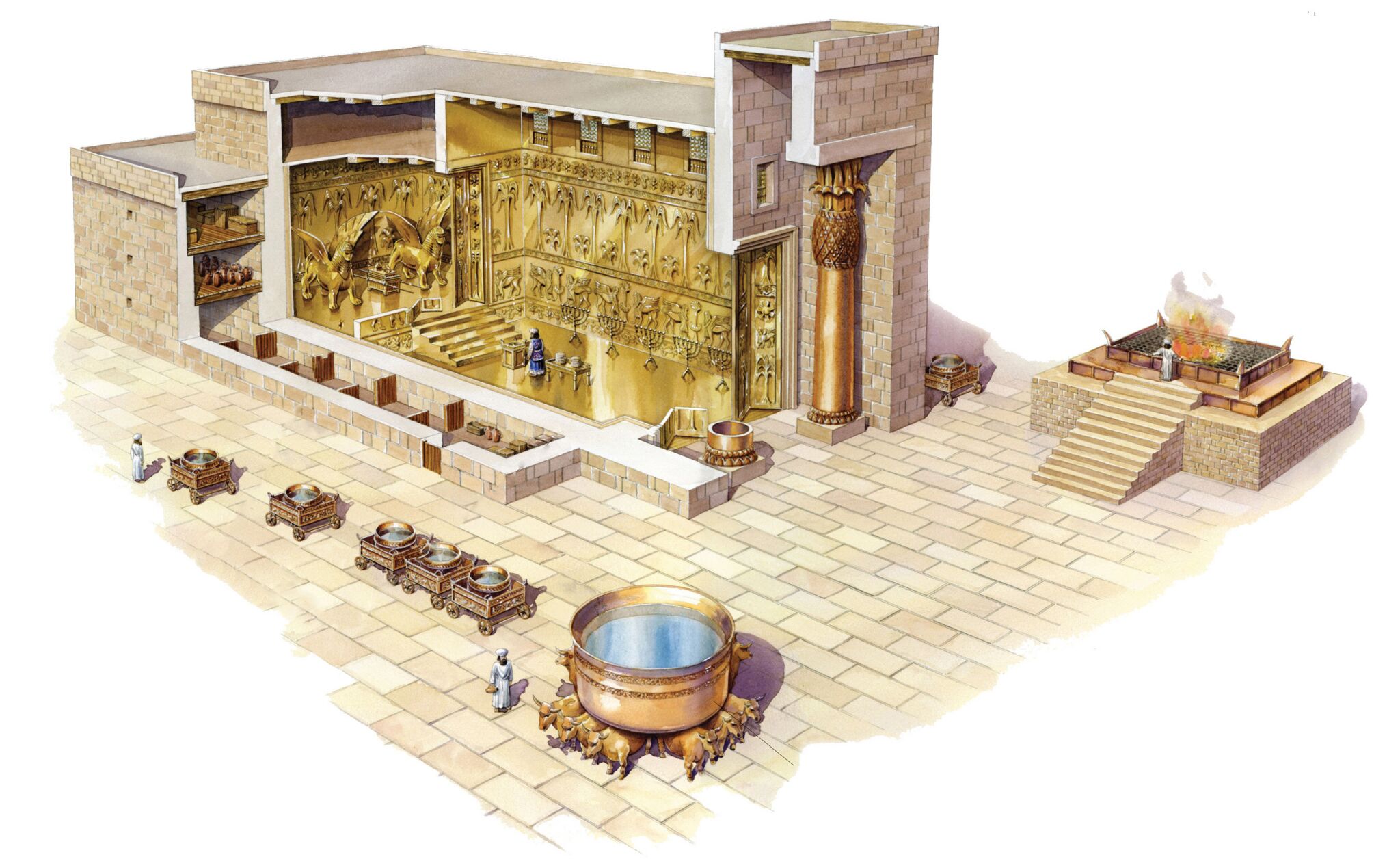

The year Solomon’s temple began to be constructed might seem like a rather random biblical date to be able to pinpoint specifically. Yet it is one of the lynchpin dates in the Hebrew Bible. It is the primary anchor given from which the Exodus can be dated (480 years earlier—see 1 Kings 6:1). In turn, this enables the dating of the period of the Israelite’s sojourn in the wilderness and entry into Canaan (Joshua 5:6), the establishment of the Israelite people in the land, and the start of the Judges period.

The widespread use of the date 967 b.c.e. for the building of Solomon’s temple might also sound peculiar—not least because remains of the temple have yet to be excavated. How was this date arrived at—and with what level of surety? There’s a rather fascinating story behind this, involving a missionary to China and a Belgian priest.

Using solely internal biblical chronology to date the reigns of David and Solomon—and, by implication, the building of the temple—is nearly impossible. It is not a matter of simply adding the lengths of reigns consecutively: There were several co-regencies between certain kings and their sons, and there are also evident differences in the way the reigns of kings in the northern kingdom of Israel were counted versus the reigns of kings in the southern kingdom of Judah.

Despite this, when it comes to this early date of the construction of Solomon’s temple, there is a significant majority agreement. In fact, it’s even more agreed upon than the dating of several later biblical kings and events. Why the strong consensus for 967 b.c.e.?

What is especially unique about the 967 b.c.e. date is that it has been established entirely independently, through several different methods and chronological directions.

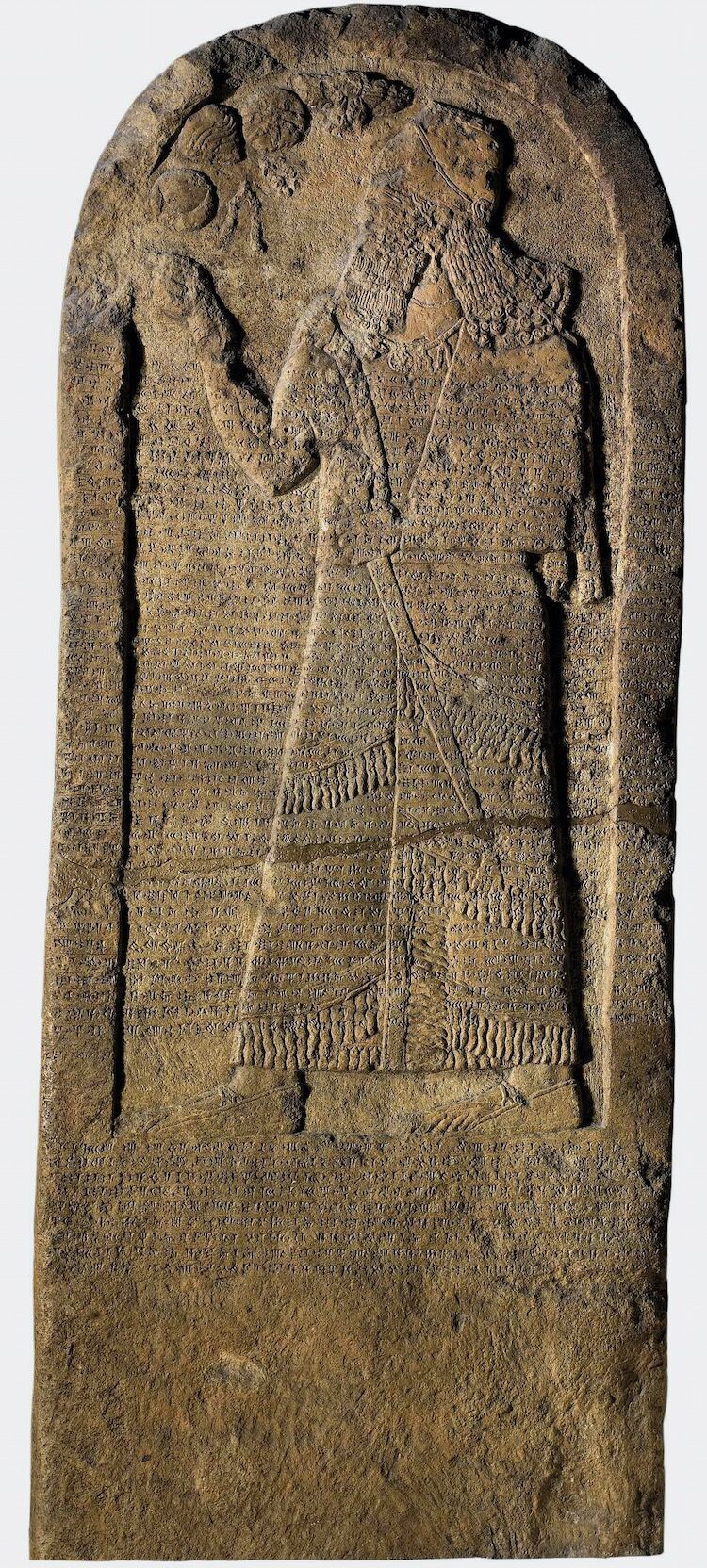

A typical method of determining the dating of biblical kings and events is combining archaeological information with the biblical. For example, several Israelite and Judean kings are mentioned on Assyrian artifacts from set periods (e.g. Ahab on the Kurkh Monolith at the time of the 853 b.c.e. Battle of Qarqar; Jehu on the Black Obelisk, paying tribute in 841 b.c.e.). Combining this information with a correct interpretation and synthesis of the chronologies in the biblical books of Kings and Chronicles enables the construction of a highly accurate chronology of biblical kings and events. It can also reveal exactly how the different chronologies of the polities of Israel and Judah were counted.

This was the method used by Edwin Thiele (1895–1986), an archaeologist and Seventh-Day Adventist missionary in China, whose biblical chronology is arguably the most widely respected. In the words of Assyriologist D. J. Wiseman, “The chronology most widely accepted today is one based on the meticulous study by Thiele.” Thiele established that certain apparent contradictions in chronology were simply the result of two different, yet equally accurate, biblical methods of regnal counting: an “accession year” method and a “non-accession year” method. Further, he determined that the “new year” for calculating regnal dates began in the spring for the northern kingdom of Israel (who used a non-accession year method) and in the autumn for the southern kingdom of Judah (who used an accession year method).

A particular key to this understanding were the discoveries of the above-mentioned Kurkh Monolith, the Black Obelisk and the Kurba’il Statue. These artifacts belonged to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser iii, and bore inscriptions relating to set dates in his reign. These monuments show that the reigns of Ahab and Jehu were separated by only 12 years, during Shalmaneser’s rule—Ahab mentioned as part of the Battle of Qarqar in “year six” of the Assyrian king’s reign, and Jehu mentioned as giving tribute in Shalmaneser’s “eighteenth regnal year.”

A face-value calculation of biblical numbers, however, would seem indicate that these kings were 14 years apart. This is because the king that followed Ahab, Ahaziah, is credited with a two-year reign (1 Kings 22:51), and his successor, Jehoram, is credited with a 12-year reign (2 Kings 3:1)—following which Jehu took the throne.

This seeming contradiction was resolved—and in fact, became “key” for the resolving of other otherwise difficult chronological issues—by Thiele’s discovery that the kingdom of Israel must have been using a non-accession year method of counting reigns. This method counts the first, partial calendar year of a king’s reign as his first year. Thus, Ahaziah reigned only one full year (and part of the year that Ahab died), and Jehoram eleven full years (and part of the year that Ahaziah died). This, then, gives 12 years between the reigns of Ahab and Jehu—resulting in precise agreement between the biblical text and archaeological record. (As for the Assyrian dates, in large part, they are fairly simple to follow. Besides the fact that we are in this case referring to one polity, Assyria, rather than two—Israel and Judah—Assyrian chronology was recorded on a detailed, albeit rather tedious, progressive year-by-year basis. Known as “Limmu Lists,” these chronological records included not only regnal information, but also a significant event that happened in each respective year of the empire. Among these are astronomical observations—i.e., eclipses—from which modern astronomers can derive pinpoint dates.)

Working backward from Ahab using these archaeological clues, with the addition of internal biblical information, Thiele was able to apply these regnal counting methods to trace back to the reign of Solomon. If Ahab’s final year of his reign was indeed the same year as the astronomically-anchored Battle of Qarqar in 853 b.c.e., then the start of his reign over Israel 22 years earlier could be aligned with the 38th year of Judean King Asa using the accessional calculations (1 Kings 16:29). This put the start of Asa’s reign at 911 b.c.e. Adding together the reigns of Asa’s predecessors—Abijam (a three-year reign), Rehoboam (a 17-year reign) and Solomon (a 40-year reign)—the first year of Solomon’s reign can be traced back to 971 b.c.e. The temple construction began in Solomon’s fourth year (1 Kings 6:1)—thus, 967 b.c.e.

But there is yet another, entirely different way to arrive at this date of circa 967 b.c.e.—providing further corroboration for its accuracy. This method was, in fact, arrived at before Thiele’s research—and at the time of his publication, Thiele was completely unaware of it. This was a method used by the Belgian scholar and priest, Valerious Couke (1888–1951).

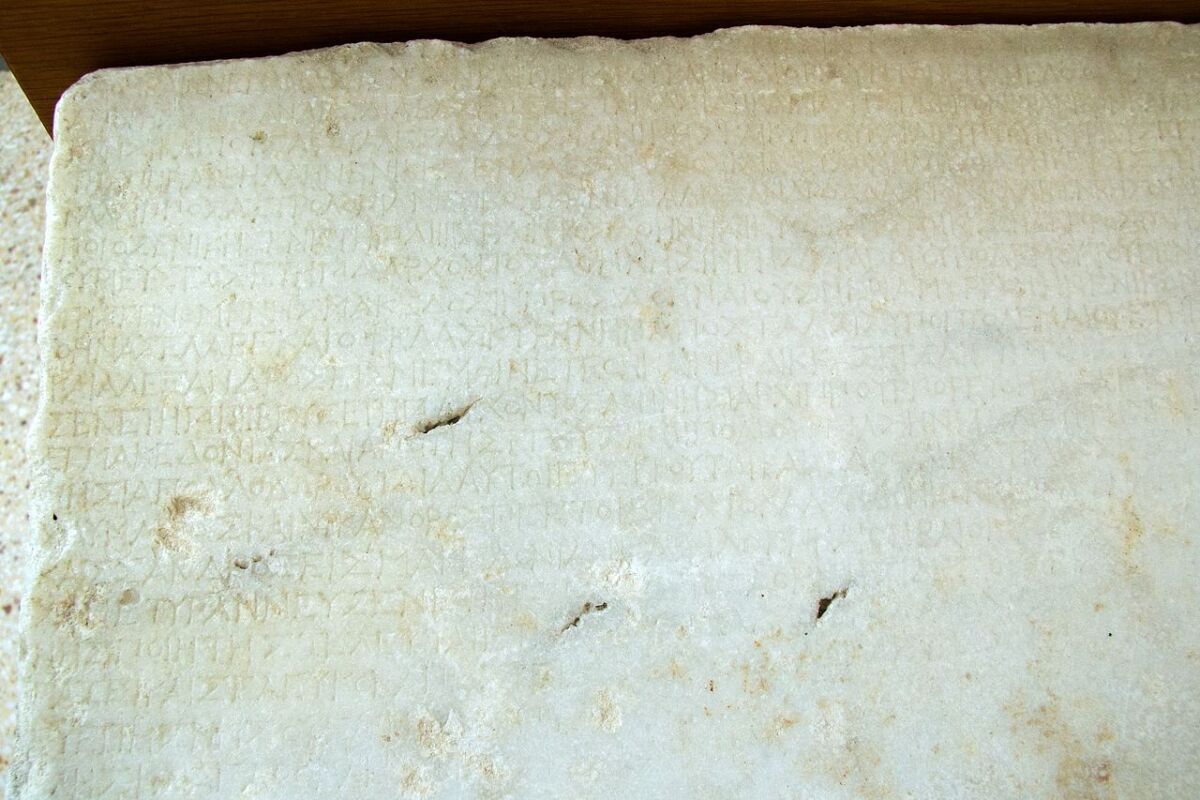

Coucke’s unique method was to deliberately set aside both the biblical and contemporary archaeological information and see if he could date the event strictly by using information from classical historians.

One of Coucke’s sources was the third-century b.c.e. Greek Parian Chronicle, which states that the city of Troy fell “945 years” before the installation of the chronicle—putting the fall of the city at circa 1208 b.c.e. Coucke then noted the first-century historian Pompeius, who wrote that the Phoenician city of Tyre was founded one year before Troy’s fall. Next, he turned to Josephus, who stated that King Hiram began to help Solomon with the building of the temple in the 241st year after the founding of Tyre (Antiquities 8.3.1; Against Apion 1.18), which provided a date for temple-building of circa 968 b.c.e.

Coucke then double-checked this by working backward, again through the chronologies of classical historians. He noted the record of the Tyrian King List, preserved through Josephus and Menander, from which Josephus repeatedly mentions that 143 years transpired from the time of Hiram’s assistance at Solomon’s temple to the founding of the Phoenician city of Carthage. Pompeius stated that the founding of Carthage was 72 years before the founding of Rome, which Roman classical historians set at 753/752 b.c.e. Thus, Carthage’s founding was in 825/824 b.c.e., placing the start of construction on the temple in 968/967 b.c.e.

Beyond that, Coucke noted the Bible’s peculiar use of Phoenician month names in the account of the temple’s construction, concluding that Solomon and Hiram used the same Tishri-based calendar in this effort. Based on this, Coucke concluded that Solomon’s fourth year as king began in Tishri 968 b.c.e. and that the temple was started in the following spring of 967 b.c.e. (1 Kings 6:1).

Naturally, the discovery of the little-known Coucke’s work was a boon to Thiele’s research. Only two publications from Coucke are known; a reignited search for more of his research at the Grootseminarie library in Belgium (from which he worked) failed to turn up any further material.

Of course, in the field of scientific research, conclusions are subject to change and face constant refinement. Such may be the case in the future regarding the lynchpin date for the construction of Solomon’s temple. But the current research and date of 967 b.c.e. represent the result of scientific analysis at its best: the same conclusion arrived at, from several directions, sources and methods, by researchers entirely unaware of each other.

And a conclusion, no less, that is central to determining the biblical chronology of all prior, pre-monarchical periods—right back to the Exodus and beyond.