Today, the area including the Golan Heights serves as a strong outpost for Israel’s northernmost border. The city that served this same purpose anciently was the biblical city of Dan (known today as Tel Dan; “Tel” referring to the archaeological-mound style of the site). The remains, beautifully preserved to this day, show the strength of ancient Israel’s northernmost city. It is located in one of Israel’s most beautiful areas with lush, green countryside and forests fed by runoff from surrounding mountains. Unfortunately, Tel Dan also served as one of ancient Israel’s chief centers of pagan worship.

Archaeological excavations continue at Tel Dan this year, providing us more information about this incredible biblical location.

Before the Israelites

The city’s name before it was conquered by the tribe of Dan was Laish (Judges 18). Like many locations in Israel, it had a long-established history before the arrival of the Israelites. The patriarch Abraham was well familiar with this area—he pursued the invading kings who had captured his nephew Lot to this location of northern Dan (Genesis 14:14).

Before Israel’s arrival to the Promised Land, Laish was inhabited by Canaanites. Judges 18:27-28 (kjv) show us that the people who lived there were at peace and secure, isolated from other cities. It was an ideal location. Archaeologists have found a massive city gate complex made entirely out of mud brick, constructed sometime between 1800-1700 b.c.e. (several hundred years before the Exodus). This incredible gate, preserved to 47 courses high, displays one of the earliest archways ever found.

The Danite Invasion

The tribe of Dan initially inhabited one location in the Promised Land. It was situated along the coast, bordering the territory of the Philistines. However, part of the tribe broke away in search of more territory in which to expand (Joshua 19:47). The group traversed far north to the area of Laish (called Leshem in the book of Joshua). Judges 18 tells the story of these breakaway Danites adopting pagan idolatry from the “house of Micah” before traversing further north than any other tribe and conquering the territory of Laish.

“And they took the things which Micah had made, and the priest which he had, and came unto Laish, unto a people that were at quiet and secure: and they smote them with the edge of the sword, and burnt the city with fire. And there was no deliverer, because it was far from Zidon, and they had no business with any man; and it was in the valley that lieth by Bethrehob. And they built a city, and dwelt therein. And they called the name of the city Dan, after the name of Dan their father …” (Judges 18:27-29; kjv).

The new city of Dan was eventually built up, particularly during the later time of the Israelite monarchy. It became a major Israelite outpost, complete with large city walls.

Jeroboam’s Sin

Hundreds of years after the city of Dan was established, Jeroboam led the northern 10 tribes of Israel to break away from King Rehoboam and his oppressive rule from Jerusalem. From that point forward the tribes of Israel were split into two kingdoms: the kingdom of Judah in the south and the kingdom of Israel in the north. However, new King Jeroboam was worried: Jerusalem, in the Kingdom of Judah, remained the only rightful place to worship the true God. Jeroboam feared that if his people continued to travel to Jerusalem to worship, they would eventually kill him and return back to Rehoboam.

“Whereupon the king took counsel, and made two calves of gold, and said unto them, It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt. And he set the one in Bethel, and the other put he in Dan. And this thing became a sin, for the people went to worship before the one, even unto Dan” (1 Kings 12:28-30; kjv).

Thus Jeroboam instituted pagan calf worship as the “national” religion of the northern Kingdom of Israel, setting up the two centers of idolatry in Bethel and Dan.

The archaeological record directly corroborates this history. Within the large walls of Tel Dan, dating to this period, a massive open area was found dedicated to pagan worship. A platform and remains from a huge altar were discovered. This altar would have stood around three meters tall (a steel frame reconstruction sits at the site today, giving visitors an idea of the size of this altar). Two flights of stairs led up to the altar surface. A large, elevated podium area accompanied the altar (perhaps the place for the golden calf), along with sacrificial instruments and a smaller altar that was also found. This was clearly a busy place of pagan worship, meant to accommodate large numbers of devotees who had followed Jeroboam’s orders not to worship in Jerusalem.

This cultic site was used throughout the northern kingdom’s existence—even surviving King Jehu’s purges (2 Kings 10:29). In fact, so popular was this place of worship that it continued to be used into the Hellenistic period, with a dedication inscription to “the god that is in Dan” dating to the reign of Antiochus iii (223–187 b.c.e.—the father of the famous Antiochus Epiphanes). The site was phased out in favor of nearby Banias during Roman times. With the worship at Tel Dan abandoned, Amos 8:14 comes to mind:

They that swear by the sin of Samaria, And say: ‘As thy God, O Dan, liveth’; And: ‘As the way of Beer-sheba liveth’; Even they shall fall, and never rise up again.

House of David

Being the northernmost border city for the Israelite kingdom (2 Samuel 3:10; 2 Chronicles 30:5; etc.), the city of Dan remained vulnerable to attacks from northern belligerents wanting to invade Israel. As such, the city changed hands a number of times as Israel was invaded by conquering nations. The Syrians, or Arameans, were a particular foe.

The Bible records a great strife between King Asa of Judah and King Baasha of Israel. King Asa in fact went so far as to strip the temple of its treasures and deliver them to Ben-hadad of Syria, requesting him to invade the northern Kingdom of Israel. “And Ben-hadad hearkened unto king Asa, and sent the captains of his armies against the cities of Israel, and smote Ijon, and Dan …” (1 Kings 15:20). This was just one of a number of incursions by the Syrians suffered by the city of Dan.

