It was supposed to be a simple salvage operation to repair a crumbling Hasmonean tower. But after Dr. Eilat Mazar and her team started excavating, they soon realized that this project would be far more. By the time they were done, they had made a sensational discovery.

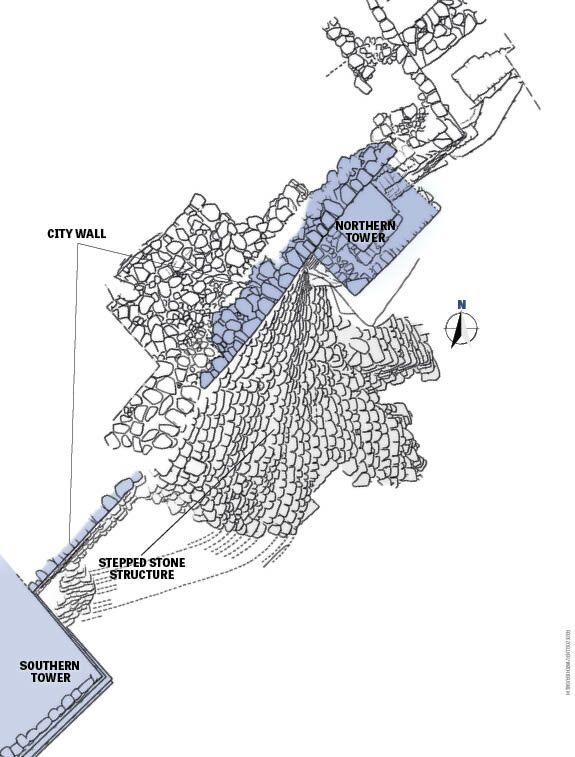

Situated in the City of David, at the upper northern end of the Stepped Stone Structure, the Northern Tower was a poorly constructed fortified structure. It had the remains of a mikveh (ritual purification bath) on top. The Northern Tower was largely unearthed in the 1920s. Until 2007, archaeologists, including Dr. Mazar, generally assumed the tower dated to the Hasmonean period (second century b.c.e.).

By 2007, the Northern Tower was in a perilous condition, at risk of collapse. The structure had clearly been built quickly in antiquity, with its stones loosely cobbled together. Most significantly, nearly a century of nearby archaeological digs had compromised its structural integrity. Without immediate intervention, the tower would collapse. Early that year, the Israel Antiquities Authority (iaa) attempted to carry out restoration work, yet the soundness of the tower continued to deteriorate. Thus, the iaa approved Dr. Mazar to lead a salvage excavation to repair the tower.

The repair process was theoretically simple: Mazar and her team would dismantle the tower, carefully numbering each rock and noting its place in the wall. Then, using modern mortar, they would rebuild it. However, with an edifice this ancient, things are rarely simple. What transpired was an unexpected, intensive six-week excavation that ended in a radical re-dating of the Northern Tower—and the revival of some extraordinary biblical history.

Persian Fingerprints

Dr. Mazar’s dismantling of the Northern Tower began in a straightforward manner. However, as the team got close to the bottom, it became clear that the foundation wasn’t sufficiently stable to support the tower’s reconstruction. After consulting with authorities and colleagues, Dr. Mazar began to excavate the strata under the tower to find a firm layer on which to rebuild. The material uncovered in this strata enabled a secure dating of the Northern Tower—and everyone was in for a surprise.

During the excavation it also became clear that the Northern Tower had been built at the same time as a straight section of wall atop the Stepped Stone Structure and that the tower and this section of wall were part of the same edifice.

Among the artifacts uncovered directly beneath the Northern Tower was a surprising discovery: two buried dogs. Studying the “epiphyseal closure” of the bones, as well as age-related wear, scientists determined that the dogs had died of old age. Comparing the finds with other excavations across Israel, Mazar noted that dog burials of this kind are characteristic of a specific historic setting: the Persian period. (The largest dog burial was found in Ashkelon; thousands of dogs were buried here, with a peak number during the Persian period. It appears that the Persian faith held dogs to have a holy status, and linked them to health and medicine.)

A large amount of pottery fragments were discovered under the dogs. These sherds dated unequivocally to the Persian period and supported the dating of the dogs to the late sixth and early fifth century b.c.e.

Finally, the absence of certain material helped Dr. Mazar date the tower and associated wall. Yehud seal impressions are very common during Persian period Judah. Yehud was what Judah was called during Persian rule. During Yigal Shiloh’s excavations in the City of David in the 1980s, many Yehud bullae had been found, all of which dated to the second half of the fifth century b.c.e. or later. But here, in this almost five-foot-thick Persian layer beneath the Northern Tower, Dr. Mazar didn’t find a single one. That meant this material must have been in place before the middle of the fifth century b.c.e.

Using pottery typology and the dog burials, Dr. Mazar concluded that the Northern Tower and wall were constructed around 450 b.c.e.

The Biblical Record

Though the discovery of the Persian wall and tower was unexpected, when considering the historical sources, it is entirely unsurprising. The Bible discusses just such a wall, at length and in great detail.

The biblical account of “Nehemiah’s wall” is well known. Nehemiah was a Jew in Persian captivity. He was the cupbearer to the Persian King Artaxerxes. In 444 b.c.e., Nehemiah was granted permission to return to Judah and rebuild the dilapidated walls and gates of Jerusalem, which had been destroyed during the Babylonian invasions in the early sixth century.

The book of Nehemiah shows that Judah at the time was surrounded by enemies and under constant threat of attack. Nehemiah and his crew worked with great urgency and astonishing speed. Nehemiah 6:15 says the wall was built in just “fifty and two days.”

Studying Nehemiah’s account, Dr. Mazar noted that the construction of the Northern Tower and associated wall, which she had scientifically dated to circa 450 b.c.e., matched precisely with the biblical account. Not only did the dates match, so did the quality of construction. The tower and wall were not masterpieces of engineering. Their construction quality showed that they had been built hastily—just as Nehemiah recorded.

Nehemiah 3 describes the wall’s construction in detail. It specifies various lengths of walls, towers and gates being rebuilt, along with names of the workmen. Comparing the section of wall Dr. Mazar discovered with the biblical description, one can even speculate as to the specific person who built it: Nehemiah, son of Azbuk (verses 15-16; this is a different Nehemiah from the book’s main figure).

There is another interesting titbit regarding the wall. In Nehemiah 4:35, Tobiah the Ammonite, one of Nehemiah’s adversaries, mocks the builders. He tells them, “Even that which they build, if a fox go up, he shall break down their stone wall.” In other words, Even a fox could knock your wall down! Perhaps it is some poetic justice that directly underneath the excavated section of Nehemiah’s wall were the crushed carcasses of two very dead canines?

Incidentally, the Bible records that Nehemiah had three primary enemies: Sanballat the Horonite, Tobiah the Ammonite, and Geshem the Arabian. Two of these figures—Sanballat and Geshem—have been identified through archaeological excavation. Tobiah has not, but archaeology has proved his name common for this period.

The biblical account of these figures also helps relate the reason for a lack of Yehud seal impressions. Yehud seals are characteristic of Persian control and administration over Judah. Yet during the initial decades of Persian rule, the empire didn’t have a strong administration established across all its dominions. Under the umbrella of the Persian Empire, the Holy Land was loosely controlled by sparring factions, including Horonites, Ashdodites, Ammonites and Arabs (Nehemiah 2 and 4). Over time, the Persian Empire became more consolidated in regional administration (most notably under Darius i) and began to exert more direct influence over local affairs. This helps explain the emergence of Yehud seals only in the later periods.

Related Discoveries

Beneath the five-foot layer of early Persian period material, Dr. Mazar discovered a Babylonian layer. This clearly related to the earlier Babylonian period, circa 586 to 539 b.c.e. A number of significant finds appeared in this stratum.

Among them was a shiny black stone seal bearing the biblical Hebrew name Shelomith. The image above the name is decidedly Babylonian. It features two worshipers, an altar and the moon symbol of the Babylonian god Sin. Mazar postulates that the seal was made in Babylon and the Hebrew name incised later. She also references 1 Chronicles 3:19, which mentions a Shelomith, daughter of Zerubbabel, who was on the scene immediately after this Babylonian period.

Directly under the Babylonian stratum was the thick destruction layer corresponding to the fall of Jerusalem. This layer contained several small finds, including many bronze and iron arrowheads. This layer included the bulla of the biblical prince Gedaliah, son of Pashur.

The preserved section of Nehemiah’s wall uncovered by Dr. Mazar tapers out at the summit of the Stepped Stone Structure. Continuing south along the same line, however, a related section of wall appears (see map). Though no stratified material was present to be able to date this southern continuation of the wall, Dr. Mazar believes that, based on its relationship to the northern wall and tower, it too dates to the Persian period and is another part of Nehemiah’s wall.

This southern continuation of wall abuts the Southern Tower. Like the Northern Tower, this large tower was originally assumed to have been Hasmonean. Unfortunately, excavations during the 1920s removed the earth layers abutting the tower. It appears that unless the tower itself is excavated, it cannot be dated properly. Again though, given the nature of the tower and how it relates to the wall extending south of the Stepped Stone Structure, Dr. Mazar believes it too must be part of Nehemiah’s wall. The fact that the Southern Tower was built on top of houses destroyed by the Babylonians (circa 586 b.c.e.) and therefore dates to sometime after the sixth-century b.c.e. destruction further proves that it was part of Nehemiah’s wall.

The most logical conclusion is that all three edifices—Southern Tower, Northern Tower and the wall connecting them over the Stepped Stone Structure—are part of Nehemiah’s wall.

One final note: Nehemiah 3:16 says the tombs of the kings of Judah are situated alongside a massive stepped structure, at the end of the section of wall built by Nehemiah, son of Azbuk. These tombs have not yet been found—but surely they must be close to the portion of Nehemiah’s wall recently discovered. Will the tombs of the kings soon be discovered, as an end-time prophecy in Jeremiah 8:1-2 indicates?

Enter the Critics

Before Dr. Mazar’s salvage excavation, no finds existed relating to Nehemiah’s reconstruction of Jerusalem’s wall. Bible skeptics pointed to the book of Nehemiah and its detailed description of the wall and asked why none of its remains had ever been discovered. Since 2007, they can no longer ask this question. But the skeptics have not retired.

Archaeologist and Bible minimalist Prof. Israel Finkelstein dismisses the discovery, arguing that because we only have foundational material dating to the Persian period, the structure itself could have been constructed at any later period. “The wall could have been built, theoretically, in the Ottoman period [circa 1300-1900 c.e.],” he stated.

This argument is spurious. Remember, the tower was capped with a Hasmonean mikveh, which means the structure was completed no later than the first century b.c.e.—the end of the Hasmonean period.

Consider too: If the structure had been built this late, more than 300 years after the Persian period, why were there no later Hasmonean remains under the tower? After all, a wealth of Hasmonean remains were scattered throughout surrounding earth strata.

Clearly the tower must have been built at the same time period as the foundational early Persian material, sealing it from intrusion of later pottery shards—including material (such as Yehud seals) from the late Persian period. According to Prof. Richard Rigsby: “Finkelstein is overstating his case. The language he’s using is more the language of debate than that of scholarship.”

Others have criticized Dr. Mazar for using the Bible. These critics say Mazar cannot be trusted because she has a Bible bias. The fact is, prior to this excavation, Mazar—like many others—believed the Northern Tower was Hasmonean. She was not looking for this discovery, nor searching for evidence proving the Bible true. When the science pointed to this discovery being Nehemiah’s wall, she was as surprised as everyone else.

Dr. Mazar did not rush to conclude she had discovered Nehemiah’s wall. Rather, she diligently and responsibly followed the science, and objectively compared it to the biblical record. After thoroughly documenting the evidence, Mazar summarized her discovery of Nehemiah’s wall in the scientific report documenting the excavation, The Summit of the City of David Excavations 2005–2008, Final Reports Volume i. On pages 201-202 she wrote:

“In summary, the remains discovered … well substantiate the biblical account. … Taking into account the strong archaeological evidence on the one hand and the detailed biblical account on the other, we propose identifying the Northern Tower, and likely the Southern Tower as well, together with the segment of the city wall (W27), as all forming part of Nehemiah’s fortifications.”

Doesn’t this conclusion make sense? You don’t have to be a devout believer in the Bible to see what Dr. Mazar discovered actually matches up with the biblical account.

Watching the debate over the excavation of the Northern Tower, it’s hard not to see parallels with events described in the book of Nehemiah. Anciently, Nehemiah and his helpers faced such stout resistance they required military protection. “They which builded on the wall, and they that bare burdens, with those that laded, every one with one of his hands wrought in the work, and with the other hand held a weapon” (Nehemiah 4:17; kjv). Dr. Mazar also faces tough opposition, albeit more academic. There is no shortage of modern-day Sanballats and Tobiahs.

One year before she discovered the wall, Dr. Mazar, like a modern Nehemiah, described her approach to archaeology: “I work with the Bible in one hand and the tools of excavation in the other, and I try to consider everything.” Perhaps it is fitting that her excavation and identification of the wall took about as long as it did for Nehemiah to build it.

Despite opposition, as Dr. Mazar has said before, in the end, the stones speak for themselves. Nehemiah couldn’t have said it any better himself.