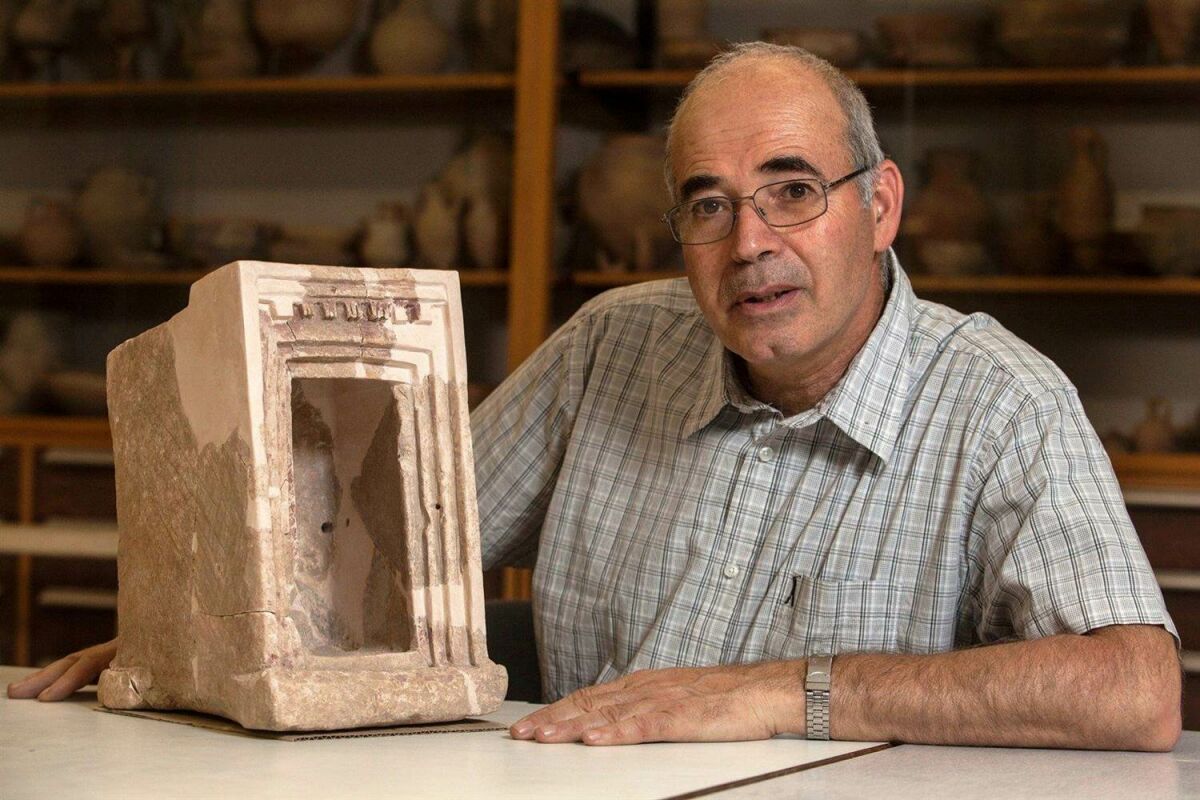

In May, Hebrew University Prof. Yosef Garfinkel published an academic article titled “Early City Planning in the Kingdom of Judah: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh 4, Tell en-Naṣbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara and Lachish V” in the university’s Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. The otherwise mundanely titled paper made a fascinating case for an early, core 10th-century b.c.e. kingdom of David (and later, Solomon and his son Rehoboam), made up of these interconnected cities, displaying several parallel construction features, material culture, and a similar dating range.

No sooner had the article emerged, before it was met with “reams of skepticism,” “howls of disapproval” and “colorful insults.”

Why?

