The biblical judges period is infamous for its violence and upheaval. Well-known accounts include Samson and the Philistines. Gideon’s 300. Samuel and Eli. The graphic assassination of the rotund Moabite king Eglon. Ruth and Boaz. The near-genocide of the tribe of Benjamin. A repeated cycle of foreign invasion, enslavement and oppression.

But one of the least known accounts of the judges is the very first oppression of all: the eight-year Israelite enslavement to Chushan-Rishathaim of Aram-Naharaim and his eventual defeat at the hand of the judge Othniel.

The historicity of the judges period is often dismissed as myth. Yet a growing amount of archaeological evidence attests to the accuracy of the accounts. In this third article in our Judges series, we go back to the beginning of the book and examine the evidence for this short—yet fascinating—account.

Historical Context

This story of oppression and freedom is contained within only four verses. The general scene, however, is set up by describing Israel’s immediate slump into idolatry upon settling in the Promised land. Judges 3:5-7:

And the children of Israel dwelt among the Canaanites, the Hittites, and the Amorites, and the Perizzites, and the Hivites, and the Jebusites; and they took their daughters to be their wives, and gave their own daughters to their sons, and served their gods. And the children of Israel did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, and forgot the Lord their God, and served the Baalim and the Ashteroth.

By following internal biblical chronology, this event occurs within the 14th century b.c.e. And archaeological discoveries, especially inscriptions, have revealed several of the entities in question—and general religious practices—during this period.

Around the 14th century, the Canaanite Amarna letters reveal a widespread invasion of “all the lands” by a people known as the Habiru (a group whose name, deeds and time period closely match the biblical Hebrews). The Berlin Pedestal also points to the name “Israel” as a known territorial entity around this time. The Canaanites, Hittites, Jebusites and Amorites are all entities around this same time period, known from various archaeological discoveries (see our article here for specific information on each). And thanks especially to inscriptions discovered in the northern Syrian city of Ugarit, we also have a fairly detailed picture of the type of idolatry and hedonism surrounding Baal worship. (Think temple prostitution, incest, drunken orgies and related evidence for bestiality and child sacrifice; see our article here for detail.)

This, then, is the cultural melee into which the early early-14th century Israelites sidled. Verse 8:

Therefore the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel, and he gave them over into the hand of Chushan-rishathaim king of Aram-naharaim; and the children of Israel served Chushan-rishathaim eight years.

Chushan-Risha-Who?

Enter one of the most peculiarly named individuals of the Bible: Chushan-Rishathaim of Aram-Naharaim.

First, let’s look at the nationality in question. “Mesopotamia” is the translation used in many English Bibles, but the original Hebrew, Aram-Naharaim, is a better representation that allows us to identify the power in question during this period.

Aram, of course, is well-known as referring to the northern territory of the Arameans—Aram, or alternatively, Syria. The name Naharaim literally means “two rivers”—hence the association with Mesopotamia (having the Tigris and Euphrates rivers). And on the scene at this precise window of time was a major Syrian–Aramean–Mesopotamian power of this very name. The Egyptians referred to it as Naharin (the equivalent of the Hebrew name). The Canaanites referred to them (in the 14th-century Amarna letters) as Nahrima. Today, they are better known as the kingdom of Mitanni.

Territorially, Mitanni, during its heyday, was one of the greatest powers in the Middle East. Yet little evidence has been discovered of Mitannite records—most of our knowledge of this empire comes from surrounding powers.

Mitanni, or Naharin, came on the scene around 1600 b.c.e. The seat of power for this kingdom was, as the Bible reveals, in the territory of Aram, northern Mesopotamia. By the start of the 14th century, Mitanni was at its height—and known for exerting dominance over the Levant during this century. This fits remarkably well with the Judges 3 description of Levantine oppression and domination by this northern power.

The geopolitical picture fits even further: Not only was Mitanni at its height of conquest and dominance during this period, but the empire collapsed completely that same century!

A ‘Lion of God’

Before we get to Mitanni’s demise, we return to Judges 3:9 to set the scene:

And when the children of Israel cried unto the Lord, the Lord raised up a saviour to the children of Israel, who saved them, even Othniel the son of Kenaz, Caleb’s younger brother.

Othniel means “lion of God.” We are first introduced to this “lionlike” character much earlier, in the book of Joshua. Joshua 15 describes the famous Israelite spy Caleb challenging any Israelite to conquer the city Kirjath-sepher (possibly a city of giants—verse 14) in return for his daughter Achsah’s hand in marriage. Othniel subsequently conquered the city (see also Judges 1 for a parallel account).

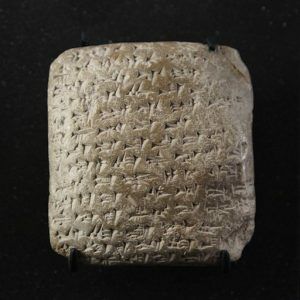

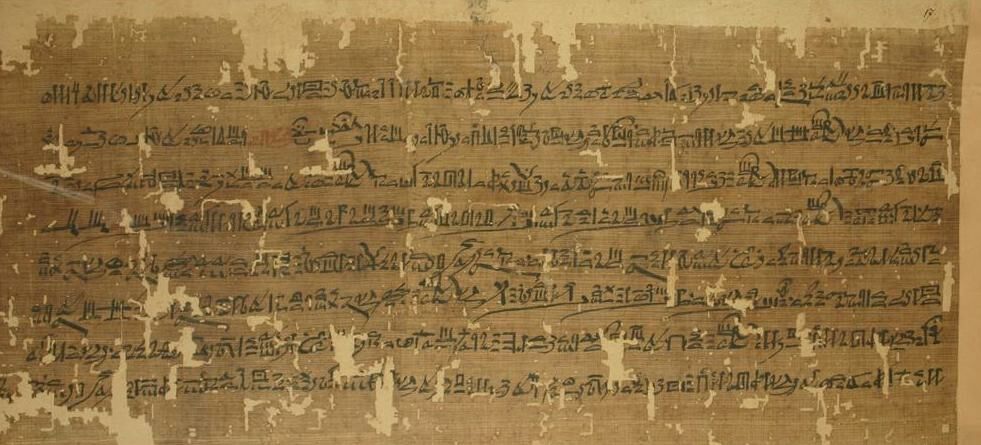

Othniel has not been confirmed by any inscriptions (more on this further down). But his city, Kirjath-sepher, is referenced by an ancient Egyptian papyrus, called Anastasi i. The papyrus dates roughly 150 years after the period in question (around the 13th to 12th centuries b.c.e.). Today, Kirjath-sepher is identified with the modern site Khirbet Rabud. And the name of Othniel’s father-in-law, Caleb, has been found on some of the earliest-known ostraca (inked pottery inscriptions), dating to the general judges period (note especially the Gezer ostraca, as well as one from Tel Arad). This, if not attesting to the biblical individual himself, at least affirms the biblical use of the name during the right time period.

Othniel’s exploits at Kirjath-sepher evidently established him as a man God could use as Israel’s “first judge”—a man who could lead Israel out of Mitannite oppression.

The Demise of Mitanni

And the spirit of the Lord came upon him [Othniel], and he judged Israel; and went out to war, and the Lord delivered Chushan-rishathaim king of Aram into his hand; and his hand prevailed against Chushan-rishathaim (Judges 3:10).

Othniel and his men would have gone up against the advanced Mitannite military equipment that made them famous—scale armor and spoke-wheeled chariots (both of which are arguably Mitannite inventions, and both of which would be used for thousands of years to come). Miraculously, as the Bible relates, the Israelites were victorious. “And the land had rest forty years”—as long as Othniel was alive (verse 11).

Again, what is fascinating about this account is that right at this time—immediately following the height of the kingdom of Mitanni—the 350-year-old kingdom utterly collapses. Why? According to historians, the answer is convoluted—various skirmishes and battles with neighboring regional powers such as the Hittites and Assyrians converged during this century, causing the kingdom to implode and cede its territorial dominions. Eventually, the Assyrians would move into the Mesopotamian void as the dominant power.

This historical picture fits incredibly well with the biblical one of the same century: an early regional Israelite resistance pushing back at the Naharaim dominion at the time of the Mitannite collapse. Perhaps Othniel’s resistance was one of the first dominoes to fall for the Mitannite empire.

A ‘Twice-Wicked’ King

The exact identity of Chushan-Rishathaim is unclear. There may be good reason for that. The name “Chushan-Rishathaim” in Hebrew means “twice wicked Chushan”; perhaps it is a manipulated pun by the writer based on a similar-sounding original name. Nonetheless, the name “Chushan-Rishathaim” is similar to several Mitannite kings of the same century: Tushratta, Artashumara, Shuttarna.

Further, the name Rishathaim is a good general fit with the name of northern Mesopotamian territory controlled by Mitanni—Reshet/Reshu in the Egyptian texts; Rishim/Urshu in the Ugaritic; Urshu in the Hittite; Urshu in the Eblaite.

There is one particular incident of note: Artashumara is a mysterious 14th-century Mitannite leader of whom little is known. He apparently ruled very briefly before he was killed by an obscure individual variously transliterated as Tuhi, Udhi and Uthi. Could this have been our Othniel/Uthniel (a longer variant of the Hebrew name Uthni)?

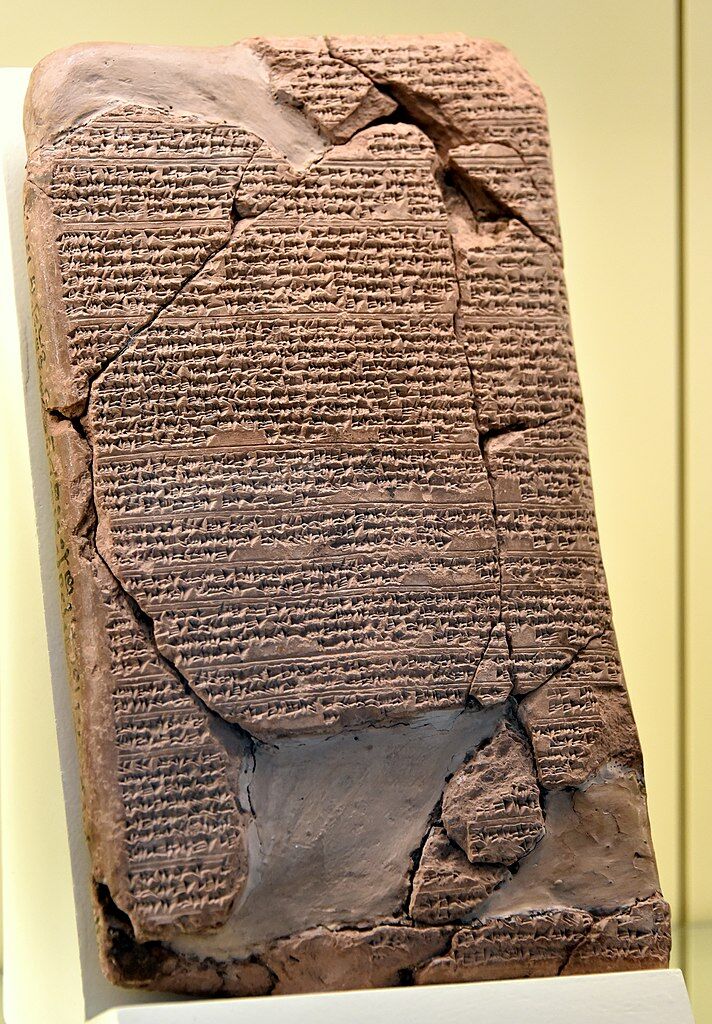

EA17

Artashumara is named on two Amarna letters, each written by his “brother” and successor Tushratta. One of the letters, EA18, is almost impossible to read due to damage—although a fragment of Artashumara’s name can be seen. The other, EA17, is more complete. It follows (emphasis added):

When I [Tushratta] sat upon my father’s throne, I was still young, and Uthi did evil to my land, and he killed his lord. And therefore he did not treat me well, nor he who was on friendly terms with me. I, however, because of those evils which were perpetrated on my land, made no delay; but the murderers of Artashumara, my brother, along with all that they had, I killed.

Virtually nothing is known about Artashumara. Historians can only speculate as to whether or not he was a true Mitannite king, a usurper, or even if he was a real “brother” to Tushratta, or simply a friend in the same sense of the word.

Still, there is enough information here to allow a little speculation. Tushratta was the son of the great Mitannite king Shuttarna ii, under whom Mitanni reached its height. (It was under the reign of Tushratta that the empire collapsed.) In his above letter, Tushratta gives us a clue of succession. He says that he “was still young” when he sat upon his father’s throne. Perhaps, then, his brother Artashumara—not in line for the throne (perhaps the offspring of a lesser royal wife)—stepped in as co-regent, adviser and general during Tushratta’s earliest years. After all, according to the letter, Artashumara is referred to only as a “lord”—and evidently a lord with jurisdiction over the territory related to Uthi.

Ultimately, the letter describes that though still young, Tushratta was king at the time that Uthi killed lord Artashumara and “did evil to the land” that the king lay claim to. Could this Tushratta, then, be one and the same Chushan-Rishathaim? The names are actually quite a close match. Tushratta is likewise a two-part name—Tush and Ratta—matching uncannily with the Hebrew root elements Cush and Rasha (again, the Hebrew “Rasha,” meaning “wicked,” is likely a wordplay related to the original name).

Further: The dates make sense. Tushratta’s reign began in the first half of the 14th century b.c.e., which fits. An eight-year oppression, up to the death of the lord Artashumara, would also fit tidily with a short co-regency period for this leader, while the king was still a child. And as for the “peace” Israel had for 40 following years, this matches the rough length of Tushratta’s impotent reign (exact dates still unknown). The focus of the major surrounding regional powers was concentrated around Mitanni at this time. An Egyptian inscription also matches the ensuing biblical account for Israel (more on this at the end of the article).

As for Tushratta’s reprisals on the murderers of Artashumara, the letter does not mention the death of Uthi himself. It may even be that Tushratta was lying to save face—after all, his letter was addressed to Egypt’s pharaoh Amenhotep iii, a friend of his father’s, in an attempt to win his favor and allay any of the pharaoh’s fears of instability.

Until more discoveries are made, we can only speculate based on fragmentary information. Still, Amarna Letter EA17, the killing of Artashumara by Uthi, Tushratta’s calamitous reign following the kingdom’s height under his father—it all fits the biblical account superbly.

The Exodus Connection

There is one final, important point to cover in the story of Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim. It is a tangential one, yet for our archaeological understanding today, perhaps even more important than the story itself. It is how the story fits with the Exodus.

When it comes to dating the Exodus, there are two main camps: One matches these events up with the late-15th century b.c.e.—this theory is based solely on the Bible and biblical chronology. The second, minimalist theory (favored by many archaeologists), takes a 13th-to-12th-century position—a late Israelite “arrival” in Canaan (if the Exodus happened at all). This theory is based largely on destruction material discovered and dated in cities throughout the region, a beginning change in material culture, and an admittedly selective reading of the Bible.

Yet none of the hard evidence discovered thus far negates the biblical 15th-century Exodus. In fact, it only supports it—and the account of Othniel and Chushan-Rishathaim is a case in point. Because if the Exodus and Israelite arrival did take place 200 years later, this would completely miss the Mitanni window—the powerful kingdom having already crumbled. As archaeologist Steven Collins writes in The Harvest Handbook of Bible Lands, “[A] remarkable historical synchronism arises from the book of Judges, linking a Mittani king in Judges 3:7-11 to a brief window of time toward the end of the Amarna period in Egypt ….” He continues:

By the end of the 14th century b.c.e., the Mittani kingdom and its Hurrian ruling class was all but extinct. … Chushan as a king of Aram Naharaim (Egyptian, Naharin or Nakh(ri)ma’ = “Mittani”) does not fit a post-1300 b.c.e. date for the exodus.

Likewise, an Amarna-period Mitannite oppression fits with the Amarna-period Habiru and their conquest of the land of Canaan. After all, this Mitannite oppression was the first—during, or directly following, this conquest period.

Thus, not only does Judges 3 fit with the archaeological evidence, this same archaeological evidence itself refutes a later 13th-to-12th-century Exodus claimed to be “based on archaeological evidence.” (In fact, the destruction sites held up as “proof” of a late-date Exodus do not fit with the biblical account—but do fit with the earlier Exodus period—read here for more detail.)

The historical context of Israel’s “first oppression” adds to a growing burden of evidence pointing to the biblical dating of the Exodus—and only a biblical dating—as one that fits the historical parameters. (The movie Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus—see the trailer below—does a good job of analyzing the two approaches to the dating of the Exodus.)

The Body of Evidence

Archaeology has not yet proved the existence of the individual characters in the story of Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim themselves (though it comes close). But the wider biblical account fits remarkably with the evidence from the historical period.

- Evidence for the 14th-century b.c.e. existence of the Hebrews, the Amorites, the Hittites, the Canaanites and the Jebusites

- Evidence for a hedonistic cult of Baal worship throughout the Levant

- The use of the Semitic name “Caleb” in an early, Judges-era context

- The early existence of Othniel’s city, Kirjath-sepher

- The Mitannite aggressor, at the height of colonial power beginning the century in question

- Evidence for Mitannite control over the Levant during this same period

- Matching Mitannite territorial and personal names

- The utter collapse of Mitanni during the same century.

The period of the Israelite kings, from around 1000 to 586 b.c.e., is well attested to in archaeology. We also now have quite a thorough emerging body of evidence for the Israelite judges: a bloody period in Israel’s earliest history, intended to highlight the pitfalls of relativism and following one’s own moral compass. As the book concludes and summarizes in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

As for Israel at the time of Othniel’s victory:

Israel would settle into 40 years of peace.

“And Othniel the son of Kenaz died” (Judges 3:11).

“And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord strengthened Eglon the king of Moab against Israel …” (verse 12).

Cycle: Repeat.

And some 40-odd years after the murder of Artashumara by Uthi, a late-14th century b.c.e. Egyptian scribe records the formation of a Moabite/Jordanian tribal coalition against the land of the Hebrews.

Articles in This Series:

Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Shamgar v. the Philistines: Evidence for the Biblical Account