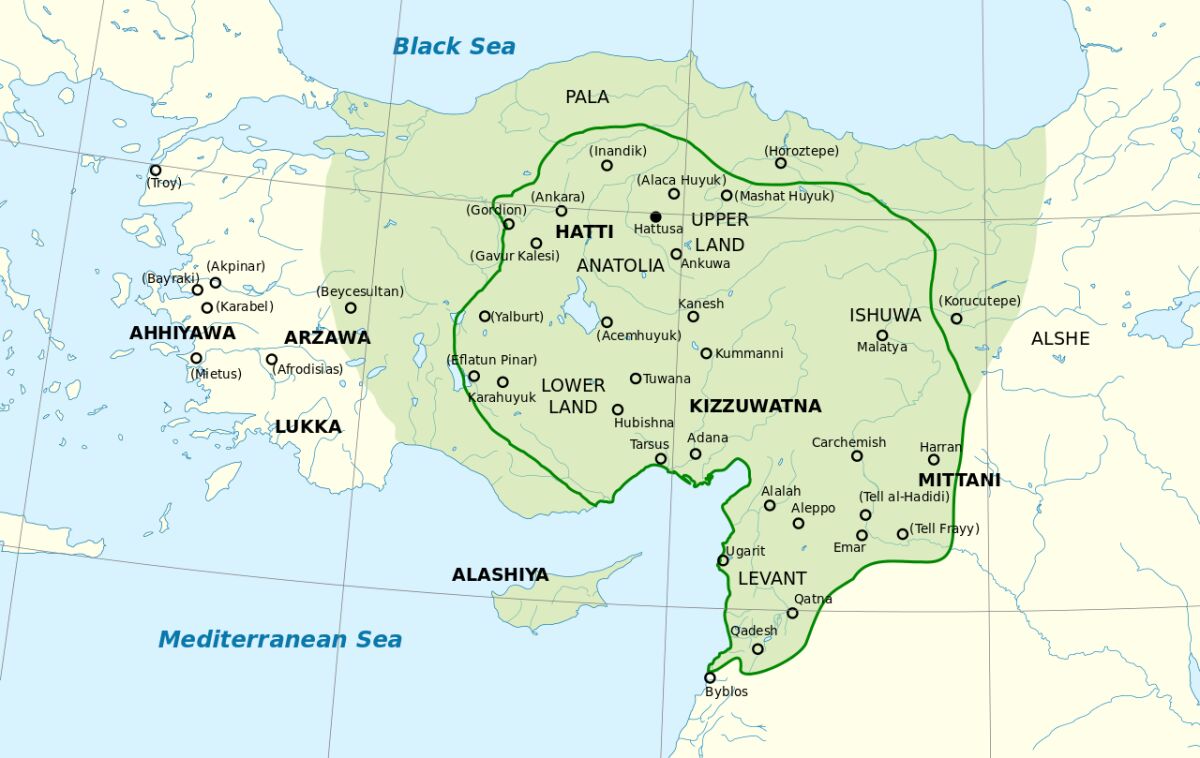

As highlighted in our cover article for this magazine (“Finding the Hittites”), present scholarship has reconciled with the fact that the Hittites, as a major ancient entity described in the Bible, did in fact exist. Now, however, a relatively common charge is that the biblical Hittites are, at the very least, anachronistic—that the biblical Hittites of the second millennium b.c.e. (particularly of the patriarchal period) are not accurate representations but rather retrojections of the later Syro-Hittite states (or “Neo-Hittites”) of the first millennium b.c.e.

This is based, in part, on the hypothetical assumption that the Torah was not written and compiled as traditionally ascribed to Moses, but nearly 1,000 years later (closer to the middle part of the first millennium b.c.e.)—a popular minimalist compositional theory known as the Documentary Hypothesis. (The same reasoning also applies to the books of Joshua and Judges, and their own Hittite references.) This assumes that much later biblical authors (or perhaps more appropriately, forgers) could not have known the political situation of the Hittites during the second millennium b.c.e. and thus were retrojecting the geopolitical situation of the later Syro-Hittites onto this earlier history. Essentially claiming that the sweep of biblical Hittite history between Genesis and Judges constitutes a falsified representation for narrative or ideological purposes.

Does this theory hold water?

‘Conspicuous Paucity’

In 2016, Biblical Archaeology Review published a staff article titled “The Hittites: Between Tradition and History.” It stated: “Archaeology tells us a lot about the Hittites …. But it’s hard to reconcile this with the Hittites of the Bible. …

To a certain extent, the composition history of the Pentateuch may be relevant to this discussion. If one were to assume that these narratives depict historical realities that were written down close to the time of occurrence, then one might conclude that the references are to the original Hittites rather than the Neo-Hittites. However, the majority of scholars believe that these narratives were composed hundreds of years after the events that they describe and often contain anachronisms for the time of composition superimposed on the narrative time. This would suggest that the references reflect the Neo-Hittites.

Part and parcel of this is the opinion that the Hittites during the second millennium b.c.e. did not really have a presence as far south in Canaan as the Bible describes for this period.

In his 2006 article “The Hittites and the Bible Revisited,” the late Prof. Itamar Singer concluded that “the archaeological evidence seems hardly sufficient to prove a presence of northern Hittites in Palestine [during the second millennium b.c.e.]. After a century of intensive excavations, all that has surfaced is a handful of Hittite seals and about a dozen pottery vessels that exhibit some northern artistic influences. The seals may have belonged to Hittite citizens who passed through Canaan …. The paucity of tangible evidence becomes even more conspicuous in the face of the absence of two salient features of Hittite culture—the hieroglyphic script and the cremation burial—both of which seem to have extended only as far south as the region of Hama in central Syria.”

Is it a fair assessment? Is the idea of Hittites living deep in the Levant—as far south as Canaan—anachronistic for the second millennium b.c.e.?

This whole debate appears to be nothing more than a case of perspective—the proverbial “glass half empty” versus “glass half full.”

‘Relatively Numerous’

Amir Gilan, in his 2013 Biblische Notizen article “Hittites in Canaan? The Archaeological Evidence,” noted of the late second-millennium b.c.e. period: “Interestingly … compared to other regions of the Ancient Near East, Hittite finds in Palestine dating to the empire period are relatively numerous, as Hermann Genz’s recent comparative survey has shown. Hittite objects were only rarely found outside central Anatolia, and such artifacts usually belong to the realm of diplomacy rather than trade” (emphasis added throughout). Gilan proceeded to list numerous Hittite archaeological discoveries found throughout the Southern Levant, dating to the second half of the second millennium b.c.e.—the Hittite New Kingdom period.

