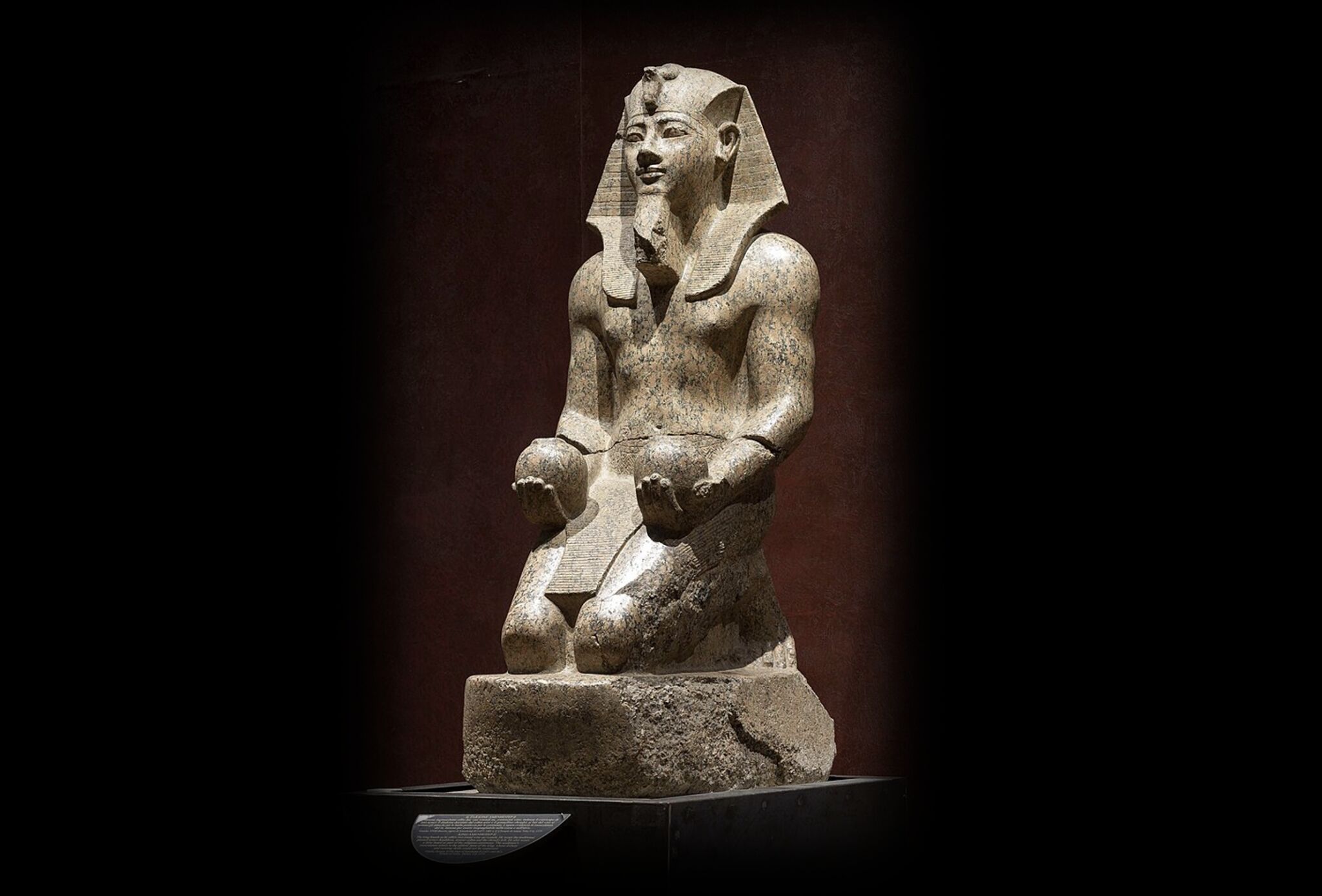

In “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?”, the case was made for the 15th-century b.c.e. pharaoh Amenhotep ii as pharaoh of the Exodus—based on a literal reading of 1 Kings 6:1, Judges 11:26, the genealogies of 1 Chronicles 6, the attestation of the early Egyptian historians Manetho and Chaeremon that the Exodus pharaoh was named “Amenophis” (Amenhotep), and a number of historical clues relating to the time period in question. This is known as an “early Exodus” position (distinct from the popular “late Exodus” view, which tends to favor the 13th century b.c.e., during the Ramesside period).

