The Great Flood is one of the most well-known accounts in the Bible. It has been the subject of everything from Bible classes to nighttime stories to immense research and heated debate. It has stirred numerous expeditions to find the Ark. Some consider the Flood a historically accurate event. Many others consider it a fable that has been perpetuated for millennia.

Yet perhaps not so many realize that the story of the Great Flood is not limited to the Bible.

Taking the Bible literally means believing that the Great Flood was not a regional event. It means believing that the floodwater covered the entire Earth. “And I, behold, I do bring the flood of waters upon the earth, to destroy all flesh, wherein is the breath of life, from under heaven; every thing that is in the earth shall perish. … every living substance that I have made will I blot out from off the face of the earth” (Genesis 6:17, 7:4). Aside from Noah, his family, the animals inside the ark and any aquatic animals surviving the floodwaters, this was a worldwide destruction that wiped out everything “under heaven.” So the Bible does not describe a regional flood.

“And the waters prevailed, and increased greatly upon the earth; and the ark went upon the face of the waters. And the waters prevailed exceedingly upon the earth; and all the high mountains that were under the whole heaven were covered. … [A]nd Noah only was left, and they that were with him in the ark” (verses 18-19, 23).

This was a globe-covering catastrophe. This is important to establish, for if such a worldwide event occurred affecting all human life, it should be expected that the ensuing generations would have their own memories, records and legends of this enormous event. And remarkably, this is exactly what we find, all around the world. Various descriptions of a great, cataclysmic ancient flood are common around the world. These common ideas point to a common root event. The account of the flood is not just found among the Israelites, who came on the scene some 700 years after the floodwaters receded. Examining the accounts of other sources from other cultures tells us a lot about the reliability of the Bible record.

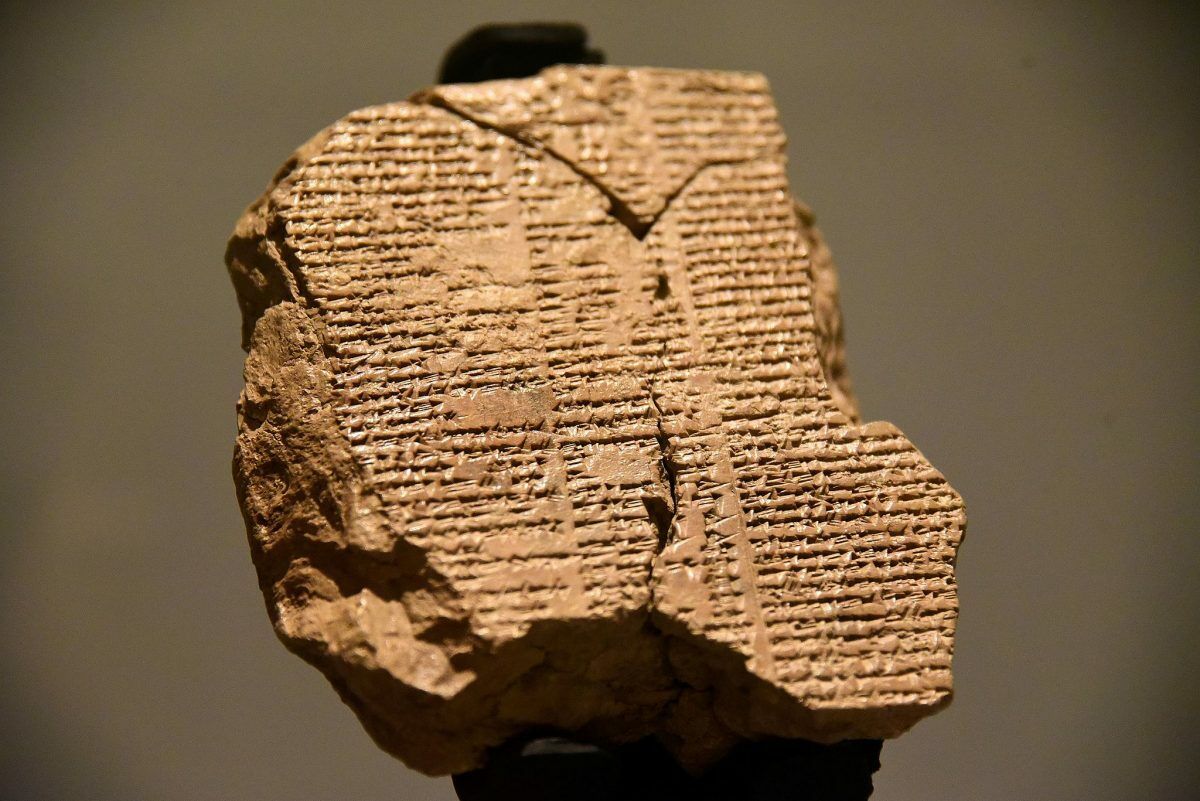

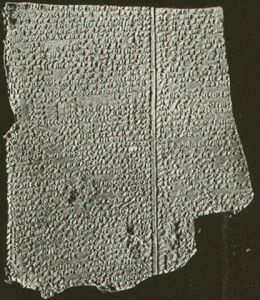

The Epic of Gilgamesh is probably the most famous extra-biblical Flood account. It is found on a series of tablets from the ancient city of Sumeria. The most complete tablets date to around 650 b.c.e., but these are known to be copies from more ancient tablets (parts of which have been found), dating to around 2,000 b.c.e. In turn, these 4,000-year-old tablets are themselves thought to have been sourced from even older material. Chronologically, this puts the Sumerian account quite close to the time of the flood that the Bible indicates.

The Epic of Gilgamesh describes a Noah-like figure named Utnapishtim. According to the epic, Utnapishtim built a boat within which he, his relatives, and all species of animals survived a flood that destroyed all mankind. Like the Bible account, Gilgamesh states that the reason for the flood was human wickedness. Like the Bible account, the large boat came to rest on a mountain. Both accounts describe birds being released to test whether the water had sufficiently subsided. In fact, both accounts describe the use of the same bird species, the dove and the raven. Both accounts record that sacrifices were offered after the flood, and both records say that the men (Utnapishtim, Noah), were afterward blessed.

Gilgamesh differs from the Bible account in a number of ways, but the similarities as described above are too striking to overlook.

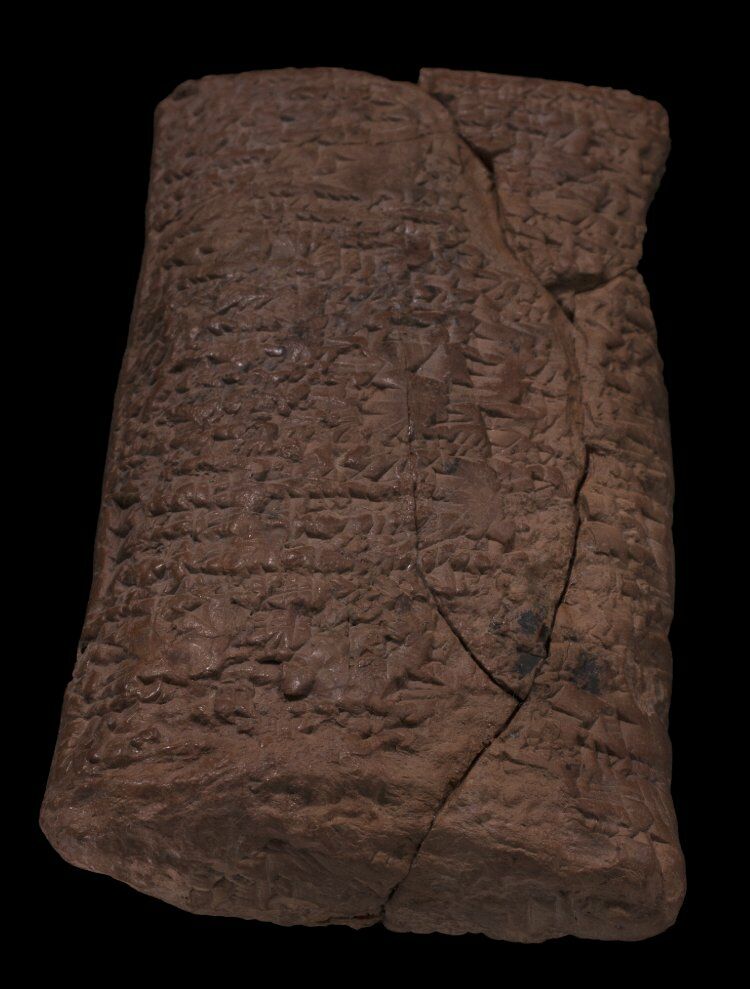

Another ancient account of a Great Flood is the Babylonian Ark Tablet. This dates to around 1900-1700 b.c.e. The god described on this tablet instructed Atra-hasis to build a boat for himself and the animals to survive an imminent flood. It also specifically states that the animals entered the boat two-by-two. The Bible records the identical fact: the animals boarded in pairs (Genesis 7:2, 8-9). The Ark Tablet also differs from the Bible account (for instance, describing the boat as perfectly round in shape), yet the commonality with the Bible is remarkable.

There is the Greek myth of Deucalion. The myth states that after human beings were created, they disobeyed the gods. It was decided that they should be destroyed. The righteous Deucalion and his wife were spared in an ark from the flood that destroyed mankind. Deucalion’s ark landed on a mountain, and after surviving the flood, he offered sacrifices. Interestingly, Deucalion’s great-grandson was Ion. Ion compares to Noah’s grandson Javan, whose name is actually spelled with the Hebrew letters I/E, O, N.

The ancient Chinese told many myths about floods, some describing the waters as “reaching heaven.” In some of these legends, the main character is a female named Nüwa (a strikingly similar name to Noah). She repopulates the Earth and repairs the broken heavens. In imagery invoking the rainbow of Genesis, Nüwa patches the damaged sky by smelting stones of five colors. Then there’s the Hindu tale of Manu, who is warned about a flood and builds a boat to contain the seeds of life with which to repopulate the Earth. His boat, tugged by a fish, comes to rest on a mountaintop, and Manu performs a sacrifice. You can read further of Irish and Welsh flood myths, Finnish and Norse blood-deluge myths, numerous African flood myths, Pacific flood myths and ancient American flood myths.

This begs the question: How did all of these completely different peoples, all over the globe, get the same general—and sometimes very specific—ideas?

In “Why Does Nearly Every Culture Have a Tradition of a Global Flood?,“ John Morris, Ph.D., describes his collection and analysis of more than 200 accounts of floods, originally reported by missionaries, anthropologists and ethnologists. He writes:

While the differences are not always trivial, the common essence of the stories is instructive, as compiled below:

- Is there a favored family? 88%

- Were they forewarned? 66%

- Is flood due to wickedness of man? 66%

- Is catastrophe only a flood? 95%

- Was flood global? 95%

- Is survival due to a boat? 70%

- Were animals also saved? 67%

- Did animals play any part? 73%

- Did survivors land on a mountain? 57%

- Was the geography local? 82%

- Were birds sent out? 35%

- Was the rainbow mentioned? 7%

- Did survivors offer a sacrifice? 13%

- Were specifically eight persons saved? 9%

Morris concludes his article by writing:

The only credible way to understand the widespread, similar flood legends is to recognize that all people living today, even though separated geographically, linguistically, and culturally, have descended from the few real people who survived a real global flood, on a real boat which eventually landed on a real mountain. Their descendants now fill the globe, never to forget the real event.

The deduction is straightforward and sound. A common idea points to a common experience. And the concept of a Great Flood must be one of the most common in human history. Many scoff at the biblical story of a Great Flood. Yet its account has been preserved by so many ancient civilizations right around the Earth. Dismissal of this event out of hand would be either naïve or intellectually dishonest. What must have happened to trigger the recording of such stories? Perhaps a great worldwide flood really did happen—one that would have thus left a significant historical and cultural mark on all mankind afterwards—not just the Israelites. And if the Bible is right about the Great Flood, what else is it right about?