In making the case for the early Exodus in the 15th century b.c.e.—as opposed to the comparatively popular late-date, 13th-century b.c.e. theory (or even later)—two biblical passages take center stage. One is 1 Kings 6:1, which states that “four hundred and eighty years” elapsed from the time of the Exodus to the building of Solomon’s temple (circa 967 b.c.e.). The other is Judges 11:26, which states that “three hundred years” had passed from the time of the conquest to the time of the judge Jephthah (circa 1100 b.c.e.).

1 Kings 6:1 is typically addressed by late-date proponents as representing merely symbolic, non-literal numerology; Jephthah’s speech in Judges 11:26 is sometimes dismissed rather more crassly as the ramblings of a “blubbering idiot.” In previous articles, we have addressed both of these subjects as they relate to anchoring the date of the biblical Exodus.

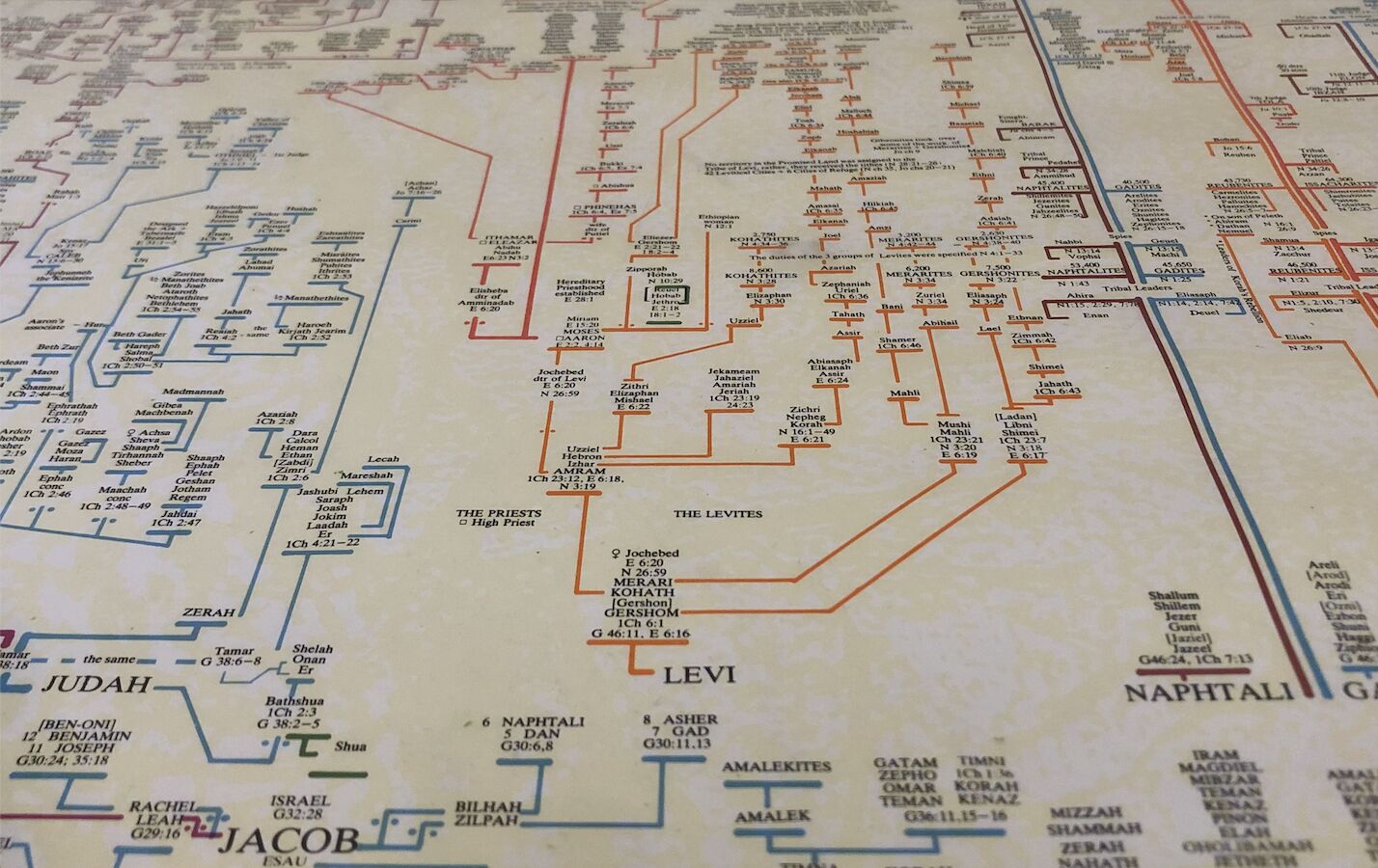

There is yet a third biblical passage commonly appealed to in making the case for an early Exodus date: This is a generational list found in 1 Chronicles 6, outlining 19 generations from the time of the Exodus to the time of David and Solomon. Yet here again, it is an argument for which there are late-date rebuttals. How do the arguments stack up?

19 Generations

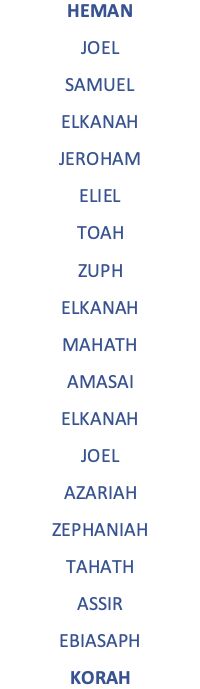

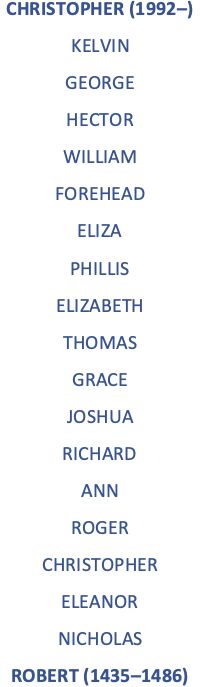

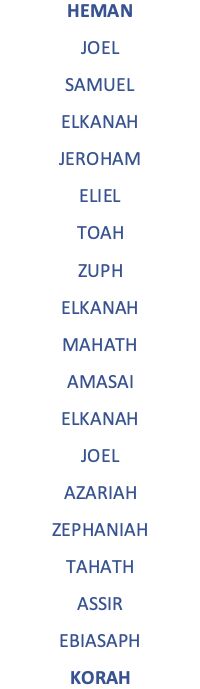

1 Chronicles 6 gives the genealogy of “Heman the singer,” whom “David set over the service of song” (verses 16-23 in the Jewish Publication Society translation; verses 31-43 in other translations). “Of the sons of the Kohathites: [1] Heman the singer, the son of [2] Joel, the son of [3] Samuel; the son of [4] Elkanah, the son of [5] Jeroham, the son of [6] Eliel, the son of [7] Toah; the son of [8] Zuph, the son of [9] Elkanah, the son of [10] Mahath, the son of [11] Amasai; the son of [12] Elkanah, the son of [13] Joel, the son of [14] Azariah, the son of [15] Zephaniah; the son of [16] Tahath, the son of [17] Assir, the son of [18] Ebiasaph, the son of [19] Korah” (verses 18-22). This final individual, Korah (“son of Izhar, the son of Kohath, the son of Levi, the son of Israel”; verse 23), is the individual who rebelled against Moses during the Exodus sojourn (Numbers 16).

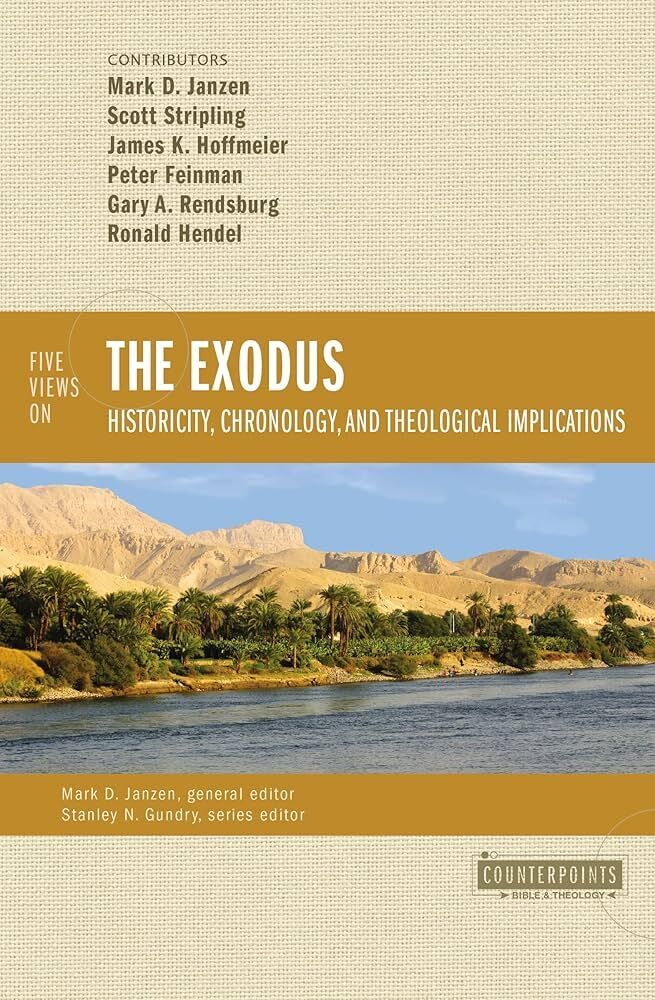

Of this genealogy, early-date proponent Dr. Scott Stripling writes the following in his chapter “The Fifteenth-Century (Early-Date) Exodus View” in Five Views on the Exodus: Historicity, Chronology, and Theological Implications:

1 Chronicles 6 … presents a genealogy of the temple musicians from Heman in David’s time to Korah in Moses’s time, 18 [successive] generations altogether. Adding a 19th generation brings us back to Solomon [in order to compare to Solomon’s 480 years in 1 Kings 6:1]. Wide agreement exists among scholars today that a generation averages 25 years, so an approximate equation for estimating this time looks like this: 19 generations x 25 years = 475 years. When 475 is added to 967 b.c. (Solomon’s fourth regnal year), we land in the mid-15th century (1442 b.c.). If the exodus occurred in the mid-13th century, the average length of the nineteen generations from Korah to Solomon would be approximately 15.2 years. This is highly improbable, especially since not all the ancestors of Heman would have been firstborn.

In 1 Chronicles 6, then, we see a generational span matching with remarkable harmony to the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 (as well as, in turn, the 300 years of Judges 11:26). We have a series of individuals that aligns very comfortably within a 15th-century b.c.e. Exodus timeframe.

But as with the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 and 300 years of Judges 11:26, there are late-date rebuttals to this conclusion.

‘Doctored’

Egyptologist Prof. Gary Rendsburg is a late-date Exodus proponent, one who holds to an especially late view of events—namely, a 12th-century b.c.e. Exodus. In his chapter in Five Views on the Exodus—“The Twelfth-Century Exodus View”—he tackles this subject of generational lists, putting a premium on the much shorter generational list of King David found in Ruth 4:18-22 (and repeated in 1 Chronicles 2:5-15). “Unfortunately, the genealogy of David is the only one in the Bible that can be used for the purposes of dating the exodus,” he opines. He dismisses Heman’s 19-generation count of 1 Chronicles 6 as the product of later-period “doctoring.”

“[T]he years used by the early Hebrew prose writers bear little or no reality and cannot be used for chronological reconstruction,” he writes of passages such as 1 Kings 6:1 and Judges 11:26. “By contrast, the genealogical information conveyed in the Bible [Ruth 4:18-22] (save the doctored material in Chronicles) reflects an internal consistency” (emphasis added throughout).

In highlighting Ruth’s five successive generations from the Exodus-period individual Nahshon to David (Nahshon-Salmon-Boaz-Obed-Jesse-David), Rendsburg offers a longer average “generation” span—30 years (if not more)—to arrive at his proposed 12th-century b.c.e. Exodus date.

Is Ruth’s genealogy in conflict with the information found in Chronicles?

‘Lengthening’ vs. ‘Telescoping’

A typical answer to shorter genealogies, such as this one found in Ruth 4, is that it is not unusual for generations to be skipped in the Bible—particularly in genealogies of especially significant individuals, where only the most consequential figures are given. To this end, the biblical language of “father” and “son” is interchangeable with “grandfather” and “grandson,” and a statement of begettal does not have to mean the begettal of one’s immediately succeeding generation.

This generational “telescoping,” as it has been called, can be seen in a number of biblical cases. For example, in 1 Chronicles 1:17, where Shem’s grandsons are listed as his sons, and in 1 Chronicles 3:15, where Shallum is listed as the son of Josiah, rather than his grandson. Archaeological evidence points to the same story in Daniel 5, with Belshazzar as grandson of Nebuchadnezzar, rather than son—as well as in Isaiah 22, with Eliakim as grandson of Hilkiah, rather than son. The New Testament book of Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus is a key case in point exhibiting this telescoping—particularly in the four-generation jump from Jehoram to Uzziah (there is a fascinating theological reason for this—an article for another time).

Prof. Paul Ray writes that such short genealogies, including Ruth 4 and its parallel in 1 Chronicles 2, “exhibit fluidity, omitting unimportant names, thus they seem incomplete to Westerners. … [F]luidity is a common feature in genealogies. Unimportant names were omitted, usually in the middle of the genealogy, between the names of the lineage founder (and his sons), and the then living individuals at the end” (“The Story of Ruth: A Chronological and Genealogical Perspective”). Importantly, this omission of certain generational links is not reflective of biblical error (as would be the case, for the artificial addition—“doctoring”—of characters in a genealogy).

Still, Rendsburg argues against this interpretation. “Others may claim that the genealogy of David has been telescoped, that one or two or even more generations are missing from the lineage, and thereby dismiss this evidence and still argue for a 13th-century or even a 15th-century exodus. As anthropological studies have shown, however, lineage lengthening (the insertion of links in the genealogical chain) is far more common than lineage telescoping (the removal of links in the chain).” On this, he cites David Henige’s The Chronology of Oral Tradition: Quest for a Chimera, appealing to “comparative sociological information, including African tribal lineages.”

“[T]he genealogy of David is the only one in the Bible that may be used for the purpose of dating the exodus,” Rendsburg summarizes, identifying the “garbled” genealogies of Chronicles as having “undergone artificial lengthening” and thus “not serviceable for our present enterprise.” He goes on posit a controversial theory for dismissing these genealogies—that “neither Samuel [the prophet, a member of Heman’s genealogy] nor Zadok [the priest, contained in an earlier, likewise longer Chronicles genealogy] was a true Levite,” and that “when Chronicles was compiled in the fourth century b.c.e., there was a need to provide Samuel and Zadok with invented Levite genealogies. Accordingly neither of these genealogies bears any value for the issue at hand. As such, my earlier statement remains: the genealogy of David is the only one in the Bible that may be used for the purposes of dating the exodus” (ibid).

Could They Fit?

Naturally, for many Bible literalists, this line of reasoning will be impossible to swallow. Stripling, for his part, dismisses Rendsburg’s appeal to Henige’s research of African oral traditions. “The genealogies in question here are written and non-African—profound differences to biblical genealogies. Thus Rendsburg overstates his case.”

Egyptologist Prof. James Hoffmeier, himself a late-date proponent (13th century b.c.e.), recoils at Rendsburg’s arguments. “I have a great deal of respect for Gary A. Rendsburg,” he responds in a rejoinder in Five Views on the Exodus. “Ultimately, I find there are problems with his understanding of genealogies.” He then writes:

Rendsburg argues that David’s genealogy in Ruth 4:18-22 also favors a 12th-century exodus. This conclusion requires one to treat this list literally and exhaustively and to dismiss the longer genealogical lists as “doctored” (expanded), like Heman’s in 1 Chronicles. But this is not always the case in the ancient world. Egyptian genealogies and king lists at times omit individuals (e.g. Hatshepsut), portions of a dynasty, or even entire dynasties. The Abydos King List removed both Amarna period rulers and the Hyksos dynasties. I cannot cite a single case in which nonhistorical figures were added to embellish an Egyptian king list.

While accepting difficulty with the sheer number of generations attributed to Heman in 1 Chronicles 6, Hoffmeier suggests that they could potentially fit with a 13th-century Exodus view. In responding to Stripling’s interpretation of 1 Chronicles 6, he writes:

Stripling believes that Heman’s genealogy in 1 Chronicles 6:33-37 supports the 1446 exodus date. Since Heman was a contemporary of David, the 19 generations back to Korah (left Egypt at the exodus) would equate to 25 x 19 = 475, and when this is added to Solomon’s third year of 967 b.c., you arrive at the year 1442, which is close to 1446. However, since Korah was an adult at the exodus (cf. Numbers 16), only 18 generations should be counted. As I have argued earlier, fatherhood began around or before age 20, which is 18 x 20 = 360 and places you around 1327 b.c. Further, if you multiply 18 generations at an 18-year average, a date of 1291 b.c. results. Or if a 17-year average is used to calculate, 1273 is the date (Ramesses ii [Hoffmeier’s Exodus pharaoh] reigned 1279–1213). Obviously, one can play with the numbers and get a date to suit one’s chronology.

But can one? Isolated instances of fatherhood at the age of 17 are certainly conceivable. But could it be used as an average, across a full 18 generations? Stripling finds this difficult to swallow, saying it is “highly improbably, especially since not all the ancestors of Heman would have been firstborn.” Stripling also retorts that “[t]here are 19 men mentioned in this genealogy, and I counted only 18 generations. I then added a 19th generation to reach Solomon and synchronize with 1 Kings 6:1. So it is Hoffmeier’s misunderstanding, not mine.” Thus Stripling’s 19 generations, counted backward from 967 b.c.e., stands—and as such, even a 17-year average would be prior to the reign of Ramesses ii; the real average would have to be less, more likely in the realm of 15 to 16 years (as calculated by Stripling). Which is to say, not “likely” at all.

It is interesting to observe different proponents toying with different generational length averages to support their theory—from under 20 years to 30 or more. Playing out such averages across such a large number of generations (as found in 1 Chronicles 6) creates an enormous margin of error. But we need not play with the numbers to such an extraordinary extent. In observing the generations in 1 Chronicles 6, we can tighten up the timeframe a little further (taking Heman’s genealogy literally in spite of Rendsburg’s argument).

Anchoring Samuel

Heman’s genealogy, as stated already, is the Prophet Samuel’s genealogy (with Samuel’s father as one and the same Elkanah—1 Samuel 1—and his son as one and the same Joel—1 Samuel 8:2). Thus, we can separate Samuel’s son Joel, grandson Heman, and hypothetical great-grandson (to give the parallel generation to the time of Solomon and 1 Kings 6:1), and look more closely at the internal evidence for when Samuel was on the scene.

In light of David’s reign beginning around 1011 to 1010 b.c.e. (calculated from Solomon’s fourth year and building of the temple in 967 b.c.e.), Samuel’s birth can be placed, very roughly, at around 1100 b.c.e., or perhaps a decade prior. Granted, there is some level of debate about the length of King Saul’s reign prior to that of David’s. As argued in “How Long Was the Reign of King Saul?”, based on a number of biblical clues (e.g. 1 Samuel 13:1; 1 Samuel 9; 2 Samuel 2:10, compared with Acts 13:21 and Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews 6.14.9), his reign should best be given as 42 years, thus beginning circa 1053 b.c.e.

The Bible does not specify how long prior to Saul’s reign Samuel served as judge (although there are clues); Josephus gives 12 years, which I would consider an undercount. Nonetheless, cumulatively, this would put the beginning of Samuel’s judgeship very roughly at around 1065 b.c.e. (if not earlier). 1 Samuel 7:2-3 points to this judgeship beginning 20 years after the ark of the covenant was moved to Kirjath-jearim—thus circa 1085 b.c.e.—which in turn was within a year of the initial taking of the ark by the Philistines (1 Samuel 6:1, 21). This capture of the ark was at the end of the life of the elderly priest Eli, while Samuel was evidently still a young man (1 Samuel 3). Collectively, these data points converge on the Prophet Samuel’s birth occurring somewhere in the realm of 1100 b.c.e., or slightly earlier. Given that Samuel died an elderly man in the years prior to David’s reign (e.g. 1 Samuel 28:14), this birth date would certainly fit, putting his death at around 80 or so.

We have, then, 16 generations back to Korah from Samuel. I tend to agree with Rendsburg that 30 or more years would be a good generational average to go with under normal circumstances (something we witness, for example, in the seven generations from Arphaxad to Nahor; Genesis 11:12-24)—especially due to some flux with the expectation of later-borns within such genealogies. However, in the case of Heman’s chronology, we have an especially long generational list (as compared to all other data, such as an earlier generational list of Zadok), and it seems logical that at least a comparatively tighter average would have been the case across this particular spread.

Therefore, applying Stripling’s shorter 25-year generational average would put Korah’s birth circa 1500 b.c.e. and his son Ebiasaph’s circa 1475 b.c.e. This fits squarely with the early Exodus date (circa 1446 b.c.e.) in light of a number of other clues given in the Exodus account—implying Korah as an older man and leader in the community at the time of the Exodus, with sons certainly on the scene during the sojourn (who survived the Numbers 16 incident; Numbers 26:11). These dates for Korah and Ebiasaph—even shunting them backward or forward by several decades (the latter, if going with other more minimalist interpretations of the lengths of Samuel’s judgeship and Saul’s reign)—fit tidily within the outline of a 15th-century b.c.e. Exodus. Certainly not within a late-date 13th-century b.c.e. Exodus timeframe (much less 12th century b.c.e.).

But we do not need to simply hypothesize conceptual lengths of generations. We can compare real-world examples.

Historical Examples

Take the British royal family: Applying the equivalent number of generations as that of Heman to Korah to the current youngest royal in line for the throne—Prince George (b. 2013)—takes us back to his ancestor Dietrich, Count of Oldenburg, who was born in 1398 and died in 1440. We have here 615 years worth of 18 successive generations to the birth of George, equating to a 34.2-year average; adding a 19th successive generation on this basis would give us a total of 644 years.

What about the likewise readily traceable Habsburg lineage, culminating in the final ruler, Charles i of Austria (1887–1922)? This takes us back to John i, Duke of Lorraine, on the scene from 1346 to 1390; 541 years in 18 successive generations to the birth of Charles i, and including Charles i’s son Otto von Habsburg (1912–2011) as the 19th successive generation gives us a total of 566 years, with an average of 29.8 years per generation.

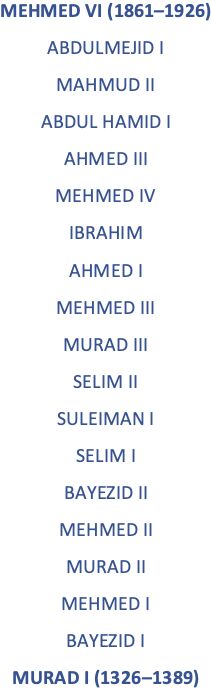

The story is the same for the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Mehmed vi (1861–1926); his respective ancestor is Murad i (1326–1389). 1861 minus 1326 gives 535 years from first to 19th generation (18 successively); adding Mehmed vi’s son Şehzade Mehmed Ertuğrul (1912–1944) as 19th successive generation would give us 586 years, averaging 30.1 years per generation.

Or take the Ethiopian “Solomonic Dynasty,” culminating in the final king-in-exile, Amha Selassie (1916–1997, son of the famous Emperor Haile Selassie). The same number of generations takes us back to Dawit i, who died in 1413. Dawit i’s date of birth is uncertain, but his reign began circa 1382. Assuming he was born at least 20 years prior, this would give 554 years from his birth to that of Amha, his 18th successive descendant; to Amha’s son, Crown Prince Zera Yacob Amha Selassie (b. 1953), we would have 591 years, with a generational average of 31.1 years.

I would be remiss not to include my own family tree. Granted, I have not (yet) been able to trace 19 generations paternally; nevertheless, with a handful of matrilineal links, 19 generations takes me to Baron Robert St Lawrence, circa 1435–1486—557 years from his birth to mine, or 587 years from his birth to the birth of my firstborn (b. 2022)—a 30.9-year generational average.

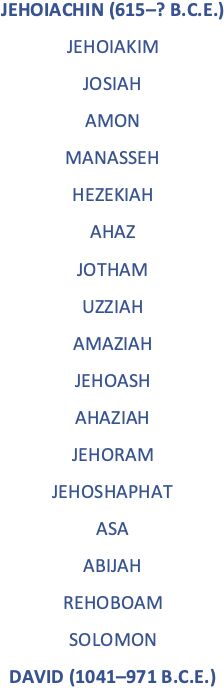

We can do the same for the biblical lineage of King David. With David in first position (in equivalent place of Korah), 18 successive generations takes us to the second-to-last king of Judah, Jehoiachin (in equivalent place of Heman). David’s reign ended circa 971 b.c.e., with his death at about the age of 70 (2 Samuel 5:4-5), placing his birth circa 1041 b.c.e. Jehoiachin’s short three-month reign is generally dated to 597 b.c.e.; having assumed the throne at the age of 18 (2 Kings 24:8), this places his birth circa 615 b.c.e. These 18 successive generations equate to a comparatively shorter total of 426 years, averaging 23.7 years per generation; adding this figure to get to a 19th generation descendant (since no numerical data is given for Jehoiachin’s descendants) would give us a total of 450 years.

What about simply comparing this period to the royal Egyptian family trees, culminating in Pharaoh Psusennes ii, who was on the scene during Solomon’s reign? Actually, certain of these pharaonic genealogies are notoriously difficult to ascertain, and speculation of descent abounds. Furthermore, “dynasties” are divided by rulers with common origin—and for this period, we cross several (the 18th to 21st Dynasties). Nonetheless, tracing the equivalent number of generations (and, where necessary, skipping to an equivalent-age individual from another family line) takes us back to Thutmose iii or Amenhotep ii—both 15th-century pharaohs, the latter of which happens to be a primary early-date candidate for pharaoh of the Exodus.

Cumulatively, these calculations demonstrate the impossibility of fitting Heman’s genealogy within a late-date, 13th-century b.c.e. Exodus timeframe. Even a 14th-century timeframe would be a stretch. Assuming Heman’s offspring (the 19th generation from Korah) to have been born roughly around 1000 b.c.e. (around the time Heman began his service during the reign of David), we can apply our above examples: With the extremely long British royal equivalent, this would place Korah’s birth as early as 1644 b.c.e.; with the Ethiopian equivalent, 1591 b.c.e.; that of my own family, 1587 b.c.e.; the Ottoman equivalent, 1586 b.c.e.; the Habsburg, 1566 b.c.e.; and on the other end of the spectrum, with David’s much shorter equivalent, 1450 b.c.e. Once again, these are calculations that only align with the early Exodus view—for example, the circa 1446 b.c.e. Exodus view logically putting the birth of Korah either at the end of the 16th or start of the 15th century b.c.e.

With the generational list of Heman in 1 Chronicles 6, then, we have a piece of evidence fitting in remarkable congruity with the other internal biblical Exodus data points—namely, the 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 and the 300 years of Judges 11:26. All three data points, taken together, triangulate on the same timeframe—the 15th-century Exodus view. Dismissing each data point in isolation is one thing, as is commonly done; it is another to account for the harmony across all three as merely coincidental, especially given the fact that all three are independent and differing types of calculation—one a generational list, another a judge’s military correspondence, and another a temple dedication inscription. In the words of Prof. Ronald Hendel, such passages represent “unambiguous biblical testimony for the date of the exodus,” in contrast to late-date theories, which represent a “departure from the plain sense of the Bible” (“The Exodus as Cultural Memory View,” Five Views on the Exodus).

Of course, as we have summarized elsewhere, these are far from the only data points indicating an Exodus during the 15th century b.c.e. Nevertheless, they represent the three key biblical passages popularly used to this end—and given their remarkable synchronicity, justifiably so.

Read More:

What Is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?

The ‘480 Years’ of 1 Kings 6:1: Just a Symbolic Number?

Jephthah’s ‘Three Hundred Years’: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The ‘Raamses’ of Exodus 1:11: Timestamp of Authorship? Or Anachronism?

The Book of Judges Fails to Mention an Egyptian Presence in Canaan—Or Does It?

Manetho’s Exodus Pharaoh, ‘Amenophis’ (Amenhotep): Any Reason to Doubt?

Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?

Jericho, Ai, Hazor: Investigating the Three Cities ‘That Did Joshua Burn’

Shiloh Sacrifices: Canaanite Or Israelite?

Amenhotep II as Exodus Pharaoh—With a Low Egyptian Chronology?