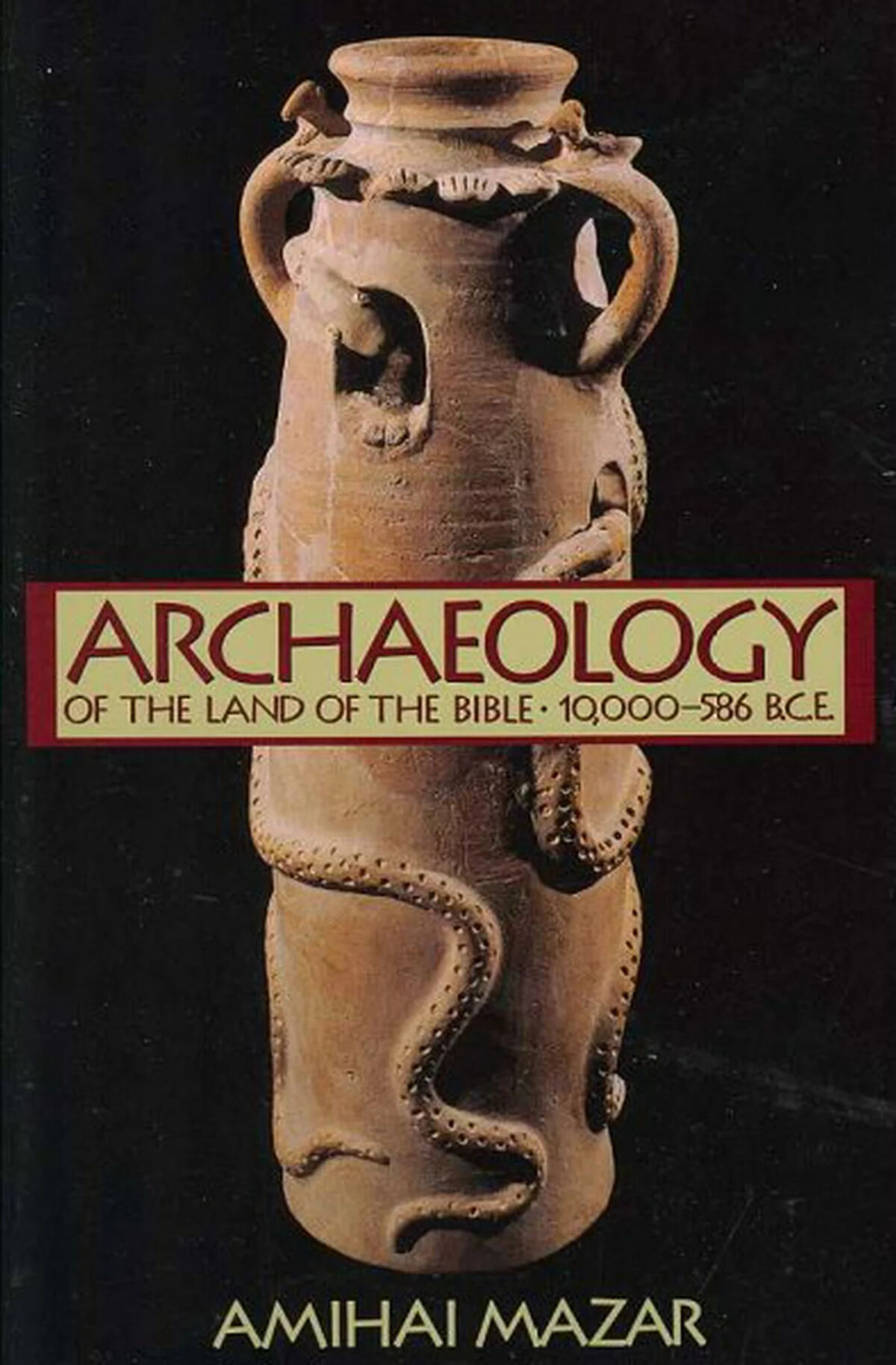

Prof. Amihai Mazar likewise notes several such discoveries in Canaan in his comprehensive 1990 book Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 B.C.E.—going back as far as the Old Kingdom period. For example, a “silver pendant found at Shiloh was decorated with the symbol of the weather god, well-known from Anatolia. This pendant indicates relations with the Hittite culture of Anatolia during that time,” deep in the heart of Middle Bronze Age Canaan.

In light of Singer’s reference to an absence of Hittite-style cremation burials, it is interesting to note Larry Herr’s 1976 Amman Airport excavations, in which a mortuary building, used for adult cremation, was uncovered. This structure dated to the empire period and was identified by the excavator as the product of Hittite influence into this southern area. “The practice of cremation was unknown among the Canaanites, yet it was practiced by Indo-Europeans—among them Hittites, some of whom may have settled in Transjordan,” Professor Mazar writes of Herr’s discoveries. He calls it a sign of “demographic heterogeneity.” “[I]f correctly interpreted, [this] is unique evidence for the practice of cremation in the LB period in Palestine. It may indicate the presence of some Indo-Europeans (Hittites?) in this part of the country.”

The late Prof. Aharon Kempinski also tackled this question. In his 1979 Biblical Archaeology Review article “Hittites in the Bible: What Does Archaeology Say?”, he highlighted a laundry list of Hittite artifacts and architectural elements throughout Canaan during both the Old and New Kingdom periods. “Two Hittite jugs imported from the center of the Anatolian plateau were found in a Megiddo tomb dating from about 1650 b.c.e. [the start of the Old Kingdom]. From the Late Bronze Age (1600 b.c.e.–1200 b.c.e.) archaeologists have found in Palestine hieroglyphic Hittite seals, Syro-Hittite ivories … and other objects … of Hittite or Syro-Hittite influence can also be seen in Palestinian architecture. An especially impressive example is the lions at the entrance to the Canaanite temple from Area H at Hazor …. The columns of the Hazor temple portico also demonstrate the strong influence which Syro-Hittite culture exerted on northern Palestine.”

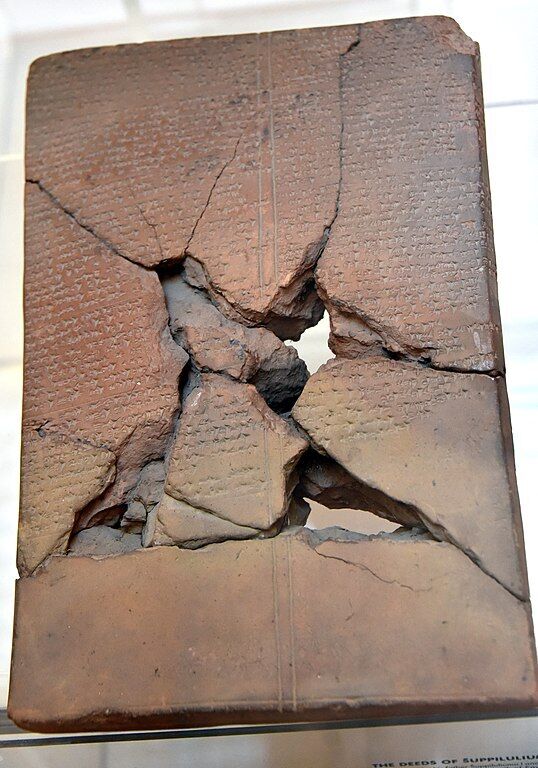

Kempinski also highlighted a peculiar Hittite document from the 14th century b.c.e., known as “The Deeds of Šuppiluliuma.” The document recounts how “formerly the storm-god took the people of Kurusutamma, sons of Hatti, and carried them to Egypt ….” (Compare with the Bible’s specific patriarchal period references to “sons of Heth” in Canaan.)

“Apparently, the Hittite people of Kurusutamma, a city in northern Anatolia near the Pontus Mountains, had resettled somewhere in Egypt as that term was understood by the Hittites,” Kempinski wrote. “For the Hittites, Egypt included all of the area under Egyptian rule, including Palestine and part of Syria. The Hittites from Kurusutamma may have resettled, then, in Palestine.” He noted that this explanation for the otherwise odd biblical appearance of early Hittites so far south in Canaan (i.e. in Hebron) at the time period of the patriarchs was first put forward by the “brilliant” Hittite scholar Emil Forrer in the 1930s. “Forrer’s suggestion was not widely accepted by scholars. In light of new evidence for Hittite settlement in Canaan … it now deserves to be reconsidered.”

Then there’s the redoubtable Archibald Henry Sayce, who as early as 1905 concluded—based on archaeological evidence (namely, “trichromatic Cappadocian ware” from Gezer)—the presence of Hittites in the Southern Levant as early as the 12th Dynasty of Egypt (20th–18th centuries b.c.e.).

Beware the ‘Inconclusiveness of Negative Testimony’

In light of such, even the possibility of such, is it just or necessary to conclude the biblical references to Hittites as far south as Canaan during the second millennium b.c.e. as confused or anachronistic—more bluntly, as wrong? Quite the contrary. Archaeology—which by its own limitations can only give us a minimal picture anyway—does speak evidentially to the presence of Hittite culture and influence deep within Canaan across the second millennium b.c.e.

It’s also worth pointing out that the Bible does not make out Canaan to be some veritable capital of the Hittite empire. Joshua 1:4 informs us that the main body of this polity was in the far north. Judges 1:26 also points to the separation of Israel from the Hittite heartland. It is likewise notable that, particularly during the patriarchal period, Hittites are described on a very individual basis as living within the territory of Canaan.

And as far as the general sweep of Hittite history in the Bible: The biblical text itself modulates for this Hittite polity, across the span of this second millennium and on into the first. Why, if it was a simple retrojection of the first millennium Syro/Neo-Hittites? Why the very specific use of the term “children of Heth” during only the early patriarchal period? Why the appropriate use of the name “Tidal,” and as a ruler of a gaggle of peoples? Why the consistent, later general references to Hittites during the kingdom period of the mid-to-late second millennium b.c.e.? And why is it only among the first millennium b.c.e. passages that we repeatedly read of “all the kings of the Hittites,” plural, fitting with the breakup into the many Syro-Hittite states of this period—and never before?

Of course, the answer should be obvious. But in the words of George Frederick Wright, in 1910, maybe we haven’t sufficiently learned the lesson that the discovery of the Hittite empire should have taught us: “When shall we learn the inconclusiveness of negative testimony?”