Among biblical civilizations, the Samaritans are the “odd one out.” Other peoples, like the Moabites and Assyrians, readily trace their descent to a patriarchal ancestor from immediately after the Flood or during the patriarchal age. Most biblical civilizations started off pretty early. The Samaritans, in contrast, don’t have a lineage tracing back to a single ancestor, and they appear quite late in the biblical account. And while other civilizations’ religions were completely different from that of the Israelites, the Samaritan religion was a mish-mash of Israelite and pagan practices.

Who Are the Samaritans?

The Samaritans see themselves as descendants of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, and their priesthood as the descendants of Levi. According to their traditions, it was during the time of the high priest Eli that the separation occurred. Eli was an elderly high priest with corrupt sons. By allowing his sons to profane the priesthood, Eli essentially presided over the degeneration of Israel’s religion (1 Samuel 2:12—as per the Hebrew Bible, proper worship was eventually restored under the Prophet Samuel, called by God for such a purpose—1 Samuel 3:19-21).

According to the Samaritan version of events, Eli was a false high priest from an illegitimate line that intentionally deceived the southern Israelites—the tribe of Judah. There was a conflict between Eli and the legitimate priesthood, so the legend goes, which culminated in a split between the northern 10 tribes and the Jews. According to the Samaritans, this all occurred before the reign of King David; while the northern tribes kept the true faith, the Jews changed customs and “degenerated” into what they essentially are today.

Because of this, the Samaritans only accept the first five books of the Bible, the Torah, as authoritative—and even then, there are significant differences. Subsequent books set and written from the “split” onward belong to a deceived Jewish populace (the first books following the Torah, for example—Joshua, Judges and Ruth—are traditionally associated with the Prophet Samuel).

Samaria Before the Samaritans

The Bible has a diametrically opposite account—namely, that the Samaritans are not Israelites at all. But before we can understand these Samaritans specifically, we have to understand the civilization preceding them: the northern kingdom of Israel. The Bible relates that the 12 tribes were unified and even reached their zenith during the 10th-century b.c.e. reigns of David and Solomon (see here for archaeological evidence relating to this). But it records a dramatic split occurring following the death of Solomon, at the start of Rehoboam’s reign. 1 Kings 12 records how the northern 10 tribes split off from the house of David, based in Jerusalem, as a result of oppressive rule. They chose as king the successful administrator Jeroboam, an Ephraimite (1 Kings 11:26; 12:20).

Jeroboam was ordained king over the 10 tribes by God (1 Kings 11:31). But he feared that if Israel continued worshiping as commanded at God’s temple in Jerusalem, they would return to Jerusalem’s rule. So he made two golden calves and placed them in the cities of Bethel and Dan, telling the people: “Ye have gone up long enough to Jerusalem; behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt” (1 Kings 12:28).

Jeroboam also instituted a new sacrificial system echoing the one described in the Torah; for example, he created a festival in the eighth month, counterfeiting the Sukkot festival in the seventh month (verse 32). In other words, Jeroboam’s religion was a paganized counterfeit of God’s true religion, with a specific emphasis on shunning Jerusalem.

Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a massive altar and ritual platform in Dan, complementing what is described for the northern kingdom in the Nevi’im (the Prophets portion of the Hebrew Bible, which the Samaritans reject). It meanwhile conflicts with the Samaritans’ view that they had one altar in Mount Gerizim (more on this further down).

A later king, Omri, “bought the hill Samaria of Shemer … and he built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, after the name of Shemer, the owner of the hill, Samaria” (1 Kings 16:24). This would be the northern kingdom’s new capital city, and it would eventually give its name to the whole region—and later, the Samaritan community.

Enter Assyria

The years 721 b.c.e. to 718 b.c.e. are critical. This is when Assyria’s kings Shalmaneser v and Sargon ii conquered the Israelites and deported them east of Mesopotamia (2 Kings 17:6; 18:9-11). To lessen the likelihood of future unrest, and to cauterize any connections with the land, the Assyrians conducted a massive population swap. They deported the Israelites and replaced them with other conquered peoples from their empire. Who were the people brought in? According to 2 Kings 17:24:

And the king of Assyria brought men from Babylon, and from Cuthah, and from Avva, and from Hamath and Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel; and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof.