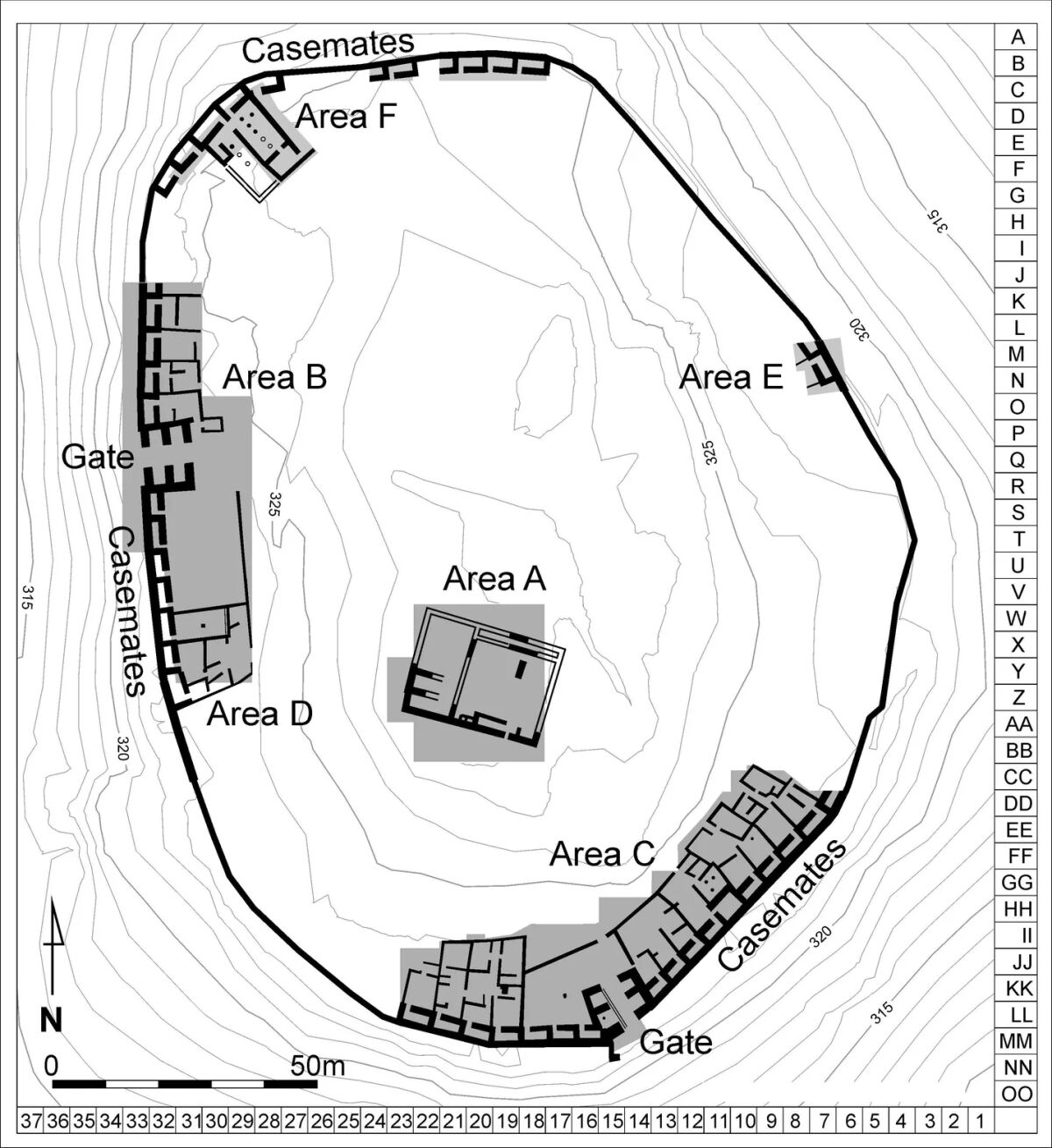

Case of the Casemates

While excavating Khirbet Qeiyafa between 2007–2013, Professor Garfinkel had been stunned to find evidence of a single-period site that was only in operation for a very brief 20 to 30 years and was radiocarbon dated squarely to the time of King David (the start of the 10th century b.c.e.). Armed with this knowledge, Professor Garfinkel used its closely confined, cleanly defined stratum to compare to a handful of other, more loosely-anchored regional sites that have been excavated over the past century. He re-examined finds from Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Nasbeh and Khirbet ed-Dawwara.