Our article used what is known as a “high chronology” of Egypt, which has Amenhotep ii reigning circa 1453–1426 b.c.e. This is a relatively popular dating scheme among proponents for Amenhotep ii as pharaoh of the Exodus. But high Egyptian chronology is not the most popular dating scheme among Egyptologists. Instead, it is low chronology, which down-dates these New Kingdom Period pharaohs by several decades.

This particular dating scheme has risen to overall prominence especially over the past several decades. As such, it is a point of criticism by late-date Exodus proponents against early-date, Amenhotep ii proponents: Against the backdrop of a supposedly settled low chronology, Amenhotep ii cannot be the pharaoh of the early Exodus. Instead, his reign would date to around 1427–1401 b.c.e.—only beginning some two decades after a 1446 b.c.e., early-date Exodus would have occurred.

Is low chronology the death blow to the Amenhotep ii-as-Exodus-pharaoh theory? Not so fast.

1 Kings 6:1: MT vs. LXX

The 1446 b.c.e. Exodus date is derived specifically from a chronological anchor to the building of Solomon’s temple. 1 Kings 6:1 says that this building project began in the 480th year from the Exodus. This temple building date has been rather remarkably pinpointed by different scholars using entirely different means and sources to 967 b.c.e.—a date for which there is virtual unanimity (variant schemes differ by only as much as a year or two). Counting back 479 years (since the building took place in the 480th year) takes us back to 1446 b.c.e. for the Exodus. (Note that this timeframe, and other scriptures in the Bible backing it up, entirely contradicts the late-date Exodus view; late-date proponents have a number of explanations for their dismissal of such passages. See the list of articles at the end for more information.)

On a low Egyptian chronology system, this 1446 b.c.e. date would put the Exodus well prior to the reign of Amenhotep ii. Instead, it would put it right in the middle of the surging reign of what would arguably become Egypt’s greatest pharaoh: Thutmose iii. (This father of Amenhotep ii, in our scheme, is identified as the primary pharaoh of the oppression.)

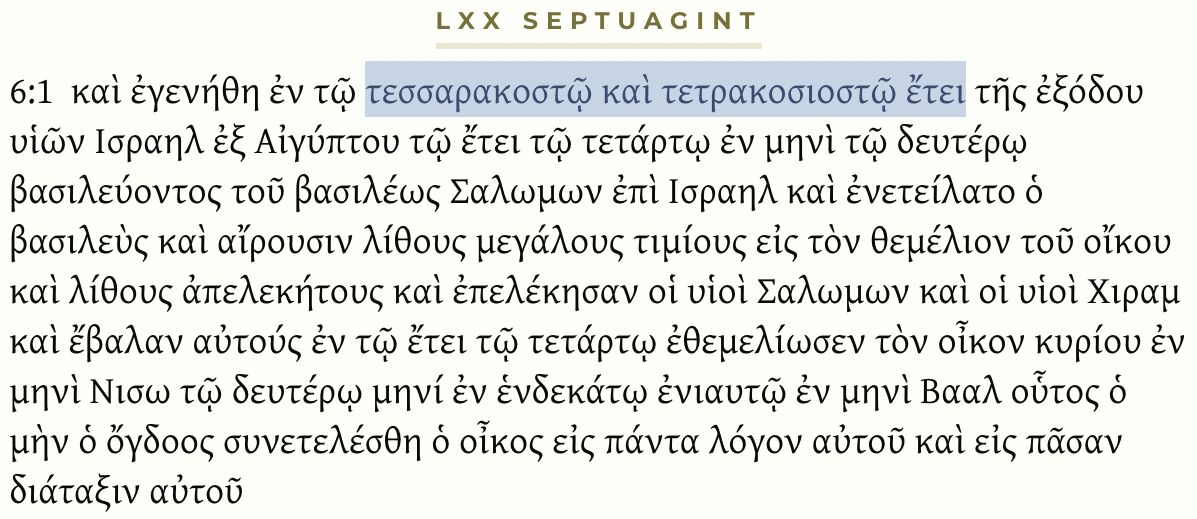

The 480 years of 1 Kings 6:1 is a key piece of information in determining the Exodus date, but there is a prominent textual variant of this verse. This is preserved in the Greek Septuagint (lxx), within a book of the Hebrew Bible translated into Greek during the second century b.c.e. This verse reads: “And it came to pass in the four hundred and fortieth year after the departure of the children of Israel out of Egypt” the temple began to be built (Brenton translation of the lxx). This specifies 440 years as opposed to the “four hundred and eightieth year” found in the Masoretic Text (mt) of the Hebrew Bible.

Putting the lxx’s 440 years together with temple-building date of 967 b.c.e. places the Exodus at 1406 b.c.e. Putting this together with the low Egyptian chronology scheme, this would indeed fall within the reign of Amenhotep ii—more specifically, near the end of his reign. It would, in turn, line up with the other parallels highlighted in “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?”—such as the conquest of Canaan beginning 40 years later (1366 b.c.e.) at the end of the reign of Amenhotep iii (1391–1353 b.c.e.) on into the reign of Akhenaten (1353–1336 b.c.e.), as accounted in the Amarna Letters.

The question might be asked: Would this 440-year period conflict with the roughly “three hundred years” (Judges 11:26) given by the judge Jephthah as being the general span of time from when Israel had entered the land to his time period? Not at all. The Jephthah episode is often put at around 1100 b.c.e.—thus putting the entry into Canaan 300 years earlier, roughly 1400 b.c.e. Yet here again, the conclusion is the same. As pointed out in “Jephthah’s ‘Three Hundred Years’: Evidence for the Early Exodus,” Jephthah’s interaction with the Ammonites may be more closely dated to 1090 b.c.e. Whatever the case, a conquest in 1406 would put his rounded 300-year statement as being slightly less than the total (perhaps by a decade or two); conversely, with a 1366 b.c.e. conquest, it would put the 300 years as slightly more than the total (perhaps by a few decades). In any event, there is some flex in the dating of Jephthah (based on the debate about Saul’s regnal length, as well as the length of Samuel’s judgeship)—but the general 300 year period still fits for either scheme.

It is a matter of debate as to why the lxx gives 440 years between the Exodus and the building of the temple as opposed to the 480 years of the Masoretic Text (the text used in most Bible translations). One option is that such numbers in the biblical text were originally written with symbols and were only later transcribed into full words (i.e. “480” versus “four hundred and eighty”)—and that this may have simply been the result of a scribal error in reading the original symbol.

My contention is that the mt’s 480-year period is correct alongside the high chronology scheme. Further, it is my contention that the chain of events in ancient Egyptian history (as highlighted in “Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?”)—from Kamose, the pharaoh who “knew not Joseph,” to Hatshepsut as the biblical pharaoh’s daughter, to Moses fleeing during the reign of Thutmose iii, to Amenhotep ii as Exodus pharaoh, all the way to Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten, pharaohs during the conquest of Canaan—is too perfect to be anything other than a fit for the chain of biblical events. But those who may take issue with this particular interpretation of Egyptian chronology may draw the very same conclusions with low chronology and the lxx’s 440 years.

High vs. Low—and Everything in Between

But what about the high vs. low chronology? Is Egyptian chronology settled?

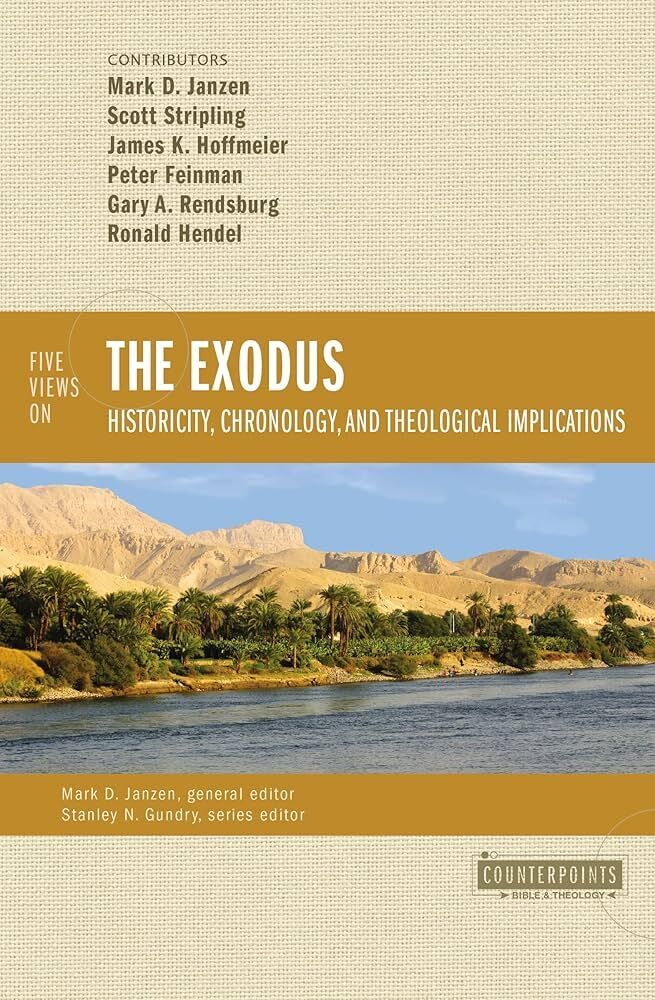

Far from it. Certainly, the low chronology is currently the more widely preferred scheme among scholars. “During the 1980s–1990s a series of conferences on absolute chronology led most Egyptologists to favor the lower dates for New Kingdom,” summarized Prof. James Hoffmeier in Five Views on the Exodus: Historicity, Chronology, and Theological Implications.

Nevertheless, there do remain proponents for the high chronology, as well as a number of other chronological variants besides. Often, in the conversation about Egyptian chronology, the two schemes are discussed. But there is actually a third variant known as middle chronology (which is rarely mentioned, as it has comparatively few adherents). There are additional variations of these three primary schemes, as well as other entirely different schemes (including the more extreme variants of the chronological revisionists, such as that of David Rohl). Adherents for each often characterize their preferred chronology as absolute and settled—to the point that others must be well-nigh crazy or stupid not to agree. (And yes, I’ve received impassioned correspondence along these lines from proponents for all three chronologies—high, middle and low.)

But why has low chronology succeeded—for now—as the most oft-cited, oft-used Egyptian chronological scheme? As we have covered, using either low chronology or high, the same case can be made for Amenhotep ii as pharaoh of the Exodus. But does current research upend high chronology?

Enter Burna-buriash ii and Assur-uballit i.

Do BBII and AUI Prove Low Chronology?

Some time ago, I received the following e-mail from a reader, relaying his “concern” in my “reliance on a higher Egyptian chronology in order for Amenhotep ii to be the reigning pharaoh in 1446 b.c., with Amenhotep iii reigning until 1370 b.c.” He went on:

But that is impossible due to synchronisms with Mesopotamia. Burna-buriash ii of Babylon wrote letter ea 6 to Amenhotep iii, and Burna-buriash ii reigned from 1359–1333 b.c. His dates are secure due to synchronisms with Assyria [namely Assur-uballit i] and cannot be raised any higher. Which means the low Egyptian chronology (for Dynasty 18) is correct and Amenhotep iii reigned from 1388–1350 b.c. Amenhotep ii then reigned from 1425–1397 b.c. [this individual here using another low Egyptian chronology variant].

“The Babylonian timeline simply does not allow for higher dates for the 18th Dynasty,” he concludes.

This has indeed been part of the basis for the more widespread adoption of low Egyptian chronology. The Amarna Letters of Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten contain correspondence from Babylon’s Kassite Dynasty king, Burna-buriash ii, and Assyria’s first Middle Assyrian king, Assur-uballit i. More specifically, Burna-buriash ii corresponded with Amenhotep iii right at the end of the pharaoh’s reign and then continued to later correspond with his son, Akhenaten. This means that the Babylonian king’s reign overlaps with the very end of the reign of Amenhotep iii. With the start of Burna-buriash ii’s reign in 1359 b.c.e.—a reign that allegedly “cannot be raised any higher”—this only fits with a low Egyptian chronology with Amenhotep iii’s reign ending shortly thereafter.

Debate settled?

Note that this dispute is not about whether or not Burna-buriash ii wrote letters to Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten. We are not attempting to take Burna-buriash ii out of the reign of Amenhotep iii and Akhenaten—that synchronism is there—we are simply on a sliding rule about where to place the reigns of all three. So, is it really true that Burna-buriash ii’s “dates are secure due to synchronisms with Assyria and cannot be raised any higher”?

A Note on Mesopotamian Chronology

What we are dealing with in the round, then, is an overall Mesopotamian chronological system as compared with the Egyptian chronological system. Synchronisms between these two systems do exist (such as that of Burna-buriash ii/Assur-uballit i and Amenhotep iii/Akhenaten), although they are fewer and farther between. How certain and secure are these Mesopotamian dates?

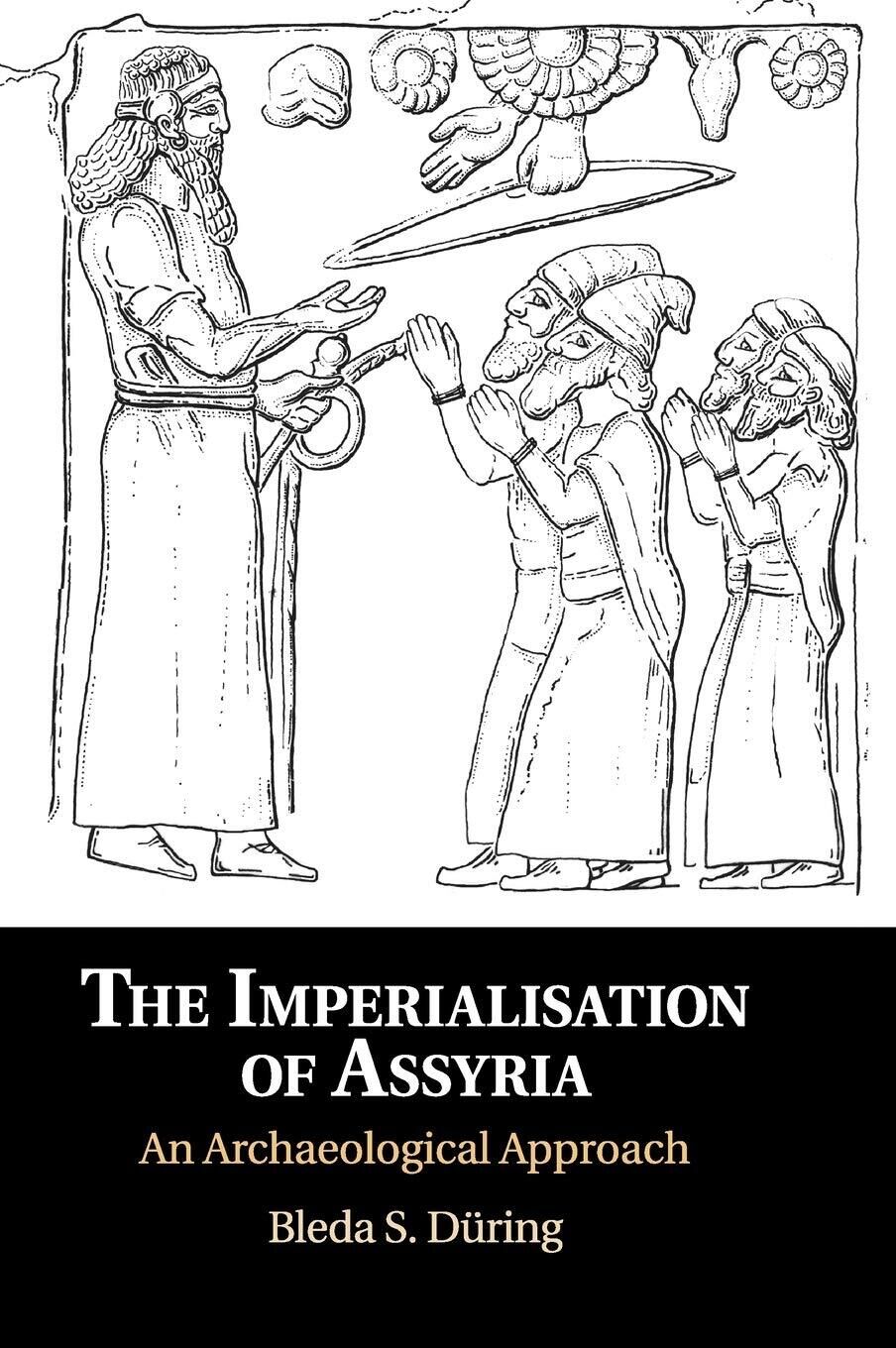

We have touched on the three Egyptian chronological schemes—high, middle and low. When it comes to Mesopotamian chronology, it is instructive to review the rather extraordinary summary of Prof. Bleda S. Düring in his 2020 book The Imperialisation of Assyria: An Archaeological Approach: “In Mesopotamian history a considerable amount of controversy exists on how to date various events and kings, and various scholars have proposed five alternative dating schemes for Mesopotamia: The so-called high chronology, middle chronology, modified middle chronology, low chronology and ultra low chronology.” Professor Düring goes on:

Various recent monographs and many additional studies have been devoted to assessing the plausibility and effectiveness of these chronologies, the assessment of which is akin to opening Pandora’s box. While many archaeologists have favored the ultra low chronology, or new chronology … historians and many Near Eastern archaeologists have largely continued to use the middle chronology or orthodox chronology mainly because to accept the new chronology would result in a large number of new chronological problems or would cause confusion amongst colleagues.

Some years ago, two systematic studies devoted to the evaluation of these chronologies by Furlong and Newgrosh concurred that the new chronology is the most robust one. This conclusion was based primarily on radiocarbon dates, which appeared to fit the new chronology best at the time. In general, ancient historians were much less willing to accept the new chronology for two main reasons. For historical reconstructions the new chronology has very profound consequences, which for example the current synchronisations between Hittite and Middle Assyrian histories [the time period of Assur-uballit i] completely disappear. New historical scenarios have been proposed, such as a war between Tiglath-pileser i and the Hittites, whereas in traditional chronologies Tiglath-pileser i ruled some seventy years after the collapse of the Hittite Empire. Moreover, the various proposals of new historical chronologies diverge widely from each other in their absolute dates and their proposed synchronisations of various historical sequences.

“Clearly, these arguments are as much about reputations and academic allegiances, as they are about chronology,” Düring concludes. And, despite his own stated preference for the modified middle chronology, he establishes that “[f]or the purpose of this book … it is best to avoid these chronological issues, given that they cannot be resolved easily …. Therefore, I will adhere to the, possibly erroneous, middle chronology dates in this book.”

It’s a rather stunning admission. But even more than this “Pandora’s box” of Mesopotamian chronologies is the foundation the box is sitting on. In a sense, this debate about the history of the ancient Near East has a key component of circular reasoning. That’s because, in general, it is fundamentally underwritten by the Egyptian chronology used. Therefore, a low Egyptian chronology will result in a lower Mesopotamian chronology; conversely, a high Egyptian chronology will result in a higher Mesopotamian chronology.

In the words of Egyptologist Dr. Kent Weeks (emphasis added):

The chronology of Egypt is still a lot better founded than the chronology of most other parts of the ancient Near East, which means that Egyptologists have two great problems here in dealing with chronology. One is to get a chronology that is internally consistent and satisfies the needs of those people working in Egypt; but then the other is to get a chronology that will be accepted by scholars in other areas of the ancient Near East, because when all is said and done, it’s the Egyptian chronology that underpins everything else that’s being done throughout the rest of the known world. It’s a big responsibility—a heavy burden—and it’s one of the reasons that people look at it so closely, because in terms of reconstructing ancient history, a lot hinges on the answers” (interview, “Questioning the Timeline of the Ancient World”).

Dr. John Bimson notes the same: “The Late Bronze Age, all around the Mediterranean, is dated because of its links with Egypt” (ibid).

We are left more or less arguing in circles. Egyptian dates are used to “prove” Mesopotamian dates, and Mesopotamian dates are used to “prove” Egyptian dates. Therefore, if a high Egyptian chronology exists, it requires a high Mesopotamian chronology. If a low Egyptian chronology is used, it requires a middle-lower Mesopotamian chronology.

Regarding Burna-buriash ii, examples of variant higher schemes put his reign around 1392–1367 b.c.e. or 1375–1347 b.c.e.; lower schemes put it around 1359–1333 b.c.e. (Again, I prefer the high chronologies—not simply out of favor for the Masoretic Text’s 1 Kings 6:1—but due a number of other synchronisms, particularly within the earlier part of the second millennium b.c.e. But that’s another article for another day.)

Whatever the answer, at the end of the day, one thing remains true: low chronology in no way disqualifies Amenhotep ii as pharaoh of the Exodus. We have two admissible and plausible scenarios: that a high Egyptian chronology is correct, a higher Mesopotamian chronology is correct, and the mt version of 1 Kings 6:1 is correct—thus Amenhotep ii is pharaoh of the Exodus; or that the low Egyptian chronology is correct, a middle/low Mesopotamian chronology is correct, and the lxx version of 1 Kings 6:1 is correct—thus Amenhotep ii is pharaoh of the Exodus.

Read More:

What Is the Correct Time Frame for the Exodus and Conquest of the Promised Land?

The ‘480 Years’ of 1 Kings 6:1: Just a Symbolic Number?

Jephthah’s ‘Three Hundred Years’: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The 19 Generations of 1 Chronicles 6: Evidence for the Early Exodus

The ‘Raamses’ of Exodus 1:11: Timestamp of Authorship? Or Anachronism?

The Book of Judges Fails to Mention an Egyptian Presence in Canaan—Or Does It?

Manetho’s Exodus Pharaoh, ‘Amenophis’ (Amenhotep): Any Reason to Doubt?

Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

The Amarna Letters: Proof of Israel’s Invasion of Canaan?

Jericho, Ai, Hazor: Investigating the Three Cities ‘That Did Joshua Burn’