These, then, became the biblical ancestors of the Samaritans. This conglomeration of various groups would mix together and form one identity.

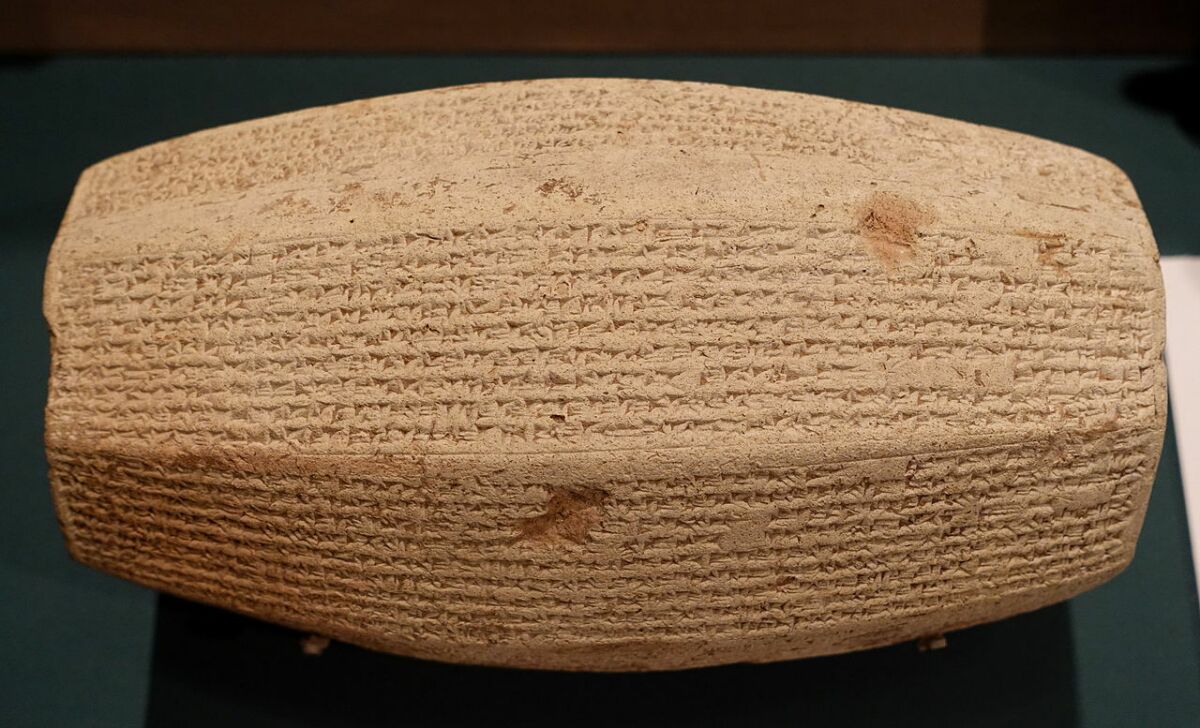

This Assyrian deportation and resettlement is recorded in archaeology. Sargon ii called himself “conqueror of Samaria and of the entire country of Israel” in his annals. He reported sending in other peoples to replace the Israelites he deported. His annals could be the earliest extra-biblical account of the Samaritans.

Here are some selected quotes from Sargon’s annals, following his successes and ultimate defeat of the capital city itself (the remainder of the country had since fallen in earlier campaigns):

I surrounded (and) conquered the city Samaria. I carried off as booty 27,290 of its inhabitants. …

(As for) the … faraway Arabs who live in the desert, (who) did not know (either) overseer (or) commander, and had never brought their tribute to any king, I struck them down with the sword of the god Ashur, my lord, deported the remainder of them, and (re)settled (them) in the city of Samaria.

(As for) the people of [(the city) Sa]maria who had [altogeth]er come to an agreement with a king [hostile to] me … I foug[ht] them [and] counted [as] booty 47,280 people, together with [their] chariots and the gods who helped them. I conscripted two hundred chariots from among them into [my] royal (military) contingent and settled the remainder of them in Assyria. I restored the city of Samaria and made (it) greater than before. I brought there people from the lands that I had conquered. I set a eunuch of mine as provincial governor over them and considered them as people of Assyria.