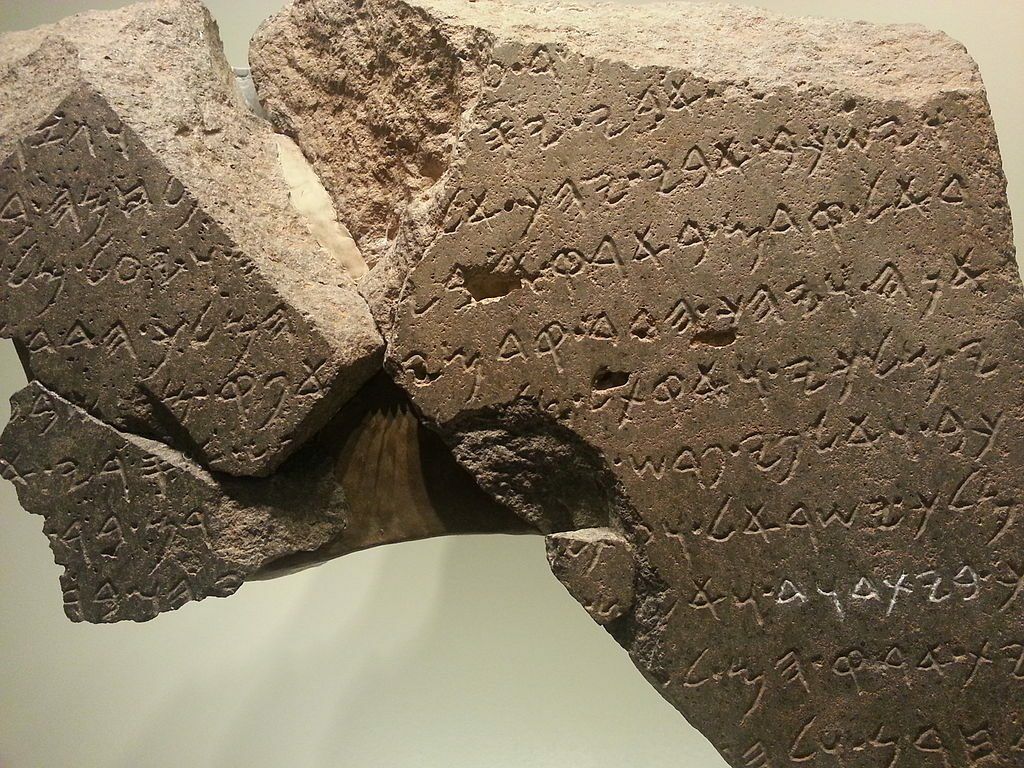

Evidence of one of these invasions lay in a special broken stone used as part of a gate construction in the city of Dan. King Hazael of Syria, who was the third king after the above-mentioned Ben-hadad, had conquered much Israelite territory during his reign in the ninth century b.c.e., and he boasted of his gains on a dark gray “victory stone” inscribed in Aramaic. Some time after the city of Dan was repossessed by the Israelites, this victory stone was broken and used as part of the gate construction.

During excavations in 1993, a large chunk of this stone was found. Part of it read:

And I killed two [power]ful kin[gs], who harnessed two thou[sand cha]riots and two thousand horsemen. [I killed Jo]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel, and I killed [Achaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g of the House of David. And I set …

This find rocked the archaeological world. There had been, to that point, no archaeological evidence of King David. Many archaeologists simply considered him to be a purely mythological figure, or at best an insignificant hilltop chieftain. Here, found in the gate of Israel’s northernmost city, was found proof of David’s existence. While the inscription was made over 100 years after David’s death, it shows that his influence as king was broadly known and that the southern Kingdom of Judah was still being referred to by the name “House of David”—a title king Jeroboam himself had recognized when he led the breakaway of the northern kingdom (1 Kings 12:16).

This victory stone is today known as the Tel Dan Stele. Not only is its reference of King David of special interest, but also its reference to “Israel”—only three other known ancient artifacts also reference that term.

The Final Collapse

The final fall of Dan as an Israelite city occurred during the late eighth century b.c.e., as the northern kingdom of Israel began to be conquered and its inhabitants taken into slavery. Destruction layers found during excavations prove the city’s collapse at that time—it was perhaps one of the first Israelite cities to fall to the powerful Assyrian Empire. This marked the end of the city’s use as a powerful Israelite fortress.

It didn’t, however, completely mark the end of the city as an Israeli reference point and settlement area. In 1939, a Jewish kibbutz was established at Dan, and the area was formally included in Israel’s territory upon the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. Since then, Tel Dan and its surrounding community have continued to suffer the problems associated with being a border town. During the 1948 War of Independence, women and children were evacuated from the kibbutz while the area managed to successfully hold out against the Syrians positioned in the strategically advantaged Golan Heights. Throughout the decades after the war, the community in Dan remained vulnerable to nearby Syria. During the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel managed to repel the attacking Syrians and capture the entire Golan Heights, which has since given the northern country as a whole (and the community in Dan in particular) a much more secure environment.

Tel Dan today is a beautiful, lush nature reserve. Its incredible history and remains, available for any visitor to see, are a strong reminder of the depth of paganism to which northern Israel had fallen, and the resulting repeated conquering of the city. The site is also a powerful validation of the Bible’s historical account, including its greatest king—David.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer