It couldn’t be true. Surely something had been misdated, mistranslated, forged, anything. Surely this ancient stone tablet wasn’t saying what it was saying.

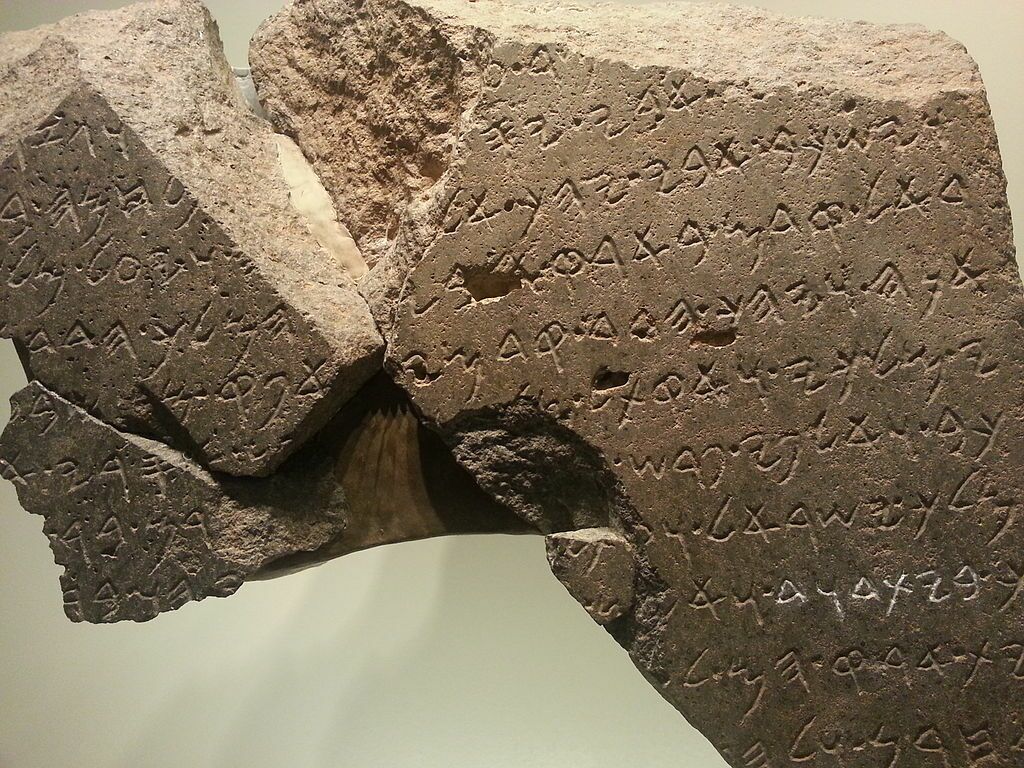

Such was the reaction of some to the Tel Dan Stele, discovered in 1993. There was nothing wrong with the artifact in general. It was a dark, medium-sized, broken victory stone that had been found in secondary use as part of an ancient wall in the northern city of Tel Dan. Its original use had been as a ninth-century b.c.e. celebratory inscription belonging to Syria’s King Hazael, a glorification of his triumphs over Israel’s King Jehoram and Judah’s King Ahaziah. What was “wrong” was the mention of another name on the stele.

The inscription reads (emphasis added):

And I killed two [power]ful kin[gs], who harnessed two thou[sand cha]riots and two thousand horsemen. [I killed Jeho]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel, and I killed [Ahaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g of the house of David. And I set …

According to a number of scholars, David isn’t supposed to have existed—he is just a legend. While later biblical kings had clearly been evidenced by archaeology, nothing had, as yet, confirmed King David’s existence. Their reasoning was that Israel couldn’t have had a strong, unified kingdom under mythical rulers as early as David and Solomon.

Yet this inscription clearly identified not just a man, but an established royal lineage—known as the house of David (BTDWD, as etched onto the stele)—a phrase used 26 times throughout the Bible and finally discovered on a nearly 2,900-year-old stone inscription, unearthed under careful scientific excavation. The discovery rocked the archaeological world.

Of course, it would come under intense scrutiny. Bible detractors would not easily accept an artifact as authentic that bears the name of King David. Yet after much examination and questioning, retranslating and re-questioning, the Tel Dan Stele has been accepted as a genuine piece—after all, it had been discovered by genuine scientific excavation. And while it is the most certain of all references to King David, there are two other artifacts that, with near certainty, make similar mention of the king.

And numerous other artifacts have been discovered that have helped to greatly fill out the story of King David. Archaeology is not just turning up the odd token biblical name. Rather, the sum total of evidence today is filling out entire stories.

King David truly was a legendary king. This is the true story of that legend—as told by the Bible and confirmed by archaeology.

David’s Inscriptions

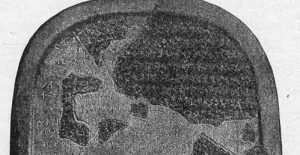

Alongside the Tel Dan Stele, we must mention the two other artifacts that make near-certain reference to King David. One is the Mesha Stele. This victory stone belonged to another man mentioned in the Bible—the Moabite King Mesha. This stone celebrated Moab’s rebellion against the king of Israel around the middle of the ninth century b.c.e. (2 Kings 3). Toward the base of the inscription, the same phrase used on the Tel Dan Stele can be found: “house of David.” Although, due to damage, the initial “D” is missing (i.e., BT[D]WD). According to epigrapher and philologist André Lemaire, who carefully studied the artifact, any reading other than “David” would be an awkward fit.

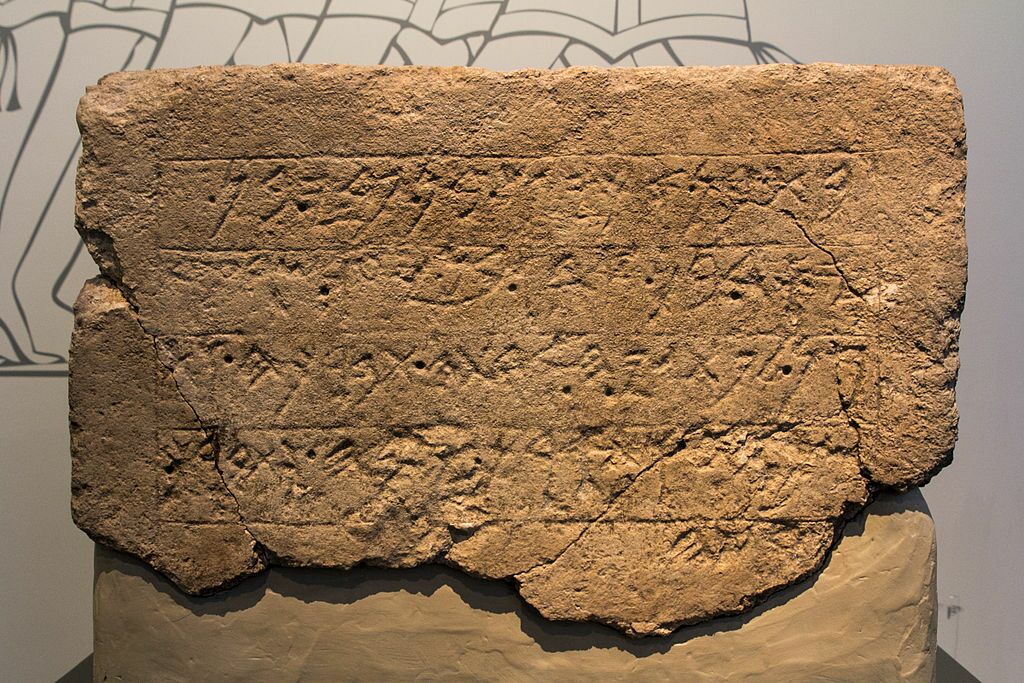

Then there is an Egyptian inscription dating to around the end of the 10th century b.c.e., which describes a part of Israel’s Negev desert region as the “Heights of David.” Leading Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen translated the Egyptian inscription as H[Y]DBT DWT. The first word indicates “heights,” or “highlands.” The second word presents more of a problem at first glance. The name “David” is properly written on the first two inscriptions as DWD. So what of DWT? Kitchen came across a sixth-century a.d. inscription from Ethiopia, which referred to David as Davit. Hence, for this general region, there is a precedent for the name DWT, Davit. As with the Mesha Stele, “David” seems to be the best-fitting translation. Naming this area of the Negev as the “Heights of David” also makes sense because it was in the area to which David fled and commanded while on the run from King Saul.

While the above two translations aren’t in themselves 100 percent sure references to King David, they certainly make for convincing accumulative evidence.

David: Humble Beginnings

David started out in life as a lowly shepherd, the youngest son of his father, Jesse. While at that time of no kingly heritage, David was certainly a brave and faithful young man. While tending to his father’s sheep, he fended off attacks on the livestock from both a lion and a bear (1 Samuel 17:34-36). The presence of such animals within Israel, mentioned a number of times in the Bible, might sound unusual. Yet bears still are known to live in the wider region (such as this recent sighting of a Syrian brown bear in Lebanon). This species of bear, which can grow up to 550 pounds, is no longer found in the wild in Israel. Also, the Asiatic lion species lived within the territory of Israel right up to the time of the Crusades, before it became extinct around 800 years ago. So such an attack against David’s flocks would not have been uncommon. What was uncommon was David’s fearlessness in single-handedly defending his flock. He was also somewhat of a “renaissance man”—his musical abilities were already well known in the area, as was his remarkable relationship with God (1 Samuel 16:18).

As he was tending sheep in the hilly terrain on the outskirts of Bethlehem (a town well known archaeologically to have been on the scene at this time), David was summoned back to his father’s house where the Prophet Samuel was waiting. Samuel, sent on a mission from God, immediately took his horn of oil and anointed David king over Israel.

David was now the God-ordained replacement to the failure that was King Saul. Yet it would be some time before the people of Israel came to recognize him as their new king.

Saul, Israel’s first king, had repeatedly rejected God’s instructions. He became depressed, irrational and even possessed. David—a recognized harpist—was called into the royal court to attempt to soothe the troubled Saul. By this point in history, the harp was a well-known instrument. Evidence of its use in the Middle East has been dated to more than 2,000 years before David. So by David’s time, the harp would have been a well-honed instrument. David’s music did wonders in calming Saul. He also became Saul’s armor-bearer. It seems that after some time, David was released from Saul’s employ. But he would soon meet the king again, due to a very large problem.

Philistine Problems

This problem, of course, was Goliath and the Philistines. The Philistines at this point in time (end of the 11th century b.c.e.) were causing problems for Israel. Archaeology has confirmed their powerful presence in the territory bordering Israel during this time period. At this point, Philistine armies had invaded Judah and gathered near the Valley of Elah. Not about to allow the Philistines free entry, Saul took the Israeli army and camped nearby, setting his troops on an opposing mountainside. At this point the giant champion of the Philistines, Goliath, began a daily march out in front of the Israelites, bellowing for a one-on-one confrontation to decide the fate of the two armies. His blasphemous tirades were constant and intimidating.

While no remains of the giant have been found, something can be said at least for his name. Goliath was from Gath. This city site has been identified, and within it was found two inscribed names on pottery (dating to the 10th century b.c.e.), bearing a similar linguistic link to Goliath—Alwat and Wlt. Of course, our Anglicized version of “Goliath” is much different from the original rendering—written in Hebrew as Galyat. These names all show Indo-European roots rather than Semitic roots like the Canaanite and Hebrew names. This makes sense, because the Philistines were originally of Mediterranean origin.

David, whose brothers were encamped against the Philistines, came to the Israelite camp to deliver supplies from their father. A fortress where the Israelites had likely stationed themselves has been found. Known today as Khirbet Qeiyafa, this circular fort has been dated to the time of Saul and David. It was located on one side of the Valley of Elah (as per verse 2), and had the rare feature of two city gates. 1 Samuel 17:52 describes a place in the area known as Shaaraim (meaning “two gates”). Further, the word “trench” used to describe the Israelite encampment (verse 20) can be translated as “circular rampart”—something very similar to the appearance of modern-day Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Seeing the Israelite men fearfully cowering from Goliath’s tirades, David marched up to King Saul and demanded to be allowed to go and fight this Philistine. Saul, initially hesitant, conceded. The heavily armed and armored Goliath thought the man approaching him—small, shepherd-like and virtually weaponless—was merely a joke. He taunted the young man, to which came the reply:

“You are coming against me with sword and spear and javelin. But I am coming against you in the name of the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel’s armies, whom you have defied!” (1 Samuel 17:45; New English Translation)

David launched a slingstone directly at the giant. The stone sunk into Goliath’s skull, killing him instantly. The sling had been quite a common (and surprisingly deadly) weapon for thousands of years before David’s time. When using optimal ammunition, a slingstone can travel faster than an arrow, with greater range, accuracy and impact. They can be fatal even when the victim is wearing armor. While the tool is often seen as the “poor man’s weapon,” David skillfully used it to great effect.

Seeing their champion dead, the Philistines fled from the battle. The Israelites quickly celebrated, upholding David as their champion and singing of how his exploits had topped those of King Saul. Naturally, this enraged Saul. He was beginning to realize that this man might be the one to take the kingdom from him. He began plotting to kill David, who was forced to go on the run for many years.

David the Fugitive

While on the run from Saul, David went to the Philistine city of Gath, intending to talk to King Achish and stay within the city. The inhabitants, however, recognized David for his exploits against the Philistine army. (Interestingly, at this point in time, even they referred to him as “king of the land”—1 Samuel 21:11.) Fearing execution, David feigned madness—he began drooling and clawing at the city gate—and the Philistines swiftly ejected him from Gath.

This chief Philistine city has been found and excavated by archaeologists. In excavations during the summer of 2016, a massive city wall and huge entry gate were discovered. According to the site’s director, the gate is one of the largest ever found in Israel’s region. David would certainly have been familiar with the gates of Gath—perhaps this was the very gate at which he clawed and drooled before getting booted out. Gath’s large proportions would certainly fit for a home of giants—the Bible describes at least five who lived within its walls (2 Samuel 21:15-22).

Gath’s King Achish later actually befriended David, who did go on to stay with the Philistines while on the run. He even gifted David a portion of his territory. At another Philistine city, Ekron, a genealogy inscription has been discovered, dating to the seventh century b.c.e. One of the kings on the list is of the same name, Achish. This provides confirmation for what would have been a familiar Philistine name; and like Goliath, Alwat and Wlt, the name is not Semitic.

Saul devoted much time to hunting down David. David moved from place to place—staying with the Philistines and frequenting the desert Negev region (and possibly inspiring the above Egyptian name “Heights of David”). Finally, the Philistines killed Saul and his sons in a successful battle against the Israelites (1 Samuel 31). They impaled the bodies of Saul and his sons on the city wall of Beth Shean. This city has been discovered by archaeological excavations and was proved to have been in use around this time period.

David, who honorably mourned his hunter’s death, was now recognized by his tribe of Judah as the new king. But the rest of Israel followed Saul’s son, Ishbosheth. This man was also known in the Bible as Ishbaal (1 Chronicles 8:33). The name Ishbaal, used 14 times in the Bible, has been discovered at the above-mentioned site of Khirbet Qeiyafa. A pottery rim was found decorated with the name “Ishbaal,” dating around the 11th to 10th centuries b.c.e. Interestingly, the Bible shows this kind of name featuring the term “Baal” was common around that time. After David’s time, however, these sorts of names fell out of use, probably due to their association with the pagan god Baal. This artifact helps prove that the Bible was not some document written long after the fact with made-up names. Rather, as Old Testament Prof. Claude Meriottini wrote, “this discovery serves to affirm that some of the biblical names were also common at the time these persons mentioned in the Bible lived.”

Ishbaal’s reign lasted only two years. A drawn-out war took place between the house of David and the house of Saul during that time. Those Jews who supported David gradually grew in strength and power, while the house of Saul began to fade to insignificance. Ishbaal was eventually murdered by two of his captains (2 Samuel 4:5-6). As a mark of justice, David executed his opponent’s murderers.

Israel, now leaderless (and probably admiring David for his just judgment toward the murderers who slew Ishbaal), joined Judah in throwing full support behind the king. David now was recognized as king of all Israel.

City of David

One of David’s first acts from this point was to establish his new capital city. He had previously reigned in Hebron. Archaeology has shown that this Hebron, centered on Tel Rumeida (located within modern-day Hebron), was one of the most important Judean cities. Based on excavations, archaeologists have dated the discovery of a significant building program at Hebron to around the time of David—perhaps while he was king reigning from that city. The time period has been called the “golden age at Hebron.”

Hebron was located deep within the territory of the tribe of Judah. A new capital would be needed to help bridge the divide between Judah and the rest of Israel. This would need to be a city located along a tribal boundary, with just the right attributes for a capital—a city like Jerusalem.

Jerusalem at that time was a smallish fortress established within the Judean hill country. It sat directly on the border between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin, necessarily helping to establish tribal unity. It had a constant and reliable water source—the Gihon Spring—and was well defensible as it was perched atop a mountainous ridge. In fact, so defensible was the city that the Canaanites who still inhabited it (of the Jebusite tribe, who had named the city Jebus), boasted to David that the “blind and lame” could sufficiently defend the city from him. Quite a boast to a king who had the full force of the united Israelite tribes behind him. Of course, David saw this as a challenge.

David’s nephew Joab led a group of men through a water conduit up into the city and overthrew it, subsequently settling himself into the position of captain over Israel’s army (2 Samuel 5:8; 1 Chronicles 11:5-7). The city then became known as the “City of David.”

During her 2008 excavations in the City of David, Dr. Eilat Mazar’s team stumbled upon a tunnel dating to this time period. The tunnel, still blocked by debris, is at least 160 feet long, cut through a natural crack in the bedrock, and walled up on both sides, barely allowing passage for a man to squeeze through. This tunnel, which may have originally been used to channel water, has been identified as a candidate for the conduit through which Joab and his men infiltrated and conquered Jebus.

And so Jerusalem became Israel’s capital city. Much additional construction was accomplished there by David, as told by the Bible and witnessed through archaeology at the site. One of the monumental constructions attributed to David is the giant Stepped-Stone Structure. This magnificent supporting structure was excavated and dated by Dr. Mazar to around the start of the 10th century b.c.e. This structure was built on the northeastern-most part of the original city of Jebus. It appears that the Jebusites could not expand their city further north up the mountain ridge due to a large gap in the bedrock. With the huge amount of national support and infrastructure available to David, however, the Stepped-Stone Structure was probably built to fill in this gap in the bedrock and allow the city of Jerusalem to further expand north.

The Stepped-Stone Structure was also vital for supporting a very significant building—the Large Stone Structure.

David’s Palace

If the term “Large Stone Structure” sounds a little mundane, its other title certainly isn’t: David’s palace. This structure, planted directly atop and beyond the Stepped-Stone Structure, dates to the 10th century b.c.e. and is enormous. The wall of this building was up to 10 feet wide and 100 feet long! Added to that, another 16-foot-wide wall was unearthed belonging to the structure.

Based on the archaeological evidence, as well as the scriptural record, Dr. Mazar has concluded that this must have been the palace of King David. It is the most impressive building on the site, for the time period. It was at the highest point of the city. Its pottery dates to the time of David—with pottery found beneath dating to just before his arrival. Certainly a large building project had begun in the city under David—and indeed, the Bible mentions that one of those large projects, supported by the king of Tyre, was the building of David’s palace! (2 Samuel 5:11).

Another piece of evidence Dr. Mazar used to identify this magnificent building as David’s palace was 2 Samuel 5:17: “[A]ll the Philistines came up to seek David; and David heard of it, and went down to the hold.” This verse shows that David had to have been dwelling somewhere high up atop the City of David—and this “Large Stone Structure” was right on the summit. During this threat from the Philistines, he went down into the lower parts of the city—more closely shielded by fortifications—where he could assemble his troops to attack.

As big as this palace was, only about 20 percent of it has thus far been excavated. Future excavations are in the planning stages.

Acts of David

King David, now established in Jerusalem, began to project his power throughout the kingdom of Israel. Yet he still met with much opposition. The Philistines continued repeatedly to hound David, and he continued to beat them back. One of his many successful battles was at Gezer (one of the cities in Ephraim’s jurisdiction) where the Philistines made a stand with the giant Sippai. Archaeological excavations have attested to a Philistine presence at Gezer.

One of David’s significant acts was bringing the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem. His first attempt was done contrary to the laws of moving such a sacred item—as a result, one of David’s men died. Later, David organized a proper transport of the ark in a glorious procession, successfully bringing it to the City of David. The discovery of this ark has remained elusive for thousands of years. This would surely be the single greatest artifact ever found. The Prophet Jeremiah wrote that the ark would no longer be “visited” after the coming of the Messiah—thus implying that it will be found and visited beforehand.

The transition of the ark and tabernacle to Jerusalem was one thing—but David had even greater goals.

“See now, I dwell in an house of cedar, but the ark of God dwelleth within curtains” (2 Samuel 7:2). David purposed to build a grand temple for God. However, God inspired the Prophet Nathan to tell David not to do so. He had been involved in too many bloody wars throughout his life to be allowed to build such a sacred building. Instead, his son Solomon would build it. And out of great love for David’s attitude and obedience, God promised to make David a house—an eternal covenant that his kingdom and lineage would be established on the throne forever, right into the reign of the Messiah who would also be of his lineage (2 Samuel 7).

David continued to subdue the belligerent Philistines, Moabites, Ammonites and Syrians. “And the Lord preserved David whithersoever he went. And David reigned over all Israel; and David executed judgment and justice unto all his people” (2 Samuel 8:14-15). David was cementing himself as Israel’s greatest king.

But something went tragically wrong.

David, Bathsheba and Consequences

While his men were out at war, King David stayed behind in Jerusalem. One night, while walking on his rooftop, he noticed a woman bathing below in the city. Remember, David’s palace was high up on the city-mount, and would have commanded a clear view of all of Jerusalem. Overcome with lust for the woman, David brought her into his house and committed adultery with her. This deed started a snowball effect of problems for the house of David.

David at first tried to hide his act, but the now-pregnant Bathsheba meant that was impossible. He organized the murder of her husband, Uriah, and took her as his wife. God sent the Prophet Nathan to rebuke David—and the king finally bitterly repented of his actions (see Psalm 50). God forgave him, but the curse that “the sword shall never depart from your house” remained.

A number of catastrophic events followed. David’s eldest son, Amnon, raped his half-sister. In revenge, David’s son Absalom killed Amnon. Absalom then began an effort to take over the throne of Israel from his father, forcing him and his loyal supporters to flee Jerusalem. Subsequently, a massive civil war broke out, causing the deaths of at least 20,000 people (including the usurper Absalom). David was able to return to Jerusalem and reinstate himself.

David made one more particularly fatal mistake—taking a forbidden national census of his troop numbers. Even David’s corrupt military leader Joab knew that this was forbidden and attempted to talk David out of it. But the king went ahead with the count, and as a result a great plague swept through Israel killing 70,000 people. Realizing his tragic mistake, David pleaded for God to take his own life in the place of his fellow citizens. Acting under instructions from the Prophet Gad, David set up an altar at the threshingfloor of Ornan the Jebusite. (Note: Archaeology has confirmed the name “Gad” to have been used during this time period.) The deeply repentant David offered up burnt offerings and peace offerings, and the plague was stopped.

David’s Last Years

David’s long reign, which he continued in humility and righteousness, was drawing to a close. His health was deteriorating. Yet there were still some key events to happen.

The threshingfloor on which David offered sacrifices, slightly further north up the mountainous ridge from his palace, would become the location for the future temple built by his son and successor, Solomon. While David wasn’t allowed to build the temple, he put all of his effort into collating the precious materials. He even put together the “blueprints” for the temple, as he was inspired by the Spirit of God (1 Chronicles 28:11-12). All Solomon would need to do was put the pieces together.

The temple location would become Israel’s holiest site. While the first and second temples were razed and rebuilt through the centuries, there can be no doubting their existence. Numerous archaeological finds and extra-biblical accounts confirm the biblical record of a temple situated a short walk north of the City of David.

David also divided and organized the priestly responsibilities for proper worship. 1 Chronicles 24 lists the men that he rallied. Various forms of the names of three of the priests (Jakim, Hezir and Maaziah) have been found in ancient inscriptions.

The sheer amount of valuables that David was able to gather for the building of the temple shows the immense scope and power of his kingdom. That powerful kingdom would be inherited and continued by his successor, Solomon. But Solomon’s rule was threatened even before it began. Another of David’s sons, Adonijah, attempted to insert himself as the next ruler over Israel. David caught wind of the plot and instantly ordered his son Solomon to be crowned king at the Gihon Spring. All Adonijah could do was throw himself at the mercy of Solomon (who later had Adonijah executed for another treasonous attempt at the throne). Solomon was now the undisputed ruler of all Israel.

The Legend of David

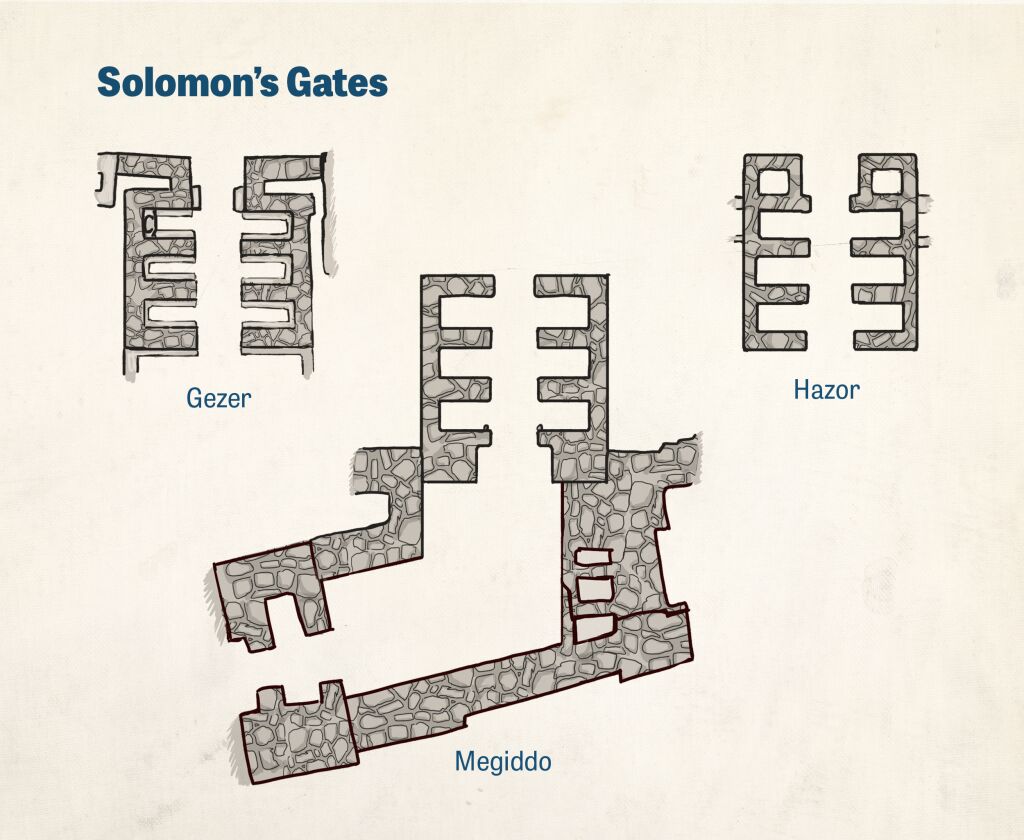

Thus a new king of Israel began his reign as David’s life ebbed away. Solomon inherited and expanded the already powerful kingdom of Israel. Archaeology continues to confirm the powerful nature of this kingdom at this time—one of the proofs of this being the remains of Solomon’s unique building program of standardized gates throughout Israelite cities. These are known as the six-chambered gates, with the most notable examples found in Gezer, Megiddo and Hazor (2 Kings 9:15). “Solomon’s Mines” continue to be excavated far south of Israel, within the territory of Edom. David had helped to accelerate the sheer power and spread of Israel’s might up into Solomon’s time. Thus it would be no surprise, with such a powerful kingdom built under David, for surrounding nations such as Egypt, Moab and Syria to reference the name “David” on their artifacts, such as the Negev Inscription, the Mesha Stele and the Tel Dan Stele.

Solomon’s reign began illustriously, with an already powerful kingdom. David’s reign, though, had started very differently. He couldn’t have come from a lower position—a lowly shepherd in the Bethlehemite hill country. He had to fight and struggle every step of the way to stand as king over Judah and eventually all Israel. He made some catastrophic mistakes along the way. But he was praised for his incredible repentance. Unusual for a powerful king, David was not afraid to admit that he was wrong. And he had a remarkable respect and love for God. A majority of the Psalms testify to this king’s great devotion to God and His laws. It is no wonder that God called David a “man after mine own heart.” Psalm 8:3-4 show a glimpse of David’s awe for God:

When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained; What is man, that thou art mindful of him? and the son of man, that thou visitest him?

David’s incredible history makes him the most legendary king ever to walk Earth.