The Persians—a name that conjures up thoughts of high-quality rugs. Besides craftsmanship in carpetry, however, the Persians were once the leaders of the largest empire in the world. They were a proud and noble people whose greatest leader uniquely built a legacy of peace with the Jewish people. That Persian legacy holds great lessons for us today, especially in relation to modern-day peace efforts in the Middle East. Let’s dig into the fascinating record of Persian history, as told through archaeology and the Bible.

Genesis of an Empire

It is well known that the Iranians of today are the descendants of ancient Persia. Indeed, to call an Iranian an “Arab” would be rather offensive. Yet links between the Arab and Iranian worlds run deep, in particular with adherence to Islam. Many Arabs, particularly Saudi Arabians, are descendants of Abraham’s son Ishmael. While God did not intend to bestow the same riches and dynasty on Ishmael that He did through Isaac, He did promise that Ishmael would be blessed, and that from him would come 12 princes (Genesis 17:20—fulfilled in Genesis 25:12-16). Mohammed, founder of the Muslim faith, was born in the Ishmaelite land of Saudi Arabia. It is interesting to note that in following Mohammed, Iran’s official religion is Islam, and specifically Twelver Shiism—the belief in the religious succession of 12 chief imams, leaders or “princes.” Perhaps this idea stemmed from the ancient Arabic significance of 12 princes, rooted in the earliest days of Mohammed’s ancestors, the Ishmaelites. According to Twelver Shiism, the reign of the 12th imam was cut short—Twelvers believe that his return from “hiding” will be preempted by cataclysmic world events, hence the radical Iranian elites’ desire to perpetrate chaos.

The Persians, as a people, do not feature in the biblical record until quite late—the earliest written references are found in Ezekiel, written around the start of the sixth century b.c.e. First, we will briefly cover their earliest history.

Beginning in the middle of the third millennium b.c.e., the territory of Iran was occupied by a powerful people known as Elamites. Their chief city, Elam, is linked back to their forefather of the same name (Genesis 10:22). The Elamites became powerfully established in the southern region of Iran throughout the ensuing centuries, yet were gradually whittled away by the might of the neighboring Assyrian Empire. (Led by King Ashurbanipal, the Assyrians finally crushed Elam during the middle of the seventh century b.c.e.) Around 1000 b.c.e. (the time of David’s reign in Israel), a nomadic Indo-European people called “Parsa” migrated into the territory of modern-day Iran—adjacent to the then-Elamite territory. These people would become known as the “Persians,” ancestors of the Iranians. The first time that “Parsa” is mentioned in archaeological context is in the ninth-century annals of Assyrian King Shalmaneser ii.

Two particular groups emerged from these immigrations—the Medes and Persians. Evidence shows that initially (at least according to the Assyrians), the Medes were the more extensive and important group—and probably exerted some kind of control over the Persians. The Medes grew in such power that by the end of the seventh century b.c.e., they were able to challenge the Assyrian Empire. The granddaughter of Median leader Cyaxares married the famous Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, and this Medo-Babylonian alliance compounded problems for Assyria. In 612 b.c.e., the Assyrian capital Nineveh was sacked by the Medes and Babylonians.

After the Assyrian territory was divided up, a new balance of power was reached between Media, Babylonia, Lydia and Egypt. The Persians, however, living among the Medes, were about to rise up and change that. A ruling Persian dynasty had been established in Fars (southwest Iran). A Persian leader named Cyrus ii (who would become known as Cyrus the Great) began reigning over his people in 559 b.c.e. (after the Babylonians sacked Jerusalem, c. 586 b.c.e.). Cyrus married the daughter of Median King Astyages, united several Persian and general Iranian groups under his banner, and began diplomatic relations with the Babylonians. This worried Median King Astyages—and rightly so. Cyrus fought and defeated Astyages, with many of Astyages’ own Median troops deserting to the Persian side under the brilliant leadership of Cyrus. Thus, beginning 550 b.c.e., the Median Empire became the Persian Empire. Cyrus subsequently crushed the Lydians, before setting his sights on the Babylonians.

A Prophesied Leader?

We are now in the time period that the Bible describes the Persians. As stated above, the earliest chronological mention of the Persian people is in the book of Ezekiel (27:10 and 38:5)—probably written shortly after 600 b.c.e. There is, however, an earlier, incredible prophecy of the man who would become Persia’s leader, Cyrus the Great.

Cyrus lived circa 590–529 b.c.e. Yet the Prophet Isaiah mentioned him, by name, 150 years earlier!

Here is what Isaiah recorded (Isaiah 44:28; 45:1-3; King James Version):

[God] saith of Cyrus, He is my shepherd, and shall perform all my pleasure: even saying to Jerusalem, Thou shalt be built; and to the temple, Thy foundation shall be laid. Thus saith the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I have holden, to subdue nations before him; and I will loose the loins of kings, to open before him the two leaved gates; and the gates shall not be shut; I will go before thee, and make the crooked places straight: I will break in pieces the gates of brass, and cut in sunder the bars of iron … that thou mayest know that I, the Lord, which call thee by thy name, am the God of Israel.

This is an amazing prophecy that a leader named Cyrus would come on the scene. He would “subdue nations.” And he would issue a command that Jerusalem and the temple would be rebuilt. All this, prophesied 150 years before he was even born!

Of course, many say that these passages of Isaiah were written after Cyrus the Great came on the scene. In fact, people have been so skeptical of Isaiah that they date his completed works as late as 70 b.c.e.! Yet the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls showed a copy of Isaiah dating to 200 b.c.e. And while no earlier copies of Isaiah have yet been discovered, the historian Josephus wrote that Cyrus actually read and marveled at Isaiah’s prophecies concerning himself! (See Antiquities of the Jews, xi, i.)

Let’s examine how Cyrus fulfilled these detailed prophecies.

Conquering Babylon

Isaiah 45:1-2 specifically prophesy Cyrus’s conquest of Babylon. The “two leaved gates,” “gates of brass” and “bars of iron” refer to the Babylonian defenses. Ancient Babylon was one of the most remarkable cities ever to have been constructed—especially considering it was built without the use of modern machinery. Herodotus recorded that the walls of the city were over 90 meters (300 feet) high and nearly 30 meters (90 feet) wide. Chariots could be driven atop the city walls. These walls were lined with massive bronze gates (the gates translated as being made of “brass” in Isaiah can also mean “bronze”). Watchtowers 130 meters (420 feet) high towered above the landscape. The mighty Euphrates River flowed into and through the sprawling, almost 200-square-mile city.

Babylon, during this time, was ruled by Nabonidus; his son Belshazzar had control over Babylon city proper (especially while Nabonidus was away on foreign assignments). Belshazzar had chosen to dive into a certain fateful night of drunkenness and excess (Daniel 5:1-4). The ruler used ransacked vessels from Jerusalem’s temple for his debauched feast. Suddenly, a hand materialized in midair and began writing on the wall: “mene, mene, tekel upharsin” (verse 25). The Prophet Daniel, a prominent figure of Babylonian politics from the days of Nebuchadnezzar, was brought in to explain what the writing meant. Verses 26-28:

This is the interpretation of the thing: MENE, God hath numbered thy kingdom, and brought it to an end. TEKEL, Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting. PERES, thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians.’

Daniel then simply states, “In that night Belshazzar the Chaldean king was slain. And Darius the Mede received the kingdom …” (verses 30-31).

How Babylon Fell

This collapse of the capital city of Babylon occurred 539 b.c.e. According to ancient clay records, Babylon was captured without a fight. The book of Daniel confirms that the massive city came under Medo-Persian control in only one night. How could this happen?

As Brad Macdonald, Assistant Director of the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, wrote in an article titled “The Startling Truth About One of History’s Greatest Kings”:

[Cyrus’s] strategy was brilliantly simple. First, he dug trenches upstream and diverted water from the Euphrates [which coursed through Babylon’s walls] into a large reservoir. Once the water level had dropped, and under the cover of darkness, Persian soldiers slipped into the knee-deep water, marched up the riverbed, and snuck under Babylon’s giant gates.

Although the soldiers had infiltrated the outer gates, there were still brass and iron internal gates controlling access out of the riverbed and into the city. If they couldn’t get through the gates, the soggy riverbed would turn the Persians’ tactical advantage into a massive kill box. …

But strangely, on the night of the invasion, there were no soldiers, and the internal gates were wide open. … Having quenched the Euphrates and penetrated the outer gates, the Persian soldiers were able to stroll through the internal gates, taking the city—including the shocked king—by surprise!

It happened just as God prophesied in the book of Isaiah, at this point nearly 200 years earlier. God left “open before him the two leaved gates; and the gates shall not be shut … I will break in pieces the gates of brass, and cut in sunder the bars of iron” (Isaiah 45:1-2; kjv). This same prophecy states that God would “loose the loins of kings”—as the Jamieson, Fausset and Brown Commentary explains, this refers to a feeble, relaxed state, rather than the strong kingly image of being well prepared, having loins “girded.” This was exactly the state of Belshazzar, as Daniel describes, on the night that Babylon was taken!

Daniel states that after Babylon fell, it came under the rulership of Darius the Mede (Daniel 5:31). There has been much debate about who this figure was in history. It is obvious that this was during the time that Cyrus the Great ruled from Persia’s capital (Daniel 6:28). Darius would have been a lesser ruler entrusted with administering the city of Babylon.

Some of the notable candidates for Darius include the Median noble Cyaxares ii and Cyrus’s general Gubaru. Whoever Darius the Mede was, the Prophet Daniel certainly had favor with him, serving under him as his second-in-command.

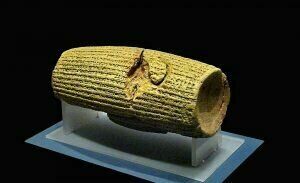

The Cyrus Cylinder

Cyrus was renowned for his benevolence toward conquered peoples. That was one of the reasons why his sprawling empire held together so well. Gone were the days of the sadistic Assyrian Empire, where terrified nation-states would seek to break away whenever they thought they had a fighting chance. Cyrus’s magnanimous kingship is best displayed by the most famous artifact from his time, the Cyrus Cylinder.

The Cyrus Cylinder is a smallish, cylindrical tube covered in Akkadian cuneiform script. It is a declaration by the Persian king to his new Babylonian subjects, allowing them freedom to continue living life as normal and serving their own gods. This was stunningly different from how conquering nations would normally treat their crushed enemies. Cyrus claimed, on the document, that the Babylonian god had chosen Cyrus to improve the lives of the Babylonians. The cylinder describes Cyrus’s efforts to resettle the displaced and to restore temples. Thanks to this decree, a great deal of freedom was allowed to the Babylonian people.

The reason this document is such an exciting piece of archaeology is due to its biblical parallels. While the Cyrus Cylinder was sent to the Babylonians, the Bible records that a parallel document was likewise sent to the Jews (remember that they had been taken captive by the Babylonians about 60 years earlier). This is what the Bible records that Cyrus wrote to them (Ezra 1:2-3):

‘Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia: All the kingdoms of the earth hath the Lord, the God of heaven, given me; and He hath charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whosoever there is among you of all His people—his God be with him—let him go up to Jerusalem, which is in Judah, and build the house of the Lord, the God of Israel, He is the God who is in Jerusalem.

Just as Cyrus worked to restore the Babylonian temples, he did the same for the Jewish people. As a result, they were free to return to their homeland and rebuild the temple and city walls of Jerusalem, as told in the accounts of Ezra and Nehemiah.

Queen Esther

The account of Esther occurred sometime after the initial Jewish return to Israel to build the temple, yet before Nehemiah arrived to rebuild Jerusalem’s fortifications. As with Darius, there is much debate as to the Persian king who married the Jewess Esther. Xerxes i is the widely accepted candidate, ruling from 486-465 b.c.e. Persian and Aramaic renderings of the Greek “Xerxes” are very similar to the Hebrew rendering “Ahasuerus.”

As the story goes, King Ahasuerus of Persia was entertaining friends, and his wife Vashti refused to come at his request to “show the peoples and the princes her beauty; for she was fair to look on” (Esther 1:11). To cut a long story short, Ahasuerus put Vashti away and had his servants seek a new wife. The young Hebrew Esther, under the guardianship of her uncle Mordecai, went to the king as one of the candidates, and was ultimately selected to become his wife. During her tenure as queen, she was used by God to stop a plot by the evil Haman to kill all of the Jews in the Persian Empire. The celebration of Haman’s foiled genocide is embodied today in the Jewish holiday of Purim.

The names “Esther” and “Mordecai” seem to be of pagan origin. The original names of Daniel and his three friends had been changed to pagan Babylonian ones (Daniel 1:7). And we know that Esther’s original name was Hadassah (Esther 2:7). “Esther” is similar to the name of the Babylonian goddess “Ishtar,” and “Mordecai” appears to hearken to the god Marduk. During the reign of Xerxes i, archaeology has provided evidence of a royal courtier known as “Marduka.” This could have been the very same Mordecai, whom the Bible says also served in some manner in the king’s palace (verses 5, 11) and “sat in the king’s gate” (verse 19).

Nehemiah’s Wall

After Queen Esther’s reign alongside (probably) Xerxes i, we arrive at the time period of Nehemiah (middle of the fifth century b.c.e.). Nehemiah was a “cup-bearer” to the well-known Persian king Artaxerxes i. Upon hearing of the dilapidated state of Jerusalem, Nehemiah gains royal assent to travel to Israel and rebuild the city, including the famous “Nehemiah’s wall” constructed in only 52 days (Nehemiah 6:15). This wall has remarkably been discovered by excavators in Jerusalem!—one of the archaeologists, our aiba Office Manager Brent Nagtegaal, had a part in its discovery.

Dated by a rich assemblage of Persian pottery, this wall (and an associated tower) exhibited a “rushed” nature of building—as should be expected, considering the wall was built so quickly. The wall was commissioned 445 b.c.e.—and the remains that have been uncovered abut the monumental construction in Jerusalem known as the Stepped Stone Structure. This likely places this part of Nehemiah’s wall with the sections constructed by Shallum and (a different) Nehemiah, as told in Nehemiah 3:15-16.

Persian Downfall

The Persian Empire would last, after the time of Nehemiah, for about a century longer. And just as its rise under Cyrus the Great was accurately prophesied in advance, so too was its downfall.

During the time of the Babylonian Empire, the prophet Daniel had prophesied that the succession of world empires would go from King Nebuchadnezzar, represented by a statue’s golden head, to the following empire represented by the silver chest and arms of the same statue (Daniel 2:31-45). These two arms represented the Medes and the Persians. Daniel further prophesied, before even the Babylonian Empire ended, that the following Persian Empire would be like a bear with three ribs in its mouth (representing the conquered Babylon, Lydia and Egypt; Daniel 7:1-5). Yet this Persian Empire was then prophesied to fall to an emerging empire with the swiftness of a leopard (verse 6). This leopard (described with four wings and four heads) is, of course, Alexander the Great’s Greek Empire (and the four quarters of that empire split between Alexander’s generals after his death—see Daniel 11:1-4).

Alexander the Great is widely known for the blinding pace at which his empire grew. The Persian Empire fought several battles against the Greco-Macedonian troops, suffering a critical defeat at Issus at the hands of Alexander the Great’s armies in 333 b.c.e. The Persian King Darius iii fled the battle, leaving his children, wife and mother to be captured by Alexander. In 331 b.c.e., Darius was defeated again at Gaugamela, and though he again escaped, the empire belonged to Alexander. Darius was ultimately killed in his final escape by a Bactrian satrap.

Persia Today

Thus the Persian Empire of ancient times ended. Two groups of Persians living within the modern territory of Iran would rise up successively to become empires throughout their post-Greek history—firstly, the Parthian Empire (247 b.c.e.–c.e. 224), and then the Sasanian (or Sassanid) Empire (c.e. 224–651). Similar to King Cyrus, the Sasanians were (at times) friendly toward the Jewish people, and even fought alongside them in order to recapture Jerusalem from the Christians. However, once Jerusalem was recaptured, the Persians betrayed the Jews and banished them from the city. A Jewish gold hoard dating to this period (including a large menorah medallion and many gold coins) was found in 2013, just south of the Temple Mount. Jerusalem’s Jews of this period, who expected (as under Cyrus) to rebuild a third temple under Persian control, were forced to hide their treasures and flee for their lives.

From the following centuries that heralded the rise of Islam, the Persian inhabitants of Iran were sucked into the growing Muslim world, taking on Twelver Shiism. And from the time of the Sasanians, the Persian land became known as “Eran,” meaning “Aryan” or “land of the Aryans.” Today, of course, we call it Iran.

In 1979, the Western-allied Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown during the Islamic Revolution. The Islamic Republic of Iran has since been ruled by the Ayatollahs, who have made Israel and the U.S., in particular, their enemies. The current oppressive regime represent a black stain in the chronicle of Iran, and a sharp diversion away from the territory’s greatest, most widely-respected history.

But just before that revolution occurred, there was a glimmer of light.

In 1971, the Shah Pahlavi put on the world’s “most expensive party,” celebrating the 2,500-year anniversary of the founding of the Imperial State of Iran and Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great. The shah invited leaders from all over the world to attend. The party was 10 years in planning, and lasted five days. Six hundred foreign dignitaries attended, staying in an extravagant tent city established outside the ancient capital city Persepolis. Two hundred and fifty custom-built red Mercedes carried visiting diplomats across the desert. Festivities began at the tomb of Cyrus, and the Cyrus Cylinder was featured at the event, honoring this rich Persian heritage that so significantly shaped world history.

A number of ornate French Baccarat crystal candelabra were commissioned for the event, each consisting of over 800 pieces and weighing 300 kilograms (650 pounds). Two of these regal candelabra—or, to use the Hebrew term, menorahs—are today owned and kept at the headquarters location of the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology in Edmond, Oklahoma. They are a literal beacon of light in honor of Iran’s greatest ruler—and what made him so.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians