Both the Hebrew and Arabic names for the city Hebron mean “friend” or “comrade.” It was named this because, according to both Jewish and Muslim traditions, Hebron contained the tomb of Abraham, the “friend of God.” Hebron is the second-most holy site to Jews, and to Muslims it is the second-most important site within Israeli borders. Far from a city of friendship though, Hebron has become one of the most volatile areas of Israel (particularly over the last century). Despite the tense and often deadly political and cultural climate, this biblical city is archaeologically one of the most interesting patriarchal-period sites in Israel.

Early History

The ancient biblical center of Hebron has been identified as the archaeological site Tel Rumeida. The earliest period of settlement spans the third millennium b.c.e. (approximately 3200–2200 b.c.e.). During this time, Hebron was a fortified settlement covering about 7.5 acres. The city was afterward abandoned, for an unknown reason (interestingly, this is right around the biblical time frame of Noah’s Flood), and later rebuilt during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550 b.c.e.). During that time, the city was occupied by a Canaanite-Hittite population, which established Hebron as an important city with larger fortifications and defenses. A large hewn-stone wall with an external glacis surrounded the Canaanite city limits, providing crucial defense for the population.

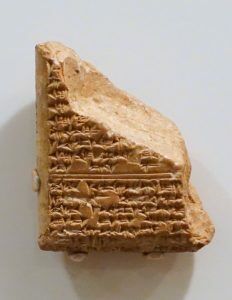

Dating to this early Canaanite time period, a cuneiform inscription was discovered listing quantities of sheep bought and sold to Semitic peoples in the land. One of them could have been the famous sheepmaster and patriarch Abraham, or perhaps one of his children or grandchildren. It was during this early period that he and his family were on the scene. Sheep trade wasn’t particularly common at that time in Canaan—the preferred livestock were goats, which were much more hardy and a better fit for the environment. (It is interesting that whenever you find Israelites, you seem to find sheep.)

A Patriarch, a Gate, and a Cave

The Bible describes Abraham spending a great deal of time in Hebron. It was to this area that he came, after he and his nephew Lot parted ways following the over-expansion of the herds and families of each. And it was from this area that Abraham made the first transaction of land within Canaan for his family and descendants (long before the Israelites entered after the Exodus): a plot of caves within which to bury his wife Sarah (and which would serve as a future burial ground for following generations). The Bible tells us that this transaction of land took place at the city gatehouse.

During the late 1990s, a large gate-tower was discovered at the southeastern corner of the tel, dating to the Middle Bronze period. Based on the discovery and the dating, this could very well be the same gate complex mentioned in Genesis 23:10 from which Abraham bought his burial ground. City gatehouses were quite a common place for official transactions and for passing judgments. Genesis 23:3-4, 10-11 records the transaction:

And Abraham rose up from before his dead, and spoke unto the children of Heth, saying: ‘I am a stranger and a sojourner with you: give me a possession of a burying-place with you, that I may bury my dead … and Ephron the Hittite answered Abraham in the hearing of the children of Heth, even of all that went in at the gate of his city, saying: ‘Nay, my lord, hear me: the field give I thee, and the cave that is therein, I give it thee; in the presence of the sons of my people give I it thee; bury thy dead.’

The traditional location of this burial site is known today as the Cave of the Patriarchs. Around 2,000 years ago, King Herod built a large commemorative structure around the site, which was later turned into a mosque. This Herodian building is believed to be the oldest, intact, continuously used prayer structure in the world.

Many key events in the lives of the patriarchs occurred at Hebron. Abraham built an altar there. Sarah died there. Isaac lived there. It was from here that Jacob sent his son Joseph to check on his other sons—a journey that led Joseph into Egyptian captivity, and one from which only his bones returned after many hundreds of years, carried back by the Israelites during the Exodus out of Egypt.

Canaanite Hebron

After Abraham’s time, Hebron continued to function as a thriving Canaanite community, operating under the authority of the wider Egyptian regional power (as did virtually all of the Canaanite city-states). Sometime during the middle of the second millennium b.c.e., though—the time of the Exodus—Hebron’s power dropped off dramatically. This is evident from the archaeological record at Tel Rumeida and also a series of tablets known as the Amarna Letters. (And also from the Bible.)

The Amarna Letters are a trove of documents found at ancient Amarna in Egypt, dating to the 14th century b.c.e. The “letters”—or rather, clay tablets—are the desperate correspondence from leaders of Canaan to Egypt’s pharaoh, asking urgently for help against the invading “Habiru” nomads that were taking over the land. The linguistic similarities between Habiru and Hebrew are tantalizingly similar—and the dating of the letters fits the general time frame of the Israelites entry into the Promised Land. (These Habiru are also known as Hapiru or ‘Apiru.)

