A 3,000-plus-year history in the Holy Land is often cited by Jews as one of their strongest claims to living in the land of Israel. The biblical history speaks clearly of the Israelites’ promised homeland in Canaan. It plainly describes the Israelites’ conquest of the Promised Land and establishment of a country of their own, with a capital eventually established in Jerusalem. It is a history celebrated and touted by many Israelis.

But to opponents of Israel’s right to exist, this establishment of the nation is considered quite differently. This history is considered quite differently. In some cases, more along the lines of a genocidal massacre. According to Richard Dawkins, “The Bible story of Joshua’s destruction of Jericho, and the invasion of the Promised Land in general, is morally indistinguishable from Hitler’s invasion of Poland, or Saddam Hussein’s massacres of the Kurds and the Marsh Arabs.”

It is fashionable today to speak in sweeping generalizations about the immoral brutality of Israel’s conquest of Canaan and establishment of its nation. But was that really how it happened? Or does this opinion belie little more than willful ignorance, or even willing deception? Let’s look at what really happened during the early days of the Israelite nation and the interactions of the Hebrews with the Canaanites. Let’s look at what the Bible—supported by archaeology—really says.

To do that, it’s best that we start not at the invasion itself, but 500 years before.

Land Grab? Or Land Purchase?

Canaan, at the time of the patriarchs, was sparsely populated. It was quite common for nomadic peoples to move freely through the land, farming and camping. Well before the Exodus, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, with their multitudes of families, workers and servants, already owned and operated vast swathes of land within Canaan. A significant portion of Canaan was already called “the land of the Hebrews” (Genesis 40:15). God promised that Abraham’s descendants would retain that land upon which he dwelt and that they would come to eventually possess all of the land of Canaan.

The first recorded biblical purchase of land was made by Abraham. He purchased a cave in Hebron within which to bury his dead wife, Sarah. The owner of the cave, Ephron, honored the “mighty prince” Abraham, actually pleading with him to take the cave and entire adjoining field free of charge. Abraham insisted on paying. Another example is of Jacob buying a swathe of land in Shalem (Genesis 33). Even David, as king ruling from Jerusalem many hundreds of years later, purchased land within Jerusalem from a Canaanite inhabitant. More on this later.

The idea that the Israelites entered a land that they had no prior claim to nor connection with is false. Much of Canaan was already known as the “land of the Hebrews” before the sojourn into Egypt.

Why does it matter, though, one might ask, if all the Israelites left Canaan to go into Egypt?

Israelites in Egypt and Israelites in Canaan?

It might come as a surprise to know that during the Israelites’ sojourn in Egypt—before the Exodus—there was an Israelite presence still established within Canaan. This is shown in 1 Chronicles 7.

Joseph’s son Ephraim had a number of sons who were living and working in Canaan. These men were later killed by the inhabitants of Gath, located in the southwest corner of the region of Canaan. Verse 21 shows that these Ephraimites were killed for attempting to steal cattle—perhaps wrongfully trying to take advantage of the riches of the Promised Land far too early and without just cause. As a result, these sons received no protection from God. There was no difference between stealing from a Gentile or from an Israelite, and they paid with their lives.

After this event, the mourning patriarch Ephraim had a daughter, who in turn bore a daughter of her own (Ephraim’s granddaughter). This Israelite granddaughter actually grew up to establish entire cities within Canaan (verse 24). This would have been during the time when the main part of the Israelites was in Egypt. These cities, which continued to function during the sojourn in Egypt, were rightfully included in the general tribal allotment given to Ephraim, after the bulk of the Israelites arrived at the end of the Exodus (Joshua 16).

The fascinating snippet about the descendants of Ephraim is only what the Bible briefly mentions regarding a part of one tribe of Israelites still in Canaan during the Egyptian sojourn. What about what it doesn’t mention? There could have been several other descendants of Jacob living throughout Canaan. (There is evidence to strongly suggest that many of Dan’s descendants emigrated to the Greek islands, and had much back-and-forth between Greece and the Promised Land.) Again, however, the main part of the Israelites did move to Egypt.

So the Israelite forefathers owned vast amounts of territory within Canaan. It was already becoming known as the “land of the Hebrews.” Due to a severe famine, most of the Israelites moved into Egypt, with the intent of only staying there temporarily. (Of course, “plans” changed once a dictatorial despot came into power.) Added to that, many, if not all, of the Canaanites also gave over their land to the Egyptians in exchange for food during the famine (Genesis 47). The land sales actually were made to the patriarch Joseph as a representative of the pharaoh (verse 20). And Joseph actually shows anticipation for the return of the Israelites to the Promised Land, commanding that they take his bones with them when they depart. Even during this sojourn in Egypt, Israelites continued to live and operate cities within Canaan.

So what of the invasion itself then? What of the brutal savagery?

Israelites Not Supposed to Fight (Originally)

Perhaps it will come as another surprise to know that the Israelites weren’t originally supposed to fight. God actually brought the Israelites through the wilderness the long way around—entering the Promised Land from the east side of the Jordan River—just so the Israelites would avoid encountering the Philistines and thus avoid the prospect of brutal warfare, which could have caused them to desire to return to Egypt. God actually did not want the Israelites to fight for the Promised Land. This is shown in Exodus 23:27-28:

I will send My terror before thee, and will discomfit all the people to whom thou shalt come, and I will make all thine enemies turn their backs unto thee. And I will send the hornet before thee, which shall drive out the Hivite, the Canaanite, and the Hittite, from before thee.

Further, in Exodus 34:11:

Observe thou that which I am commanding thee this day; behold, I am driving out before thee the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Hittite, and the Perizzite, and the Hivite, and the Jebusite.

This passage makes it very clear that God intended to miraculously clear the Promised Land for the Israelites. Originally, He did not desire the Israelites to take up arms and fight their way through the Promised Land. God intended to use hornets to drive away the inhabitants, implying that some of them would be given the chance to live—by being driven away and relocating elsewhere.

Not only that, God intended that He would drive the Canaanites out gradually to prevent the entire land of Canaan from being suddenly empty and thus becoming desolate and overrun with wild animals. Exodus 23: 29-30 states:

I will not drive them out from before thee in one year, lest the land become desolate, and the beasts of the field multiply against thee. By little and little I will drive them out from before thee, until thou be increased, and inherit the land.

Obviously, this original plan changed somewhat. Due to the Israelites’ sins, their lack of faith, and constantly taking matters into their own hands in the wilderness, God allowed them to face the consequences of their own paths and engage in warfare. Of course, the same purpose of clearing Canaan was to be reached, only through the sword instead. The general fate of the Canaanites remained the same. It was the Israelites that faced the added punishment of having to partake in warfare. (God did, however, still provide additional help in sending hornets—Joshua 24:12.)

And thus began a bloodlust campaign into Canaan. Or was it?

Aggression vs. Allegiance

Typically, when looking at the invasion of the Promised Land, critics are too focused on the supposed “atrocities” of the Israelites to see the forest for the trees. Let’s get the basic facts. Israel, under the leadership of Joshua, conquered a total of 31 kings.

Compare this to just one of the Canaanite rulers—Adonibezek. This man had conquered a total of 70 other kings in his lifetime—hardly a peaceable saint. In Adonibezek’s “mercy,” though, he refrained from killing the kings themselves—instead, he chopped off their thumbs and big toes and turned them into beggars “under his table” (Judges 1:4-7; King James Version).

Or what about the Ammonite King Nahash? This is going a little forward in time, but the principle still stands—Nahash proposed a peace deal with the Israelites of Jabesh-Gilead rather than simply slaughtering them. They would be allowed to live and become his servants, with one caveat—every inhabitant would have his or her right eye gouged out.

Yes, there certainly were wrongs committed by the Israelites. Some of the deeds committed by the tribe of Dan are a case in point (see Judges 18). These kinds of acts were condemned in the Bible. They are the exception, not the rule. And mutilation—a common, ancient regional practice—was in practice anathema to the Israelites.

Let’s look at more specifics of Israel’s conquest of the Promised Land. In certain cases, Israel simply requested peaceable passage through other nations on their journey into the Promised Land. In fact, Israel did not originally intend to acquire the large swathes of land east of the Jordan River (which later became the territory for the tribes of Reuben and Manasseh). But when they requested permission for peaceful passage through the land, the rulers came out looking for a fight. King Sihon of the Amorites gathered his army and attacked. The Israelites, fighting a defensive war, overcame the Amorites and conquered their land, which included many villages and cities (Numbers 21:21-25). The same thing happened later against Og, king of Bashan—the Israelites fought a defensive war and conquered his territory (which included 60 cities). This saw a wealth of territory east of the Jordan River suddenly and miraculously turned over to the Israelites.

The Israelites conquered the Amalekites in a defensive battle, after they were suddenly set upon in the wilderness (Numbers 17:8-16). The Israelites fought against and conquered the Midianites because of the widespread death and destruction brought upon them by their antagonism (Numbers 25). Defensive battles were fought against kings of the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites (Joshua 9:1). A further defensive battle was fought against a Canaanite alliance so great that the belligerents were “as the sand that is upon the sea shore in multitude.” These were all miraculously defeated and their land possessed by the Israelites.

And for a final case of “Israelites vs. Canaanites,” we jump ahead to the time of King David. The Jebusite-Canaanite tribe still dwelt in Jerusalem. Somehow, they had been allowed to remain in the land, occupying their powerful stronghold Jebus. The inhabitants of the city mocked and scorned King David, claiming that the “blind and the lame” would be able to defend the powerful city against him. David’s men swiftly defeated the city by crawling up into it through a narrow gutter. Thus the Jebusites were expunged from the territory. Or were they? Toward the end of David’s life, we read of a Jebusite by the name of Araunah, living and farming just north of David’s palace in Jerusalem. This Araunah was named a Jebusite king (2 Samuel 24:23). He had graciously been allowed to continue owning land within Jerusalem. David, at the end of his life, desperately required the land of Araunah upon which to build an altar to stop a massive plague. Araunah wanted David to have it free, along with oxen and equipment. But David firmly refused. He purchased the land and equipment from Araunah at full price. This, for land directly abutting the royal palace. What other history parallels this kind of benevolence toward a Canaanite ruler? Surely very few, if any.

As a whole, Israel wasn’t aggressive enough. Judges 1 contains a long list of Canaanite areas that should have been conquered—but because of Israelite complacency, were not. These remaining Canaanite tribes would later cause a whirlwind of trouble for the Israelites, especially during the time of the judges.

Canaan Controlled by Evil Imperialists

The story of the Israelites conquest of the Promised Land is not one of a powerful tyrannical people sweeping in and butchering a once-free population. Actually, the Canaanites were decidedly not free. They were under the yoke of an overbearing imperialist power: Egypt.

The domineering and aggressive Egypt sporadically swept into the land, violently destroying Canaanite cities. (Archaeology shows examples of this, particularly in the century before the Israelites’ arrival.) The Canaanites who were spared became vassals—their kings taking on more of a “mayoral” role. The pharaoh demanded the utmost respect and godly worship from his vassal “mayors.” Letters discovered to the pharaoh from Canaanite leaders start out addressing him with such platitudes as the following:

To the king, my lord, my god, my sun … I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, seven times and seven times. I am the dirt under the sandals of the king, my lord. My lord is the sun who comes forth over all lands day by day, according to the way of the sun, his gracious father, who gives life by his sweet breath and returns with his north wind; who establishes the entire land in peace, by the power of his arm: who gives forth his cry in the sky like Baal, and all the land is frightened at his cry. The servant herewith writes to his lord that he heard the gracious messenger of the king who came to his servant, and the sweet breath that came forth from the mouth of the king, my lord, to his servant—his breath came back! Before the arrival of the messenger of the king, my lord, breath had not come back; my nose was blocked. Now that the breath of the king has come forth to me, I am very happy.

“Endearing” oratory to the pharaoh also includes the following:

If the king wrote for my wife, how could I hold her back? How, if the king wrote to me, “Put a bronze dagger into your heart and die,” could I not execute the order of the king?

This kind of banality from the Canaanite leadership was quite common in their correspondence with the narcissistic ruler of Egypt. Several rulers in Canaan reuse many of these phrases—surely their use must have been enforced by the pharaoh.

As Israel swept through the Promised Land, Canaanite leaders within the land sent desperate, impassioned pleas to the pharaoh to send help to defend them. Many dozens of letters have been discovered and are today known as the Amarna Letters. But their cries fell on deaf ears. No Egyptian help was sent.

Contrast the following example. The Israelites, as they were entering the Promised Land, were deceived into a peace treaty with the Gibeonites. Gibeonite messengers were sent to Joshua, lying that theirs was a faraway city outside of the allotted Israelite Promised Land, and secured for themselves a peace deal. In fact, Gibeon was a nearby city located well within the territory of Canaan that the Israelites were commanded to conquer. The Israelites were stuck—they had made an oath to the inhabitants that could not be broken (Joshua 9).

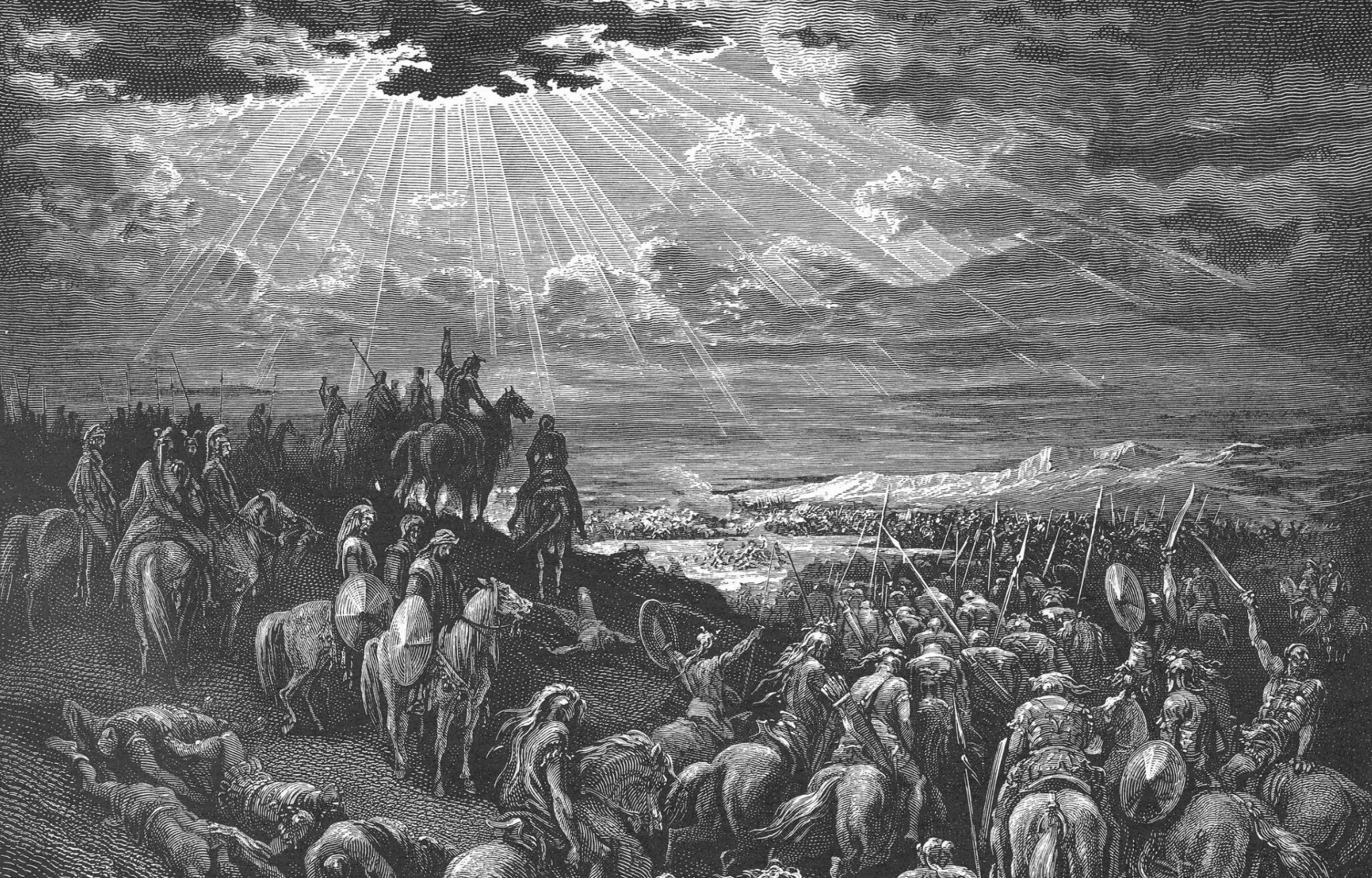

After this, Gibeon was set upon by surrounding Canaanite armies, aiming to punish them for their allegiance. The leaders of Gibeon pleaded with the Israelites for help. Joshua and the Israelite army swept in to the defense of Gibeon. In the ensuing conflict, while defending these Gibeonites, the Israelites pushed back the Canaanite armies and conquered more of their territory in the process. Again, vast amounts of land were won while fighting a defensive war, and in this case not even in defense of themselves but in defense of Canaanites! And in the ensuing conflict, these belligerent Canaanite armies weren’t just slaughtered by the Israelites—God actually rained down giant stones (perhaps hailstones), killing them (Joshua 10). Further, God caused the sun to “stand still” in the sky so that the Canaanites couldn’t flee under the cover of darkness. A miraculous victory—in the aim of defending a Canaanite tribe.

At the end of the day, the conquest of the Promised Land was not just a blow to the Canaanites—it was a mighty blow to the Egyptian empire. Canaanites who served under the Israelites were much better off than they were under the Egyptians. (It’s a possibility that the Gibeonites became what were later known as the Nethinims, a people living in Jerusalem and serving in important jobs relating to the temple service.) Israelites did not own “slaves”—they were expressly warned of such, as they themselves had been a slave people—though they did have servants. God provided an extremely strict set of rules for servants, enforcing proper treatment, pay, and freedoms for those in the employ of the Israelites (again, a separate study). Of course, just like with the conquest of Canaan, critics (including Barack Obama) cry foul and accuse Leviticus of appropriating slavery.

If foreign-born “strangers” wanted to become part of the Israelite nation and abide by the same laws, they could do so and would be treated on the same level as their fellow Israelite citizens. These are hardly the actions of a nation of tyrannical imperialists milking dry a helpless subjugate slave-class.

Canaanite Religion

It is true that God wanted the Canaanites to be wiped out. Given all of the above points—the fact that much of Canaan originally belonged to the Israelites and that much of it was reconquered through defensive battles—God did still intend to bring utter destruction upon the inhabitants of the Promised Land. Deuteronomy 20:16-17 says:

Howbeit of the cities of these peoples, that the LORD thy God giveth thee for an inheritance, thou shalt save alive nothing that breatheth, but thou shalt utterly destroy them: the Hittite, and the Amorite, the Canaanite, and the Perizzite, the Hivite, and the Jebusite; as the LORD thy God hath commanded thee.

Why would God command the slaughter of the Canaanites? Was it just so the Israelites could have more territory? Was it just because God preferred one race over another? Definitely not! The next scripture goes on to explain why: “that they teach you not to do after all their abominations, which they have done unto their gods, and so ye sin against the Lord your God.” (verse 18).

Understanding the debauched lifestyle and religion of the Canaanite people helps us to understand why God condemned them. Put simply, Canaan was a veritable reincarnation of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the land was to face the same penalty of utter destruction.

Leviticus 18 contains a long list of evil practices that the Israelites were to avoid—and specifically states that these were the rampant practices of the Canaanites (verse 24). These “traditions” included sexual acts between members of the same family, including incest and adultery. They included homosexuality and bestiality. Perhaps most egregious of all, they included child sacrifice. Due to these horrific sins, God states that the “land vomited out her inhabitants” (verse 25).

Archaeology sheds some light on the practices of the Canaanites. Much of our archaeological knowledge of Canaanite religion comes from texts discovered at the northern city of Ugarit. The texts confirm that Baal was one of the chief Canaanite gods. Baal is often associated with his ritualistic mother-cum-mistress, Asherah. Temple prostitutes served as earthly “representatives” of the gods. Ray Vander Laan writes in his article “Fertility Cults of Canaan”:

Pagans practiced “sympathetic magic,” that is, they believed they could influence the gods’ actions by performing the behavior they wished the gods to demonstrate. Believing the sexual union of Baal and Asherah produced fertility, their worshipers engaged in immoral sex to cause the gods to join together, ensuring good harvests. This practice became the basis for religious prostitution (1 Kings 14:23-24 [see also 1 Samuel 2:22]). The priest or a male member of the community represented Baal. The priestess or female members of the community represented Asherah.

The Canaanites attempted to replicate the behavior of their gods. Baal would fornicate with both his mother, Asherah, and his sister Anat. The ancient texts carefully prescribe the ritualistic manner in which temple orgies were to take place. Baal was also said to engage in bestiality, so the same would be done by the population. Evidence from ancient Egypt—a heavy influence on Canaan—even prescribes idyllic species of animals.

Also evidenced by the Ugaritic texts was the cult of the dead. The dead were summoned, through demon-possessed religious acts, to attend a banquet. This was ostensibly a drunken orgy. This event—a licentious “Halloween” of sorts—was meant to elicit the spiritual power and protection of the dead.

From many early historians (such as Cleitarchus, Plutarch, Diodorus), we have descriptions of the child sacrifice rituals of the Carthaginians. These were Phoenicians who are known to have directly continued the Canaanite religion. According to the historians, children—up to at least 4 years old—would be offered en masse at Carthage, placed one by one into the outstretched bronze hands of the god before them. The children would be burned alive in the hands and would slip through the fingers into a cauldron below. It is said that the lips of the child would quickly shrivel away due to the intense heat, giving the impression that the child was grinning. The sacrificial area would be filled with the noise of drums and flutes, drowning out the screams. If devotees did not have their own children that they could offer, they would simply purchase children from the poor of the city.

Many of these traditions are simply too barbaric to describe in this article. Several articles provide in-depth information; one good place to start would be Prof. Clay Jones’s article “We Don’t Hate Sin So We Don’t Understand What Happened to the Canaanites,” together with his sources.

To put it in more “common” terms, when it comes to the Canaanites, think the Aztecs or Incans (who, according to some studies, may even be descended from ancient Canaanites)—widespread purveyors of human sacrifice (along with the standard sexual deviance). Canaan was a cesspool of child sacrifice and sexual deviancy with virtually anything breathing—be it with family members or family pets. Such nationwide behavior couldn’t be overlooked. Punishment was due. In this way, the invasion of Canaan wasn’t to be just any regular military operation, but rather a nationwide execution of divine judgment.

Some may ask, though, was God too hasty? Could He have given the Canaanites more time to turn things around? Was He simply looking for excuses to rid the Canaanites from the land in order to repopulate it with Israelites?

Far from it. God told the patriarch Abraham, a full 500 years before the Exodus, that his descendants would have to wait four centuries to enter the Promised Land. Why? “For the iniquity of the Amorite is not yet full” (Genesis 15:16). God, in His mercy, postponed their destruction for nearly another half-millennium because the people of the land weren’t yet totally saturated in perversity.

Such was the eventual glut of sins in the land that God stated one of the main reasons for Israel even entering the Promised Land was for the express destruction of the wicked inhabitants—not because of Israel’s righteousness (Deuteronomy 9:4-5).

No Respecter of Persons

The Israelites’ conquest of the Promised Land is not about a God who hated the Canaanites and desired to destroy them in favor of a much “better” nation. It is instead about “blessings for obedience” and “curses for disobedience” (Leviticus 26; Deuteronomy 28). It was the same basis for Noah’s Flood. It’s the reason for what happened to Sodom and Gomorrah. It’s the reason for the prophesied Great Tribulation of the near future, before the coming of the Messiah. God, as the Bible repeatedly emphasizes, is “no respecter of persons.” And so God punished the Canaanites for their gross sins and replaced them with the Israelites.

But He did the same to the Israelites.

God gave Israel a chance. The Israelites of the northern kingdom had around 700 years to prove themselves after entering the Promised Land. Every single king of the divided northern kingdom was a pagan. Canaanite-like idolatry and child sacrifice were rife. The sins of the nation could not go unpunished. And so, just as with the Canaanites, God sent the Assyrians (“the rod of Mine anger”—Isaiah 10:5) to destroy their cities and uproot their inhabitants. The mighty northern kingdom took on a now infamous name: the lost 10 tribes. Those were the fortunate ones—the deportees. Many of their fellows faced what the Assyrians were known best for: gratuitous torture, including dismemberment, skinning and disembowelment.

The southern kingdom of Judah fared only a little better. The Jews lasted about 140 years longer, due to some righteous rulers, before their egregious sins made it necessary to receive the same punishment. The Babylonians swept in and destroyed the nation, uprooting nearly all the inhabitants and carrying them away into captivity.

God is no respecter of persons. The same sins bring the same punishments.

So Why the Outrage?

The true story of Israel’s conquest of Canaan is much different from popular conception. God freed the enslaved Israelites from an evil, imperialistic cult-nation led by a lineage of incestuous god-kings, crippling that nation at the same time. He led His people to the land He had promised to the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—land that had then been purchased and owned by the patriarchs, and legally turned over to Egypt during the Great Famine. At the time of the Exodus, the land was occupied by a vassal Canaanite population deeply rooted in human sacrifice and other grossly morbid and erotic acts. The Israelites were originally intended to claim the land without fighting. But due to sin, faithlessness and self-reliance, God allowed the Israelites to take the land the hard way—by military means. Thus Israel entered Canaan, returning to the land their forefathers had purchased, joining a contingent of their own fellow Israelites who were likely already there—and along the way, accepting those strangers who would join their community, showing favor to those who showed favor to them, condemning those who condemned them, and taking vast swathes of territories through fighting defensive battles against ruthless Canaanite kings.

And at the end of all of it, Israel ended up committing the same sins and reaping the same result.

So why the outrage—the cries of “foul play” against the Israelites, against God? Why the ignorant vitriol from such renowned professionals as Dawkins? Is our moral standing that much higher than God’s?

Or maybe it is that, deep down, we are just like the Canaanites. As Professor Jones stated in his above-mentioned article,

[W]e do not appreciate the depths of our own depravity, the horror of sin, and the righteousness of God. Consequently, it is no surprise that when we see God’s judgment upon those who committed the sins we commit, that complaint and protest arises within our hearts: “This is divine barbarism!” or “This is divine genocide!”

Perhaps, in our societies, there’s more of a gloss. Perhaps it’s easier to ignore. But it’s there. Take the following statistics from the United States alone—the leading light of the world—the “city set on a hill”: 1 million prostitutes; 40 million regular porn users; 25 million illicit drug users; 10 million adults who identify as LGBT; 8 million practitioners of witchcraft; over 200,000 registered witches; between 50,000 to 100,000 Satanists; 50,000 “vampires,” thousands of which indulge in blood; over 320,000 victims of rape and assault each year; 47 murders per day in 2016—over 17,000 in a year; one child abused every 10 seconds, missing every 40 seconds, raped every 2 minutes, killed every 3 to 6 hours from abuse; over 100,000 children prostituted annually. And if that doesn’t qualify as child sacrifice: Over 2,500 abortions every day (nearly 1 million per year). That’s just in the U.S. Worldwide: over 1.5 billion since 1980. That’s just the murder of unborn children. Even the ritualistic sacrifice of newborns and toddlers continues in certain parts of the world—a practice vehemently defended by leading lawmakers and scholars.

What kind of moral standing do we mortals have to condemn the great God for supposed “injustices” more than three millennia ago?

Those are terrifying statistics. And not just for the victims—but for all of us. Because destruction is coming. Just as sure as it came for the ancient Canaanites.

A Story of Mercy

At the end of the day, God’s destruction of the Canaanites, as well as the prophesied soon-coming destruction and judgment on this Earth, is an execution of mercy. The Bible, clearly condemning such Canaanite (and modern) practices, actually shows that they lead to such permanent and irreversible mental and spiritual damage that, if allowed to continue, there can be no redemption for the thus-polluted mind in this life or the next. Thus, the quite literal ending of such cultures in this life is an act of mercy, in preserving those individuals for a shot at redemption in the next life.

Many believe that this life is all that there is. Extreme lengths are taken to prolong life for only a few additional months or years. But this life is merely a shadow—a blip on the radar screen compared to our future lives, post-resurrection, as described in numerous verses throughout the Bible. God certainly cares deeply for our well-being in this life. But our behavior in this life frames the course of the next—and that is the real, true life that God is primarily concerned about, and we should be too. Unfortunately, it is a concern that far too many push aside until they are on their deathbeds.

God, as our Creator, reserves total right to punish us for our sins. But He does so in mercy. Ezekiel 33:11 makes clear God’s true emotions on the matter of divine punishment and correction, His feelings toward the Canaanites 3,500 years ago, and His feelings toward you and me today:

As I live, saith the Lord GOD, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live; turn ye, turn ye from your evil ways; for why will ye die, O house of Israel?