They tamed the high seas centuries before the Vikings and the buccaneers. They rode elephants while the rest of the world was riding horses. They were the world’s luxury craftsmen long before the Swiss were making watches. Who were they?

The Phoenicians, an ancient civilization located in modern-day Lebanon and northern Israel, are credited with some remarkable achievements. Yet we know surprisingly little about them today. The purported inventors of the alphabet left us very few texts. And they didn’t leave us any giant structures littered with vivid writings and images that preserve their story, like Egypt’s pyramids.

There is, however, one too easily forgotten and too easily ignored literary source that can fill in at least some of the gaps in our understanding of the Phoenicians: the Hebrew Bible.

The Bible reveals fascinating details about Phoenician civilization. But beyond that, it also explains one of the primary reasons this civilization flourished. A significant part of the Phoenicians’ success can be attributed to their relationship with Israel!

The Bible shows that the Phoenicians were, for better or worse, one of Israel’s longest and most steadfast allies. This partnership lasted centuries and impacted both civilizations, allowing both nations to experience their golden age at the same time.

Phoenician Background

The common name “Phoenicia” comes from the ancient Greeks. Homer wrote in the Iliad of fine craftsmanship that “far exceeded all others in the whole world for beauty; it was the work of cunning artificers in Sidon, and had been brought into port by Phoenicians.”

Scholars estimate the Iliad was written sometime during the eighth century b.c.e. Homer’s is among the earliest references we have to Phoenicians in Western literature, and it associates them with the production and trade of luxury goods. A hallmark of ancient Phoenician culture is high-quality craftsmanship and skill in commerce.

The root word for “Phoenician” is the Greek phoinikē, meaning “red.” There are two general theories as to why the Greeks called them “red men.” One is that the Phoenicians’ complexion was thought of as “red” to the Greeks. The other associates the name with the famed dye produced in the region.

While it is inconclusive what the Phoenicians called themselves, many scholars believe they went by the same name the Bible gives them: Canaanites.

The Canaanites were a conglomeration of Semitic-speaking peoples who inhabited the Levant from southern Israel to the northern coast of Syria. When Israel left the wilderness and marched into the land of Canaan in the 15th century b.c.e., it wiped out many of the southern Canaanite populations. But the Bible records that certain groups survived and continued to live alongside Israel, with some regions, particularly in the north, remaining untouched by Israel.

It’s also interesting to note that the word “Canaanite” in biblical Hebrew means “merchant,” lending further credence that the Phoenicians are Canaanites.

The first biblical reference to the Phoenicians is in Genesis 10: “And Canaan begot Zidon his firstborn, and Heth” (verse 15). “Zidon” is an archaic spelling of Sidon, one of the major Phoenician city-states of the region. (Other known Phoenician city-states include Tyre, Byblos and Beirut, Lebanon’s capital city.)

The Phoenicians were never ruled as one “empire,” and historians do not consider them a vast dominion or kingdom. Rather than being identified as a common culture or people, the Bible (as well as Greek literature) identifies the early Phoenicians according to the city-state they belonged to. Sidon/Zidon and Tyre are the two main cities referenced in the Hebrew Bible. (The Septuagint—the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible—sometimes translates the expression “land of Canaan” as “Phoenicia.”)

What made the Phoenicians different from other Canaanites?

The Phoenician Exception

It is clear from the biblical text that Phoenicia’s chief cities of Tyre and Zidon actually fell within the borders of Israel, specifically the territory belonging to the tribe of Asher.

God intended much of what is modern Lebanon to be part of the original allotment for the 12 tribes of Israel. Joshua 11:8 describes the Israelites chasing Canaanite armies “unto great Zidon.” Joshua 19 describes the territorial boundaries for the tribe of Asher, which would include the following cities: “Rehob, and Hammon, and Kanah, even unto great Zidon; And then the coast turneth to Ramah, and to the strong city Tyre …” (verses 28-29; King James Version). References to “great Zidon” and “the strong city Tyre” demonstrate how powerful these two key Phoenician cities were compared to the other Canaanite entities in the late Bronze/Early Iron Age (c. 1400–1050 b.c.e.).

But Israel never followed through on God’s command to conquer this territory. Judges 1:31-32 record: “Asher drove not out the inhabitants of Acco, nor the inhabitants of Zidon, nor of Ahlab, nor of Achzib, nor of Helbah, nor of Aphik, nor of Rehob; but the Asherites dwelt among the Canaanites, the inhabitants of the land; for they did not drive them out.”

Judges 3 states something similar: “Now these are the nations which the Lord left … namely, the five lords of the Philistines, and all the Canaanites, and the Zidonians, and the Hivites that dwelt in mount Lebanon, from mount Baal-hermon unto the entrance of Hamath” (verses 1, 3).

Historical sources, archaeology and the Bible all show that, as the world transitioned from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, both the Israelites and the Phoenicians entered a golden age. Is it coincidence that both peoples—allies and neighbors—thrived at exactly the same time?

‘Ever a Lover of David’

During the mid-to-late-11th century b.c.e., Israel consolidated into what is called the united kingdom. After the turbulent reign of King Saul, King David not only secured Israel’s frontiers but expanded them. Regions that David subjugated include Philistia (1 Chronicles 18:1); Ammon and Edom, situated in modern-day Jordan and Southern Israel (2 Samuel 12:26-30; 1 Chronicles 18:12); and the Syrians (2 Samuel 8:5-6; kjv).

There was, however, one region that David did not touch.

Far from going to war with each other, David’s Israel and the Phoenicians, specifically Tyre, formed a robust alliance. 2 Samuel 5:11 shows that Tyre’s King Hiram sent diplomats to King David to construct him a palace. He also supplied cedar wood, carpenters and masons. 2 Samuel 24:7 includes Tyre in the census David commissioned Joab to undertake, suggesting that Tyre was a friendly vassal kingdom or some sort of junior partner to Israel. 1 Kings 5:1 even states that “Hiram was ever a lover of David.”

Using the Bible as her guide, late archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar uncovered the foundations of King David’s Phoenician-constructed palace.

Visit the City of David today and you will see two gigantic structures. First, there’s the 10th-century b.c.e. Large Stone Structure, the palace itself; then there’s the structure that buttresses it, called the Stepped Stone Structure. The Stepped Stone Structure filled in a large void in the bedrock just north of the Jebusite citadel, allowing the Large Stone Structure to be built atop and adjoining the citadel. Various scriptures reference the palace of David in relation to a stepped structure, as well as the high northern edge of the existing citadel.

One of the notable remains at the City of David site is a Phoenician-style column capital, now on display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. It is specifically named a “proto-Aeolic capital.” Some of our readers may be familiar with different Greco-Roman capital styles: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. The proto-Aeolic style was in use long prior to the Greco-Roman, and the name refers to the style of two curved palm leaf-like spirals. This particular design is associated with Solomon’s temple in 1 Kings 6:35. This capital was built by Phoenician craftsmen, and it testifies to the biblical account of King Hiram building David’s palace in Jerusalem.

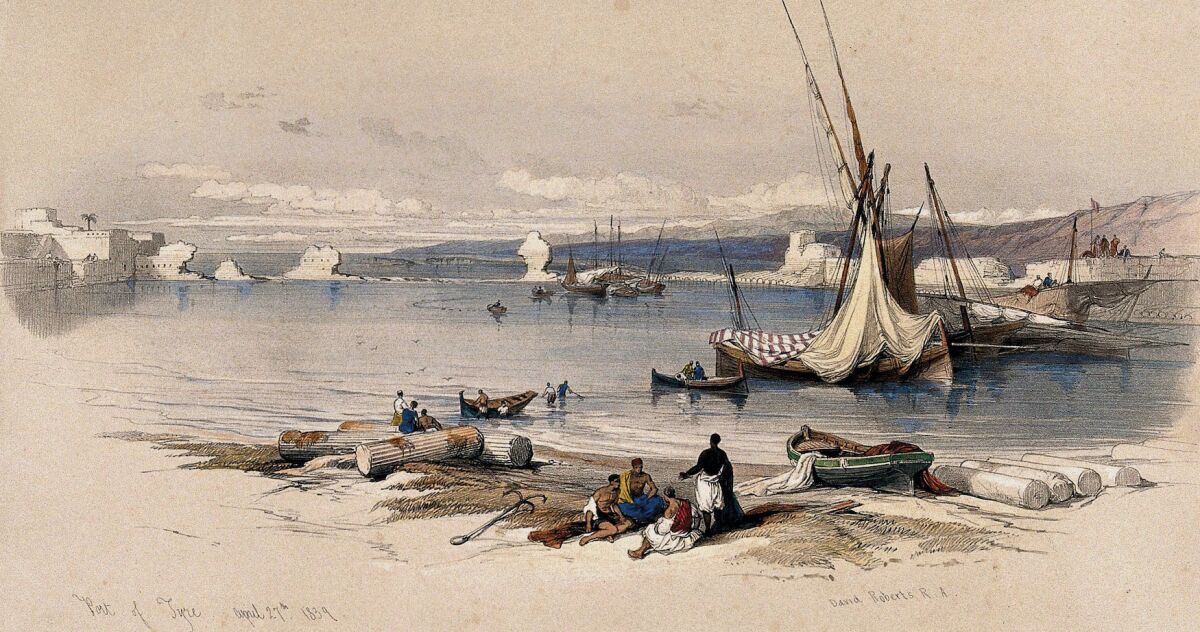

The Bible also specifically states that King Hiram sent David cedar wood for the palace. Lebanon, then and now, was famed for its trees. The cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) can today be found growing natively in Lebanon, Israel, Syria, Turkey and Cyprus. These trees grow up to 35 meters (about 114 feet) tall. Their wood has been used in construction since ancient times. Cedar wood is especially prized for boat building; it is highly durable, easy to shape and mold, and resistant to deterioration in seawater. The so-called “Jesus boat”—a remarkably preserved 2,000-year-old vessel found submerged in the Sea of Galilee and now exhibited in the Yigal Alon Museum in Israel—was made partially from cedar of Lebanon. Having such an abundant supply of quality wood so close to home surely was one of the reasons the Phoenicians were able to become such skilled sailors.

King Solomon and Tyre

The friendship between Israel and Phoenicia, especially Tyre, continued after David’s death (2 Chronicles 2:2). 1 Kings 5 shows that King Hiram sent a delegation to congratulate King Solomon on his coronation. We also know that Solomon hired the Tyrians to send cedar wood for construction of God’s temple (2 Chronicles 2:7, 15).

Solomon’s request of Hiram in 1 Kings 5:15 is interesting: “Now therefore command thou that they hew me cedar-trees out of Lebanon; and my servants shall be with thy servants; and I will give thee hire for thy servants according to all that thou shalt say; for thou knowest that there is not among us any that hath skill to hew timber like unto the Zidonians.” This implies that either Tyre had some sort of control over Zidon, or that “Zidonian” was a generic term for Phoenicians in general. This could indicate that, by this point, the Phoenicians were acquiring their own cultural identity separate from the rest of the Canaanites.

When Hiram sent cedar timber to Israel, he did so by boat (verse 23). The Phoenician technique of shipping cedar wood to their clients is well documented. A wall relief from the palace of Assyrian King Sargon ii (displayed in the Louvre in Paris) shows Phoenician sailors transporting large quantities of logs from a port across the sea.

2 Chronicles 2:3 and 6 reveal another interesting detail: King Solomon requested King Hiram supply a workman who was skilled in working with “purple” dye for the construction of the temple. The Phoenicians were known for their near-monopoly on the production of purple dye, also known as Tyrian purple. They harvested the dye from the murex shellfish, a sea snail with natural purple coloring that thrived off the coast of Lebanon.

Tyrian purple was a highly valued luxury for a long time; the fourth century c.e. Roman Emperor Diocletian, in his Edict of Maximum Prices, lists 1 pound of the dye as costing 150,000 denarii, three times the value of gold. Only the richest in society could afford Tyrian purple. This is why, today, we associate the color purple with royalty.

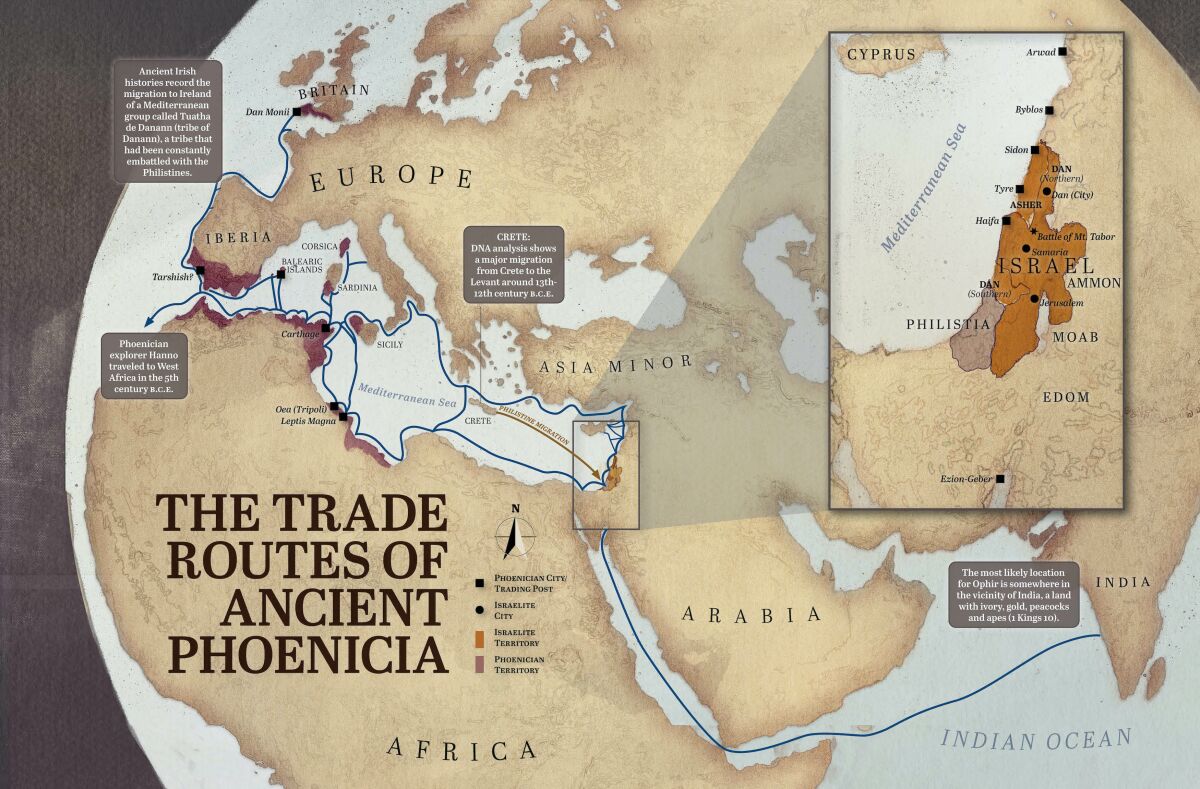

The Bible also records that Solomon and Hiram collaborated on establishing Israel’s navy. 1 Kings 9:26-28 state that Solomon enlisted Hiram to set up a navy at Ezion-geber, an ancient port on the Red Sea (near the modern city of Eilat). From that port, the Israelite-Phoenician navy undertook missions sailing to the land of Ophir, famed for its gold reserves. An ostracon (a pottery shard with writing on it) discovered in Israel in 1946 actually makes mention of this mysterious foreign land; the inscription reads: “Ophir gold to Bet Horon: 30 shekels.” The most likely location for Ophir is somewhere in the vicinity of present-day India.

Phoenician explorers making it to India may sound far-fetched. But Greek historian Herodotus and Roman author Pliny the Elder both recorded that the Phoenicians were such skilled sailors that they could circumnavigate Africa. If the Phoenicians built ships with Israel in Ezion-geber, they would have set sail from the Gulf of Aqaba and accessed the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea.

The Carthaginian (Phoenician) explorer Hanno sailed to West Africa in the fifth century b.c.e., possibly as far south as Cameroon. Hanno mentions in the text Periplus seeing a volcanic eruption that some scholars identify with Mount Cameroon. He also claimed to encounter a race of aggressive, hairy beings who climbed trees and fought by biting and throwing stones, which may be a reference to either chimpanzees or gorillas. (It is interesting to note that one exotic import Solomon acquired from his navy was, according to 2 Chronicles 9:21, apes.)

As for Phoenicia’s King Hiram, archaeology has affirmed his name was in use during the 10th century b.c.e. A royal sarcophagus from that time was discovered at the Phoenician city of Byblos bearing the words “Ahiram, King of Byblos.” The Bible does specify Hiram as “king of Tyre,” so the sarcophagus may belong to another king (Byblos was situated further north along the coast). But it is possible the site was under King Hiram’s jurisdiction within wider Phoenicia. Further, there is biblical evidence of crossover in Phoenician regional names, given that Solomon refers to the Tyrian Hiram’s people as “Zidonians” (1 Kings 5:20).

The reigns of David and Solomon represent the pinnacle of Israelite-Phoenician relations. Following the death of these two kings, relations between their peoples remained cordial. But Israel’s close ties with Phoenicia came with a cost.

Queen Jezebel’s Connection

The unity of the kingdom under David and Solomon did not last. After Solomon’s death, 10 of the 12 tribes split from the government in Jerusalem and formed their own kingdom, based in the north. Under its inaugural king, Jeroboam, the northern kingdom quickly rejected God. This made Israel more susceptible to foreign influence, which reached an apex under the notorious King Ahab due to his wife, Queen Jezebel.

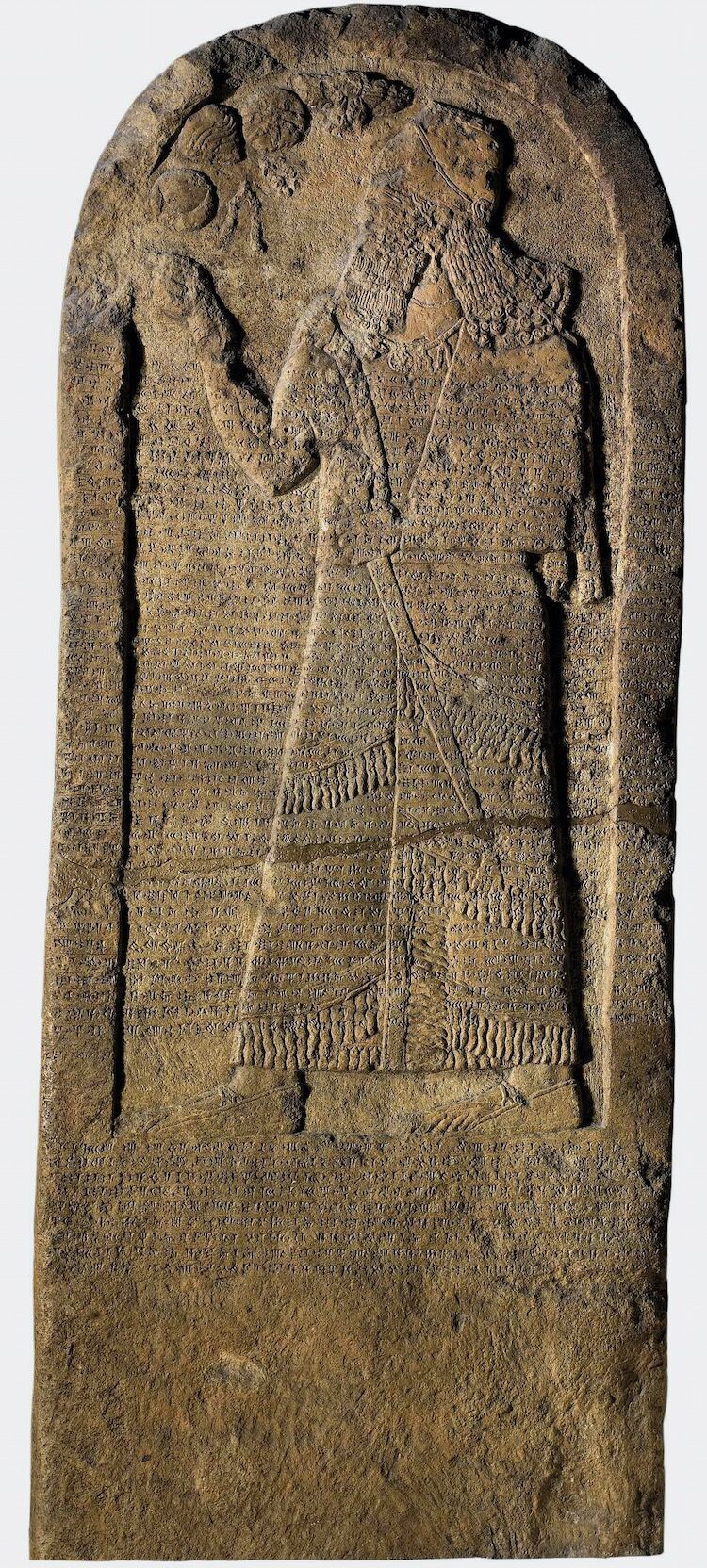

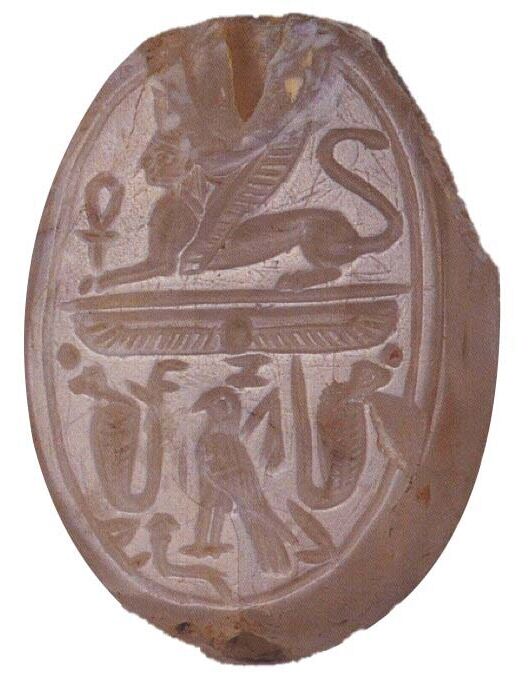

Today, we have archaeological evidence of both Ahab and Jezebel. The Kurkh Monolith, an Assyrian victory stele currently in the British Museum, references Ahab possessing a powerful fighting force. And in 1964, a seal was made public from a private collection. The seal’s slightly damaged Phoenician inscription, surrounded by Phoenician-style motifs reads: [l’]yzbl, “[Belonging to J]ezebel.”

1 Kings 16:30-33 say specifically that Jezebel was “the daughter of Ethbaal king of the Zidonians,” notably different from “king of Zidon.” In similar form, the first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus calls Ethbaal “king of the Tyrians and Sidonians.” This implies that “Zidonian” was a name used for Phoenicians in general, beyond the inhabitants of the single city of Zidon.

Additionally, Ethbaal’s name has been confirmed as a Tyrian royal name. Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser iii described in his Iran Stele an “Ethbaal” ruling over Tyre. This would have been a different Ethbaal from Jezebel’s father as it dates to the following century. It does, nonetheless, attest to the prevalence of the name.

The Bible condemns Ahab for his obsession with paganism, but it specifically points to Jezebel’s influence as the cause. The Bible says Jezebel introduced (or rather, reintroduced) Baal worship into Israel. The Canaanites were notorious for Baal worship (Judges 2:11-13). But Jezebel is noted for the scale of her worship: The Bible describes her having 450 prophets of Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah (also known as Ishtar or Ashtaroth, Baal’s consort) within her entourage (1 Kings 18:19). Aside from being an affront against the God of Israel, this pagan Phoenician worship was especially offensive because of the institution of child sacrifice (Jeremiah 19:5).

Scholars previously disputed whether or not Baal worshipers actually practiced child sacrifice. Some claimed the references to child sacrifice were an attempt by biblical authors to disparage other religions. But today there is significant archaeological evidence for the barbaric rite. While Baal was worshiped throughout the ancient Middle East, the most compelling evidence for child sacrifice comes from the Phoenicians—specifically, Phoenician Carthage, situated in modern-day Tunisia.

Greco-Roman writers wrote that the Carthaginians sacrificed their children. For example, in his dialogue Minos, Plato wrote: “With us [the Greeks], for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos.”

The ruins of Phoenician Carthage hold many “tophets”—burial grounds for infants. Scholars previously thought that these were ordinary cemeteries for infants, but recent analysis challenges this interpretation. Many of the graves are topped by a plaque describing the deceased being dedicated to the gods. Some of the plaques end by stating the deities “heard my voice and blessed me.” Additionally, most of the bodies were cremated, as specifically attested to in the Bible. (Stillborn or otherwise unhealthy babies wouldn’t have been considered a good offering to the gods.) The children were mostly about the same age: a few weeks old.

Also, the remains of animals, “beyond question sacrificial offerings,” according to Dr. Josephine Quinn, were buried among the children in the tophets—sometimes even together with infant remains in urns.

The tophets apparently don’t identify the specific gods the children were sacrificed to. However, the Greeks and Romans state that the Carthaginians sacrificed their children to “Cronos,” “Cronus” or “Kronos,” a Greek deity identified with Baal. And Baal worship in Carthage is evident from the name of Carthage’s most famous son: the General Hannibal (“Baal is gracious”), who famously fought Rome with an army riding on elephants.

The Bible identifies the sin of Baal worship as one of the main reasons God allowed the northern 10 tribes to be conquered by Assyria. “For she [Israel] did not know that it was I that gave her The corn, and the wine, and the oil, And multiplied unto her silver and gold, Which they used for Baal. … And now will I uncover her shame in the sight of her lovers, And none shall deliver her out of My hand” (Hosea 2:10, 12).

The Phoenicians’ religious influence, and especially that of the Phoenician Queen Jezebel, was a primary reason for Israel going into captivity. But what goes around comes around. As Israel fell, so would Tyre.

The Prince of Tyre

Phoenicia’s friendship with the Israelites didn’t last forever. Ezekiel the prophet lived during the late seventh and early sixth centuries b.c.e. and was taken captive by the Babylonians during their conquest of the kingdom of Judah. Ezekiel wrote of Tyre’s opposition to the kingdom of Judah and even how it sought to conquer its territory. Because of this, Ezekiel prophesied that Tyre would fall at the hands of the Babylonians (Ezekiel 26:1-4, 7).

Why did Tyre so eagerly eye Jerusalem?

According to Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews, the king of Tyre at the time of Nebuchadnezzar’s conquests in the Levant was Ethbaal iii. God did not have many good things to say about Ethbaal. In Ezekiel 28, the prophet refers to Ethbaal as the “prince of Tyre.” (It’s important to note, verse 11 switches to refer to Satan as “king of Tyre,” the real power behind the throne.)

God condemned King Ethbaal for his hubris; the passage says Ethbaal’s “heart is lifted up, And [he] hast said: I am a god, I sit in the seat of God, In the heart of the seas” (verse 2). God calls him wiser than the Prophet Daniel, with “no secret” hidden from him (verse 3). Through “wisdom” and “discernment,” Ethbaal procured “gold and silver Into [his] treasures” (verse 4). God tells Ethbaal that his “heart is lifted up because of thy riches” (verse 5).

But as God says, “Yet thou art man, and not God” (verse 2). He then pronounces judgment on the king: “Therefore thus saith the Lord God: Because thou has set thy heart As the heart of God; Therefore, behold, I will bring strangers upon thee, The terrible of the nations …” (verses 6-7).

The prophecy identifies Tyre’s geographic location in “the heart of the seas.” This is more than merely a reference to Tyre’s coastal location. Tyre, at this time, was actually two different cities that operated as one: There was the original port city, situated on the mainland, and there was the newer city, which was built on an artificial island, and served as the main trade hub. Unlike other cities in the ancient world—even other coastal cities—this city of Tyre was surrounded by water on all sides. It was literally, as Ezekiel recorded, “in the heart of the seas.”

What did Ezekiel mean when he said Ethbaal iii called himself a “god” and sat “in the seat of god”?

The god worshiped at Tyre was Melqart, meaning “king of the city.” Melqart was synchronized by later Greek writers with Herakles, or Hercules. Some identify Melqart as another title for Baal. According to The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean, “he is the Iron Age heir of the ancient Syro-Palestinian tradition of deceased deified kings ….” Melqart’s temple hasn’t been identified, but Greek writer Herodotus, referring to Melqart as the Greek hero Herakles, writes that the temple was magnificent in its day and “richly equipped with … offerings.” Among the centerpieces of the temple’s treasures were two pillars, one made of refined gold and the other of emerald.

As the name “king of the city” implies, Melqart was heavily associated with Tyre’s monarchy. World History Encyclopedia states, “Melqart was considered by the Phoenicians to represent the monarchy, perhaps the king even represented the god, or vice versa, so that the two became one and the same.” The kings of Tyre were even known by a similar title, mlk-qrt.

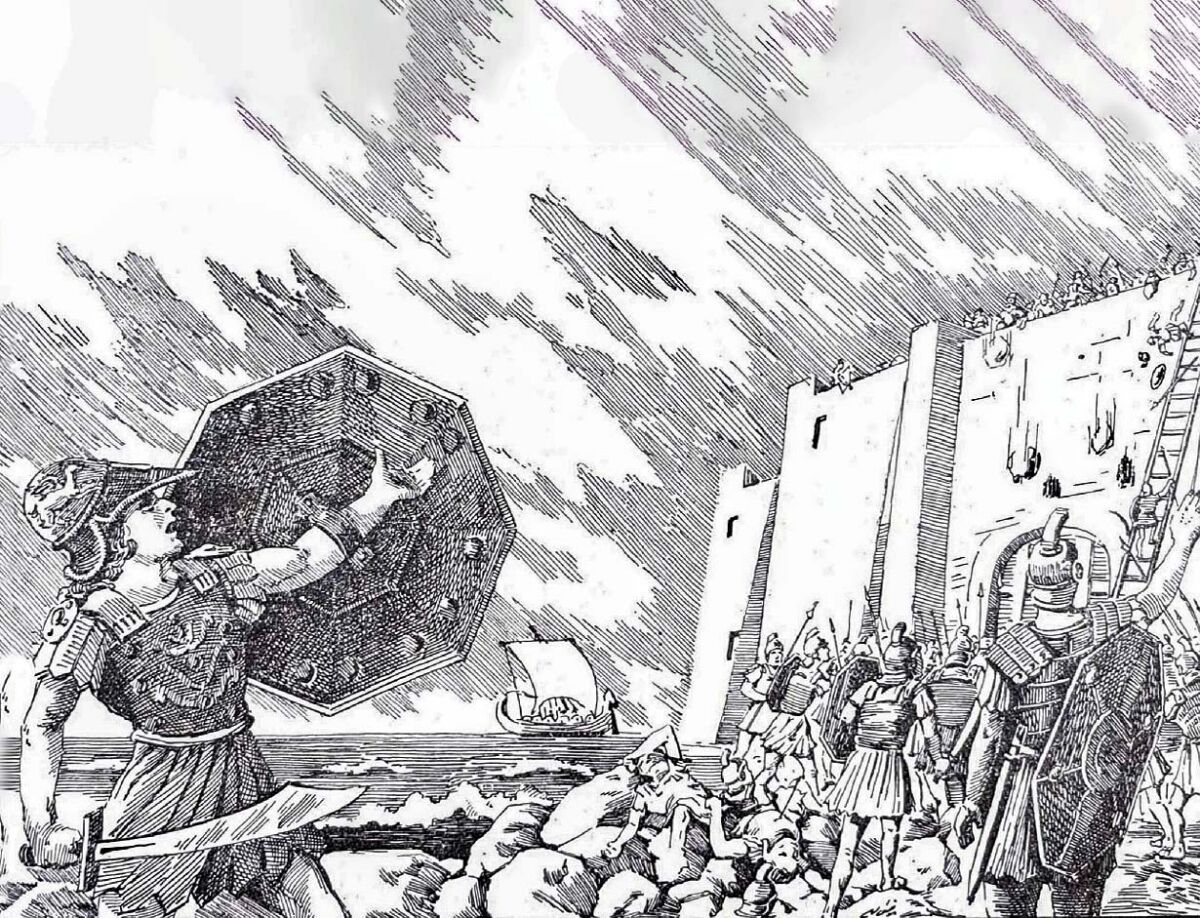

The prophecy in Ezekiel of Tyre’s defeat was ultimately fulfilled. The Babylonians laid siege to Tyre for 13 years, according to Josephus. Cuneiform tablets confirm that Nebuchadnezzar conquered the city. His massive army pulverized the mainland city; due to the Babylonians’ lack of a navy, the island portion of the city remained. But centuries later, Alexander the Great finally conquered all of Tyre. Using the ruins of the old city, he built a causeway to reach the island and besieged it. To this day, over 2,000 years later, Alexander’s causeway still connects the island city with the mainland.

The Big Lesson

The alliance between Israel and the Phoenicians is unique in the Bible. Few of Israel’s neighbors were as supportive of Israel as the Phoenicians. And using the Bible together with archaeology, it becomes apparent that Phoenician history is Israelite history. Israel and Tyre reached their golden ages at the same time, with kings from both nations willing to work together to accomplish exploits. Israel, through Tyre, had access to extensive trade networks. Tyre, through Israel, had access to the most powerful economy in the region. The two nations used each other’s strengths for simultaneous prosperity. In fact, even with its trade routes and scattered colonial possessions, it is unlikely a city-state like Tyre would have become as wealthy as it did if it had not been for the backing of the Israelite empire.

This history, however, comes with a vitally important lesson.

In the world of academia, the ancient kingdom of Israel is one of the most controversial civilizations to study. Why? Mainly because in order to study Israel you have to study the Bible. The Bible not only describes Israel in detail, it describes the Israelite kingdom as having tremendous wealth and power. While some scholars accept this, and the evidence that supports this claim, others say the Bible’s description of Israel as a rich, powerful, sophisticated civilization is untrue or greatly exaggerated.

Meanwhile, few scholars today dispute the history of ancient Tyre. In general, the history of this city—including its rise, golden age and fall—is accepted among scholars. This is despite the fact that the Phoenicians themselves left few written records—far fewer than the Israelites left. Incredibly, the Bible is widely accepted as one of the main historical sources for Phoenicia.

According to The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, there is a “dearth of direct and informative sources on Phoenician society in general.” The Oxford Handbook states that the “glimpses [the Bible provides on Phoenicia] prove to be valuable in light of the general scarcity—especially in earlier periods—of information on the Phoenicians.” In a 2004 essay published by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Bible is listed first among the sources that “much of our knowledge about the Phoenicians … is dependent on.”

Isn’t this remarkable—and terribly hypocritical? The Bible can be used to inform our understanding of ancient Phoenicia, but it can’t be used to inform our understanding of ancient Israel.

But it’s not just the Bible. Homer identified the Phoenicians’ trade in luxury goods as occurring at roughly the same era King David was importing luxury goods from Phoenicia. Archaeology confirms the barbaric practices of Baal worship, promoted both in Phoenicia and Israel. Nebuchadnezzar’s conquest is verified by both the Bible and his own records.

And putting the Bible together with archaeology and secular texts shows that Israel had a great deal of influence in Phoenician civilization. Phoenicia owes its existence to the fact that Israel spared it from conquest. Tyre associating with the strong, prosperous empires of David and Solomon would have undoubtedly contributed to it becoming an economic powerhouse. Solomon’s Phoenician-engineered temple would have been the pinnacle of artisanship from a culture already renowned for fine craftsmanship. And there is even evidence that the Phoenician language and alphabet were influenced by the Israelites (“The Origins of the Alphabet,” page 19).

Yet in so many scholarly narratives, this Israelite connection is completely overlooked. If Phoenicia’s history can be verified with the Bible, why can’t Israel’s? If Tyre was a strong, prosperous monarchy in the Iron Age, why wouldn’t Israel be also?

This is arguably the most important aspect of the Phoenicians’ legacy: Their history proves the veracity of the Bible. In a sense, then, they left their Israelite allies one gift that has lasted for millenniums: a testimony to the accuracy of their Scriptures. And we still benefit from that testimony today.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians