Jerusalem’s ancient temples have been described in various texts as veritable palaces of grandeur. The biblical account of Solomon’s temple would make it arguably the most impressive structure ever built—especially given that it was covered in 100,000 talents of gold (around $300 billion in today’s value). And while of lesser beauty, the second temple—built after the destruction of the first, and revamped by King Herod—was still an impressive, dazzling building covered in precious metals and ornamentation. The temples were the central location of worship for the true God, and were considered His “dwelling place.”

Nowadays, there is a new term in vogue: “temple denial.” The notion that the temples never existed, or at least existed elsewhere in the country, has become popular in Islam—especially thanks to the controversy over the Temple Mount, al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, in particular, brought this to the fore during his “peace talks” with Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and United States President Bill Clinton—promoting the idea that the Jewish temples were actually located at Nablus, a city deep within the northern West Bank. According to Israeli diplomat Dore Gold, Arafat’s comments sparked widespread temple denial across the Middle East, something that even “slipped into the writing of Middle East-based Western reporters.”

The question of the temples really gets to the heart and core of Jewish existence. Temple denial is a denial of Jewish heritage and historicity.

There is plenty of legitimate debate as to where, precisely, the temples were located within the bounds of Jerusalem. We won’t get into that here. For this article, we’ll look at the wider question: whether or not the temples existed at all and whether or not they were located, as the Bible repeatedly affirms, in Jerusalem.

First, though, we’ll begin with the building that preceded them all: the tabernacle.

The Tabernacle

The tabernacle was established in Shiloh after the Israelites entered the Promised Land. It is featured throughout the books of Judges and Samuel as the central place of worship before the construction of the temple. Below is a fantastic 3d animation of the tabernacle by Immersive History. (Embedded under each heading in this article—The Tabernacle, The First Temple, and The Second Temple—is an animated video by this company. There are some inaccuracies, such as the depiction of altar stairs, and the representation of cherubim—but on the whole, these are impressive videos that give a pretty good idea of what these edifices would have looked like while in use.)

No remains of the tabernacle itself have been discovered. After all, it was a tent-structure—a temporary dwelling, never designed as a permanent installation. Further, Shiloh was utterly destroyed throughout history, leaving little remains—the Prophet Jeremiah attests to this (Jeremiah 7:12-14; 26:6-9). However, there is supporting evidence that has been discovered, proving the existence of the structure.

Sacrifices

Proof for the presence of the tabernacle at Shiloh is primarily in the form of sacrificial remains. Masses of sacrificial waste have been found dumped to the side of the tel. This waste dates to the precise period within which the tabernacle was in operation (end of the second millennium b.c.e.). Furthermore, these sacrificial remains belonged uniquely to kosher animals. This represents a marked difference to the surrounding Canaanite and Philistine cultures. Clearly, Shiloh was an important religious center for a new method of worship: that brought by the Israelites.

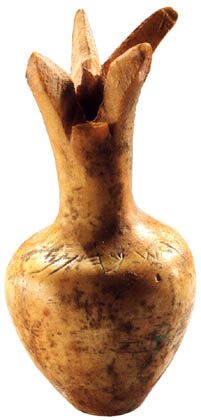

Pomegranate

During their 2018 excavations, director Scott Stripling’s team discovered a small white ceramic pomegranate, a few centimeters in length, bored through at one end in order to be hung from a string. The pomegranate is a well-known motif that featured in Israelite tabernacle and temple worship (e.g. Exodus 39:24-26; 1 Kings 7:18-20). The Exodus account describes the high priest’s outfit having a string of small bells and pomegranates hanging from the hem. This small pomegranate, then, may have been used for some such religious decoration. It matches another object found at the site nearly 100 years ago—this badly broken object can now be identified as another pomegranate, thanks to the recent parallel discovery.

So while no material of the tabernacle itself has yet been found (again, it was a tent), associated evidence such as that described above helps to confirm Shiloh as Israel’s original religious center and site of the tabernacle, as described in the Bible.

The First Temple

As with the tabernacle, there is as yet a paucity of direct evidence for the temple structure itself. However, there is a growing, irrefutable body of corroboratory evidence, as well as some intriguing (yet still debated) discoveries that may well mention the temple itself.

Copper Mines

Excavations have been ongoing at Timna, in Israel’s southern Negev region, for over a decade. Part of the ancient kingdom of Edom, this area houses the earliest known copper mine in the world. Excavations have shown that copper production here peaked during the 10th century b.c.e.—right at the time of Israel’s kings David and Solomon.

The Bible describes Israel actually controlling this entire land of Edom at this time—and thus the output of the mines. 2 Samuel 8:13-14 read:

And David got him a name when he returned from smiting the Arameans in the Valley of Salt, even eighteen thousand men. And he put garrisons in Edom; throughout all Edom put he garrisons, and all the Edomites became servants to David. …

Numerous pieces of 10th-century b.c.e. weaponry and a 5-meter-high fortified wall have been found in the Timna region, helping to corroborate this passage. Alongside the wall, a heavily defensed gatehouse and donkey stable were found, dating to the same period. When some preserved, 3,000-year-old donkey manure was examined, it showed that their feed (of straw, hay and even grapes) had originated from the Jerusalem area. This provides evidence of a convoy of materials to and from Jerusalem, together with the peaking copper production. The Bible provides a clear connection of this phenomenon to the construction of the first temple, with the quantity of material being so great that “the weight of the brass [an alloy of copper] could not be found out” (1 Kings 7:47).

Alongside these recent discoveries, pieces of beautifully dyed clothing were found at the mines. These fabrics also date to the 10th century b.c.e. and show that, to the surprise of the excavators, these mines were operated by finely dressed craftsmen, rather than the assumed typical ragtag team of slaves. Many scoff at the biblical description of the immense grandeur and wealth of Solomon’s kingdom, but the fact that mines were being operated by opulently clothed individuals reinforces the biblical narrative.

Tyrian Aid

The Bible describes the Phoenician King Hiram as a close friend of King David, who assisted David in the construction of his palace. After David’s death, Hiram provided an extraordinary amount of assistance to Solomon in constructing the temple, along with another new palatial structure (1 Kings 5).

A royal sarcophagus was discovered at the Phoenician city of Byblos, dating to the 10th century b.c.e. An inscription on the stone coffin reads, “Ahiram, King of Byblos.” This may have been the very individual that assisted Solomon in building the temple. The Bible does specify Hiram as “king of Tyre.” Byblos is a city further north along the coast—still, the site may likely have been under the same king’s jurisdiction within wider Phoenicia. Further, there is evidence of crossover in Phoenician regional names: Solomon refers to Hiram’s people as “Sidonians” (1 Kings 5:20). Sidon was another major city, near Tyre, within Phoenicia. So it is very possible that the 10th-century b.c.e. Hiram, king of Tyre and Sidon, was also one and the same as the 10th-century b.c.e. Ahiram, king of Byblos.

Even if this is a different individual, the inscription confirms biblical accuracy in the use of the name “Hiram” in the royal Phoenician court during this period.

Jeroboam’s Altar

The Bible recounts that during the days of Solomon’s son, Rehoboam, the northern 10 tribes of Israel broke away under the leadership of Jeroboam. One of the early worries for King Jeroboam, though, was Jerusalem’s temple. This was the center of worship, and all offerings from around Israel were to be brought to the temple. Jeroboam worried that this would cause the 10 tribes to desire to return under the rulership of the southern kingdom of Judah. So the new king set up a place of pagan worship at Bethel in the south and at Dan in the north to make religious travel more “convenient” and to keep his people within the northern kingdom. These places of worship featured an altar and a golden calf.

The place of worship at the northern city of Dan has been found. Tel Dan features a massive raised platform (probably atop of which the golden calf stood), and before it a massive altar that originally stood about 10 feet tall, with two staircases leading up to its sacrificing platform. Various sacrificial implements were found at the site, attesting to its mass pagan use. This temple complex dates within the 10th to eighth centuries b.c.e. (the general period of the existence of the northern kingdom of Israel), exhibiting several phases of reconstruction.

So while Tel Dan’s altar is not direct evidence of Jerusalem’s temple, it certainly provides corroboratory support, since the whole reason it existed was to replace the temple in Jerusalem.

Before leaving the subject of altars, mention must be made of a “four horned” altar discovered in Beersheba (possibly eighth century b.c.e.). This was the first such altar ever unearthed in Israel, and corroborates numerous scriptures requiring altars to have a “horn” on each corner, as would have been the case with the Jerusalem altar. (Other examples of such altars have since been found at several sites throughout Israel.)

Tribute

The Bible relates that Hezekiah was a righteous king over Judah at the end of the eighth century b.c.e. He was famous for his religious reforms—destroying pagan places of worship and refurnishing the temple in Jerusalem. Ample evidence of Hezekiah’s pagan “purges” has been found (notably, at Lachish).

However, later in his reign, Hezekiah’s faith wavered. The Assyrians were invading Judah, and Hezekiah attempted to pay them off. Sennacherib demanded 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold. Hezekiah pillaged the temple, going so far as to strip gold from the doors and pillars (2 Kings 18:14-16).

Remarkably, receipt of this transaction has been found, documented on Sennacherib’s prisms. “As for Hezekiah, the terrifying splendor of my majesty overcame him … In addition to the thirty talents of gold … [continues to list a variety of other items, including silver] which he had brought after me to Nineveh, my royal city. To pay tribute and to accept servitude, he dispatched his messengers.”

Again, while this discovery of itself does not “prove” the temple, it does confirm the biblical account, accurate down to the weight of gold—and where did that gold come from? The temple!

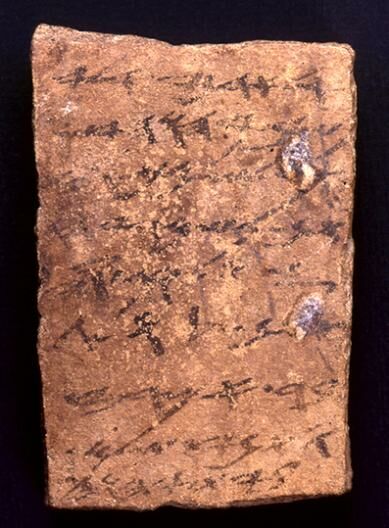

House of YHWH

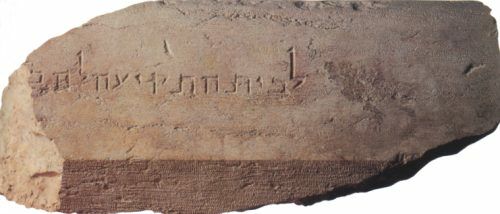

This fascinating ostracon (a pottery sherd with writing on it) was discovered at Tel Arad, dating to the early sixth century b.c.e. (just before the fall of Judah). It reads:

To my lord Eliashib: May yhwh inquire after your well-being. And now, give to Shemaryahu a measure (of flour), and to the Kerosite you will give a measure (of flour). And concerning the matter about which you commanded me, it is well. He is staying in the house of yhwh.

The name of Jerusalem’s temple was the “house of yhwh,” the tetragrammaton name of God. And it did have chambers in it, within which one could stay. However, there were also several pagan “high places” around the land, attested to in the Bible and in archaeology. These were known as “houses of yhwh,” the same as the temple—and one was in Tel Arad. Still, it seems likely that this ostracon refers to the temple in Jerusalem. This is based on the assumption that the letter was found where it had been delivered to—Eliashib, in Tel Arad—and thus, the house of yhwh would logically not be the one at Tel Arad. Further, the unspecified location of this house may thus imply it to be the most well-known and only true house of yhwh—the temple in Jerusalem.

At the very least, the inscription confirms such a thing as a “house of yhwh.” Where did such a term, such an idea, come from? Surely, it must have been from the official religious center of worship—from the original house of yhwh, the temple in Jerusalem.

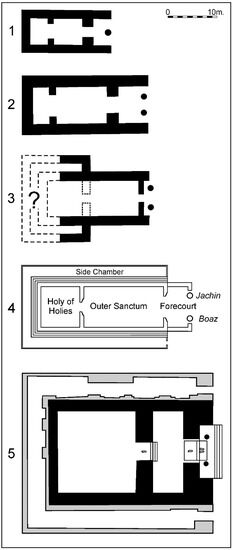

Parallel Temples

Further evidence for Solomon’s temple can be found in numerous other later temples that were built in and around Israel, matching closely to the layout and design of the temple described in 1 Kings 6. All these parallel temples are, obviously, pagan—certainly some though, if not all, took some kind of inspiration from the First Temple.

There is the “house of yhwh” at Tel Arad, as mentioned above. The foundational outline of this temple has been discovered, and it dates to roughly 100 years later—the ninth century b.c.e. Then there’s a similar temple at Tel Motza—this one has been dated to the eighth century b.c.e. The Jewish outpost at Elephantine contained a copy of the temple—the original dating for the construction of this one is uncertain, but it likely dates to the seventh to sixth centuries b.c.e. Then there’s the Mount Gerizim temple, built by the Samaritans as their own answer to the Jerusalem temple—archaeologists have dated this one to the fifth century b.c.e.

These temples were all built either in Israel or by Israelites—thus by those who would have had a knowledge of the Jerusalem temple. Another worth noting is the Tel Ta’yinat temple. This one dates to the ninth century b.c.e., and is located in southern Turkey, right on the border with Syria. Given that the biblical account shows Solomon’s kingdom expanded far north, deep into Syrian territory (as far as Hamath), and given the renown of the Solomonic temple, it would not be surprising for a copycat temple to have been established somewhat further north. Again, these temples are all close parallels to the biblical appearance—rooms, dimensions, etc—of Solomon’s temple.

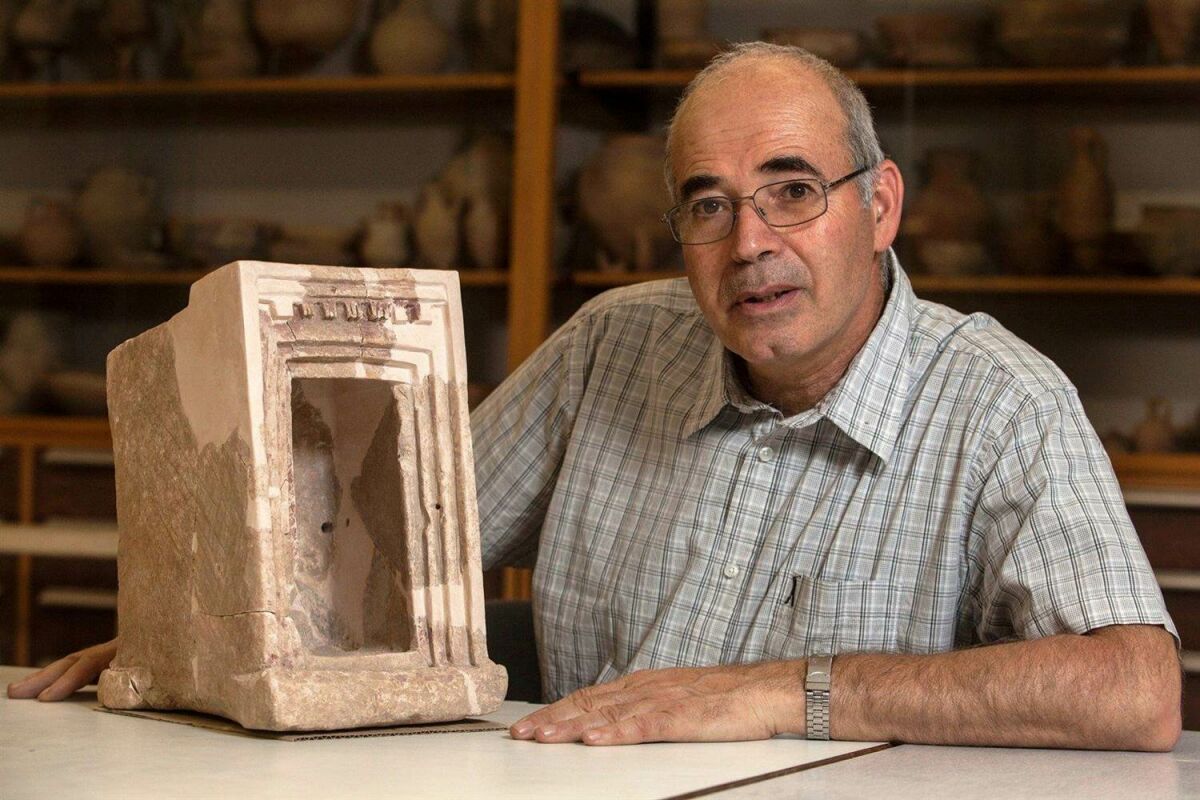

Khirbet Qeiyafa Temple Model?

During excavations at the site of Khirbet Qeiyafa in 2011, a peculiar, carved, open stone box was discovered (see below). Decorated open-sided shrine vessels made of clay (and that would typically hold some kind of image or god) have been discovered around sites in ancient Israel–Philistia, but this one was unique—and not just for being made of stone. This 10th-century b.c.e. artifact exhibits design parallels that match those of both the first and second temples.

There are three recessed doorposts on the stone model. 1 Kings 7:4-5 describe Solomon using this style of architecture for his palatial building near the temple—it is likely he used the same technique for the first temple itself. Further, the Mishnah (Middoth 3, 7) shows that the doorframe of the second temple was built in the same manner.

The model door opening itself is 20cm tall x 10cm wide. The Mishnah describes the second temple as having a door 40 amah tall by 20 amah wide (Middoth 4, 1; it is important to note that much of the design of the second temple was influenced by the first).

Thirdly, the model has seven protruding squares beneath the roof. Each square is divided by two lines, into three small rectangles. It is clear that these are meant to represent the ends of wooden crossbeams supporting the roof. This depiction is actually a comparatively “advanced” design feature called a “triglyph,” appearing in Classical Greek buildings some 400 years later. The fact that the design was already known at such an ancient time—the 10th century b.c.e.—indicates that the early Israelite kingdom was far more advanced and influential in construction and design than first believed.

And this triglyph construction technique is almost certainly mentioned in the description of Solomon’s “forest of Lebanon” (1 Kings 7:2-3), in the description of Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:5), and in Ezekiel’s description of the temple (Ezekiel 41:6). Translations of these passages are problematic, but when viewed in light of this recent discovery, they make sense. Here is Prof. Yosef Garfinkel (director of the Khirbet Qeiyafa excavations) and Madeleine Mumcuoglu’s translation of Ezekiel 41:6:

And the planks were organized three together, as thirty triglyph-like groups, placed on top of the wall, around all the building, without being integrated into the walls of the building.

It would be fair to surmise that the inspiration for the Classical Greek triglyph came from an impressive Israelite building that used such techniques—and what more impressive, influential building than the temple itself?

Thus, not only do actual buildings parallel the biblical account of Solomon’s temple—parallels can also be seen on a miniature, model level.

Unprovenanced Inscriptions

There are a number of unprovenanced inscriptions that are regarded as possible (or even likely) forgeries. However, there is still hot debate surrounding them, and as such we mention them briefly here.

First is the pomegranate inscription. This is a small carving of a pomegranate (from hippopotamus bone), which would have possibly adorned a priestly scepter. Near the crown of the pomegranate is an inscription reading “Belonging to the House of yhwh, holy to the priests.” The pomegranate itself has been proved to be over 3,000 years old. However, authenticity of the inscription itself has been hotly contested.

Another item is the Jehoash Inscription. This piece is a relatively lengthy record of Jehoash’s renovations of the temple in Jerusalem. The artifact appears more likely to have been a forgery, but the jury is still out, despite intensive, microscopic-level investigations.

Finally, there is the Three Shekel Ostracon. This artifact, widely viewed as a forgery, is a small pottery sherd bearing an inscription relating to a donation to the house of yhwh.

Solomon’s Buildings

Finally, mention must be made of the giant structures that have been discovered in Jerusalem, dating to the 10th century b.c.e.—the time that the Bible states the temple was built. One—a palatial structure matching the biblical description of the palace of David (2 Samuel 5); and two—a large royal structure and powerful fortification wall matching the biblical account of Solomon’s northward expansion of the city (e.g. 1 Kings 9:15). And if material remains match these biblical structures, why should not the temple have also existed, described in the very same passages?

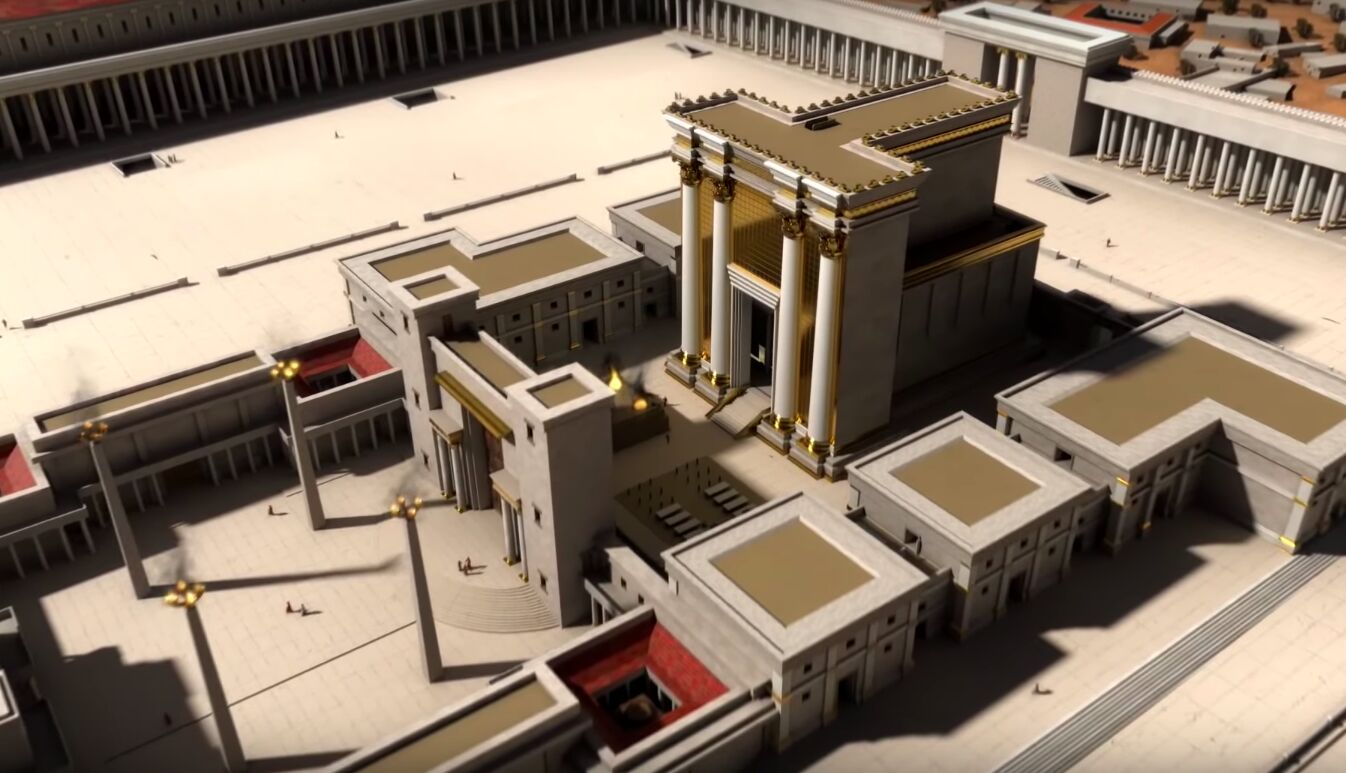

The Second Temple

Generally, when one thinks of the second temple, it is of the building constructed by King Herod at the end of the first century b.c.e. Materials belonging to this structure have been discovered, along with significant eyewitness accounts of it. However, the second temple was initially constructed much earlier—at the end of the sixth century b.c.e. (Herod’s efforts constituted a massive overhaul, 500 years later.) So as such, we begin this section with an artifact relating to Zerubbabel’s construction of the second temple.

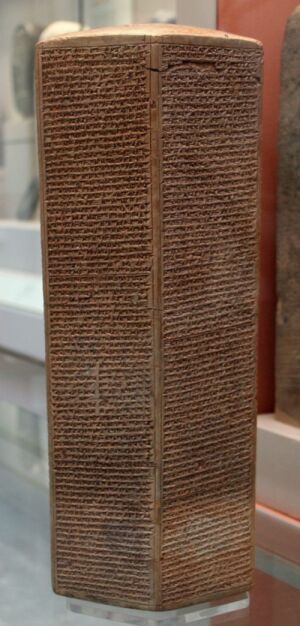

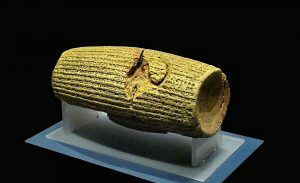

Cyrus Cylinder

Ezra 1 states that after the Persian King Cyrus conquered the Babylonian Empire, he sent out a decree allowing Jewish captives to return to the Holy Land and rebuild the temple. “Who is there among you of all his people? his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem, which is in Judah, and build the house of the Lord God of Israel …” (verse 3). This magnanimous, almost unheard-of ancient gesture has been corroborated by the Cyrus Cylinder.

The Cyrus Cylinder inscription essentially resembles Cyrus’s commands to the Jews—only, to the conquered Babylonians. It contains a lengthy text allowing the Babylonians various freedoms to live and rebuild their temples, under the authority of the Persian Empire. As such, it provides supportive evidence that the same decree went out to the Jews under Persian rule, allowing them to rebuild their temple in Jerusalem.

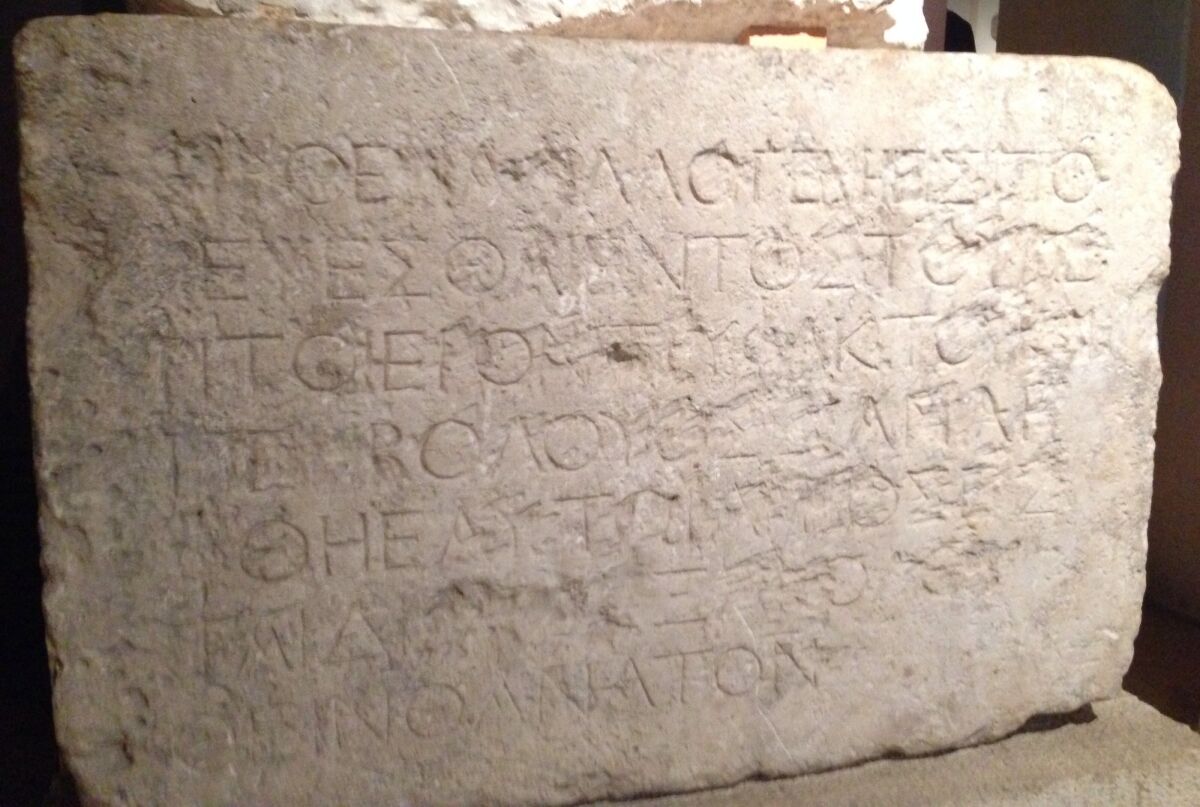

Warning Inscriptions

We now come to the most well-known form of the second temple—that rebuilt by King Herod. Detailed, eyewitness accounts of this building are documented by such individuals as the first-century historian Josephus and philosopher Philo, as well as in the Mishnah (tractate Middoth, which describes the entire layout and measurements of the building).

Josephus wrote that the second court of the temple was surrounded by a stone wall, and upon it stood inscription stones “at equal distances from one another, declaring the law of purity, some in Greek, and some in Roman letters, that ‘no foreigner should go within that sanctuary’” (War of the Jews, v.5.2). He further mentioned this warning in his book Antiquities of the Jews: “an inscription, which forbade any foreigner to go in under pain of death” (xv.11.5). Philo also wrote of this prohibition. In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul was accused of violating it, and was narrowly saved from death by intervening Roman soldiers (Acts 21:26-32).

Since the late 19th century, two large stone temple inscriptions have been discovered, corroborating these accounts with the following inscription:

NO FOREIGNER IS TO GO BEYOND THE BALUSTRADE AND THE PLAZA OF THE TEMPLE ZONE. WHOEVER IS CAUGHT DOING SO WILL HAVE HIMSELF TO BLAME FOR HIS DEATH WHICH WILL FOLLOW.

Both inscriptions are in the Greek language. One is complete, and is housed in the Istanbul Museum of Archaeology; the other, an incomplete inscription, is in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Both pieces represent actual, tangible stones of the Herodian temple complex. Both were found in secondary use: one on the north side of the Temple Mount, and another on the west side, reused as part of a tomb wall. David Mevorach, senior curator at the Israel Museum, labels these stones as the “closest thing to the temple we have.”

Donations, Trumpets, Offerings

Another such inscription has been found that almost certainly represents a donation given for the building of Herod’s temple—specifically, the pavement. The stone is broken but the context of the inscription is clear, and mention is made of a high priest, as well as a date for the contribution (circa 18 b.c.e.)—a date that corresponds with the building of the temple. It is probable that a number of these kinds of inscriptions were around the temple complex, like commemorative plaques, mentioning those who made significant contributions to the rebuilding program.

A large incised stone was found at the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, with the inscription, “To the place of trumpeting for ….” This stone block may be related to Josephus’s account of a place where one of the temple priests gave a trumpet signal for the beginning and end of the Sabbath (Wars of the Jews, iv.9.12).

A broken handle of a limestone vessel was discovered at the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount. Written on the handle is the word korban, with a depiction beneath of two upside-down birds. “Korban” represents a sacrifice, and certain birds (doves and turtledoves) were sacrificed at the temple. Further, the Mishna specifically mentions sacrificial vessels marked as korban. Thus, we have a vessel directly associated with temple sacrifices.

Mikvaot

Literally hundreds of mikvaot (ritual purification baths) have been discovered within ancient Jerusalem, many in the City of David and on the Ophel. The large number of these structures indicates the presence of a sacred building in the area—a temple—and the need to cleanse oneself before entering the temple courts. These ritual baths date from the Hasmonean Period, on through the Herodian. The Hasmonean Period is important in that it represents a time when the pagan Seleucid rule over Jerusalem was overthrown and the Maccabees cleansed Jerusalem and the temple, in particular, reinstalling proper sacrifice and worship. Mikvaot (plural of mikveh) would have played a large role in this process.

Arch of Titus

Much has been written about the 70 c.e. destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, with Josephus’s eyewitness account as the most lucid. And one of the most vivid testaments to the temple’s destruction is the Arch of Titus.

The arch is a massive honorific monument, built in Rome circa 82 c.e. by Emperor Domitian to commemorate the victories of his recently deceased brother, Titus. On the arch are displayed a number of scenes, most notably a procession carrying away treasures from the temple, including the grand menorah. This stone carving is another piece of “concrete” proof of the temple in Jerusalem, its treasures and the massive Roman invasion that crushed the Jewish rebellion.

In fact, so vast was the amount of treasure pillaged from the temple and wider Judea by the Romans that researchers believe it allowed the building of Rome’s famous Colosseum. The extravagant and iconic Colosseum was constructed two years after the sack of Jerusalem. A large Colosseum stone altar inscription was discovered, declaring that the building had been constructed “with the spoils of war.” This is taken primarily (if not exclusively) to mean the spoils of the war against the Jews. (Further, the Arch of Titus was built right next to the Colosseum.) These must have been quite the spoils—given not only the impressive nature of the Colosseum, but also the fact that the earlier Emperor Nero had left behind a mighty budget deficit for his succeeding emperors.

That this most famous building of the mighty Roman Empire was able to have been built following the plunder of Jerusalem helps attest to just how impressive the holy city and temple truly were.

Bar Kochba Coins

Finally, we can actually get a glimpse of what the original temple looked like. The Bar Kochba Revolt (132–136 c.e.) was another failed attempt by the Jews to break free of Roman rule. The Jews during this time minted a series of revolt coins, stamping rebel imagery over pre-stamped Roman coins.

There were several different Bar Kochba coins—one is of particular interest. On one side was an inscription reading “To the Freedom of Jerusalem”; on the other, an image of the front of the temple. The four-pillared Herodian entrance can clearly be seen. This revolt took place in living memory of the first Great Revolt, when the temple still stood. Thus, the depiction shows a reliable representation (albeit small and poorly crafted) of what the original temple would have looked like. The image between the two central pillars is believed to be a representation of the ark of the covenant.

The Insanity of Temple Denial

For this article, we’ve really looked only at the hard, material evidence. There is additional, textual, historical evidence—eye-witness accounts from people who were there, who saw the temple. Of course, dyed-in-the-wool doubters may dismiss such accounts. What can’t be as easily dismissed is the physical evidence.

Concrete, unequivocal proof exists of the second temple—including building remains. When it comes to the first temple, no such remains have been discovered—but there is so much corroboratory evidence, besides all of the textual and historical references, that it would be ludicrous to claim the first temple did not exist. And evidence points to it having been built right at the time the Bible chronology says—during the 10th century b.c.e. (as shown in particular by discoveries at Timna, Jeroboam’s altar and the parallel temple, “house of yhwh” sites).

Why would it be necessary to “make up” the existence of a temple? Some may doubt the biblical account of the incredible richness of the structure—but to doubt it ever existed?

As stated at the beginning of this article, temple denial has been chiefly popularized by those of the Muslim community. But this is only a new phenomena—it was not always this way. Islamic traditions—as well as the Qur’an itself—variously make mention of a Jewish temple. And a guide to the Haram al-Sharif (Temple Mount) produced in 1925 by the Supreme Muslim Counsel states the following remarkable admission—although back then, it was not so remarkable (emphasis added):

The site is one of the oldest in the world. Its sanctity dates from the earliest (perhaps from prehistoric) times. Its identity with the site of Solomon’s temple is beyond dispute.

Beyond dispute? How times have changed.

But people tend to believe what they want to believe. In the Western world, society has come to accept the term known as “your truth,” as opposed to “the truth.” People have their own narrative, and they fight tooth and nail for it—despite a crushing weight of evidence to the contrary. Such is the case with Holocaust denial. Such is the case with temple denial.

Archaeologist Prof. Gabriel Barkay said:

Temple denial is a tragic harnessing of politics to change history. It is not a different interpretation of historical events or archaeological evidence. This is something major. I think temple denial is more serious and more dangerous than Holocaust denial. Why? Because for the Holocaust there are still living witnesses. There are photographs; there are archives; there are the soldiers who released the prisoners; there are testimonies from the Nazis themselves. Concerning the temple, there are no people among us who remember.

But the stones saw and remember. And as time goes on, as more archaeological work is accomplished, they are speaking their history.