There is some debate about whether any of these “letters” came from Hebron. Whether this is the case or not, it is certain that Hebron was caught up in this region-wide upheaval as the invading Habiru conquered the land. The Bible describes just this event—and that the king of Hebron was killed while taking part in an offensive against the Israelites. The Hebrews later arrived at Hebron itself, and utterly destroyed the city and the inhabitants. The Bible also describes the presence of giants in the area of Hebron. While no remains of giants have yet been found, remains of massive cyclopean buildings have. “Cyclopean masonry” is the building of structures using massive boulders, named after the legendary Greek giants. These stones used at Canaanite Hebron—some of which weighed more than 10 tons apiece—made up a city wall and towers. One damaged tower is preserved up to 20 feet high—originally, it was probably much taller.

Despite the strength of Hebron, it was successfully destroyed and taken over by Caleb, one of the righteous spies that had originally searched out the land of Canaan. Remains of destruction of this Canaanite city have been found. Caleb was a chief Judahite patriarch, and the territory became a part of the tribe of Judah.

Archaeological remains show that following this time period, Hebron was indeed occupied by Israelite inhabitants. The township remained a steady size for the next few centuries, not reaching its zenith until the 11th–10th centuries b.c.e. This was the time that David grew up in the area.

Hebron—Genesis of a Kingdom

It was in the rolling Hebron countryside that David raised his father’s sheep. And fittingly, this was to be the first capital city of David. After Saul died, elders of Judah congregated in Hebron to anoint him king. Hebron became the first capital city of David. (It wasn’t until 7½ years later that the rest of Israel accepted David as king, and he established Jerusalem as his capital city.) David would have raised up Hebron to new heights of prominence as his first capital. This shows up in the archaeological record.

It is not surprising that David’s son Absalom attempted to reign from Hebron during his uprising. It seems that he wanted to usurp his father by rooting himself to Judah’s “first city,” the same way David’s rule had been established in Hebron decades before. Hebron, for better or worse, was a city intimately connected to David’s family. And according to tradition, the tomb of David’s father, Jesse, is located on the summit of the tel.

Nearly 200 years after David’s time, Hebron reappears in the archaeological record as a powerful and significant city. This is reflected in the lmlk seal impressions.

lmlk seals were stamps on the handles of official vessels used during the reign of King Hezekiah. The handles bear the inscription lmlk, Hebrew for “Belonging to the king.” lmlk handles have a central motif positioned below the inscription. There are two main versions of the central motif: either a four-winged scarab or a two-winged sun. It is common for handles to have a second inscription below the central motif. This secondary inscription names one of four Judean cities: Hebron, Socoh, Ziph and Mmst (an unknown word). This shows the importance of Hebron during the reign of Hezekiah (end of the eighth-century b.c.e.). While well over 2,000 of these stamped handles have been found, the reason for their use is unknown. Various theories include taxation methods and special preparation for the Assyrian siege.

Excavations at Hebron have revealed that the city was destroyed and abandoned in 586 b.c.e. in the face of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonian invasion—supporting the biblical record.

Hebron Today

After its destruction by the Babylonians and continuing to the modern day, Hebron witnessed repeated banishment of and repopulation by Jews. The 20th century, though, witnessed a significant change.

During the start of the century, Jews and Arabs coexisted peacefully in the city. In 1929, that all changed. Arab crowds, incited by the Mufti and under the illusion that the Jews were planning to take the Temple Mount, entered the homes of Jewish residents and began slaughtering Jews en masse. Sixty-seven people were massacred. British forces evacuated the remaining 400-plus Jews. The horrific incident was considered by one historian to be “year zero of the Arab-Israeli conflict,” and it was a significant impetus for the proper establishment of an Israeli Army, known today as the Israel Defense Forces.

The city came under total Jewish control during the 1967 Six-Day War. In 1993, however, governance of all areas of the West Bank was turned over to the Palestinian Authority as part of the Oslo Accords changed. With one exception.

Hebron, with such a rich significant history and heavy population of (very zealous) Jews, was the limit. In 1997, the city was split into two sections: H1, a Palestinian-controlled zone, and H2, an Israeli-controlled zone. The years since have seen the city continue as a flashpoint location, a site of terrorist activities on both sides. It’s ironic that the “friend” city, the city made famous by a patriarch so revered by both Jews and Muslims, the sacred burial site of the forefathers, has become such a bloodbath. In another sense, the city’s current status is just a continuation of the primal sin—for according to tradition, it was here that the world’s first murder was committed: the slaying of Abel by his brother Cain.

This article is one in a series on biblically significant cities whose histories have been uncovered through archaeology. Take a look at our articles about Lachish, Tel Dan, Gezer, Khirbet Qeiyafa, and Jerusalem to uncover more of this biblical history for yourself.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer