In the eighth century b.c.e., Azekah acted as one of the first major bulwarks against Assyrian King Sennacherib’s campaign against the Kingdom of Judah. 2 Kings 18:3 tells us that when Sennacherib attacked, he came up “against all the fortified cities of Judah, and took them.” Sennacherib himself wrote about his siege and capture of this biblical city in the Azekah Inscription: “The city of Azekah … I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated ….”

Defenders of this fortress city helplessly watched as the Assyrians built their signature siege ramp. All efforts by the Judahites to stop their progress were to no avail. The Assyrians took the city and plundered its treasures before moving on to the next major city in its sights: Lachish. Its main target: Jerusalem.

Archaeologists have found abundant evidence of the Assyrian conquest at Lachish. Depictions of the siege were recorded on large slabs at Sennacherib’s palace, today known as the Lachish wall reliefs. The Assyrian siege ramp at this location was found (the earliest one, to that point, ever discovered) along with several arrowheads and weapons used by the invading army.

Archaeological excavations at Tel Azekah have gone on for years. Archaeological evidence has allowed the positive identification of the site as Azekah, thanks to discoveries such as the Azekah Inscription. Still, evidence of a destruction from this period of Assyrian invasion has been limited. One problem is that Tel Azekah is so elevated that most of the arrowheads and other signs of war have most likely washed away by now.

Over the summer of 2020, however, archaeologists led by Tel Aviv University archaeologist Prof. Oded Lipschits uncovered traces of a siege ramp dating to the time of the Assyrian invasion at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. The discovery of this siege ramp validates the accuracy of the Assyrian and biblical accounts of Sennacherib’s conquest.

An Assyrian Siege Ramp

When Professor Lipschits and his team began digging in the southeastern corner of the tel, they were perplexed by what they found: a mess of Canaanite remains just below, yet some 1,000 years older than, the Judahite. As they continued digging, however, they discovered that these remains were actually part of an original, huge outer Bronze Age wall that surrounded the city, one that had been partially dismantled and repurposed to create a 45-degree angle siege ramp up the side of the inner eighth century Judahite wall.

Using the Canaanite remains to assemble the ramp would have saved a lot of time and effort for the Assyrians—especially considering that the city was located on such a steep hill. (The sheer height and impressiveness of the city is partially demonstrated by the photo below.)

Buried within the fill at the bottom of the Azekah ramp, two Assyrian ritual chalices were discovered, likewise dating to the same time period (and akin to similar chalices depicted on Assyrian reliefs).

City of Canaan, City of Judah

Anciently, cities were typically built around four basic prerequisites: access to water, trade routes, arable land and fortification. If a city was in a great strategic location, its history would often stretch on for centuries or millennia—one civilization building on top of another—thus creating a large artificial mound—a “tel.” Such was the case with Tel Azekah, only contributing to its impressive height. This tel guarded the strategic Elah Valley.

The Canaanite construction of the site—including their above-mentioned wall that stood some six meters high—dates to around 1700 b.c.e., and their occupation continued for several hundred years. The Bible testifies to the existence of Azekah during Joshua’s conquest of Canaan: Israel had formed a league with Gibeon, and Joshua and the Israelites came to its aid in fighting off attacking Amorites. Those attackers who were not slaughtered were chased back to their cities Azekah and Makkedah. Additionally, God rained down giant hailstones on the fleeing Amorites at Azekah (Joshua 10:10-11).

In a journal publishing their findings, archaeologists analyzing Tel Azekah concluded that the cities Azekah and Lachish were some of the most powerful cities in the southern Shephlah in the 12th century b.c.e. These cities, however, “fell victim to devastation, either by an unknown aggressor or from a natural disaster” during this century. Following this destruction, Azekah and Lachish apparently remained in ruins for several centuries.

2 Chronicles 11 lists a number of cities rebuilt by King Rehoboam, including Azekah and Lachish (verse 9). Archaeological evidence at the site shows that Azekah was finally completed sometime around the ninth century b.c.e.

By the time of King Hezekiah in the late eighth century b.c.e., it was a major defensive city.

The Azekah Inscription

In the mid-eighth century b.c.e., the Middle East came to be dominated by the Neo-Assyrian empire. The northern kingdom of Israel was successively invaded and taken captive by the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser iii, Shalmaneser v and Sargon ii. Some few years later, at the end of the eighth century, the Assyrians returned to attack Judah, this time under the control of King Sennacherib. Their return was to put down a rebellion in which several kingdoms in the Levant, including King Hezekiah’s Judah, had refused to pay taxes to the Assyrian king, and had apparently allied with Egypt (2 Kings 18:7, 21; Isaiah 30).

After conquering the Philistine city-states along the coast, the Assyrians turned their attention eastward toward Judah. King Sennacherib’s army moved swiftly. Sennacherib’s prism inscriptions state that he conquered 46 fortified cities of Judah in less than 12 months—that’s almost one per week.

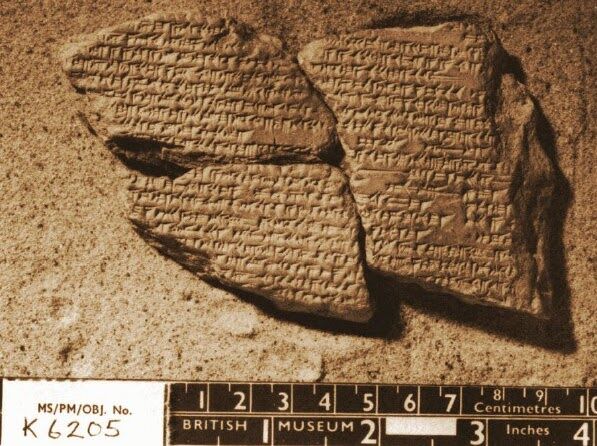

As the Assyrians approached this colossal city, the task at hand would have seemed at least somewhat daunting to the everyday soldier. To Sennacherib, however, conquering this city meant a tremendous victory, one he boasted about in his Azekah Inscription (heavily damaged, yet still understandable):

The city of Azekah … located on a mountain ridge, like pointed iron daggers without number reaching high to heaven. [Its walls] were strong and rivaled the highest mountains… [by means of beaten (earth) ra]mps, battering rams … I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated … they had seen [the approach of my cav]alry, and they had heard the roar of the mighty troops of the god Ashur, and [their] he[arts] became afraid … [The city Azekah I besieged,] I captured, I carried off its spoil, I destroyed, I devastated, [I burned with fire] …

This doesn’t sound like your average run-of-the-mill city. For this and other reasons, the city has been referred to as Judah’s “third” great city—after Jerusalem and Lachish (the three are also listed in Jeremiah 34:7). Conquering this city was impressive feat, one that we now have proof of.

To Be Built Again

After conquering Azekah and Lachish, Sennacherib moved on to Jerusalem, besieging the city and trapping King Hezekiah “like a bird in a cage.” By a miracle, Jerusalem did not fall to Assyria—and Sennacherib returned to Nineveh, conspicuously omitting any mentioned of defeating Jerusalem alongside the cities of Azekah and Lachish.

Azekah was rebuilt a few decades after the Assyrian onslaught, but as Jeremiah 34:7 records, it was once again destroyed in the early sixth century b.c.e., when the Babylonians conquered Judah and destroyed Jerusalem.

All was not lost for this Judahite city, though. Nehemiah records that Azekah was again rebuilt and reoccupied when the people returned from Babylonian exile (Nehemiah 11:30), adding more layers to the site’s rich history.

As archaeological excavations continue to go deeper into the layers of earth, more exciting finds are uncovered—and subsequently more evidence of the historical record is revealed. This exciting discovery of the siege ramp at Azekah adds to the growing body of evidence of the overwhelming Assyrian siege of Judah in the eighth century b.c.e., as described in the Bible—when Sennacherib came up “against all the fortified cities of Judah” (2 Kings 18:13).