Last December, headlines were made following the discovery of a large stone table at Beth Shemesh, dating to the 11th century b.c.e. This ritual stone appeared to closely parallel the biblical description of a “great stone” that the ark of the covenant was placed on at that same location and around the same time period.

I printed off a thorough description of the artifact, written up in Haaretz, and settled in to read. Almost immediately, I was struck by a rather jarring introduction of the discovery by the leader of the Beth Shemesh excavations, Tel Aviv University’s Dr. Zvi Lederman:

This would be a rare case in which we can merge the biblical narrative with an archaeological find.

A rare case of an archaeological discovery matching the biblical account? Given that I spend some time writing on this subject and helping supervise excavations, I thought it might be interesting to lay out the discoveries of last year alone—2019—as a case study on the rarity of biblical corroboration in archaeology. The following discoveries are ordered by month, as they were released to the press.

A recognized expert has made an unsubstantiated claim. Let’s put it to the test.

January

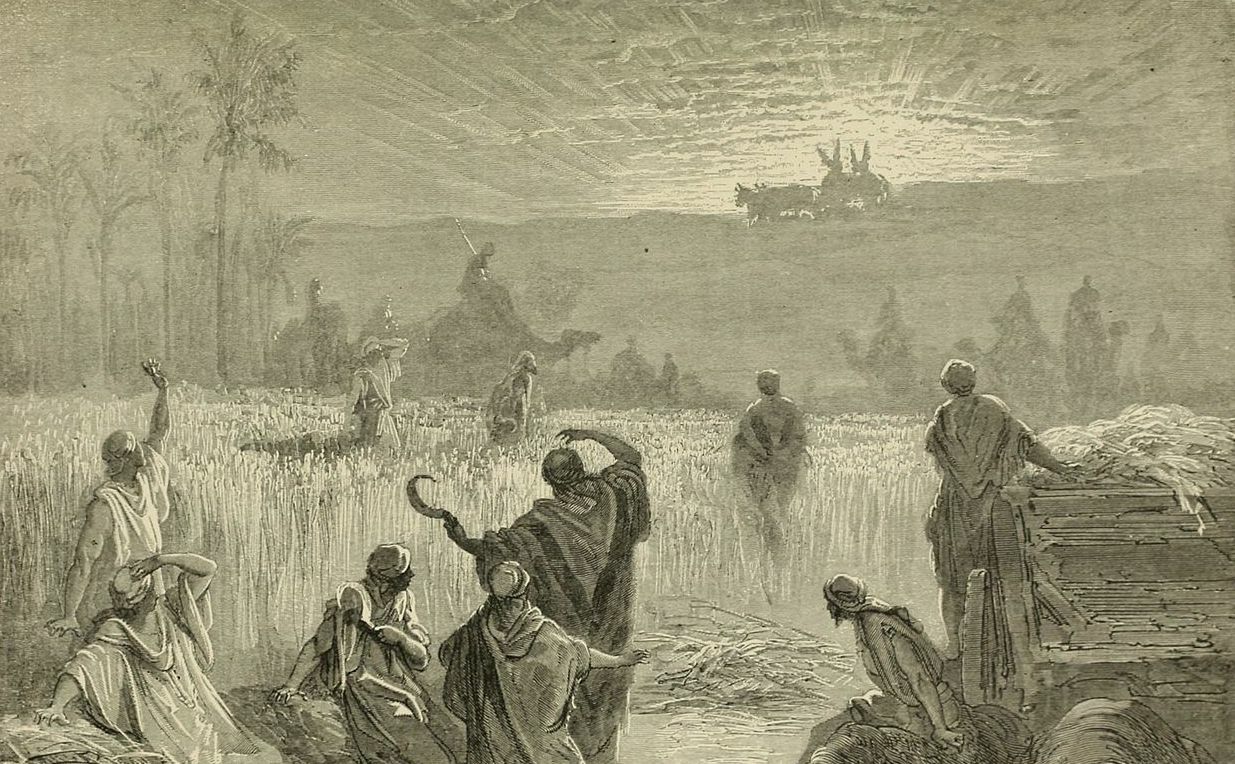

Kirjath Jearim—The year actually began, as it had ended, with an “ark of the covenant”-related discovery. Reports broke at the start of 2019 about the excavation of a massive, eighth-century b.c.e. raised platform at Kirjath Jearim. Kirjath Jearim is well known in the biblical account as the city that housed the ark of the covenant for two decades, before it was moved to Jerusalem (1 Samuel 7:1-2). Codirector of the excavations, Tel Aviv University professor Israel Finkelstein—a famous Bible critic, identified the peculiar 1.7-hectare platform as a “shrine” to the placement of the ark of the covenant. Finkelstein admittedly doesn’t believe in the ark, but nevertheless associates the supposed “memory” of it as the reason for construction, as relating to the biblical account.

February

March

Jerusalem—Excavators of the Givati Parking Lot unearthed two bullae belonging to the seventh century b.c.e., from what was once the capital’s royal acropolis. One bulla (seal impression) was of particular note, bearing the inscription “Belonging to Nathan-Melech, Servant of the King.” The name Nathan-Melech can be found in 2 Kings 23:11. He was a servant in King Josiah’s seventh-century royal court. Nathan-Melech occupied a chamber near the temple entrance, adjacent to a court in which the pagan Judahite kings had established a place of sun worship. The bulla matches the biblical figure in name, royal position, dating and findspot, thus serving to confirm his existence.

The second bulla contained the name “Ikar, son of Mataniah.” Mataniah is a common biblical name (used 16 times), and also belongs to a biblical individual in the royal court at this period. Whether or not this bulla refers to the biblical Mataniah is of course unclear, but the discovery at least corroborates the use of the name in the Bible.

April

May

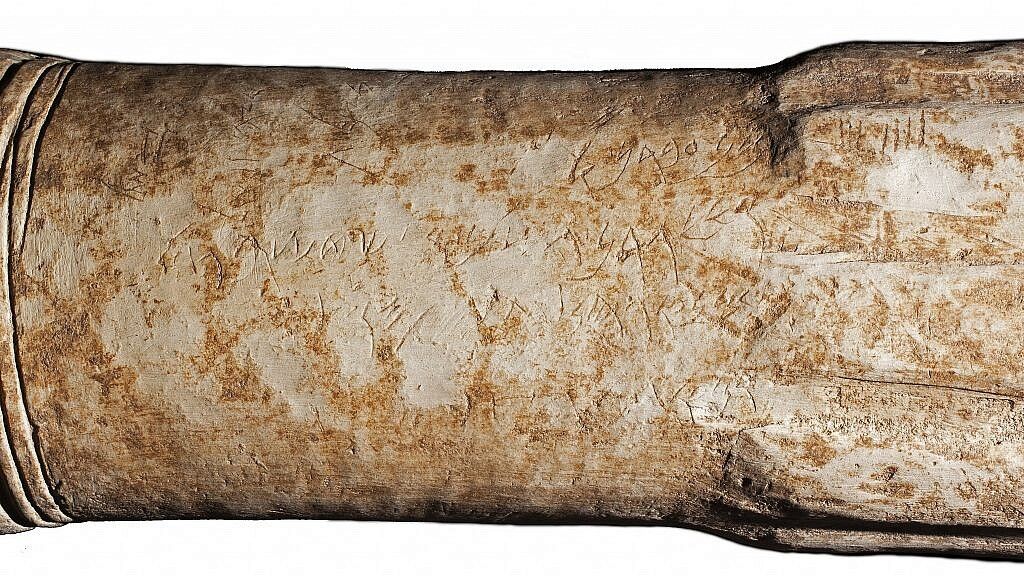

From the Lab—The Tel Dan Stele is famous as the first confirmed early inscription mentioning King David. The Mesha Stele is another such inscription—albeit the reference to the king was damaged and, therefore, uncertain. Finkelstein, together with Tel Aviv University professor Nadav Na’aman and French scholar Thomas Römer, completed a paper claiming that the preserved text did not read “House of David” after all, but instead perhaps the name “Balak”—as a centuries-old memory of the Exodus figure.

Immediately following their release, however, an academic response was given by Associate Prof. Michael Langlois, who has spent years poring over the Mesha Stele. By way of new, high-tech 3D digital imaging of the artifact, Langlois—who had been about to release his own detailed study—dismissed the above theory and confirmed that “House of David” was indeed the best reading. (Further—the lengthy Mesha Stele inscription closely parallels the account of 2 Kings 3. See our article here for more information.)

June

Ataruz—A Moabite stone altar bearing two inscriptions, discovered at the site of biblical Ataroth, was deciphered and released to the public in June. The ninth-century b.c.e. artifact made headlines as possibly containing the earliest reference to the term “Hebrews” (the inscriptions are, however, fragmentary). Besides the possible Hebrews association, the artifact pairs up alongside the Mesha Stele in corroborating the biblical account of 2 Kings 3—helping to confirm a ninth-century Moabite rebellion, war against the Israelites, the occupation of Ataroth, and worship at an Israelite “high place.”

Southern Israel (location undisclosed)—A brigade of Israel Defense Forces (idf) paratroopers on an archaeology outreach discovered a 2,700-year-old watchtower. The dating puts the use of the tower, by their ancient idf contemporaries, during the reign of King Hezekiah (a king whose rule—as described in the Bible—has almost entirely been corroborated by archaeology). It is theorized that the tower served as a fire-beacon post, of the type referenced in Jeremiah 6:1 and Judges 20. The geographical position of the watchtower shows that it was an early-warning system against the Philistines—the Bible, as well as Sennacherib’s inscriptions, relate Hezekiah’s military and political successes against the Philistines (2 Kings 18:8).

July

Tel Shikmona—July was a big month. It was revealed that Tel Shikmona—a site whose purpose has puzzled researchers for decades—was in fact a facility for mass-producing purple-dyed textiles. Purple dye is mentioned numerous times throughout the Bible, particularly in relation to the tabernacle and temple. The coastal town of Shikmona is the first-discovered Iron Age evidence for the production of such dye from Israel and even from neighboring Phoenicia, the place for which it was famous. The dye was produced by harvesting and crushing murex sea snails, which were abundant just off the coast.

Ashkelon—Scientists and historians have long speculated about where the Philistines came from. The Bible states that they were from the land of Caphtor (Jeremiah 47:4; Amos 9:7), identified as the island of Crete. Following the excavation at Ashkelon of the first-ever discovered Philistine cemetery, a formal dna analysis was performed. The samples taken from the Philistine bodies, dating to circa 13th century b.c.e. (the time of a significant Philistine migration), showed that they were most closely matched to a south European population and, specifically—surprise, surprise, to the inhabitants of the island of Crete.

Tel et-Tell—Excavators have identified this site as likely being the biblical city of Bethsaida mentioned numerous times in the New Testament as a significant Roman period city and place of the miracle of the “loaves and fishes.” Excavators here also discovered one of the largest gatehouses of northern Israel in use during the reign of King David. At this time, it is believed to have been the capital city of the Geshurite tribe. David is recorded as having raided Geshur and later married the daughter of the Geshurite king, leading to speculation that such a marital “transaction” may have been arranged—as was so often the case—within this city gatehouse. Other discoveries at the site point to the biblical account—including Shishak’s 10th-century conquests, as well as Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser’s invasion during the eighth century b.c.e.

Khirbet a-Ra’i—Archaeologists excavating this town on the border of ancient Philistia and Israel declared that they had found the elusive biblical city of Ziklag. Ziklag was originally a Philistine city, unusual in that it was handed over to David and his men as a gift while they were on the run from the Israelite King Saul. Khirbet a-Ra’i shows evidence of Philistine settlement from the 12th to 11th centuries b.c.e.—but by the start of the 10th century b.c.e., the pottery remains change to those of a Judahite settlement, with no sign of conflict or destruction. Evidently, the city changed hands in a peaceful manner, to Israelite control—the artifacts precisely paralleling those of another “Davidic” site, Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Further, during the period of Judahite occupation, evidence shows the city witnessed a fiery conflagration. This, too, fits the biblical narrative. While David and his men were out on an expedition, the Amalekites entered Ziklag and “burned it with fire” (1 Samuel 30:1), taking the women and children captive. David and his men quickly routed the invaders and reclaimed their families and possessions.

Tel Hazor—The Bible describes Hazor as the “head” of the Canaanite cities, prior to the Israelite conquest of the Promised Land (Joshua 11:10). And archaeological excavations have certainly backed that up, revealing the largest biblical-era site in all Israel (the population is estimated at 20,000). This year, excavators revealed a large, 3,500-year-old staircase attesting to the grandeur of this city just prior to the Israelite invasion. The full extent of the staircase—unparalleled in its tight-fitting construction style—has not yet been uncovered. Further evidence of Israelite Hazor was discovered at the site this year, attesting to the site’s final moments before the destruction by the Assyrians, as described in 2 Kings 15:29.

Tel es-Safi—This Philistine site is better known as the infamous Gath, biblical hometown of Goliath. And that specific “hometown”—11th-century b.c.e. Gath—has just been unearthed this year. While a slightly later, 10th-century b.c.e. city was known to excavators, the fortress corresponding to the story of Goliath (and again, the ark of the covenant’s Philistine “tour”) had remained elusive—until now. Eleventh-century b.c.e. Gath has proved to be a city fit for giants. The city was evidently more colossal than any other thus far discovered in the Levant dating to this period, with walls over four meters thick and built of stones up to 2 meters in size. The strength of the city attests to the biblical account of the powerful dominance the Philistines exerted over Israel at this time (1 Samuel 10-13).

August

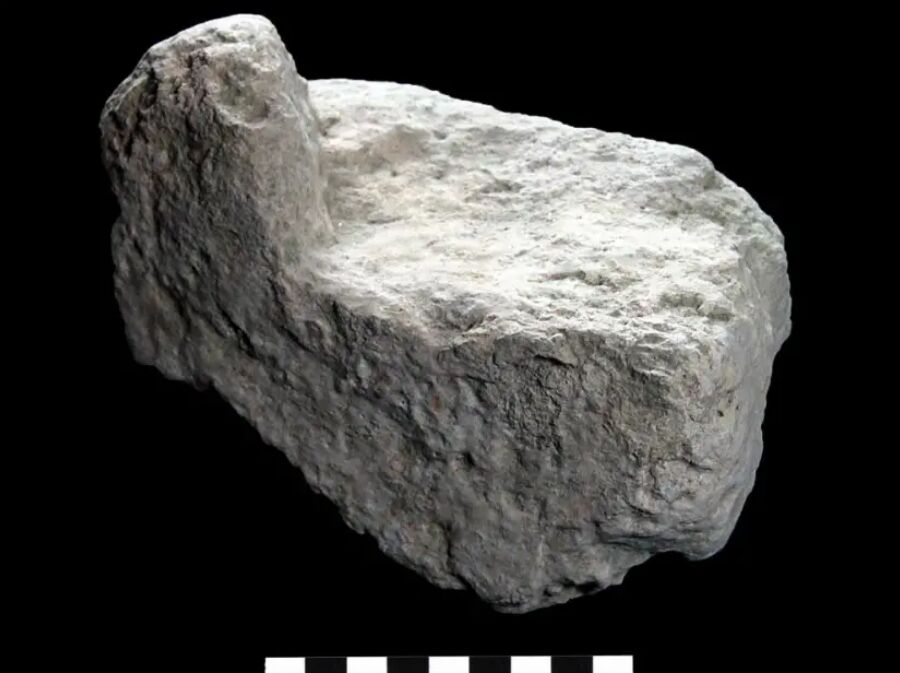

Tel Shiloh—Three “altar horns” were discovered at Shiloh during the summer excavations. These horns, placed at the four corners of an altar, are characteristically Israelite and a commanded altar feature (e.g. Exodus 27:2), and are referenced throughout the Hebrew Bible. Shiloh is famous as the site of the biblical tabernacle. While the stone altar horns were all discovered outside of their original context, they were all discovered in the vicinity of a monumental Iron Age i building, orientated east-west (a direction of potential religious significance). Further, they were discovered in the same area as a ritually significant ivory pomegranate (pomegranates are mentioned in the Bible in connection with the temple and tabernacle). As such, it is believed that the altar horns relate to altar use during the Iron Age i period of the tabernacle.

Jerusalem—Excavators on the hill of Mount Zion found a large sixth-century b.c.e. ash layer full of arrowheads and smashed Iron Age pottery attesting to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem circa 586 b.c.e. A rare, precious jewelry item was found within the significant Iron Age structure, leading the excavators to suspect that this building belonged to a wealthy individual—and that it was (for this and other reasons) perhaps one of the “great men’s houses” that Nebuchadnezzar burned with fire (2 Kings 25:9).

September

Jerusalem—Excavations adjacent to the Temple Mount revealed another bulla, this one bearing the inscription “Belonging to Adonijah, the Royal Steward.” Again, though this bulla does not relate to a biblical figure, the name Adonijah is given to three biblical individuals (most famously, a son of David), and thus the discovery corroborates the biblical use of the name. Likewise, the title royal steward (literally, “Over the House”)—the “highest-ranking ministerial position beneath the king”—is found often throughout the Bible.

Aravah Valley—Based on excavations at two ancient copper mining sites in the Aravah Valley (Timna and Faynan), researchers concluded that the kingdom of Edom was formed much earlier than originally thought by scholars—instead, aligning with the biblical account. Contrary to the prevailing scholarly theory, the Bible states that the Edomite kingdom was formed before Israel’s (which began with Saul during the 11th century b.c.e.—Genesis 36:31). This has now been proved chiefly through analysis of slag deposits at the mines, showing evidence of regional Edomite control following an Egyptian-dominated period, and prior to a Hebrew takeover at the start of the Israelite monarchy. Of the discovery, Haaretz’s Ariel David commented that this biblical corroboration was “unexpected.” In a similar thread to the comment on the Beth Shemesh ark discovery, he wrote: “It’s not every day that science and archaeology find confirmation of the Bible.” Certainly not—but it’s close.

Excavations of the mining sites have revealed evidence of the Israelite takeover of the mines (2 Samuel 8:13-14); peak output of copper and transport of material to Jerusalem, relating to the mass use of copper in the temple (1 Kings 7); and a takeover by Pharaoh Shishak at the end of the 10th century b.c.e. (2 Chronicles 12; also the Karnak Relief).

Tel Hadid—Excavations at this northern site yielded two 2,700-year-old tablets. This location was at the center of ancient Israel—however, the language of the tablets was not Hebrew, and the names listed were not Israelite. Instead, the discovery attested to the fact that the northern kingdom at this time—following the conquest and deportation of the Israelites by the Assyrians—was inhabited by foreigners. 2 Kings 17 describes the Assyrian deportation of Israelites and their replacement with a new group of Mesopotamians—a population that became known as Samaritans.

October

Jerusalem—Archaeologists have been aware for some years of a large (now underground) Roman street that served as a thoroughfare up to the Temple Mount. But it was only this year that the completion of the street was able to be dated, based on coin analysis, to the reign of Pontius Pilate, the infamous Roman governor known in the New Testament for his interrogation of Jesus Christ prior to the crucifixion. Until 1961, no artifacts had been discovered relating to this Roman governor. In the decades since, however, his existence has been well established through several discoveries, and now also his deeds while in power—here, in the construction of a grand Jerusalem avenue.