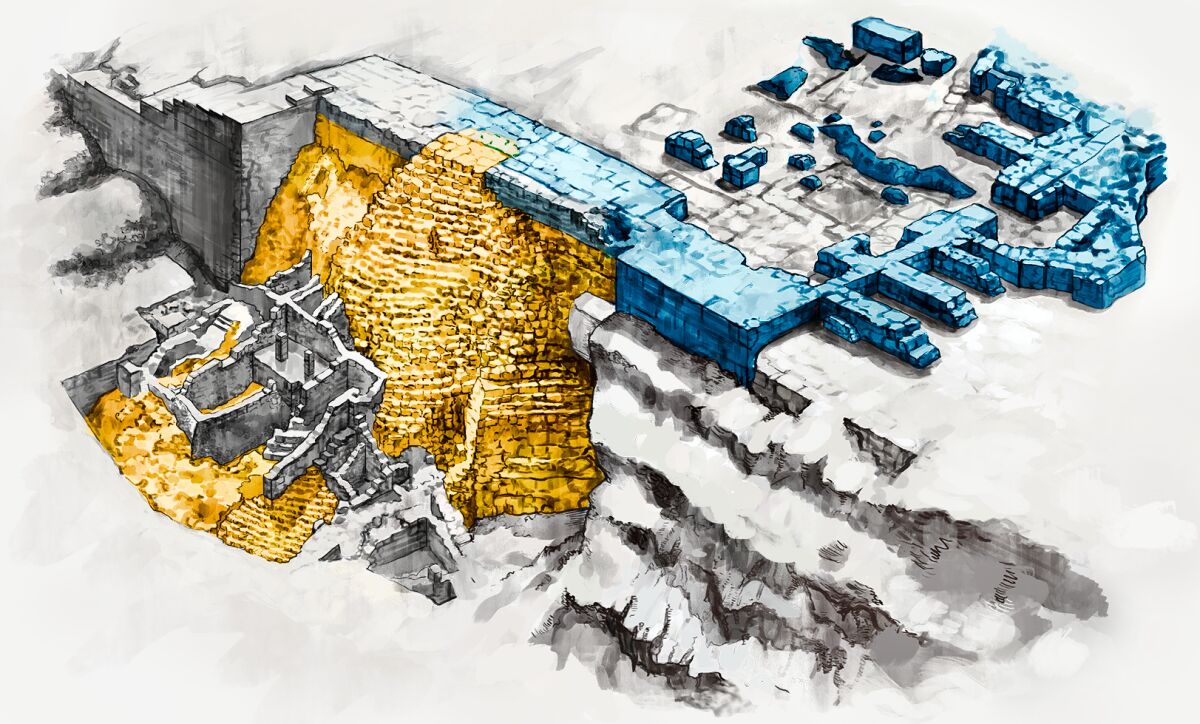

He identified in particular a unique, Judean-style casemate wall construction around these cities, with a peripheral belt of residential buildings attached to and incorporating the casemate walls, as well as an inner peripheral street. He also noted the parallel material cultures, logical geographical positioning of the cities in relation to one another, and a good fit in dating to within the early-mid 10th century b.c.e., especially in comparison to parallel material from Qeiyafa. As such, he argues that these cities are evidence of a core, pre-planned Davidic kingdom that emerged at the time, reflecting deliberate city planning across the region, and the expansion of the kingdom into the Shephelah (Judean lowlands) during the early 10th century b.c.e.

Toward the end of his article, Garfinkel highlighted his recent excavations at Lachish, a city which the Bible states David’s grandson Rehoboam fortified (2 Chronicles 11:9). After excavating the northeast corner of Lachish, his team discovered a new, previously unknown city wall. Through carbon dating they were able to narrow its construction window to the end of the 10th century and beginning of the ninth, synchronizing well with the biblical period of Rehoboam.

As is typical with such academic reports, Professor Garfinkel’s findings filtered through to the media. It was summarized on sites such as the Jerusalem Post, Ynetnews and Jewish News Syndicate. We featured the findings ourselves in a sit-down interview with Professor Garfinkel; evidently, a fairly popular discussion, with around 75,000 views. In the interview, Let the Stones Speak host Brent Nagtegaal asked: “Do you feel like there is going to be pushback from some archaeologists?” Garfinkel responded: “I’ve never worried about what other scholars might say.”

‘A Fish Story’

That same week, the Times of Israel published “Web of Biblical Cities Depicts King David as Major Ruler, Says Israeli Archaeologist.” The author, archaeology correspondent Melanie Lidman, did a good job outlining Garfinkel’s conclusions. She also highlighted a degree of emerging pushback, as hinted at in the subtitle: “Hebrew University professor claims evidence around Jerusalem supports David as no mere shepherd chieftain; critics accuse him of oversimplification, calling theory a fish story.” Lidman primarily cites Gath excavator Prof. Aren Maeir, who doesn’t necessarily believe that the cities were not “Davidic,” but simply that Professor Garfinkel’s conclusions are too speculative to be sure.

Maeir told the Times of Israel:

Once you start building a whole scenario of the size of the kingdom at various points, and they’re based on not clearly proved suppositions, you’re building a house of cards. … It’s like when a fisherman tells you about the type of fish he caught, and with each story, his arms get wider and wider. Is it a sardine, a mackerel or a blue whale? If you read the biblical text and take it literally, then it’s a blue whale. I think that probably there was a small kingdom in Jerusalem, but we don’t know the influence that this kingdom had.

Lidman’s article concluded (emphasis added throughout):

[Despite Garfinkel’s research] there is still little archaeological evidence of an organized monarchy from the assumed time of King David’s reign in the two places where he is recorded in the Bible as having spent the most time: Hebron and Jerusalem.

The story of King David has vexed experts for decades since so little evidence remains of the rule of the glorious and complicated biblical king. “I can take a shoebox and put inside everything we have from that period,” Yuval Gadot, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, told the New Yorker in 2020 about evidence in Jerusalem from King David’s reign.

Such a conclusion is deeply deceiving, however, because it depends entirely on whom, and about what, you ask. For several archaeologists, the most significant archaeological evidence for the power of King David’s reign comes precisely from Jerusalem, including monumental architecture unparalleled for this period anywhere in Israel. (See our article here for more detail. You can also read our response to Ruth Margalit’s rather extraordinary 2020 New Yorker piece, which made some waves based on the curious nature of the article.)

David Who?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the disagreement with Professor Garfinkel reached full maturation in Haaretz’s report by archaeology correspondent Ariel David. In his article “Israeli Archaeologist Claims He Has Found David’s Kingdom, but Fellow Researchers Cry Foul,” David wrote:

Garfinkel’s study … was greeted with reams of skepticism by many fellow archaeologists, who claim that his conclusions are based on assumptions and poorly interpreted data. … His study attempts to contradict the more broadly accepted paradigm that David and Solomon, if they were even historical figures, were local chieftains ruling over a tiny Jerusalem and not much more, and that Judah only emerged as its own as a kingdom a century or so after the supposed time of these monarchs.

Professor Garfinkel has written much on this so-called “broadly accepted paradigm”—namely, its collapse. You can read his popular article on the subject, “The Birth and Death of Biblical Minimalism,” on our website (first published over a decade ago). And as for doubting David’s very existence as a historical figure? This question has long been put to bed, particularly since the discovery of the Tel Dan Stele in 1993 (alongside two other potential inscriptions). This is no longer a topic of serious academic debate; it’s unequivocally not part of a “broadly accepted paradigm.”

Nonetheless, David goes on: “Garfinkel’s new research has been greeted with howls of disapproval since its publication. Several archaeologists contacted by Haaretz declined to comment on the record—but did produce some colorful insults.”

Two archaeologists did agree to go on record: Maeir and Prof. Israel Finkelstein, who has made a name for himself with his low chronology theory and dismissal of David as a “hillbilly,” “little more than [a] hill country chieftain.” (Still, even he does not call into question David’s very existence—his infamous book The Bible Unearthed states that the discovery of the Tel Dan Stele “change[d] forever the nature of the debate” about David, with its “dramatic evidence of the fame of the Davidic dynasty less than a hundred years after the reign of David’s son Solomon … clear evidence that the reputation of David was not a literary invention of a much later period.”)

Finkelstein, for his part, has previously made his position on Professor Garfinkel clear, telling the New Yorker, “When I sit in a conference abroad, and he goes onstage and says primitive things, I want to die from embarrassment.” About Garfinkel’s most recent academic article, Finkelstein told Haaretz, “I am not so sure that all the sites that he cites date to exactly the same phase in the 10th century b.c.e.”

Ariel David explained: “Precisely dating ancient remains is notoriously difficult, as even scientific methods like radiocarbon have significant margins of error.” This could be an otherwise conceivable objection. But recourse to significant radiocarbon margins of error in this case is a rather interesting line, given Finkelstein’s prior praise of the unbiased, “amazing” accuracy of radiocarbon dating—and also given that several of his own arguments for his revolutionary low chronology fall within radiocarbon margins of error. Nevertheless, the article continues: “[F]or example, the small settlement at Dawwara was probably established in the later part of the 10th century b.c.e., while Nasbeh and others are from earlier, according to Finkelstein, who for decades has been a leading voice of the skeptical camp in the debate on biblical historicity.”

David continued: “As far as the fortification at Lachish, it probably dates to the ninth century b.c.e., long after the supposed time of David, Solomon or even his son Rehoboam, Finkelstein adds. It’s also worth noting that the tradition of Rehoboam fortifying cities doesn’t appear in the book of Kings but only in Chronicles, which is considered by most biblical scholars to have been written many centuries later.” Naturally, because it was written centuries later, the book of Chronicles must also of necessity be wrong.

Maeir told Haaretz, “Yossi (Garfinkel) has a very black-and-white understanding of things and his interpretations often don’t recognize that situations can be more nuanced and complex …. There may have been multiple identity groups in the area [responsible for these constructions] that we know nothing about.”

This comment is particularly interesting, in light of some backstory. Following Garfinkel’s original declaration of Khirbet Qeiyafa as an early 10th-century b.c.e. Judahite site, the skeptical camp argued it must have belonged to the neighboring Philistines. This was aptly rebutted by the excavators. Then it was posited as a Canaanite site, which was likewise rebutted. Then that it was perhaps a northern Israelite, 11th-century “Saulide confederation” site. Now, the suggestion that such constructions could be the work of any one of “multiple identity groups in the area” that we as yet “know nothing about”? And the article goes one step further: “Prof. David Ussishkin has suggested [Khirbet Qeiyafa] may not have been a city at all, but a cultic compound,” David wrote.

Anything but Davidic, Judahite.

‘Politics of Conflict’

Politics were also dragged into the issue. The Haaretz piece continued: “As is often the case with archaeology in Israel, the argument [about David and his kingdom] is not confined to academic conferences, which are nevertheless the venue of some entertaining screaming matches, but frequently spills over into issues of nationalism and identity in the modern Jewish state, as well as the politics of its conflict with the Palestinians.”

I find this oft-repeated line of reasoning difficult to follow. This accusation against David is repeatedly brought up by Western media outlets. But why is the existence of David and his kingdom such a “political” issue in relation to the Palestinians? Why are later rulers of Jerusalem and Judah not a political issue (of whom the same Haaretz author says “[t]here is no question” their kingdom existed, with a “capital in Jerusalem”)?

I would venture to suggest the opposite—that this dismissal of David’s existence, and the significance of his kingdom, would be far more inflammatory toward Palestinians. Why? Because it rubbishes Islamic scripture. Numerous passages in the Qur’an address and even praise David and Solomon, and the power of their kingdom. “And Allah blessed David with kingship and wisdom” (Al-Baqarah 2:251). “Indeed, we granted David a great privilege from us …. And to Solomon … they made for him whatever he desired of sanctuaries, statues, basins as large as reservoirs” (Saba 34:10-13). “[R]emember our servant, David, the man of strength …. We strengthened his kingship …. We instructed him: ‘O David! We have surely made you an authority in the land’” (Sad 38:17, 20, 26).

Another passage in the Qur’an describes an incident at David’s palace and includes a similar detail to one contained in the biblical account, a detail highlighted by Dr. Eilat Mazar in pinpointing the location of his palace (read more about this in our article “Jerusalem Archaeology, Muslim History and the Mazar Excavations”).

I wonder why those in the Western media who are so quick to dismiss King David think they are appealing to Palestinian sensibilities? Is this not rather espousing kufr?

‘So Long, David’s Empire’

The Haaretz article concluded boldly, under a less-than-subtle subhead, titled “So Long, David’s Empire”:

Ultimately, whether or not Garfinkel’s theory holds up, its very existence is perhaps a sign of the success of the critical approach to the Bible’s historicity. When a longtime supporter of the more traditional view acknowledges that there is no evidence for the united monarchy and that, at best, David ruled over a tiny kingdom, it might be time to declare this debate over and done.

“Even if Garfinkel is correct, he does not change the overall picture significantly as he himself is not speaking about a Davidic empire,” Finkelstein notes. “He went on a crusade to show that there was a Davidic empire and ended up admitting that there may have been a Judahite limited territorial entity, meaning that he too has joined the critical camp on biblical history.”

Professor Garfinkel, a “longtime supporter” of the traditional view? Hardly. He was originally a prehistorian with no skin in this game, who only found himself embroiled in the “David” controversy following the results of his Qeiyafa excavation in the late 2000s. (His outsider status is one of the things that actually makes him perfect for this debate.)

To conclude that he acknowledges that “at best, David ruled over a tiny kingdom”? This is somewhat contradictory, given at the very start of the article, Ariel David introduced Garfinkel’s belief as one that “David controlled a relatively substantial territory.” And furthermore Garfinkel’s paper does not seek to constrict the boundaries of David’s kingdom; rather, as the Haaretz article itself cites, it simply presents “the urban core of the kingdom of David.”

To say “it might be time to declare this debate over and done” is now a tired refrain that has been repeated numerous times over the decades, by both sides of the debate. Yet for those who have followed this debate, Finkelstein’s own concluding statement here belies the degree to which the paradigm has shifted away from the hyper-critical camp of the 1980s and ’90s.

Certainly, Garfinkel’s rather reserved article, highlighting four cities (plus a later fifth), is in no sense “maximalist.” Still, the overall reaction to it was striking: “howls of disapproval,” “colorful insults,” “reams of skepticism,” “crying foul.” It was likened to “a fish story,” “a house of cards,” a “problematic” article based on “assumptions,” “suppositions,” “oversimplification,” “lack of nuance” and “poorly interpreted data.” According to such criticism, Professor Garfinkel’s early 10th-century cities should be redated earlier than David, and late 10th-century cities should be redated later than Rehoboam. Nothing can be allowed to fit securely within Garfinkel’s allotted timeline; certainly nothing with the biblical account.

So, so long, David’s empire. Debate “over and done.”

From Whence Comes ‘Such Obloquy’?

Such criticism is reminiscent of the pushback the late Jerusalem archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar received after publishing her impressive Davidic- and Solomonic-era remains in Jerusalem. The opposition was so intense that the late Biblical Archaeology Review founder and editor Hershel Shanks felt compelled to write “First Person: In Defense of Eilat Mazar” in 2008:

No one would question [Eilat’s] professional competence as an archaeologist. Her chief sin, however, is that she is interested in what archaeology can tell us about the Bible. But that is not the worst of it. She is willing to make suggestions that are plausible, even likely, but are nonetheless not 100 percent certain. (Few archaeological conclusions are.) …

Eilat Mazar had the temerity to suggest that this building might be King David’s palace. Her report in bar considered various other possibilities and concluded that “[t]he biblical evidence, I submit, better explains the archaeology we have uncovered than any other hypothesis that has been put forward.”

