When did the Exodus and Israelites’ entry into Canaan take place? That’s a contentious question—not to mention whether or not it did happen.

A general scholarly consensus puts an “Exodus” and Israelite establishment in Canaan during the 13th century (the 1200s) b.c.e., as the following examples show:

- “Exodus, the liberation of the people of Israel from slavery in Egypt in the 13th century b.c.e.” (Encyclopedia Britannica, “Exodus”).

- “C. 13th century, Exodus from Egypt” (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, “Facts About Israel”).

- “Moses (c. 1350-1250 b.c.), Hebrew prophet and lawgiver. Transformed a wandering people into a nation” (U.S. Capitol Relief portrait summary).

- “Most scholars … date this possible exodus group to the 13th century b.c.e. at the time of Ramses ii” (Wikipedia, “The Exodus”).

- “Semitic immigrant workers in Egypt … may have drifted back to Syria-Canaan in the 13th century for a variety of reasons” (National Geographic, “We May Now Know Which Egyptian Pharaoh Challenged Moses”).

- “This event, had it been true, is generally held to have taken place toward the end of the 13th century b.c.e.” (Psychology Today, “Why the Exodus Story Has Value Despite Being Complete Myth”).

In looking for evidence on the ground in Canaan from this 13th century b.c.e., however, archaeologists generally cite a dearth of evidence. As such, while a general consensus puts the setting of the biblical Exodus and entry chronologically within the 13th century, a general scholarly consensus is also that it did not happen—at least, nowhere near as the Bible describes.

- “[With] a lack of evidence for Joshua’s conquests in the 13th century b.c. and the indistinguishable nature of pottery, architecture, literary conventions and other cultural details between the Canaanites and the new settlers … the case for a literal reading of Exodus all but collapses” (Los Angeles Times, “Doubting the Story of Exodus”).

- “It’s just an autochthonous group at the end of the 13th century sitting there somewhere in the highlands [of Canaan]” (Haaretz, “For You Were (Not) Slaves In Egypt”).

- “The consensus of modern scholars is that the Bible does not give an accurate account of the origins of the Israelites” (Wikipedia, “The Exodus”).

- “The Exodus did not happen as written in the Bible during the 13th century” (Prof. Israel Finkelstein).

As archaeologists Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman write in their book The Bible Unearthed, “The conclusion—that Exodus did not happen at the time and in the manner described in the Bible—seems irrefutable … repeated excavations and surveys throughout the entire area have not provided even the slightest evidence.”

But did you know that the Bible does not state that the Exodus occurred in the 13th century b.c.e.? In fact, biblical chronology shows that the Exodus in no way could have happened during the 13th century. So should it be any surprise that the 13th-century finds on the ground do not match the biblical Exodus? (Such a lack of finds for this period, then, if anything only serves to corroborate the biblical account.) How can the Bible be condemned for something antithetical to what it says?

Let’s examine what the Bible says about when the Israelite Exodus and arrival in Canaan happened, why the 13th-century date came into vogue, and where any corroborative evidence lies.

What Bible Chronology Says

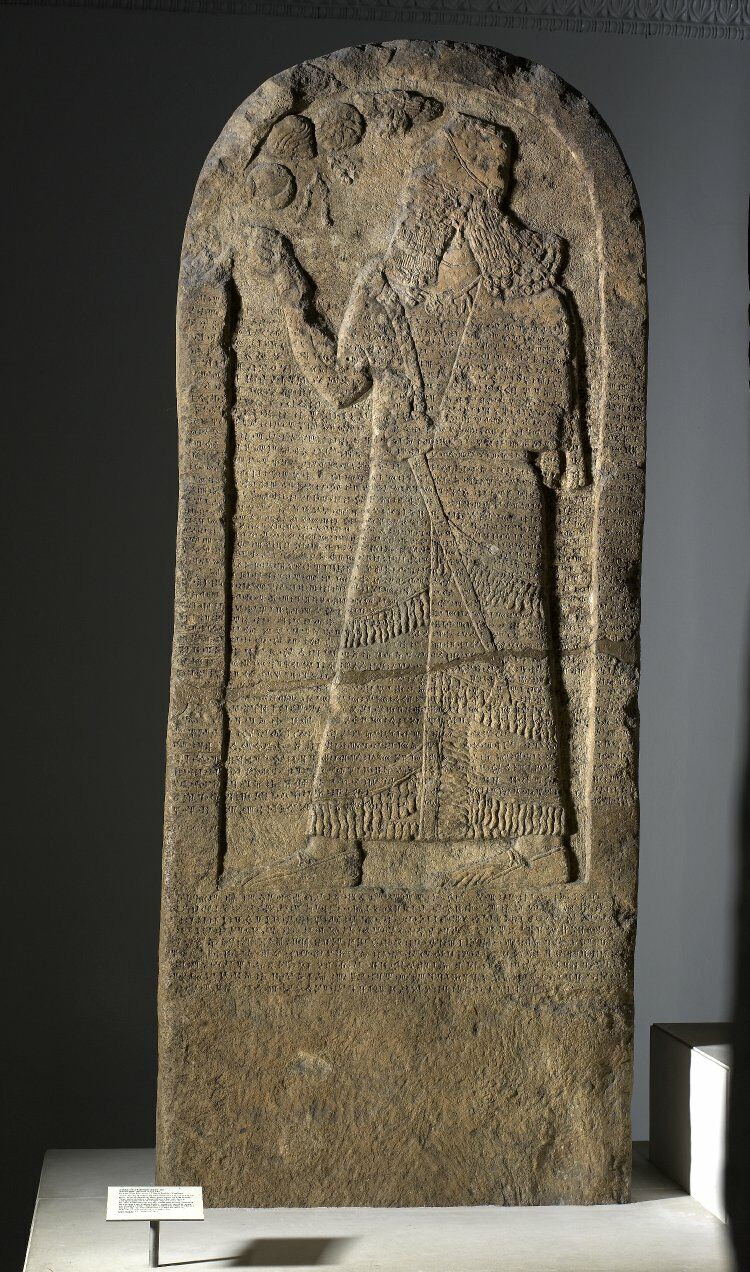

The period of the Israelite kings has been well established, pairing the detailed biblical chronological information with datable archaeological discoveries. Numerous foreign inscriptions mention contemporaneous kings. King Ahab, for example, is mentioned on the Kurkh Monolith in the context of the Battle of Qarqar (853 b.c.e.), linking his reign to several other regional rulers and chronologies. There is also the Black Obelisk, mentioning the tribute of King Jehu (841 b.c.e.).

Taking such information and extrapolating the biblical chronologies back gives us a good fix for the united monarchy of Israel under kings David and Solomon, universally recognized as relating to the 10th century b.c.e. More specifically, with Solomon’s reign beginning in 971 b.c.e. and his temple building commencing in 967 b.c.e. (2 Chronicles 3:2). This date of 967 b.c.e. is the widely recognized date for the construction of the temple, and has been refined right down to the nearest year, not only by ancient artifacts and biblical chronologies, but also independently of both—using the remarkably agreeing data preserved by historians of classical antiquity (based variously on how the temple date relates to their records of the establishment of Rome, Carthage, Tyre, and the fall of Troy). You can read more about how this date for the temple’s construction was arrived at here.

And that date of 967 b.c.e. is critical to this discussion. 1 Kings 6:1 reads: “And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of Israel were come out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month Ziv, which is the second month, that he began to build the house of the Lord.” From here, it is simple math: 480 years earlier than 967 b.c.e. brings us to an Exodus date of circa 1447–1446 b.c.e. Subtract the 40 years of sojourn in the wilderness (i.e., Joshua 5:6), and that brings us to an entry into Canaan around 1407–1406 b.c.e.

That’s nowhere near the 13th century. That’s two centuries earlier, within the 15th century b.c.e.

1 Kings 6:1 is pretty black-and-white. And so some, naturally, have wondered if the author of this passage was simply mistaken, or if this scripture was merely meant as a non-literal, symbolic, generational number (this theory is addressed in the following article). Besides the peculiarity of this suggestion: Is there any other internal biblical evidence, for or against?

One of the later biblical “judges” on the scene, before the monarchical period, was Jephthah (Judges 11-12). Based on the internal dates in the book of Judges, he would have been on the scene about a century before David, around 1100 b.c.e. During his time as judge, a territorial dispute with the Ammonites arose over land that Israel had conquered just before Moses’s death. Jephthah questioned the timing of the Ammonite king’s desire to reclaim the land: “While Israel dwelt in [this area] by the side of the Arnon, three hundred years; wherefore did ye not recover [it] within that time?” (Judges 11:26). Israel, to that point, had already been in the land roughly 300 years.

Again, the math is simple: 300 years before 1100 b.c.e. gives an entry-into-the-Promised-Land date of about 1400 b.c.e. Forty years of sojourning earlier brings us to the Exodus. This puts Solomon and Jephthah in precise agreement: The biblical Exodus took place in the middle-15th century b.c.e., with the entry into the Promised Land at the end of that century.

Additional Internal Evidence

There are numerous other biblical details that point to the same chronological outcome.

Adding up the internal dates in Judges for the periods of oppression followed by periods of peace equals, at face value, very roughly 400 years (Judges 3:8, 11, 14, 30; 4:3; 5:31; 6:1; 8:28; 9:22; 10:2-3, 8; 12:7, 9, 11, 14; 13:1; 16:31). The math isn’t that simple—there would have been some degree of overlap of certain circumstances and events (and the following article contains additional detail relating to this point). Still, the general span of events consistently points to a long judges period of around 400 years before the monarchical period.

This same refrain is mentioned in the New Testament by Saul (later called Paul)—a man originally educated as a devout Pharisee (Philippians 3:4-6). In one of his first speeches, he summarizes the history of ancient Israel: “And after that he gave unto them judges about the space of four hundred and fifty years …” (Acts 13:20). There is some debate surrounding the translation of this passage; nevertheless, the rounded timeframe is a good fit, when including the first “judge” of Israel, Moses (i.e. Exodus 18:13), through Samuel. The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus, a contemporary of Paul, also allots a similarly long judges period.

Evidence is also in the form of genealogies. 1 Chronicles 6:18-22, for example, details 19 generations from the time of the Exodus to the time of David (verses 33-37 in other translations). If the Exodus really was in the 13th century, then depending on the starting point within that century, that would mean each new generation (in the case of 1 Chronicles 6, each sanctified, Levitical generation) was conceived within the early-mid teens (and that as an average—and assuming a best-case scenario, of all as firstborns!). The genealogies work out perfectly, however, for a 15th-century Exodus—around 25 years old for the father of each successive generation.

This is just a sampling of the more obvious and straightforward, internal biblical evidence for a much earlier, 15th century b.c.e. Exodus. There are others besides (such as the rather more complex, yet remarkable calculation of Jubilee years and land sabbaths). In sum, Bible chronology clearly and consistently reveals that the Exodus could in no way have happened in the 13th century b.c.e. So where did this date come from? Why is it touted as the period of the biblical Exodus (and at the same time used as evidence against the Bible)?

Ramesses-es and Destructions

Given this internal textual evidence, the foundation for a 13th-century Exodus has to be that the Bible is an inherently flawed, contradicting and unreliable text—hence the necessary dismissal of the above chronological material. (This includes reasoning that the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 is simply a symbolic, non-literal number; that Jephthah’s “three hundred years” were the unreliable ramblings of a “blubbering idiot”; and that the genealogies of 1 Chronicles 6 were the product of some sort of artificial extension.)

From this starting point, then, 13th-century proponents point in particular to the store cities that the Israelites built while slaves in Egypt, “Pithom and Raamses” (Exodus 1:11). “Rameses” is also used in a few other Exodus verses as a geographical marker (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:3, 5).

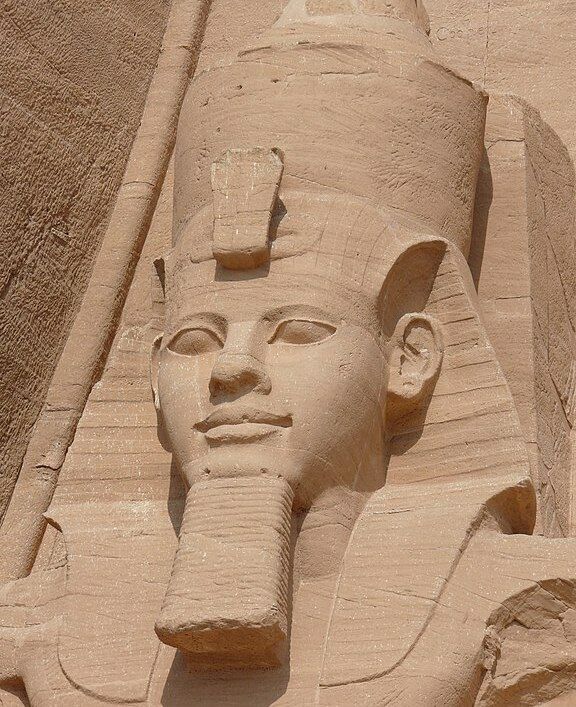

Pharaohs named Ramesses came on the scene beginning the 13th century b.c.e. (i and ii), on into the 12th (iii). As such, the great Ramesses ii (1279–1213 b.c.e.), one of the greatest pharaohs of Egyptian history, is often identified as the pharaoh of the Exodus. His new capital, “Pi-Ramesses,” is typically identified as the one built by these Israelites. (The even later 12th-century Ramesses iii is also sometimes offered as an alternative pharaoh for the Exodus.) Thus, the biblical account is often regarded as a somewhat hazy, late “remembrance” of enslavement under the rule of this great “builder”-pharaoh.

To go along with this, certain 13th-century b.c.e. destruction layers have been found around Canaan, thus presented as a link to an “Israelite” conquest (keep in mind that more typically in scholarship, the Israelites are simply regarded as another Canaanite faction rising up and overthrowing their fellow Canaanites, and that there was no substantial Israelite journey out of Egypt). We also start to see somewhat of a material change in the archaeological remains from this 13th century onward, in the lead-up to the later monarchical period.

Hence, what is presented as limited “evidence” of a 13th-century “Exodus”/conquest, yet certainly not in terms of the grandeur of the biblical account.

Is there any logical biblical answer to these allegations? Is the Bible in conflict with the external evidence?

Anachronisms

First, let’s take a look at a key point, the place name “Rameses.”

An anachronism is a later, typically better-known name given to something from an earlier, lesser-known time period. It is used quite frequently in history books, ancient and modern. For example, Julius Caesar conquering France; Gaul was its name at the time, but the anachronism “France” conveys more meaning to a modern audience.

The Bible contains many anachronisms, based on when the various books were compiled and also edited. For example, Abraham and his men are described chasing Mesopotamian armies northward to “Dan” (Genesis 14:14). This territory was named after Abraham’s great-grandson, some 400 years later during the time of the judges (Judges 18:29). The reason for the anachronistic use is clear in the Bible: “Dan” is one of the most frequently-used border terms, used to describe the northernmost bounds of Israel’s territory (with Beersheba on the opposing, southernmost end; e.g. Judges 20:1; 1 Samuel 3:20; 2 Samuel 24:15; 1 Kings 5:5; 2 Chronicles 30:5). Thus, for the later Israelite population to understand just how far north the patriarch Abraham went, the anachronistic term “Dan” was used. Other examples of anachronism include, for example, Bethel (Genesis 12:8, 28:19); Asshur/Assyria (Genesis 2:14, 10:11, 22); and Amalek (Genesis 14:7, 36:12).

What about the location name Rameses? When weighed against these other above-mentioned, consistent chronological scriptural references, the case can easily be made that this geographical name was likewise being used in the Bible anachronistically.

But beyond that: Bible precedent reveals that the place-name Rameses clearly was being used as an anachronistic term. That’s because the same name was also used in the story of Jacob. As far back as Genesis 47:11—centuries before the Exodus and long before the Israelite slavery began, let alone the building of Rameses itself—we find the geographical term “Rameses” used. Does this mean, then, that the patriarchs Jacob and Joseph must likewise be squeezed into the 13th (or even 12th) century b.c.e.? Of course not. The biblical use of “Rameses” is anachronistic. (This subject is discussed in much more detail in our article “The ‘Raamses’ of Exodus 1:11: Timestamp of Authorship? Or Anachronism?”)

This conclusion—that the “Raamses” of Exodus 1:11, for example, must have been a later name used to describe an earlier, lesser-known location—actually accords with the testimony of our earliest Egyptian record of the Exodus, that of the third century b.c.e. historian Manetho. He associates our Israelites repeatedly with the earlier city Avaris (as relayed throughout much of Josephus’s Against Apion, Book 1). Ramesses ii later constructed his capital Pi-Ramesses on the northern end of this territory of Avaris, near the site of the former, original city.

And as for the name and identity of the Exodus pharaoh: There has been endless speculation on this subject, with dozens of different Egyptian pharaohs proposed by many dozens more researchers, as candidates for the figure behind the Exodus. Actually, there is quite a good historical reason for why he is not specifically named in the biblical account (see here for more detail). Nevertheless, the Egyptian historian Manetho identifies him as a pharaoh named Amenhotep. Pharaohs with this name ruled Egypt from the late-16th to the mid-14th centuries b.c.e.—again, fitting squarely with the biblical timeframe of a 15th-century Exodus. (For a detailed examination of this question about the identity of the Exodus pharaoh, see our article “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?”)

Destructions and Assumptions

What about the certain 13th-century city destructions around the Holy Land—and an apparent lack thereof during the earlier 15th century? Does this provide evidence of a 13th-century invasion of Canaan, following the Exodus?

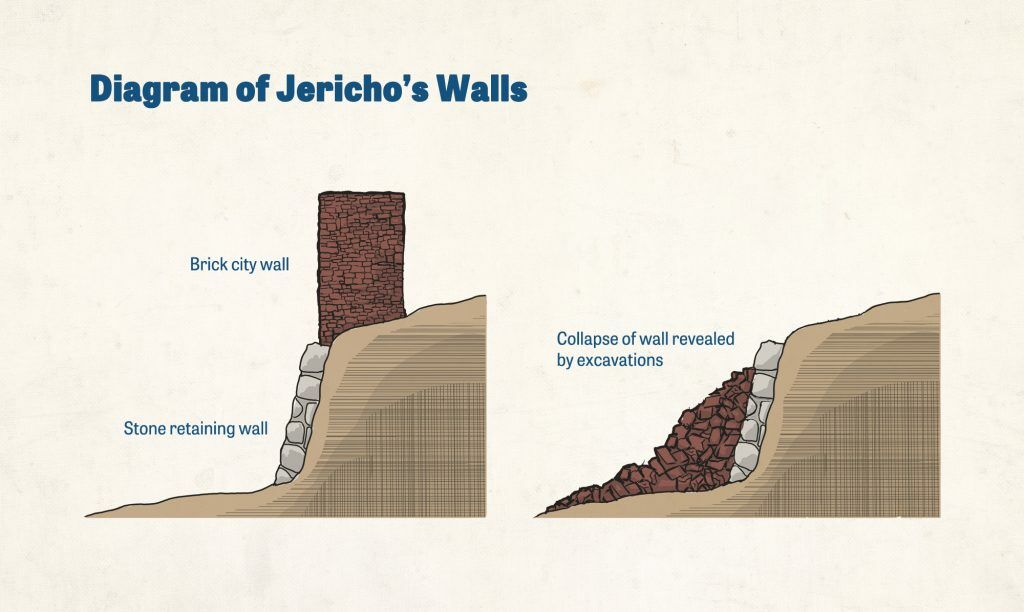

There are a lot of assumptions about how the invasion of Canaan took place. Many appear to be false. Did you know that the biblical invasion of Canaan was not a city-by-city destruction? In fact, the Bible specifies just three fortified cities as being reduced to ashes by the Israelites (Jericho, Ai and Hazor—more on this further down). The Bible actually takes pains to mention the preservation of Canaanite city structures, as opposed to destroying them. Joshua 11:13: “But as for the cities that stood on their mounds, Israel burned none of them, save Hazor only” (this, following the destruction of Jericho and Ai). Instead, the Bible describes numerous staged land battles with the Canaanites. City destructions are a good fit with the later, bloody Judges time period.

Besides this, what about the general lack of definitive evidence of cultural change to a new population—change in dwellings, pottery, etc—something that did not start to become more noticeable until the 13th century and beyond? The Bible itself preemptively states that this would be the case.

Deuteronomy 6 reveals that the Israelites would simply move into existing Canaanite cities (again, rather than destroying them), and would continue to use their equipment and work their fields: “[T]o give thee—great and goodly cities, which thou didst not build, and houses full of all good things, which thou didst not fill, and cisterns hewn out, which thou didst not hew, vineyards and olive-trees, which thou didst not plant …” (verses 10-11).

Further, the Bible reveals that the Israelites failed to drive out a bulk of the Canaanite population, and even turned to Canaanite paganism themselves (Judges 1-3). Judges 5—according to internal biblical chronology—is set around the 13th century b.c.e. The “Song of Deborah” contained within this chapter laments the earlier state of poverty that Israel as a nation was in up to that point: “[T]he highways ceased, And the travellers walked through byways. The rulers ceased in Israel, they ceased …. They chose new gods; Then was war in the gates; Was there a shield or spear seen Among forty thousand in Israel?” (verses 6-8). But then note what occurred during that century—the 13th century b.c.e.: “Awake, awake … Awake, awake … Arise … lead thy captivity captive …. Then made He a remnant [other translations read Israelite survivors] to have dominion over the nobles and the people [oppressing Canaanites, at the time of Deborah] …” (verses 12-13). The passage proceeds to show the rise of Israel as a larger body out of obscurity and Canaanite oppression—during the 13th century b.c.e.!

Additional External Evidence

But can anything more indicative be said for an entrance of the Israelites into the land of Canaan at the close of the 15th century, on into the 14th?

As mentioned above, three cities are named as being destroyed at the time of the conquest: Jericho, Ai and Hazor. The exact location of Ai is still debated—although some fascinating evidence, including a circa 1400 b.c.e. destruction layer, has been found at the proposed site of Khirbet el-Maqatir. A 13th century b.c.e. destruction layer has been found at Hazor, and is often held up by late-date proponents as evidence of the conquest at that time. Yet evidence has also been found of a 15th century destruction at the site. (Further, the 13th century destruction remains fit well with a certain event during the period of the judges.) Still, the above two cities of themselves give us no firm, conclusive resolution for either side of the debate.

The famous biblical site of Jericho (where the walls “came tumbling down”), however, is an entirely different story. The site has been conclusively identified and excavated—and there is no late-date, 13th-century destruction material for this city, nor destruction material anywhere close to this time period. Yet there is dramatic parallel evidence for this destruction described in the Bible—firmly and only in the general timeframe of an early Exodus.

Tel Jericho was initially excavated by British archaeologist John Garstang, whose efforts during the 1930s confirmed to him that a significant destruction of Jericho had occurred around 1400 b.c.e. The city site was excavated again during the 1950s by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon, who dated the collapsed-outer-wall destruction layer somewhat earlier—roughly 1550 b.c.e. Her dating is slightly earlier than the 15th-century biblical chronology. But whether or not one adheres to her or Garstang’s interpretation, both are clearly within the general timeframe of the earlier biblical Exodus chronology. (And in the realm of 3,500 years, in Kenyon’s limited excavation using 1950s techniques to arrive at a Bronze Age dating based primarily on what was not found—150 years is virtually synonymous. Furthermore, archaeological evidence since presented points again back to Garstang’s initial conclusion—a destruction date of around 1400 b.c.e.)

But cities to one side, as stated above, the conquest at this time (circa 1400 b.c.e., on into the 14th century) was primarily in the form of land battles and territorial seizures. And while a “lack of physical evidence” is often cited as evidence against an Israelite conquest, this is somewhat misleading because there is an abundance of textual evidence.

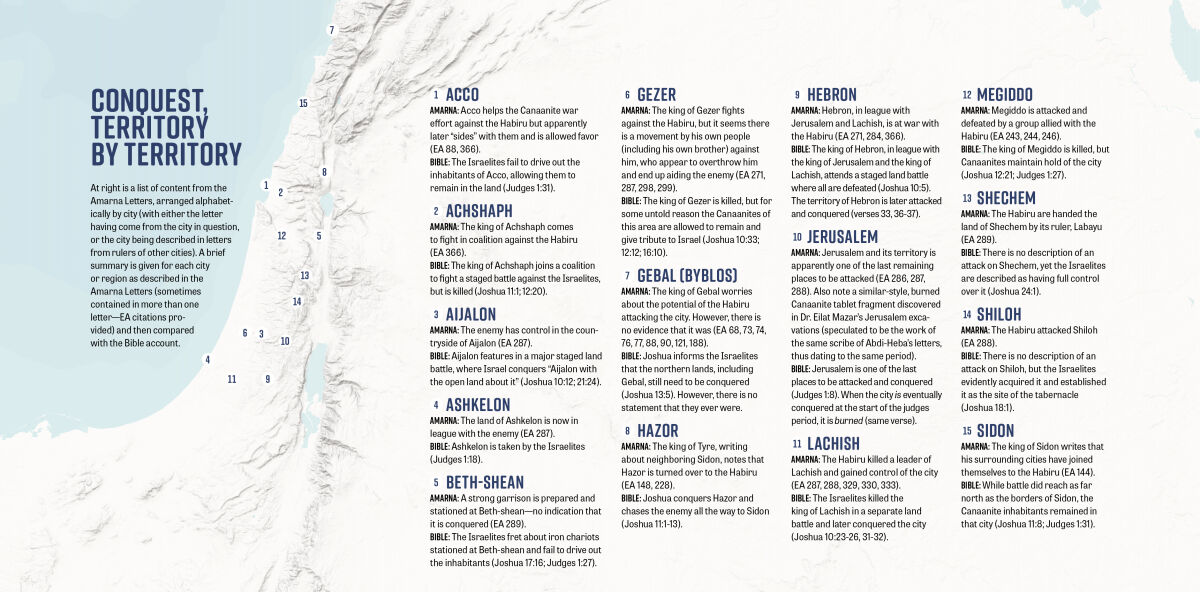

The Amarna Letters are a trove of Canaanite documents dating to the early-mid-14th century b.c.e., uncovered in the Egyptian city of Amarna. The cuneiform tablets were sent from leaders (“mayors”) throughout Canaan to the pharaoh (who largely controlled Canaan at the time). Many of the letters are written in a tone of sheer desperation for military aid, describing the entire land being overrun by an invading people named the Habiru. Here are some examples:

- “May the king [pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted …. Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord. The king has no lands. The Habiru have plundered all the lands of the king. If there are archers this year, the lands of the king, my lord, will remain” (EA 286, a letter from the king, or “mayor” of Jerusalem).

- “Since the Habiru are stronger than we, may the king, my lord, give me his help, and may the king, my lord, get me away from the Habiru lest the Habiru destroy us” (EA 299, a letter from the king of Gezer).

- “Lost are the territories of the king. Do you not hear to me? All the rulers are lost; the king, my lord, does not have a single ruler left …. The Habiru sack the territories of the king … if there are no archers, the territories of the king, my lord, will be lost!” (EA 288, again from Jerusalem).

The name Habiru naturally brings to mind the biblical name Hebrew. (At this point in the Bible story, in naming the identity of the populace, Hebrew is used more often than Israelite.) Note the emphasis, again, on widespread conquered territory—“all the lands of the king.” This subject of the identity of the Habiru as the biblical Hebrews, and the Amarna Letters as referencing the Israelite conquest of Canaan, is covered in detail in our article “The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?” Suffice it to say that the Amarna Letters dramatically parallel the biblical chronology and account in numerous respects. (Below is a city-by-city map comparing the biblical account of the invasion with the content of the Amarna letters.)

The list of evidence for the establishment of Israel in the land at the end of the 15th century through the first half of the 14th century could go on. There is the 13th-century Merneptah Stele, which directly mentions Israel as an already well-established entity in the land by that point. There is the Berlin Pedestal, for which dating is contested, but which appears to reference the presence of Israel in the land perhaps during the 14th century b.c.e., or even as early as the 15th century (click on the links for more information).

There is the Soleb Inscription of Pharaoh Amenhotep iii (whose reign spanned the late 15th to early 14th centuries b.c.e.), referencing a nomadic people “of Yahweh”—this is the earliest-known inscription bearing the name of Israel’s God, Yahweh, and is in the context of territory somewhere east of Egypt. This is especially significant, given that prior to God’s instruction to Moses, this name Yahweh was “not known” to the Israelites or their forefathers (Exodus 6:2-3)—nor to Egypt’s pharaoh (5:2). This acknowledgment of “the Name” on this pharaonic inscription therefore tidily fits with a 16th-15th century Moses and a mid-15th century Exodus having already occurred—but requires explaining away, in order to fit with an Exodus several centuries later.

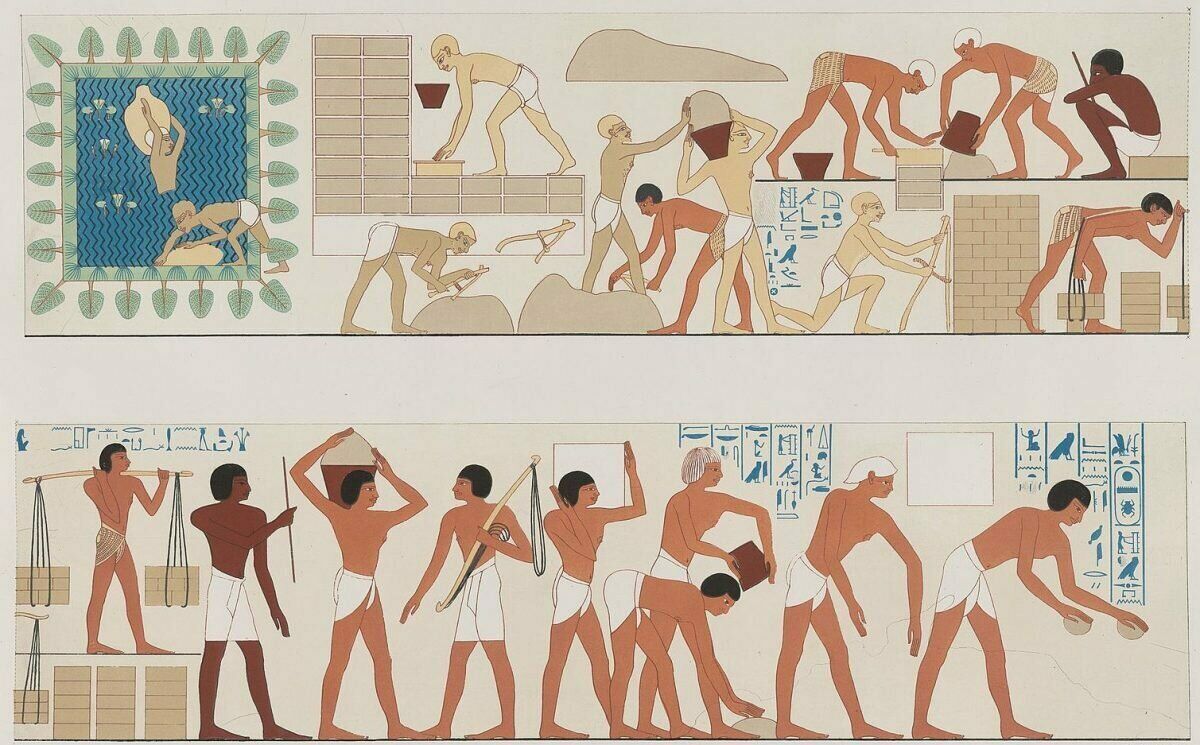

There is also perhaps the most dramatic snapshot of Israelite “slavery” in Egypt, of the brick-making sort described in Exodus 5, in the tomb art of the Egyptian noble Rekhmire (below). This depiction shows eastern, Semitic slaves making bricks in the very same manner described in the Exodus 5 oppression, just before they were freed from Egypt. What is the dating for this tomb art? Around the middle of the 15th century b.c.e. (And inscriptions from Rekhmire’s tomb also fit well with the Exodus 1:11 account of the building of the pharaoh’s treasure cities—see here for more detail.)

Points could further be made relating to the early part of the judges period, following Israel’s initial establishment in the land. One in particular is Israel’s first oppression by the kingdom of Aram-Naharaim (Mitanni, as described in Judges 3). This was a powerful kingdom on the scene during the early 14th century b.c.e., synonymous with biblical chronology, but one that had already ceased to exist following the supposedly late-13th-century Exodus and conquest.

Then there is the external evidence for the early date of the Exodus from Egypt itself—as tied to the 16th-century b.c.e. Egyptian oppression and overthrow of its Semitic Hyksos population, and their expulsion thereafter east from the land. Josephus directly identifies these people as the Israelites, translating their Hyksos title as “shepherd kings.” The Egyptian historian Manetho describes these Hyksos as having, following their departure from Egypt, “built a city in that country which is now called Judea … and called it Jerusalem” (as quoted in Josephus’s Against Apion, 1.14). More about the Hyksos, and related Egyptian evidence for the Exodus itself, can be found in our articles “The Hyksos: Evidence of Jacob’s Family in Ancient Egypt?” and “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?” And again, as with the internal biblical points for an early Exodus date, the list of outside evidence from archaeology and classical history could go on.

Of Biases and Existential Battles

The Wikipedia page for “The Exodus” (certainly not the most reliable of sources, but inevitably and unfortunately the page which will get the most views) sums up the Exodus, conquest and chronology as follows: “There are two main positions on the historicity of the Exodus in modern scholarship. The majority position is that the biblical Exodus narrative has some historical basis, although there is little of historical worth in the biblical narrative. The other position, which has seen increasing scholarly support, is that the biblical exodus traditions are the invention of the exilic and post-exilic Jewish community, with little to no historical basis.”

Two rather dismal options: The Bible account is slightly true (but of no real worth)—or is entirely untrue. Take your pick.

Is that fair, though? As we have covered, relating to the dating of Israel’s emergence following the Exodus, it most certainly is not. Of course, much still remains to be found relating to the Israelite Exodus and appearance in Canaan. But as the saying goes, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” (After all, the contemporary biblical Hittite kingdom was once scoffed at as entirely fictional—until it was discovered in the early 20th century as one of the most powerful empires in ancient history. Forget wandering Israelite nomads, how do you lose an entire empire?) But what has been found relating to the Israelite Exodus and conquest remarkably attests to the biblical account—one of an Exodus during the mid-15th century b.c.e. and a conquest of Canaan at the end of that century. This despite a widespread bias toward entirely the wrong period.

As for “bias,” none of this should be new, or surprising, to the Jewish people. Israel’s existence has always been a fight; so too, the history of its existence.

Read More:

Jericho, Ai, Hazor: Investigating the Three Cities ‘That Did Joshua Burn’

The ‘480 Years’ of 1 Kings 6:1: Just a Symbolic Number?

Jephthah’s ‘Three Hundred Years’: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The 19 Generations of 1 Chronicles 6: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The ‘Raamses’ of Exodus 1:11: Timestamp of Authorship? Or Anachronism?

The Tribe of Asher in the Exodus Date Debate

The Book of Judges Fails to Mention an Egyptian Presence in Canaan—Or Does It?

Manetho’s Exodus Pharaoh, ‘Amenophis’ (Amenhotep): Any Reason to Doubt?

Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?

Shiloh Sacrifices: Canaanite Or Israelite?

Amenhotep II as Exodus Pharaoh—With a Low Egyptian Chronology?