November

From the Lab—This one is a little different—a genetic study indicated (much to the astonishment of the Rockefeller and Basel University researchers) that some 90 percent of all animal species, as well as humans, descended from single ancestors that all began reproducing at roughly the same time, in relatively “recent” history. The geneticists speculated this as the result of a catastrophic disaster. The findings bring to mind the biblical Genesis account, both of creation as well as the story of Noah’s Flood—an event in which only select representatives of each species of land animal, including humans, were spared on the ark.

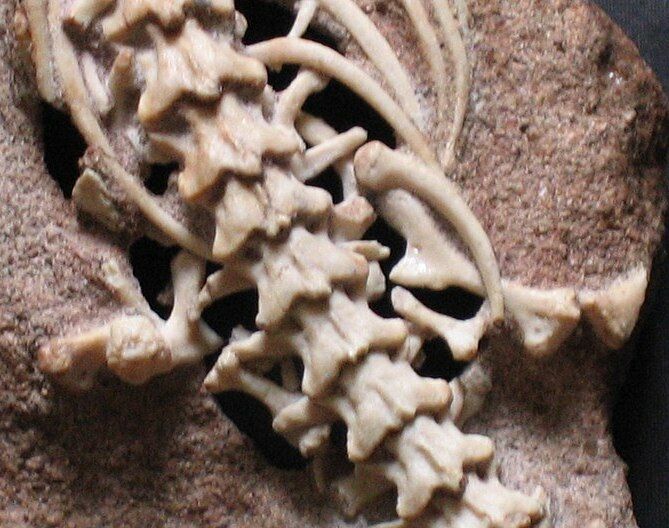

Patagonia—This one takes us a little further afield, to South America. Scientists have known about ancient legged serpents for some years—but the finds are generally poorly preserved. This year, a remarkably preserved cache of two-legged snakes was discovered, species Najash (named after the biblical Hebrew word for serpent). The discovery disproved one of the main evolutionary theories about snake development, and further attests to the Genesis 3 account of snakes “losing their legs” (see our article on legged serpents here).

December

Beth Shemesh—And we come full circle. Excavators at Beth Shemesh uncovered a massive ritual stone table in a room of worship, dating to circa 3100 b.c.e. The peculiar table hearkens to an account in 1 Samuel 6, where the ark of the covenant was delivered to Beth Shemesh around this same period, and was placed “on the great stone” (verse 15). Codirector Zvi Lederman explained that this was a “rare case in which we can merge the biblical narrative with an archaeological find.” Reporting on the discovery, Haaretz journalist Ariel David wrote: “If their hypothesis is correct [about this stone being linked to the ark of the covenant], the find would be evidence that the Bible contains kernels of historical truths from much earlier periods than most experts previously thought.”

A “rare case”? A surprising “kernel” of historical truth in the Bible?

Language like this is typical from institutions such as Tel Aviv University (a school that prides itself on biblical minimalism) and Haaretz. Unfortunately, it is all-too-easy for agenda-driven professionals to simply be taken at their sweeping generalizations, without any substantiation. Of course, blind and uneducated “faith,” drawing hasty biblical conclusions, can be a problem on the other side. Both extremes are pseudo-scientific “religions” in their own right—and oftentimes avowed Bible minimalists are the greater offenders, ignoring facts in favor of pet theories.

We have listed 20 of the more dramatic discoveries of 2019. The reader can make up his own mind as to the biblical significance. More examples could be provided. And by the way, 2019 was by no means an unusual year for biblical archaeology (I would rank 2018 as more significant).

Maybe this individual’s definition of “rare” is something different. I don’t know—but based on the discoveries of this year alone, the archaeological corroboration of the Scriptures doesn’t seem overly “rare” to me. You can decide that for yourself.