Several high-toned, condescending scholars have been derisive—largely, I believe, because Eilat Mazar dares to address a matter that is so important and meaningful to lay persons all over the world, instead of something of special interest to a handful of scholars. … What she is guilty of is making a reasonable judgment about archaeological evidence as it relates to the Bible. In some scholarly circles, however, this is considered “unscholarly.” If the judgment she made related to something other than the Bible, no one would give it a second thought. Only a finding related to the Bible brings such obloquy down on the head of a leading archaeologist.

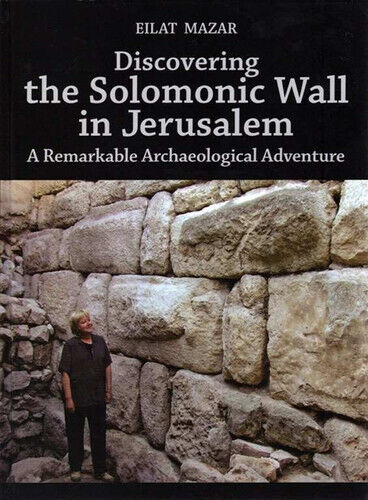

Dr. Mazar herself alluded to the strange situation she found herself in, in her 2011 book Discovering the Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem (pages 98-99; relating here to her 10th-century finds north of the City of David, on the Ophel):

I was amazed at how easily our findings at the Ophel were dismissed. … [T]hey still pointed to the existence of a sophisticated, impressively built complex situated in a prominent, strategic location of Jerusalem, and from a time believed by various scholars in which either nothing of great importance was constructed in the city—which they do not even recognize as a city!—or nothing could have survived. …

It was difficult to understand how one could ignore the significance of the discoveries from the Ophel, which, it should be noted, had been published in both academic and popular journals—and especially since they pointed to a relatively early date for royal construction in biblical period Jerusalem. Something like this should have called for further evaluation, specifically in articles and conferences concentrated on the time frame in question. Since I felt the need to remind both my colleagues and the general public of these remarkable finds, in 2003, I wrote an article (published in 2006) in which I once again presented the remains …. Still, none of the publications attracted the needed attention.

A rather condemning reason for this lack of attention was provided by Prof. Douglas Petrovich, in his tribute to Dr. Mazar following her untimely death in 2021. He related the following story:

When I was a Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto, I was among a number of students and faculty members who attended a monthly Israel interest group meeting. … In 2011, our focus was on the alleged united monarchy. The group’s leader … assigned readings purely from critical scholars and a couple of archaeologists with a low view of biblical historicity. After viewing the reading list before our meetings began, I contacted him and asked why Mazar’s volume on the Solomonic fortifications and her volume on the Large Stone Structure were not part of the reading list. After all, Mazar’s claims were monumental, and it behooved a serious study group to look into these claims with great interest and detail, in order to substantiate or reject them intelligently and objectively. His reply simply was that books by Eilat Mazar are not necessary because her work is motivated by political objectives. He offered no evidence for such an accusation, and we never discussed her findings within our group. This unprofessional response by a scholar who should know better is a perfect example of what an archaeologist faces when he or she attempts to connect monumental architecture or material finds with elements in the biblical narrative. Mazar’s stance was heroic.

Given the degree of veritable censorship, perhaps it should be no surprise after all to find the regular, now-dated refrain repeated so often in journalism (as in the above Times of Israel article): There is still little archaeological evidence of an organized monarchy from the assumed time of King David’s reign in Jerusalem. Only a shoebox-worth of remains.

What is it about the period of David and Solomon (10th century b.c.e.) that “brings such obloquy down on the head of a leading archaeologist”? You may have your own theories. Nevertheless, the spirit behind such a reaction is certainly reminiscent of the biblical account of the very breakup of the united monarchy of Israel itself, with the split from the tribe of Judah. “What portion have we in David? Neither have we inheritance in the son of Jesse; to your tents, O Israel; now see to thine own house, David” (1 Kings 12:16). Three-thousand years on, the sentiment holds just as true to this day.

Professor Garfinkel, meanwhile, remains positive, looking toward his next project, and particularly enthused about developments at Lachish. “I’ve never worried about what other scholars might say,” he stated. “I am always saying, ‘We have fresh data. They have a collapsed theory.’”