Interestingly enough, the Bible records a Samaritan governor of the region being in league with a prominent Arab (see Nehemiah 2:19).

The Assyrian annals confirm the biblical account of both Israel’s deportation out of the Holy Land and the repopulation of the region with Gentile foreigners.

Beyond the Assyrian inscriptions, the archaeological record in the land of Samaria itself also attests to the importation of Mesopotamian peoples. Around this archaeological period, a new Babylonian material culture appears. Cuneiform writing appears in various cities in the region, including Samaria itself. Locally made bowls and other vessels made in Babylonian styles have been dug up. And an Assyrian cuneiform stele set up by Sargon has been found in Ashdod (a Philistine city), attesting to the region as an Assyrian province.

An Age-Old Rivalry

At this juncture, the Bible describes the establishment of a quasi-Jewish religion among the new population.

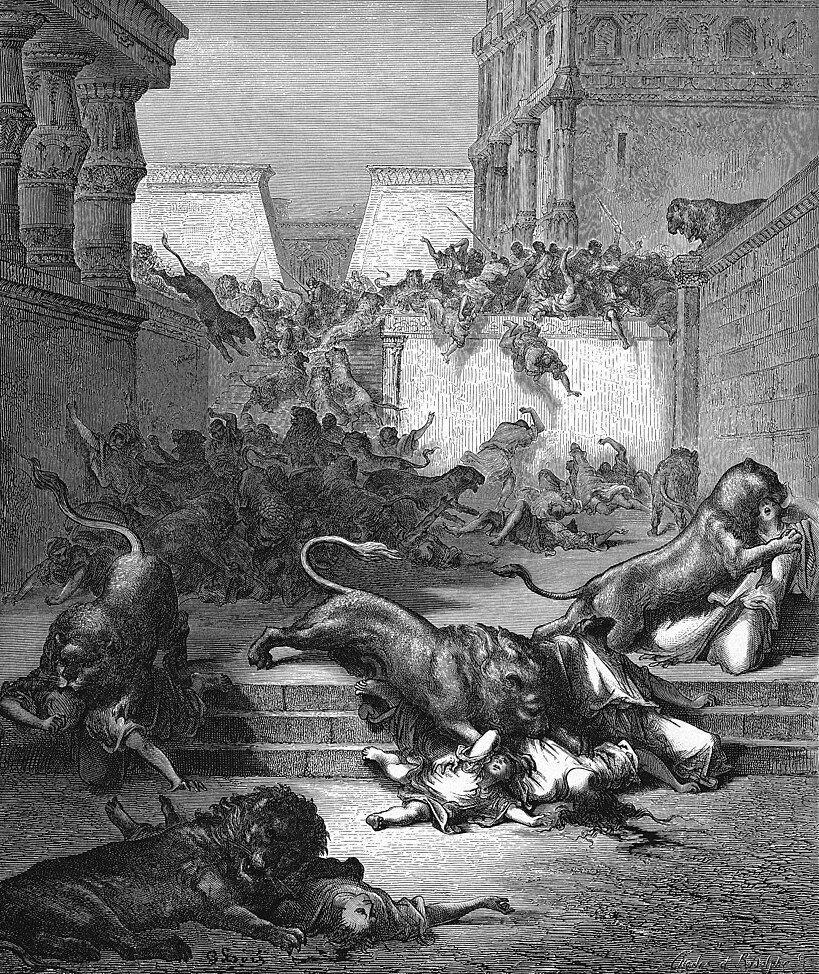

“And so it was, at the beginning of their dwelling there, that they feared not the Lord; therefore the Lord sent lions among them, which killed some of them. Wherefore they spoke to the king of Assyria, saying: “‘The nations which thou hast carried away, and placed in the cities of Samaria, know not the manner of the God of the land; therefore He hath sent lions among them, and, behold, they slay them, because they know not the manner of the God of the land’” (2 Kings 17:25-26).

The king of Assyria then sent one of the priests of Jeroboam’s counterfeit religion back to Samaria. He was to teach the new inhabitants how to worship God—Jeroboam’s way. The Samaritans blended the priest’s instructions with the religious traditions of their homelands (verses 27-33). What resulted was a religious conglomeration of Babylonian and Jeroboamite practices. There was some superficial resemblance to how God was worshiped in Judah (verse 32), but it was only superficial.

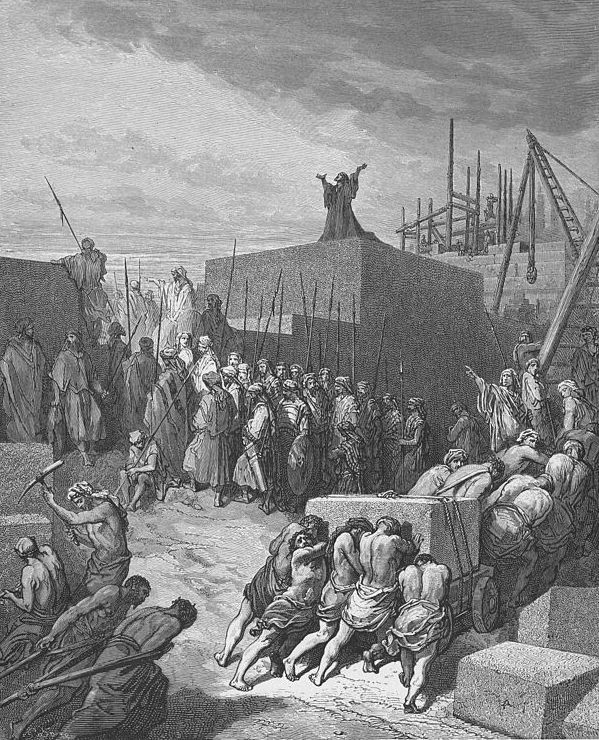

The next time the Samaritans appear in the biblical account is during the Persian period. A century after the Israelites were deported, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon conquered the Jews and deported them to Mesopotamia, like their Israelite brothers earlier—although the deportation was not as thorough (and there was not an import of foreign peoples). Also unlike the Israelites, the Jews were allowed to return once Cyrus of Persia conquered Babylon (2 Chronicles 36:22-23). The Samaritans weren’t pleased with their return.

“Now when the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin heard that the children of the captivity were building a temple unto the Lord, the God of Israel; then they drew near to Zerubbabel, and to the heads of fathers’ houses, and said unto them: ‘Let us build with you; for we seek your God, as ye do; and we do sacrifice unto Him since the days of Esarhaddon king of Assyria, who brought us up hither.’ But Zerubbabel, and Jeshua, and the rest of the heads of the fathers’ houses of Israel, said unto them: ‘Ye have nothing to do with us to build a house unto our God; but we ourselves together will build unto the Lord, the God of Israel, as king Cyrus the king of Persia hath commanded us’” (Ezra 4:1-3).

The Samaritans didn’t take this rejection lightly. They caused trouble for the Jews during the reigns of the Persian kings Cyrus and Darius (verses 4-5). During the reigns of the kings Xerxes (Ahasuerus) and Artaxerxes, they even petitioned the kings to stop the reconstruction (verses 6-16). In their letter to Artaxerxes, they acknowledged that they were deported from their homeland to Israel by Assyria. This time, they claimed that it was the Assyrian King Asenappar (Ashurbanipal) that brought them there (verse 10). Artaxerxes acknowledged the letter as coming from the people “that dwell in Samaria” (verse 17)

In other words, between Shalmaneser, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, Samaria was populated by multiple peoples from different deportations under different Assyrian kings. This diversified their population significantly.

Ezra wasn’t the only Jew of the Persian period who had trouble with the Samaritans: Nehemiah’s main Samaritan adversary was the governor of Samaria, Sanballat the Horonite (Nehemiah 2:10). Sanballat and his co-conspirators attempted to violently stop the reconstruction of Jerusalem (Nehemiah 4:1-2). That plot failed, but it didn’t stop Sanballat from trying to harm Nehemiah in the future (Nehemiah 6:1-3). After Nehemiah left Judah for a brief period, Sanballat convinced the son of the Jewish high priest to marry his daughter—a forbidden act (Nehemiah 13:28; Leviticus 21:14). Once Nehemiah returned, he took care of the problem by casting the priest’s son out.

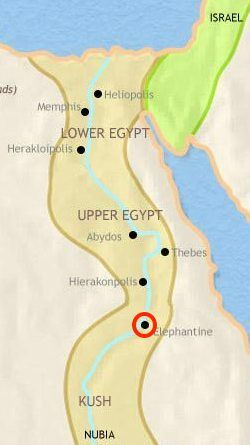

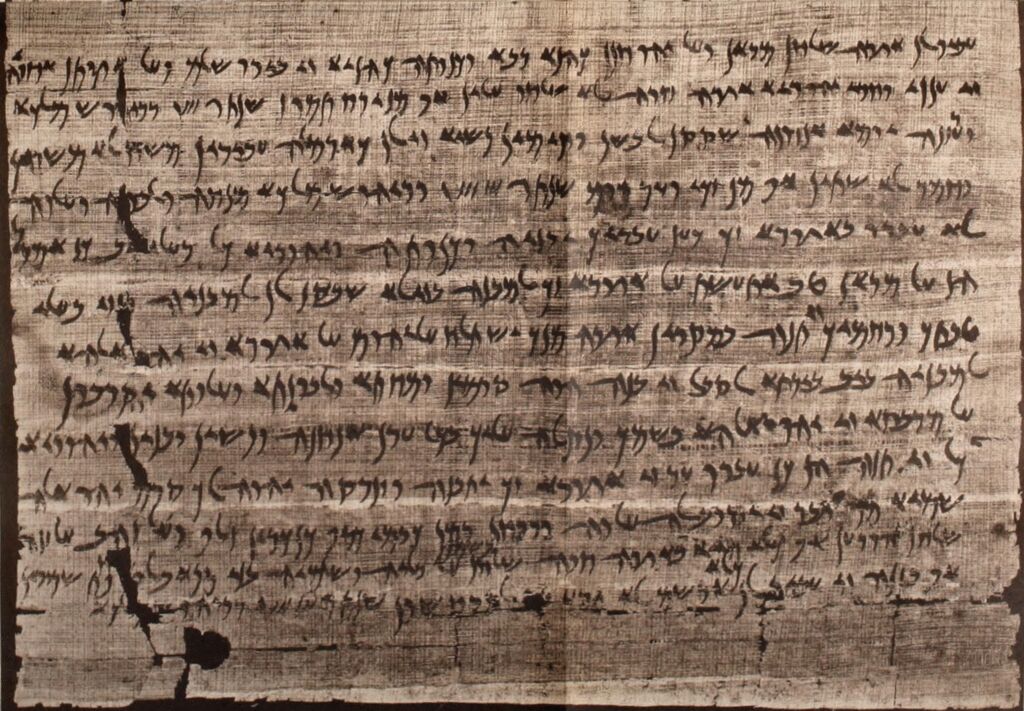

The archaeological record confirms Sanballat’s existence. Up the Nile River, deep in Egyptian territory, lies the island of Elephantine. A Jewish colony existed there since the times of the pharaohs. This colony continued into the Persian Empire. Archaeologists in 1909 discovered a papyrus letter from Elephantine written by the Jewish community there. It was supposed to be sent to Jerusalem but evidently never made it off the island. This letter references “Sanballat, governor of Samaria.” Sanballat must certainly have been a prominent official if such a southern island community in Egypt knew his name.

Also, a portion of Nehemiah’s wall has been discovered by archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar. She uncovered a fortifying Persian-period wall making up part of Jerusalem’s fortification system, with evidence of hasty construction and finds associated with this specific part of the Persian period. The fact that the wall was hastily and loosely constructed suggests that the Jews were expecting an imminent attack. At first glance, biblical account aside, that would seem strange considering the Jews were under Persian rule for centuries, meaning they didn’t have control over their own country and therefore didn’t stage their own wars—the Persians were responsible for the territory. The Persians were also relatively benevolent rulers and had good relations with the Jews. But an imminent attack from another people within the Persian Empire, like the Samaritans, makes sense. You can read more about the discovery of Nehemiah’s wall here.

