Another year in biblical archaeology is behind us—and a big year it was, particularly in discoveries and research relating to kings David and Solomon.

What follows is our top 10 list of biblical archaeology discoveries for 2023. Some of these are in the form of individual small finds, some are broader site finds, and some are the product of general research and publication. Where applicable, our podcast videos with the researchers in question are posted below.

Enjoy!

10. ‘Oldest Known Gate’ in the Holy Land

In August, the Israel Antiquities Authority (iaa) announced the discovery at Tel Erani of the earliest known gate found in Israel, dated to the Early Bronze Age ib (circa 5,500 years ago). Tel Erani is a prominent city mound located in the Judean lowlands, northeast of the Gaza Strip.

The gate is preserved to a height of around 1.5 meters and consists of a large monolithic stone-and-mudbrick passageway, flanked by twin towers. Archaeologists also discovered a portion of a 7-to-8-meter-wide fortification system. According to excavation director Emily Bischoff: “This is the first time that such a large gate dating to the Early Bronze Age has been uncovered. … The fortification system is evidence of social organization that represents the beginning of urbanization.” (Read more about the discovery here.)

9. Monumental Middle Bronze Shimron

Archaeologists working at the northern site of Tel Shimron (between the Sea of Galilee and Haifa) discovered a massive, 3,800-year-old monumental structure. Shimron is a second millennium b.c.e. Canaanite city mentioned twice in the book of Joshua (Joshua 11:1; 19:15). Atop the tel, a 1,200-square-meter mudbrick complex raised the height of the already-prominent mound by an additional 5 meters. The complex may have had some kind of as-yet unknown religious significance.

Within the complex, a fully intact “corbelled vault” framed a descending passageway—the first such Mesopotamian-style arch ever found in southern Levant. The perfect preservation of the mudbrick archway, replete with decorative edging (all of which would typically disintegrate over time) was apparently due to the fact that it was filled in in antiquity with gravel. Only a short length of the descending passage has been investigated; the archaeologists, who have since refilled it (to maintain preservation), hope to return to the site to continue investigating where it goes. (Read more here.)

8. Patriarchal-Period Currency

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science concluded that silver pieces (“hacksilver”) were used as currency in the Levant during the Middle Bronze Age (first half of the second millennium b.c.e.). It was initially believed that silver currency hoards in the Southern Levant were an Iron Age (1200–586 b.c.e.) phenomenon. This discovery, however, sheds light on much earlier commercial interactions—at least as early as the 17th century b.c.e., some 500 years earlier than the generally accepted time frame.

Not every silver hoard can necessarily be designated a currency hoard. The latest report clarifies, however, that the hoards discovered at Gezer, Shiloh and Tel el-ʿAjjul were not found in the context of silversmith tools or a workshop (i.e., just production off-cuts). Rather, they were specifically collected for their intrinsic value, and hence were deemed silver currency hoards. There are no silver mines in Israel; isotopic testing shows the silver hoards to have originated in Turkey (the ancient territory of the Hittites)—thus, pointing to trade and/or political interactions with the region.

This discovery, and the time frame in question, parallels the biblical account of the use of weighed-out silver pieces as currency at the time of the biblical patriarchs (first half of the second millennium b.c.e.). For example, Abraham’s purchase of land from Ephron (himself a Hittite) in Genesis 23:16: “[A]nd Abraham weighed to Ephron the silver, which he had named in the hearing of the children of Heth, four hundred shekels of silver, current money with the merchant.” (Read more here, and the official publication here.)

7. Ancient Israelite DNA

The discovery of a rare, clean and clear First Temple Period Israelite family burial at Kirjath Jearim, with sufficiently preserved remains, has allowed archaeologists for the first time to recover ancient Israelite dna.

Kirjath Jearim is biblically significant (e.g. as a resting place for the ark of the covenant—1 Samuel 7:1). The use of this tomb dates to the eighth to seventh centuries b.c.e. While the dna retrieved belongs to just two individuals, it is an important start that researchers can use. It will open a significant door in the study of the ancient Israelites and their genetic makeup. (Read more here.)

6. Swords and ‘Salt’

This discovery made the top of National Geographic’s list of “most exciting” discoveries worldwide. Four perfectly-preserved, nearly 2,000-year-old Roman swords, as well as a pilum (a javelin-like spearhead), were discovered in a cave overlooking the Dead Sea. It appears that these weapons may have been in the possession of Jewish rebels hiding in this area at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–136 c.e.).

The items were discovered by Ariel University’s Dr. Asaf Gayer and his team while investigating another interesting feature of the cave: an incredibly rare, First Temple Period inscription inked on a stalactite, first discovered 50 years ago. The nine-line inscription is extremely fragmentary, however—Gayer and his team had set out to use multi-spectral imaging in order to try to read more of the lettering.

Their attempts were successful, in part. While we await the full report, Dr. Gayer has revealed that part of one line reads “in the Valley of Salt.” This terminology for the region is found throughout the biblical account (i.e. 2 Samuel 8:13; 2 Kings 14:7; 1 Chronicles 18:12). Furthermore, the spelling for “in the valley” on the stalactite is a particular variant spelling used in the biblical text. (Read more here and here.)

5. City of David ‘Moat’ and Bedrock Channels

If you thought you knew Jerusalem topography, think again! This year, a remarkable topographical feature was revealed in the City of David’s ongoing Givati Parking Lot excavations—a massive west-east void in the bedrock of the city, effectively separating the Ophel ridge to the north, and City of David ridge to the south.

Unfortunately, according to the excavators, there was “no direct evidence for dating the hewing of the ditch”—but nonetheless, “it was certainly in use prior to the Late Iron iia-Early Iron iib, at which point it was reused for a different purpose.” This moat-like ditch was evidently an intentional separation of the upper part of Jerusalem from the lower. In their report of the discovery, the researchers note the feature in the context of several other monumental Iron iia construction projects, including the Stepped Stone Structure/Large Stone Structure (King David’s palace) and Ophel royal quarter—“part of the same royal mindset that dramatically changed the urban landscape … in the formative moments of Iron Age Jerusalem.”

Together with the moat, a series of adjacent peculiar bedrock channels were discovered. Speculation abounds as to the reason for these finger-like channels—perhaps for soaking flax for the production of linen, or for the production of date honey. (Read more about the bedrock channels here and the research article on the moat here.)

4. Core Cities of David’s Kingdom

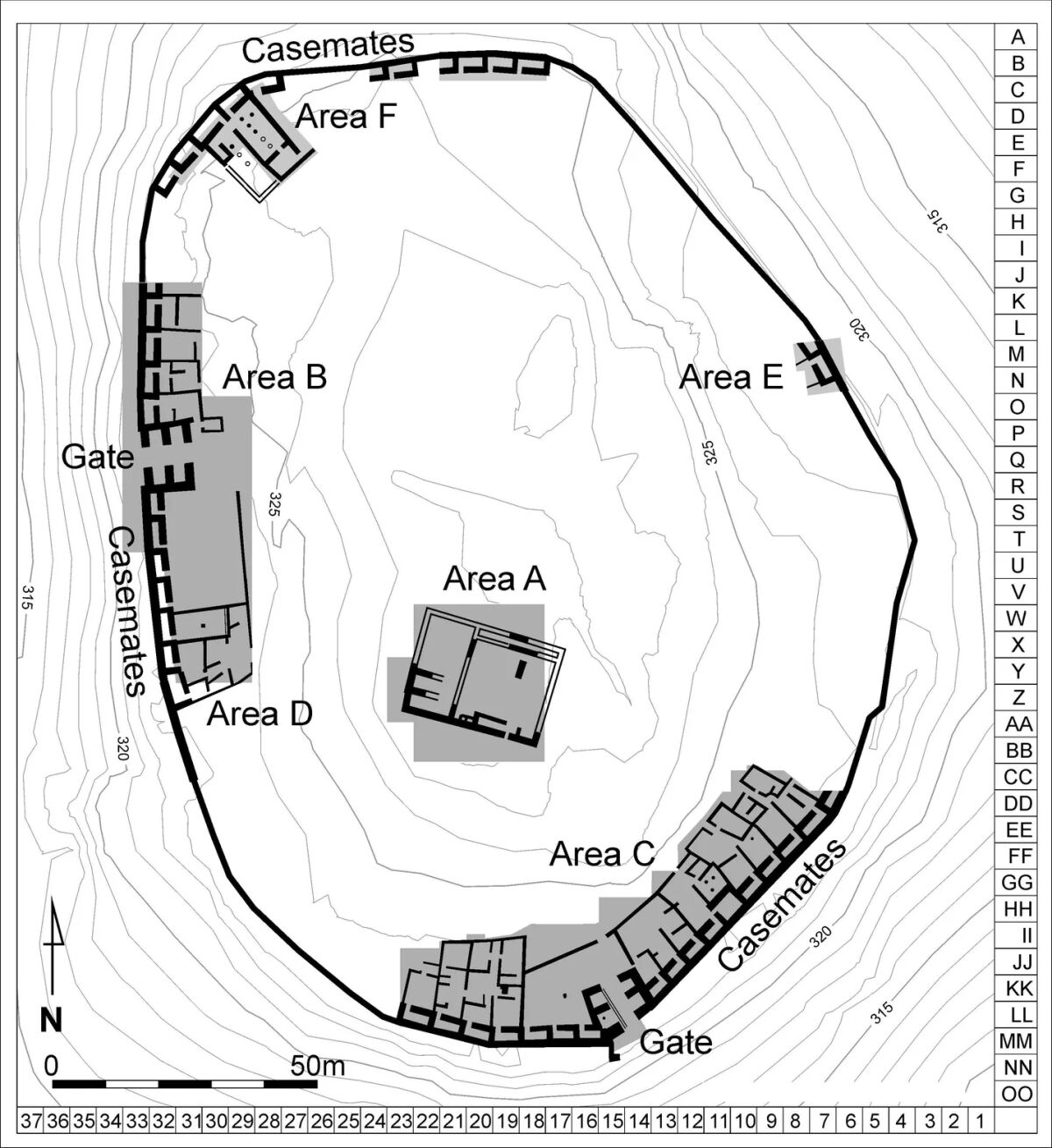

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel is well-known for his famous Davidic-period site Khirbet Qeiyafa—an unusual, largely single-use site radiocarbon-dated to an extremely tight window of use (between 1020–980 b.c.e.). Utilizing his discoveries at the site, Professor Garfinkel published a new research article in 2023 reviewing other, less-securely dated regional sites that parallel Khirbet Qeiyafa in layout and material culture: Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh, and Khirbet ed-Dawwara. He proposed them as evidence of an emerging 10th-century b.c.e., core administrative kingdom of David and Solomon (and later, Rehoboam).

Professor Garfinkel identified in particular a unique, Judean-style casemate wall construction around the cities, with a peripheral belt of residential buildings attached to and incorporating the casemate walls, as well as an inner peripheral street. He also noted parallel material cultures, logical geographical positioning of the cities in relation to one another, and a good fit in dating to within the early to mid-10th century b.c.e.

He demonstrated that these cities are evidence of a core, pre-planned Davidic kingdom that emerged at the time, reflecting deliberate city planning across the region and the expansion of the kingdom into the Shephelah (Judean lowlands) during the early 10th century b.c.e.

Finally, Garfinkel highlighted his recent excavations at Lachish, paralleling the above parameters, except for exhibiting a new, solid wall construction (instead of a casemate). The Bible states that David’s grandson Rehoboam fortified Lachish (2 Chronicles 11:9). After excavating the northeast corner of Lachish, Garfinkel’s team discovered a new, previously unknown, solid city wall. Through carbon dating, they were able to narrow its construction window to the end of the 10th century and beginning of the ninth, synchronizing well with the biblical period of Rehoboam. (Read more here and the official publication here.)

3. David’s Edomite Garrisons

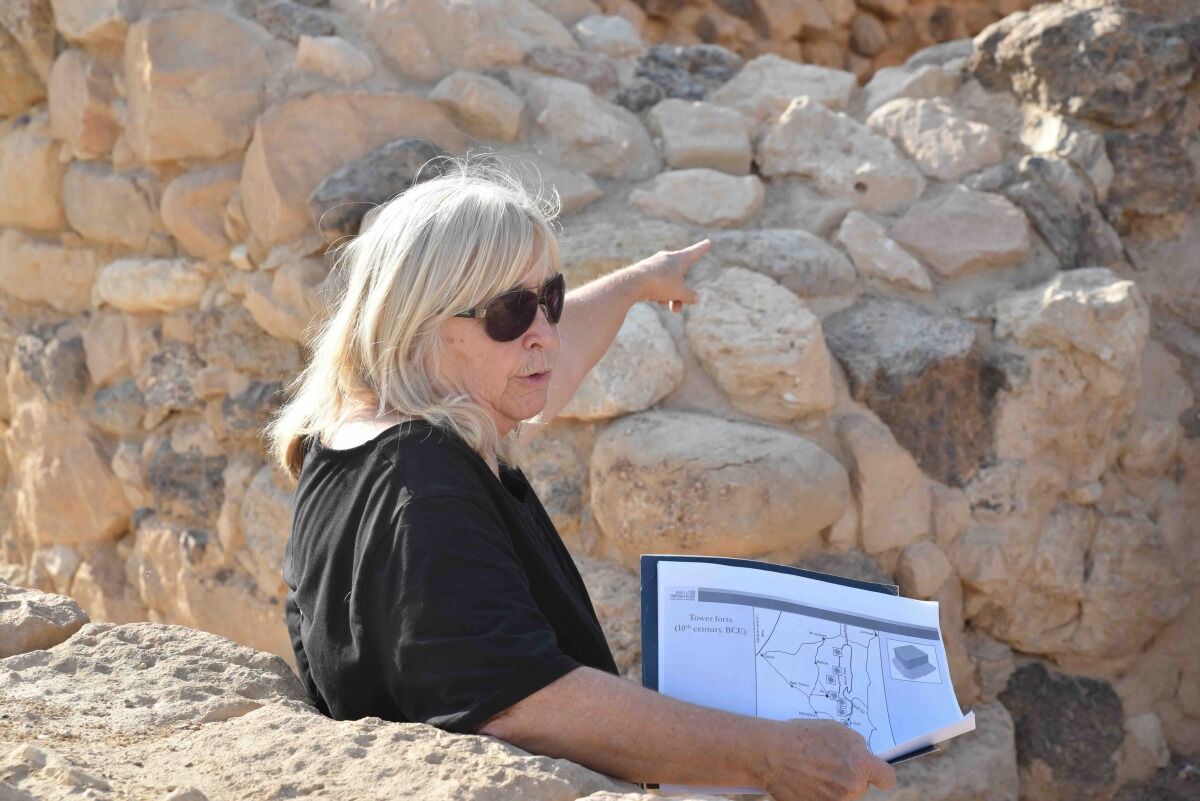

Following the outbreak of the war on October 7, in solidarity with the war effort, the iaa hosted an online lecture series titled “We Will Not Be Defeated: From Crisis to Revival in the Archaeology of the Land of Israel.” In her lecture, archaeologist and long-time inspector for the Southern Negev Dr. Tali Erickson-Gini presented a new compilation of evidence—the product of new and old research—demonstrating a chain of Davidic-era fortresses throughout the southern territory of Edom, paralleling several biblical verses that speak to the same. “And he [David] put garrisons in Edom; throughout all Edom put he garrisons, and all the Edomites became servants to David” (2 Samuel 8:14).

“Most people, even Israelis, are not so aware of the fact that 3,000 years ago, there were Hebrew soldiers there [in the Negev Highlands] and there were Hebrew fortresses there,” she stated in the presentation. She later told the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology in an interview that “most researchers are not even aware that they exist.” With sufficient evidence now accumulated, she felt it was time these discoveries were brought to the fore.

Erickson-Gini highlighted dozens of garrisons positioned throughout the southern territory, whose use dates to the early Iron Age—ending in the latter part of the 10th century b.c.e. (at the time of Pharaoh Shishak/Shoshenq i’s invasion). She highlighted the military nature of these outposts and the fact that they are guarding strategic locations. They have parallel layouts and Iron iia pottery culture—in some cases directly matching that found to the north, in 10th century Judahite sites. She also featured more recent discoveries, in particular at one fortress (Ein Hatzeva) whose remains were carbon-dated to the 10th century b.c.e., and the use of another (Har Eldad) whose remains were carbon-dated to around 1000 b.c.e.—the time period of King David.

Dr. Erickson-Gini concluded: “From my knowledge of these places, where they’re placed along the roads, the topography, I don’t think that there’s any doubt that we’re talking about something to do with some kind of fortifications in the Negev Highlands, and control of this region between Edom and the area of Judah under the united monarchy.” (Read more about this subject here, and watch her presentation here.)

2. Solomonic Gezer After All

Of all the discoveries this year, this one potentially proves the most consequential: A new radiocarbon dataset proves that Gezer’s Stratum 8—the impressive “Solomonic” city—does date to the early to mid-10th century b.c.e. after all.

For traditional archaeologists, this is not new news. Beginning with Prof. Yigael Yadin the 1950s, these monumental remains—most notably, a large six-chambered gate, paralleling six-chambered gatehouses discovered at Megiddo and Hazor—have been associated with the 10th-century reign of Solomon and 1 Kings 9:15: “And this is the account of the levy which king Solomon raised; to build … Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer.” Excavations at these three sites by Yadin, Prof. William Dever and Prof. Amnon Ben-Tor have served to reinforce this conclusion. In the last several decades, however, a prominent “low chronology” camp emerged, seeking to down-date such “Solomonic” remains to the ninth century b.c.e. Suffice it to say that sparks have flown in this debate, with Gezer’s Dever and Hazor’s Ben-Tor doggedly maintaining the original, 10th-century dating.

Regarding Gezer, one highlighted weakness in this debate was the lack of a thorough, radiocarbon-dated chronology. However, the carbon results of 10 seasons of excavations by the Tandy team at Gezer were finally published in 2023. Naturally, most of the interest in this report surrounded Stratum 8—the monumental gatehouse, palatial structure and casemate wall.

The radiocarbon samples taken from this stratum date resoundingly to “the first part of the 10th century b.c.e.” Not only that, samples taken from the following stratum that cancelled it out—Stratum 7—also date to the 10th century (the latter part). Taken together, this new evidence upends entirely the long-fought, revisionist ninth century low chronology theory for the site. (Read more about the discovery here.)

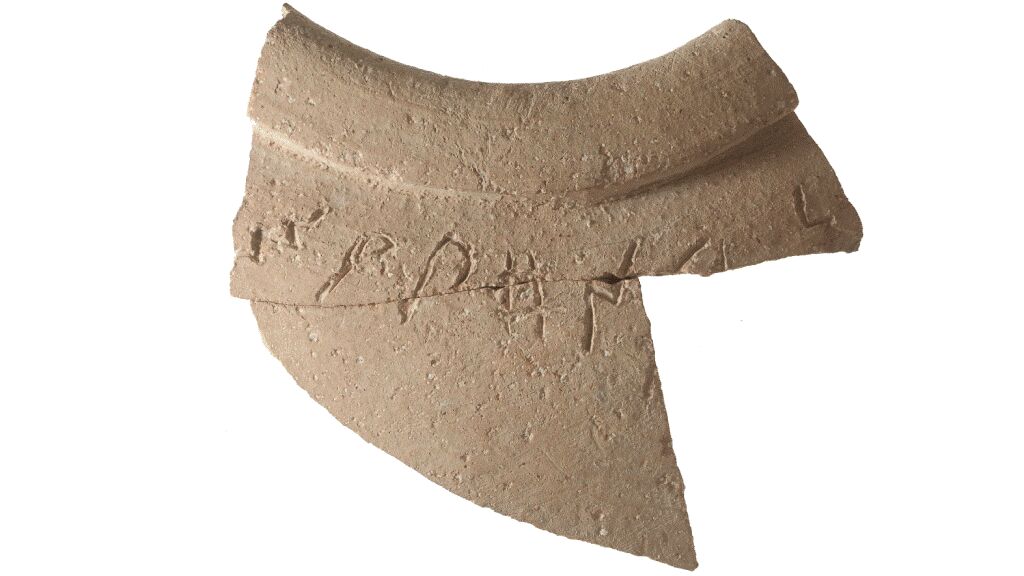

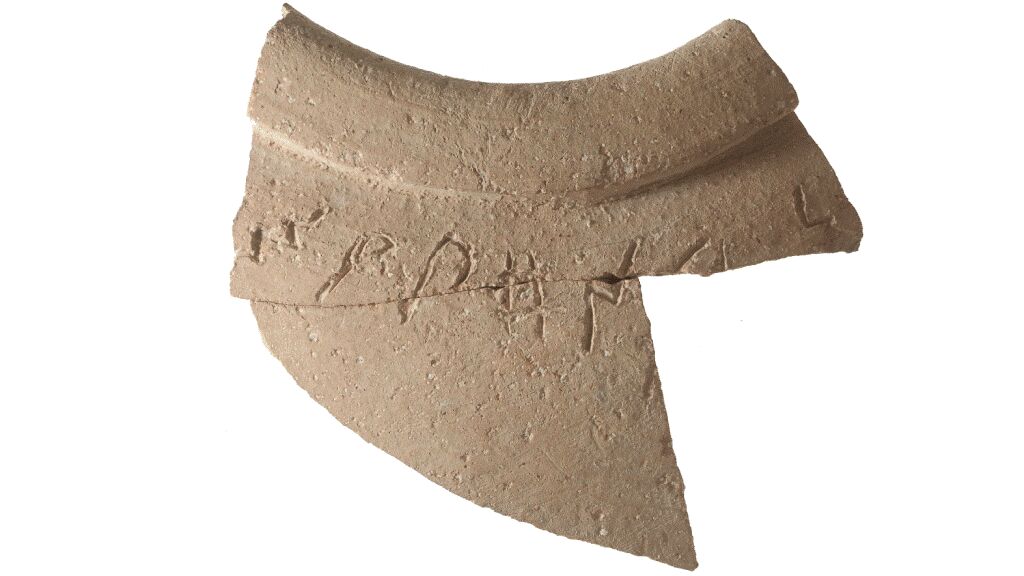

1. ‘Queen of Sheba’ Sherd

Forgive a little bias for this discovery. This item, known as the Ophel Pithos Inscription, was discovered by our team in 2012 on the Ophel, under the direction of our beloved Dr. Eilat Mazar. At the time, speculation abounded regarding the identity of this earliest alphabetic script ever discovered in Jerusalem. Was it Canaanite? Hebrew? Several letter forms looked odd for either option. The seven-letter text (broken at both ends) was explained with various tentative suggestions, but no real conclusions. A significant question mark remained over this item.

That is, until early 2023. Epigrapher Dr. Daniel Vainstub, who had been studying the enigmatic Ancient South Arabian (asa) script, returned to this item, noting that all of the otherwise-peculiar letter forms have good parallel with the South Arabian script. Furthermore, in recognizing the text as asa, he was able to propose the following reading: “…]šy ladanum, 5 […”

Ladanum (Cistus ladaniferus) is an incense ingredient and particular item of trade known from the southern Arabian peninsula (the territory of Saba/Sheba). It is identified with the biblical tabernacle/temple incense ingredient שחלת (i.e. Exodus 30:34). To this end, the location of the sherd was also notable, given its proximity to the temple—found barely 50 meters from the Temple Mount. Furthermore, the asa letter representing the quantity five is a good fit, given that these pithoi are known to have a volume of five ephahs (a standard biblical measurement).

Given all of this, alongside the 10th-century b.c.e. dating of the sherd, Dr. Vainstub noted the item as a good parallel to the biblical account of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon, “with a very great train, with camels that bore spices” (1 Kings 10:2). The artifact logically constitutes evidence for the establishment of such “spice” trade between the kingdoms. “[T]here came no more such abundance of spices as these which the queen of Sheba gave to king Solomon” (verse 10). (Read more about the discovery here and the official publication in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology here.)

Stay Tuned …

As big as 2023 was, 2024 also looks to be promising, with several ongoing projects. Not least of which, the Siloam Pool excavation (despite some sorely flawed “reporting” about the site, including that the team has found “almost nothing.” What they have found is actually extremely interesting and will reshape our understanding of this lower part of the City of David).

Of course, the prospect of continuing excavations is against the tragic backdrop of war, with many of our friends called up to the front. Still others have had their expertise in archaeology requisitioned to sift through the remains of the October 7 massacre—a grisly and traumatic task for the team.

Nevertheless, at least for those not called up, the research into the past continues apace. It must. So stay tuned—big things are coming.