They were a powerful, warring nation that exerted an iron-like grip over their expansive and powerful empire. They were known for cruel and unusual torture and mass slaughter of their enemies. And yet strangely enough, they were uniquely renowned for an incident of national repentance of their actions.

They were the Assyrians.

Genesis of an Empire

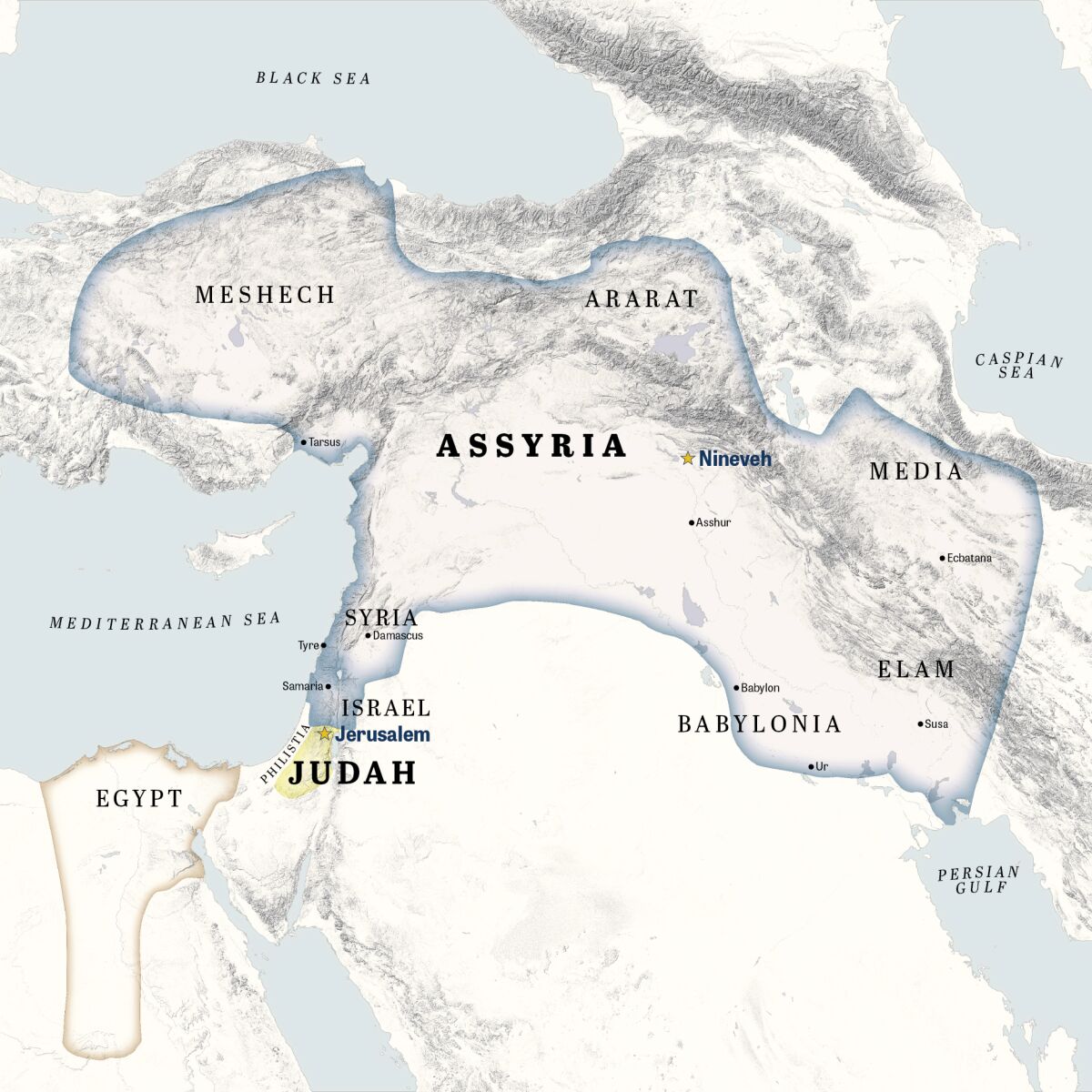

The Assyrians trace their origins back to one of their founding cities, Assur. The ruins of Assur are located near the Tigris River, in the northern part of what is modern-day Iraq. The start of this ancient city-site has been set at roughly 2500 b.c.e. The Bible chronology shows the Flood occurred around this time—and one of the “founding fathers” following the Flood was Asshur, son of Shem (Genesis 10:22). Asshur evidently worked in conjunction with Nimrod in establishing this city named after himself (verse 11). Thus the legacy of Assur began, alongside other ancient and verified contemporary cities like Elam (Asshur’s brother of the same name) and Kish (note Asshur’s cousin Cush). Genesis 10:11 also records the establishment of the cities Nineveh and Calah. Nineveh became Assyria’s greatest city. The city Calah, also called Kahlu, is better-known by its more common name, Nimrud.

The Assyrians are not mentioned in detail in the biblical record until nearly 2,000 years after the establishment of Assur (mid-eighth century b.c.e.). This article will focus largely on the later period of Assyrian history and its parallels with the Bible, so we’ll only briefly cover the intervening time.

According to historian Simon Anglim:

The Assyrians created the world’s first great army and the world’s first great empire. This was held together by two factors: their superior abilities in siege warfare and their reliance on sheer, unadulterated terror.

The Assyrian Kings Lists give us a long chronological overview of the rulers of Assyria. Three of these lists have been found in three of Assyria’s chief cities: Assur, Nineveh and Dur-Sarukkin. The lists are largely consistent and point to one original document from which they were sourced. The earliest Assyrian rulers were recorded as “kings who lived in tents,” and start with King Tudiya (c. 2350 b.c.e.). The second listed ruler, Adamu, is of particular note—his name reveals the remarkably early use of the name Adam.

Early on, Assyria rose as a strong kingdom and empire. The patriarch Abraham fought against and conquered an alliance of four belligerent “kings” during the 19th century b.c.e. (Genesis 14:1). The historian Josephus reveals that these four rulers were actually part of the wider early Assyrian Empire (Antiquities, i, ix, 1). Yet their early dominance was smashed at the hands of Abraham and his men.

Throughout most of the second millennium b.c.e., Assyria was a dependency of Babylonia (first known as Babel, this was the chief city of the ancient leader Nimrod: Genesis 10:10 and chapter 11), and then subsequently the Mitanni Kingdom. In the 14th century b.c.e., Assyria became an independent power, exerting a strong influence over swathes of Mesopotamia, Armenia and Syria. However, it was from the ninth century b.c.e. onward that the Assyrian Empire expanded to truly great heights of power and influence. Thus it is at this time that the Assyrians begin to emerge from the pages of the biblical text as a real threat to Israel’s existence.

Strangely enough, this time period of the Assyrian Empire is first brought up in the Bible in the context of repentance. This is related through the record of Jonah.

Assyrian Cruelty

The Prophet Jonah was on the scene during the reign of Jeroboam ii (2 Kings 14:25). As the well-known story goes, Jonah was commanded by God, “Arise, and go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness is come up before me” (Jonah 1:2). This message would have been delivered probably around the first part of the eighth century b.c.e.

We must go further back to understand what kind of “wickedness” was going on in Assyria.

Cruelty is perhaps the word most synonymous with Assyria, particularly during this period. Ancient inscriptions, annals and carvings bring this vividly across. Ashurnasirpal ii (reigned 883–859 b.c.e.) was known for hanging his enemies on posts, flaying them, and lining city walls with their skins. He also burned or beheaded his enemies—if they were fortunate—because those still alive would have noses, ears, eyes, arms or other extremities removed.

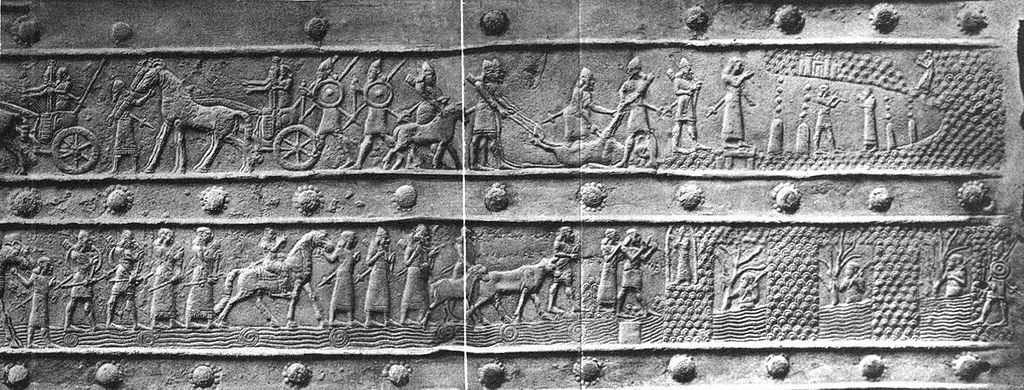

His son Shalmaneser iii (reigned 858-824 b.c.e.) continued in his footsteps. The famous Balawat Gates from his reign depict Assyrian soldiers hacking apart the captured enemy, dismembering hands and feet. Heads were hung from walls, and impaled captives were lined up on display. Pillars of human heads were stacked like totem poles.

Many other Assyrian reliefs and records also illustrate Assyria’s barbarism. On one clay prism, Assyrian King Esarhaddon records how he paraded conquered nobles through the streets “wearing” the heads of fellow nobles on their shoulders. Another records a defeated Arabian leader being taken to Nineveh and made to live in a kennel alongside the dogs guarding the city gates. On the Taylor Prism, King Sennacherib brags about creating so much blood from death and disembowelment that his horses waded through it like a river. The prophet Nahum condemns the Assyrian bloodlust and cruelty (Nahum 3:1, 19).

This was the kind of terror faced by dissenters of the Assyrian Empire up to the time of Jonah. Thus it is no wonder that Jonah was fearful of carrying God’s warning to the Assyrians at Nineveh—and no wonder why God threatened divine destruction of the city.

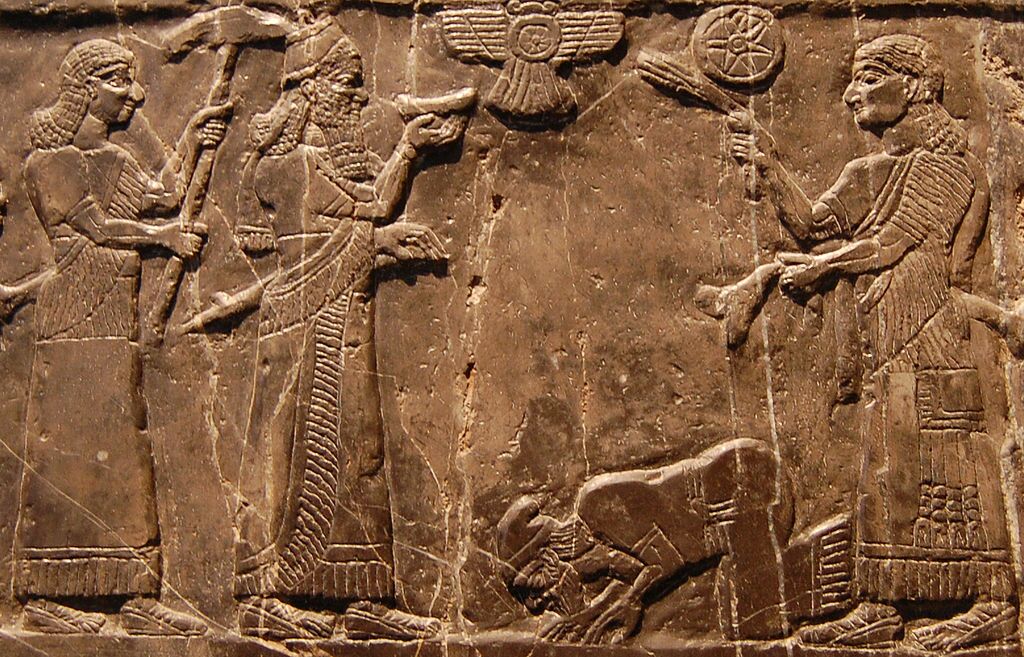

Note: Dating to Shalmaneser iii’s reign of terror, a Black Obelisk was discovered, displaying images of tribute being brought before the Assyrian king. One notable section of the Obelisk displays an image of an Israelite king and contingent bowing and bringing tribute. The associated inscription reads: “The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears.” This extremely important biblical artifact proves the existence of Israelite kings Jehu and Omri, and helps shed light on Jehu’s situation as described in 2 Kings 10:31-36. Jehu was under continual attack by Hazael, king of Syria. He must have attempted to seek help from the Assyrian king in countering his attackers.

Jonah’s Journey

As the book of Jonah describes, the prophet fled by ship bound for Tarshish—completely the opposite direction from Nineveh. To quell a fierce storm, Jonah was tossed overboard and swallowed up by “a great fish.” After three days and nights (and after Jonah had repented for running away), the fish returned him to dry land, and Jonah began his journey to Nineveh.

The Bible describes Nineveh as a massive city of “three days journey” in size (Jonah 3:3). Remarkably, archaeology shows that Nineveh plus her suburbs was about 60 miles across—equating to 20 miles of walking per day, or a three days’ journey. Further, excavations reveal that the city proper of Nineveh was an area of at least 1,730 acres—allowing plenty of room for the 120,000 residents (Jonah 4:11). Approaching Nineveh, Jonah would have been dwarfed by walls 30 meters tall and 15 meters thick (according to the historian Xenophon).

Jonah began warning the inhabitants of God’s impending judgment. Remarkably, “the people of Nineveh believed God, and proclaimed a fast … word came unto the king of Nineveh, and he arose from his throne, and he laid his robe from him, and covered him with sackcloth, and sat in ashes” (Jonah 3:5-6). The king proclaimed a fast even for all animals. This Asiatic practice of even causing the animals to mourn is not without precedent, as Herodotus recorded. Nineveh’s king admitted for what sins God’s punishment was coming: “[L]et them turn every one … from the violence that is in their hands” (verse 8). He continued: “Who can tell if God will turn and repent, and turn away from His fierce anger, that we perish not?” Verse 10 continues:

And God saw their works, that they turned from their evil way; and God repented of the evil, that He had said that He would do unto them; and He did it not.

There is some debate as to when this event happened, and under which leader. The debate also includes whether this was a lesser ruler only of Nineveh, or the king of all Assyria (since Nineveh was the capital at the time). What is known is that these were dark days for the Assyrian Empire, and expansionism toward the Mediterranean coast ground to a halt for many decades.

Israelite Oppression and Downfall

Our next biblical view of the Assyrians is not long after the account of Jonah—perhaps within several decades. And it is in the context of oppression.

2 Kings 15:19 reads:

And Pul the king of Assyria came against the land: and Menahem [king of Israel] gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, that his hand might be with him to confirm the land.

King Pul was likely not of royal lineage, but probably took over the throne of Assyria in a coup. Upon assuming the throne, he took on the title Tiglath-Pileser iii—his birth name was Pulu, or Pul (a name he used concurrently as king, as the Phoenician Incirli inscription shows). Tiglath-Pileser took the Assyrian Empire to new heights of dominance. He also established himself as king over Assyria’s archrival, Babylon. This newly invigorated Assyria had a catastrophic effect on Israel.

Menahem was king over the northern kingdom of Israel, reigning from Samaria. During his rebellious reign, Israel came under heavy tribute to the Assyrians. This tribute is listed in the Calah Annals of Tiglath-Pileser iii. King Menahem is also mentioned in a stele of Tiglath-Pileser as “Menachem of Samaria.”

After the death of Menahem, his son Pekahiah took over the throne. After only two years, however, he was killed by the captain Pekah, who then began to rule over Israel. During the reign of Pekah, Tiglath-Pileser iii swept into Israel and took many cities, carrying away the inhabitants (verse 29). This was the beginning of the end for Israel (mid-to-late-eighth century b.c.e.). There are various archaeologically confirmed references to Pekah—perhaps the best is Tiglath-Pileser iii’s inscription referring to the “House of Omri” and “Pekah,” after whom “I installed Hoshea over them.” As the Bible confirms in verse 30, Hoshea conspired against Pekah and overthrew him.

Around this time Ahaz, king of Judah, was having problems with a Syrian invasion. He requested help from Tiglath-Pileser iii, paying him a great deal of treasure stripped from the temple (2 Kings 16:6-9). Tribute from Ahaz is also found listed in the ancient Assyrian records of Tiglath-Pileser iii (where Ahaz is known by the longer title “Jehoahaz of Judah”). Ahaz’s attempt at cooperation with the king of Assyria proved to be more trouble for Judah, however. “Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria came to him, but he gave him trouble instead of help” (2 Chronicles 28:20; New International Version).

Tiglath-Pileser iii’s successor, Shalmaneser v, led the Assyrian forces in the final destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel (721–718 b.c.e., 2 Kings 17:1-6). Shalmaneser died before the siege ended, and it was under his successor, Sargon ii (Isaiah 20:1), that Israel was ultimately conquered and carried away captive. “So was Israel carried away out of their own land to Assyria unto this day” (2 Kings 17:23). From this point on, the northern 10 tribes would become the “lost 10 tribes” of Israel (read here to discover where they actually went). In place of the evicted Israelites, the Assyrian king planted people that would become known as “Samaritans” (verses 24-29), a troublesome group mentioned in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, as well as in the New Testament.

Judahite Oppression

Hot on the heels of Assyria’s overwhelming victory against the northern kingdom, Sargon ii’s successor, Sennacherib, decided to sweep into and conquer the southern kingdom of Judah (2 Kings 18:13). Sennacherib was incredibly successful—except in his campaign against Jerusalem.

Sennacherib’s plunders into the Judahite kingdom are well documented in archaeology, particularly his attack against Lachish. You can read a thorough account of this attack here.

2 Kings 18:13-14, 17 read:

Now in the fourteenth year of king Hezekiah did Sennacherib king of Assyria come up against all the fenced cities of Judah, and took them. And Hezekiah king of Judah sent to the king of Assyria to Lachish [the city had been already overthrown, and his forces were now based there], saying, I have offended … and the king of Assyria sent Tartan and Rabsaris and Rabshakeh from Lachish to king Hezekiah with a great host against Jerusalem ….

Archaeologists have discovered massive carved portrayals (known as “reliefs”) of this siege against Lachish in Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh. The long, detailed depictions show masses of Assyrian soldiers attacking, defeating and then leading away captive the Jews from this city. The portrayal also shows the city gate being besieged, and massive siege towers being pushed up a ramp in order to attack the city. These depictions match exactly what has been revealed at Tel Lachish. A massive siege ramp has been identified at the site that these Assyrians would have used in order to launch their assault on the city from atop the towers. Much weaponry was also found, evidencing the terrifying battle fought at Lachish.

The conquest of Lachish is one of Sennacherib’s most documented accomplishments. The reliefs discovered in Nineveh provide a glimpse into the Assyrians’ abhorrent cruelty.

One scene shows Judean prisoners being stripped naked, handcuffed and then impaled on large stakes. Another shows a soldier forcing a leader to kneel while another prepares to cut him down. One scene shows Judean leaders being made to parade barefoot and bareheaded (a symbol of subservience) in front of King Sennacherib before being beheaded. Another relief depicts two naked Judeans being flayed alive while a column of exiles looks on. These prisoners are bound flat, arms stretched wide, while the soldiers grip their legs to complete their grisly task. It was common for the Assyrians to boast of using their enemies’ heads and skins as decorations for their city walls.

From the new Assyrian base at Lachish, Sennacherib attempted to conquer Jerusalem. King Hezekiah initially delivered tribute to assuage the Assyrians (verses 14-16), but it did not stop their intent to conquer the city. After a desperate prayer to God for safety, Hezekiah was informed by the Prophet Isaiah that the Assyrians would not so much as shoot an arrow against Jerusalem. The Assyrians (185,000 of them) were wiped out overnight by an angel (2 Kings 19:34-36).

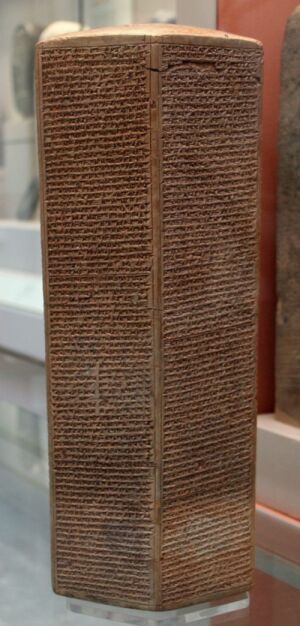

Interestingly, on an Assyrian artifact known as Sennacherib’s Prism, the king boasts: “As for Hezekiah, I shut him up like a caged bird in his royal city of Jerusalem.” The text goes on to delineate the initial tribute he had received from Hezekiah. Yet it makes no mention of an attack on, let alone conquest of, Jerusalem. Just as the Bible says—he wasn’t allowed to! Of course, this wasn’t something the boastful king of Assyria would admit.

For those who would simply dismiss this account of Assyria’s complete destruction in Jerusalem at the hand of an angel, there are some ancient secular records confirming this. According to the third-century b.c.e. Babylonian historian Berossus:

Now when Sennacherib was returning from his Egyptian war to Jerusalem, he found his army under Rabshakeh his general in danger, for God had sent a pestilential distemper upon his army; and on the very first night of the siege, a hundred fourscore and five thousand, with their captains and generals, were destroyed.

So the king was in a great dread and in a terrible agony at this calamity; and being in great fear for his whole army, he fled with the rest of his forces to his own kingdom, and to his city Nineveh; and when he had abode there a little while, he was treacherously assaulted, and died by the hands of his elder sons, Adrammelech and Seraser, and was slain in his own temple, which was called Araske.

Herodotus was a fifth-century b.c.e. Greek historian. Many scholars believe that his account of Sennacherib’s defeat in a battle with Egypt at the city of Pelusium is in fact a reference to the sudden death of the Assyrian army during the siege of Jerusalem. Herodotus wrote that the Egyptian leader Sethos prayed to his god for help in defeating the massive Assyrian army. He wrote:

As the two armies lay here opposite one another, there came in the night, a multitude of field mice, which devoured all the quivers and bowstrings of the enemy, and ate the thongs by which they managed their shields. Next morning they commenced their fight, and great multitudes fell, as they had no arms with which to defend themselves. There stands to this day in the temple of Vulcan, a stone statue of Sethos, with a mouse in his hand, and an inscription to this effect—‘Look on me, and learn to reverence the gods.’

The Assyrian threat at that time was also the reason for the digging of Hezekiah’s tunnel beneath Jerusalem. This discovered tunnel is an impressive, 530-meter-long conduit carved straight through bedrock, referenced in several scriptures.

The Downfall of Assyria

Under Sennacherib, the Assyrian Empire began to fragment and suffer multiple wars. The territory of Babylonia, having been subdued and included as a part of Assyria during Tiglath-Pileser iii’s reign, began to fall apart thanks to insurrection by the Chaldeans and Arameans. In 681 b.c.e. (according to standard chronology), Sennacherib was murdered by two of his sons, Adrammelech and Sharezer (Isaiah 37:37-38)—this is corroborated by various ancient records, implicating Arda-Mulissi for the murder (Adrammelech), who would have been assisted by his brother Nabu-sarru-usur (Sharezer). A third son, Esarhaddon, reigned in his place.

Esarhaddon is known for his defeat of Egypt in 671 b.c.e., subsequently carrying the title “king of Egypt.” He is the last king of Assyria to be mentioned by name in the Bible. The Assyrian Empire was finally smashed c. 612–609 b.c.e., defeated by the Chaldeans and Medes. The Chaldeans subsequently established their own independent Babylon.

Assyria Today

It is hard to believe that the citizens of one of the world’s greatest and most enduring empires should fade almost completely from worldview. Over the course of nearly 2,000 years (up until around 600 b.c.e.), the Assyrians had been one of the largest and most significant forces shaping the ancient world. What happened to them?

A small, crushed minority survive to this day, living stateless in their Mesopotamian homeland. Those still living in modern-day Iraq number around 1 million.

But the history of man is the history of migration. We cannot expect the entire Assyrian people to have remained in the same territory—nor to have just been limited to the Mesopotamian region.

A medieval inscription in the west German city of Trier proudly declares that “Before Rome, Trier stood for 1,300 years.” The construction of Trier is said to have taken place under the direction of Trebeta, son of the ancient Assyrian King Ninus (Josef K. L. Bihl, In Deustchen Landen). According to the story, Trebeta had been driven out of Mesopotamia by his mother, Semiramis. He left with a “great multitude of Assyrians” and established the city of Trier in modern-day Germany. Thus we see textual reference to Assyria’s fingerprints into Europe and specifically Germany as early as 2,000 b.c.e.

Historical references show that after the Assyrians’ defeat around 600 b.c.e., populations labeled as “Assyrian” were found all around the Black Sea region (as noted by Sylax, Diodorus Siculus and Pliny the Elder). This follows along with a Bavarian tradition that their Germanic peoples came from the region of Armenia, near the Black Sea. The Scythians had in fact retreated to this location, after conquering the Assyrians. They evidently would have brought many Assyrian captives with them.

The historian Jerome wrote in the fourth century c.e. about Indo-Germanic tribes that during his time were invading into Europe. He stated of them: “Assur [the Assyrian] also is joined with them” (note Psalm 83:8)—the Assyrians during the fourth century were pushing into Europe!

Leonard Cottrell wrote in Anvil of Civilization (1957):

In all the annals of human conquest, it is difficult to find any people more dedicated to bloodshed and slaughter than the Assyrians. Their ferocity and cruelty have few parallels save in modern times.

It thus should not be surprising that those perpetrators of modern “bloodshed and slaughter” (penned just after World War ii) are themselves the descendants of the Assyrians. It is also fitting that the once-great city named after the Assyrian forefather—Assur—has been chiefly excavated by German archaeological teams—and that the center of research for the field of Assyriology has long been Germany.

“The Destruction of Sennacherib” | A Poem by Lord Byron (1815)

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea, When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.Like the leaves of the forest when Summer is green, That host with their banners at sunset were seen:

Like the leaves of the forest when Autumn hath blown, That host on the morrow lay withered and strown.For the Angel of Death spread his wings on the blast, And breathed in the face of the foe as he passed;

And the eyes of the sleepers waxed deadly and chill, And their hearts but once heaved, and for ever grew still!And there lay the steed with his nostril all wide, But through it there rolled not the breath of his pride;

And the foam of his gasping lay white on the turf, And cold as the spray of the rock-beating surf.And there lay the rider distorted and pale, With the dew on his brow, and the rust on his mail:

And the tents were all silent, the banners alone, The lances unlifted, the trumpet unblown.And the widows of Ashur are loud in their wail, And the idols are broke in the temple of Baal;

And the might of the Gentile, unsmote by the sword, Hath melted like snow in the glance of the Lord!

Experience ‘Seals of Isaiah and King Hezekiah Discovered’. Request the free brochure.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Assyrians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Babylonians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Canaanites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Egyptians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Hittites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Kushites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Moabites

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Persians

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Philistines

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Civilizations: The Phoenicians