A New Temple

The account of the Hebrew Bible leaves off there, but this isn’t the end of the conflict between the Jews and the Samaritans. After Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, both Judah and Samaria became provinces of Egypt under the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty. The Samaritans staged an uprising against Alexander’s governor and murdered him. Alexander’s troops subsequently occupied Samaria. Amid the unrest, the Samaritans migrated out of the city looking for a new capital.

They found one in Mount Gerizim.

Again, unlike in Judaism, Samaritanism only accepts the Torah as inspired scripture. Many scholars consider Ezra to be the man responsible for the canonization of most of the Hebrew Bible. Given the Samaritans’ friction with the Jews at the time of Ezra, their rejection of the Bible at large isn’t surprising.

Jerusalem’s prominence in the Hebrew Bible comes mainly from the city serving as David’s capital. The city isn’t mentioned as prominently in the Torah (though its significance is shown in the book of Genesis). This would have given the Samaritans extra incentive to find a central place of worship aside from Jerusalem.

Moses wrote the book of Deuteronomy as his last instructions to the Israelites before they entered the Promised Land. He instructed the Israelites to give a blessing upon Mount Gerizim (as well as a curse upon Mount Ebal) after they entered Canaan (Deuteronomy 11:29). This is most likely where the Samaritans got their idea that Mount Gerizim was a sacred place.

The ruins of Mount Gerizim have been excavated since the 1960s. While there are scant remains today, what is still around is impressive. Two different sites on Mount Gerizim are identified with the Samaritan temple. The first one, lower on the mountain, has a courtyard 41 meters wide (about 135 feet). R.G. Bull, the archaeologist who first excavated the temple, identified this courtyard with the location of the Samaritan sacrificial altar. There is controversy about whether this first site is the actual Samaritan temple or a later Greek temple or something else.

Another potential spot is located higher up the mountain, as identified by archaeologist Yitzhak Magen. His excavations, uninterrupted from 1982 to 2000, revealed a building divided into three parts, as well as an altar and burnt bones. According to Magen, “The temple’s orientation is similar to that of the temple in Jerusalem … the temple itself faced east, the altar stood in the eastern part of the precinct, between the temple and the eastern gate, and the Holy of Holies stood near the western wall.”

The Samaritan temple itself actually attests to the Jewish narrative of the origin of the Samaritans: In the Samaritan Torah, the 10th Commandment, “Thou shall not covet,” is replaced with a commandment to build an altar on Mount Gerizim. Yet the archaeological record of the Mount Gerizim temple doesn’t go beyond the Hellenistic (Greek) period. The dating of Moses’s writing of the Torah is over a thousand years before this time. It’s true that the Samaritan commandments specifically mention an altar, rather than a temple. But that the Samaritans would wait so long to build a temple after the commandment was given is certainly implicative of the later founding of the religion.

Into the New Testament

Evidently, the animosity between Jews and Samaritans lasted past the Greek era and into the Roman Empire. The Christian New Testament records this tension. A couple of episodes from Jesus’s ministry stand out: In one instance, Jesus and his disciples were making their way from Galilee to Jerusalem. They had to pass through Samaria, and sent messengers to a Samaritan village on the route to prepare for him. Luke 9:53 states, “And they [the Samaritans] did not receive him [Jesus], because his face was as though he would go to Jerusalem” (King James Version). The Jerusalem–Mount Gerizim dispute by this point had become so contentious that the Samaritans wouldn’t even let Jews enter their cities.

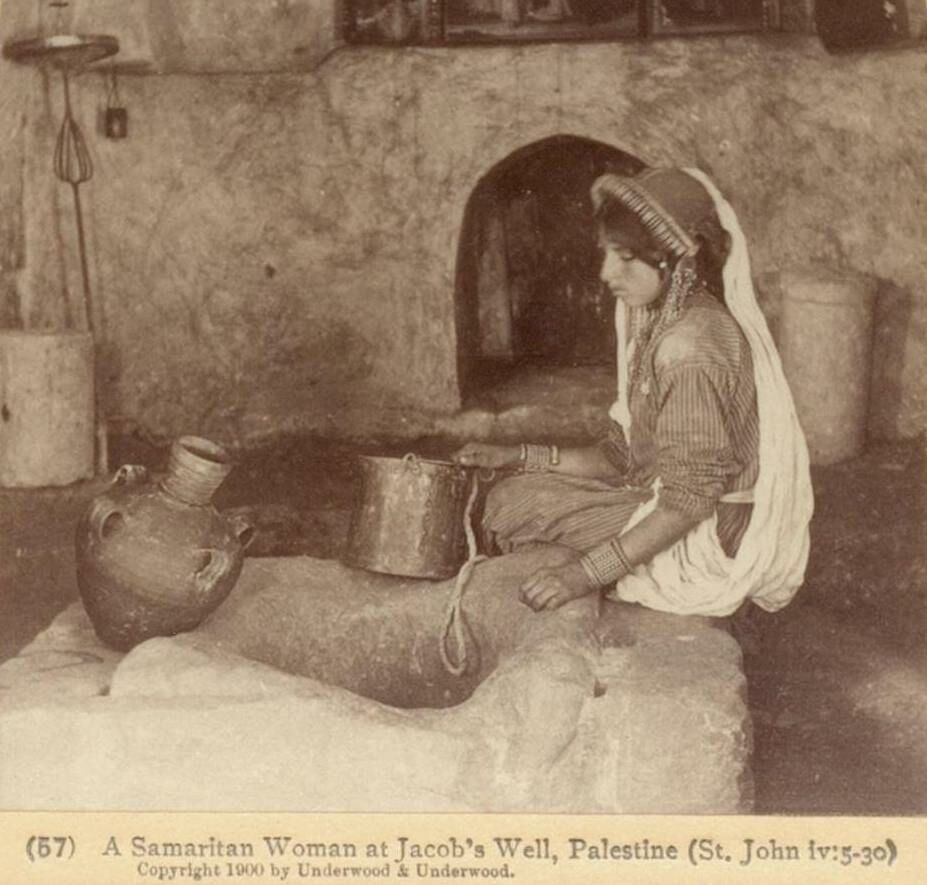

This is also represented in another New Testament passage. In John 4, Jesus visited Sychar, a Samaritan city. He sat by a well dug by the patriarch Jacob (which, according to Jewish, Christian, Samaritan and Muslim tradition, has been identified with a site now occupied by a Greek Orthodox Church). A Samaritan woman came to fetch water, and Jesus asked her to share some with him (verse 7). The Samaritan woman asked, “How is it that thou, being a Jew, askest drink of me, which am a woman of Samaria? for the Jews have no dealings with the Samaritans” (verse 8). The woman also acknowledged the Samaritans’ worship at Mount Gerizim (verse 20).

But what about the city of Samaria itself? When the Romans accepted Herod as ruler over Judea, Emperor Augustus granted Samaria to him. Herod, in gratitude to his patron, bulldozed the city’s Greek and Israelite architecture and reconstructed it on a Roman model. He renamed the city Sebaste, a derivative of Sebastos, the Greek equivalent of Augustus. The Roman city featured a forum, basilica, aqueduct, stadium, theater and massive temple dedicated to the emperor.

The New Testament records Samaria’s history of rank paganism as well. Acts 8 speaks of a sorcerer named Simon who “bewitched the people of Samaria, giving out that himself was some great one: To whom they all [the people of Samaria] gave heed, from the least to the greatest, saying, This man is the great power of God” (verses 9-10). This passage specifically records Simon asking to purchase from Peter an equivalent rank as the apostle (verses 14-19; the word “power” can also be translated as “authority”). Peter rebuked Simon and his offer: “For I perceive that thou art in the gall of bitterness, and in the bond of iniquity” (verse 23). This statement is a quote of Deuteronomy 29:16-18—a direct reference to those who attempt to introduce pagan practices into the national religion.

Simon the sorcerer didn’t end his work in Samaria. In a letter to Emperor Antoninus Pius, Justin Martyr wrote, “There was a Samaritan, Simon … who in the reign of Claudius Caesar, and in your royal city of Rome, did mighty acts of magic, by virtue of the art of the devils operating in him. He was considered a god, and as a god was honored by with a statute … on the river Tiber, between the two bridges, and bore this inscription … ‘Simoni Deo Sancto,’ ‘To Simon the holy god.’” Justin Martyr wrote in his First Apology about the doctrines of Simon’s emerging sect. His followers called themselves Christian but worshiped a different god. As far as the Romans were concerned, they couldn’t distinguish between actual Christians and Simon’s sect. Justin Martyr singled out one of their main doctrines as the belief of man’s immortality. (This “counterfeit”-themed religion harkens back to the time of the Assyrian deportation, as well as the Jeroboam secession.)

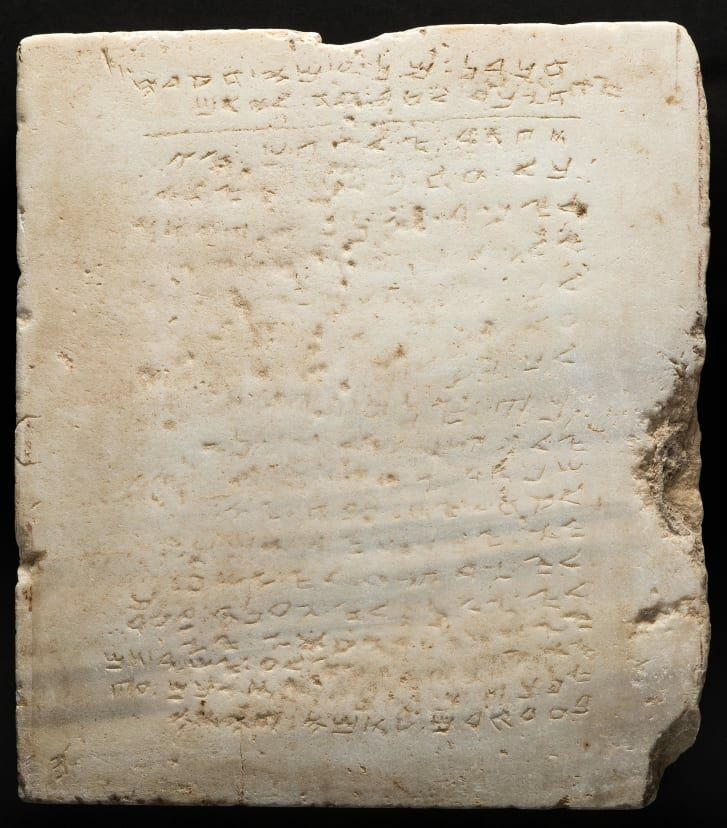

Samaria continued to be inhabited as a Roman and later Byzantine city. But the Samaritan culture continued. The oldest inscription of the Ten Commandments, at 1,500 years old, is from a Samaritan synagogue during this time. This is based off of the Samaritan Torah, however. The Tenth Commandment was replaced by the command to “raise up a temple” on Mount Gerizim.

During the Crusades, Samaria was exchanged between Crusader and Muslim forces. Today, Samaria lies in ruins.

Samaritans Today

But that doesn’t mean the Samaritans didn’t survive. They have small numbers—818 as of last year—but they still exist. They live mostly around Mount Gerizim in the West Bank as well as suburban Tel Aviv. They still have their own synagogues, Torah, priesthood and religious services. They speak Hebrew today and have assimilated into Israeli society. The intense hostility between Jerusalem and Mount Gerizim may be over, but they’re still proudly Samaritan.

What are some things that distinguish Samaritans from Jews? Unlike Jews, which have multiple rabbinates, the Samaritan priesthood is centralized, with only one high priest ruling. They also perform animal sacrifices, something the Jews stopped practicing two millennia ago. Samaritan women isolate during menstruation and immediately after childbirth, as per the Torah. Samaritans forbid intermarriage among other groups. This, given their small numbers, has decreased their gene pool—and some Samaritan men have responded to this by importing formerly Christian brides from Ukraine.

The Samaritans may be small in number, but they’re still around. And when one considers how the Romans couldn’t distinguish between actual Christians and the Samaritan Simon’s religion, and then considers some of the tenets of his faith—the immortality of the soul, a “moved” religious headquarters in Rome, priests forgiving people on behalf of God—the Samaritans’ religion has certainly left its mark on Western civilization.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Samaritans