the need for extremely high, thick walls.

McCown wrote, “The conclusion was reached without dissent on the part of anyone, so far as I know, that the great wall in its entirety was built in the Iron Age and apparently near the close of the Early Iron Age.” The city’s gate complex was a fairly simple two-chamber gatehouse. As with the great wall, it is dated to around 900 b.c.e. The inner city wall, though, was much older.

The best dating given for the inner wall is the 12th century b.c.e. (Iron i). The continuous occupation that occurred within this wall corresponds with the biblical importance of Mizpah during the period of the judges, and later during the life of the Prophet Samuel and his establishment of a prophets’ school and administration center in Mizpah (e.g. 1 Samuel 8:15-16). The presence of such an establishment would have caused much growth and development in the city, pointing to the abundance of Iron i remains.

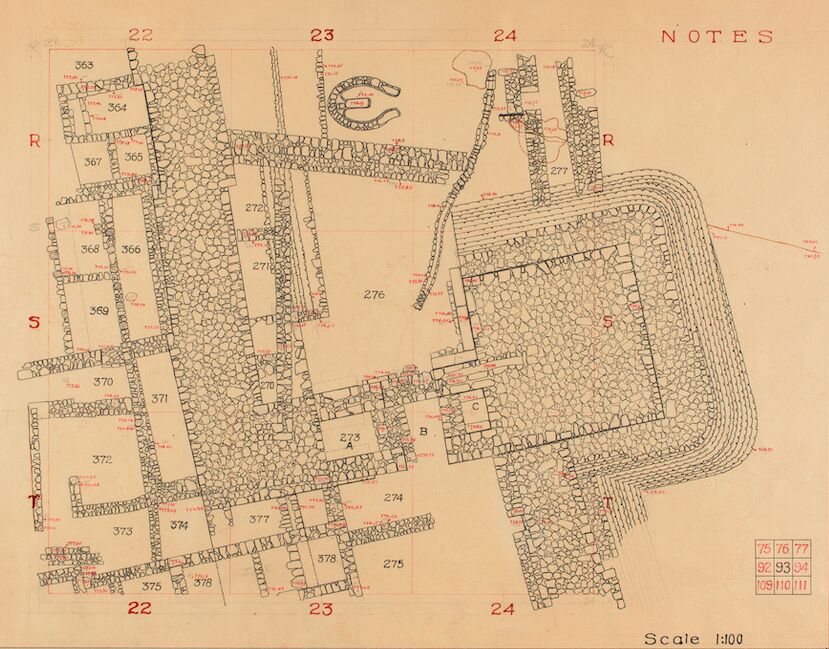

The inner wall runs around the northern and southern ends of the tell; however, the trail seems to be lost to the eastern and western sides. Many houses and storage buildings were built against the inner wall in the typical Israelite fashion, both strengthening the wall and saving extra building materials for the houses.

Occupation

During these later kingdom years, there appears to have been “an almost continuous ring of occupation around the whole of the tell.” According to Dr. Bade, since small finds were scattered throughout the tell, it appears that the tell must have been completely covered with houses. The western slope of the hill was more densely populated than the eastern slope, probably due to the cool winds that came from the Mediterranean Sea.

Mizpah, of course, became the administrative capital for Judah after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem. An important observation from the Tell en-Nasbeh excavations is the absence of a massive burn layer between the 605 to 585 b.c.e. Babylonian invasions, such as was found in Lachish and Jerusalem. Instead of being destroyed, the city became the new capital of Judah. The lack of a burn layer adds further credibility to the claim that Tell en-Nasbeh is the site of biblical Mizpah.

Prof. Jeffrey R. Zorn wrote that at the outset of the Babylonian period, the Iron ii city witnessed a “dramatic change in Mizpah’s function, from border fortress of a small hill country kingdom to the center of a minor district in a large empire.” After Gedaliah was appointed governor of Judea by Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 25:22), he established his administrative center in Mizpah (verse 23). This became an important governing district within the larger Babylonian Empire.

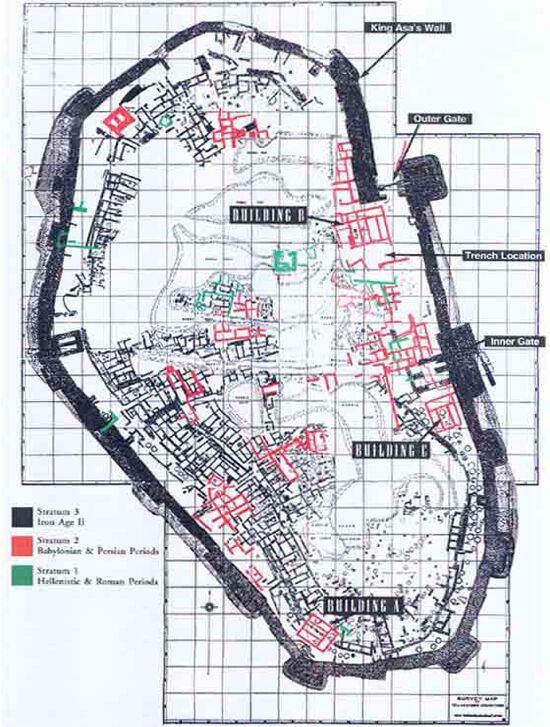

Dating to the period of this establishment of Mizpah as the new “capital” of Judah, Dr. Bade’s excavation discovered a sudden series of construction projects on the tell. (The majority of the structures outlined in red, in the picture at left, are dated to this Babylonian period expansion. They also continue into the Persian period. Black outlines represent Iron ii construction.)

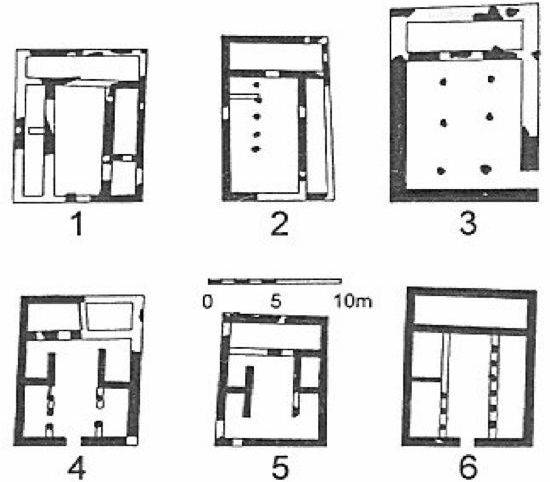

The old ring-road settlement was filled in, and small houses along narrow roads were replaced by at least a dozen larger four-room dwellings about twice the size of their predecessors. Unlike the older architecture, the classic Judean four-room houses of the Babylonian period “were more carefully constructed.”

Tell en-Nasbeh also produced artifacts related to the local government following the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem. Thirty-two “mzh” (or “m(w)sh”) stamp impressions (probably identifying goods delivered from the town Mozah to the provincial capital) were uncovered at Tell en-Nasbeh, with only 10 others identified from other sites—sites only associated with the tribal land of Benjamin. None were found from the primary “Mizpah competitor” site, Nebi Samwil. This indicates that Tell en-Nasbeh was the most important center of administration during the Babylonian period—as was the biblical city of Mizpah.

Jaazaniah Seal

While excavating a tomb at the western necropolis of Tell en-Nasbeh in 1932, Dr. Bade uncovered a beautifully finished black-and-white onyx seal bearing the inscription “Belonging to Jaazaniah, servant of the king.”

The inscribed seal dates to roughly a year before King Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest of Jerusalem in 586 b.c.e. when he carried away Zedekiah captive and appointed Gedaliah governor. This seal likely belonged to the biblical Jaazaniah, who was among a number of officers who came to Mizpah to swear his allegiance to Gedaliah (2 Kings 25:23). It is possible that this man was among those assassinated at Mizpah, together with the governor, by the usurper Ishmael (Jeremiah 41). This seal of Jaazaniah was found in a reused Iron Age tomb, indicating the seal may have been buried with him after his death.

The onyx seal is divided into three sections. The top register of the seal says, “Belonging to Jaazaniah,” and the middle register says, “servant of the king.” The phrase eved hamelech, “servant of the king,” is a biblical phrase used in 2 Kings 25:8 along with the phrase “captain of the guard,” titles that could have been used interchangeably—thus fitting with Jaazaniah’s distinction as some kind of “captain” in verse 23.

The bottom third register has a picture of a fighting rooster. Dr. Bade wrote in his book A Manual of Excavation in the Near East, “In any event, the fighting cock was an appropriate symbol on the seal of a soldier”—additional support that the Jaazaniah seal matches with the biblical commander.

And the winner is …

1 Maccabees 3:46 says, “Wherefore the Israelites assembled themselves together, and came to Mizpah, over against Jerusalem; for in Mizpah was the place where they prayed aforetime in Israel.” Some use this scripture to say Nebi Samwil, not Tell en-Nasbeh, is Mizpah. Because Mizpah is described as “over against” or “opposite” to Jerusalem—because it is closer—Nebi Samwil must be Mizpah. However, the distance is negligable—Tell en-Nasbeh is only four kilometers farther from Jerusalem. Another key argument is based on the route Ishmael took from Mizpah (Jeremiah 41), escaping with his captives toward the land of Ammon via the region of Gibeon. Skeptics say that Nebi Samwil as Mizpah better fits with the route Ishmael took. Again, though, distances are negligible, and the geography relating to this journey is still very much up for debate.

Crucially, though, Nebi Samwil has not revealed any Iron i remains nor any remains from the Babylonian period—two vital points of Mizpah’s occupation, according to the biblical account.

When examining the evidence from the two sites, the sheer amount of archaeological discoveries from Tell en-Nasbeh that correspond with the biblical account strongly suggests that Tell en-Nasbeh is Mizpah.

Tell en-Nasbeh has produced the Iron i remains fitting with the establishment of Samuel’s college; massive Iron ii defenses fitting with King Asa’s border outpost project; and significant Babylonian-period stratum matching the transfer of Judah’s administrative capital to Mizpah, after the destruction of Jerusalem. The rare artifacts like the mzh stamp impressions and the Jaazaniah seal add more circumstantial evidence pointing to Tell en-Nasbeh.

Zorn wrote: “There is no doubt that important late material comes from Nebi Samwil, but in this world of subjective analysis the bulk of the evidence still favors Tell en-Nasbeh as the most likely candidate for Mizpah.” That it is—but of course, the reader can make up his own mind.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer