In times of war, for a nation to be truly victorious, it must believe in itself and its moral standing. It must have pride and confidence in its history, something that binds its people together. That national history, in turn, helps provide a vision of its destiny.

Our website is dedicated to history and archaeology—specifically, biblical history and archaeology—something that in large part relates to the history of Israel. We examine archaeological evidence relating to the historicity of the biblical account. We take a positive view of Bible historicity, agreeing with Sir Winston Churchill that the evidence at hand “fortif[ies] the grand simplicity and essential accuracy of the recorded truths which have lighted so far the pilgrimage of man” (Thoughts and Adventures, “Moses: The Leader of a People”).

We agree with the renowned 20th-century archaeologist Prof. Nelson Glueck, who wrote, “It may be stated categorically that no archaeological discovery has ever controverted a biblical reference. Scores of archaeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or exact detail historical statements in the Bible” (Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev; see here, here and here for some examples of supposed contradiction). We agree with his contemporary Prof. William Foxwell Albright, who wrote, “There can be no doubt that archaeology has confirmed the substantial historicity of Old Testament tradition” (Archaeology and the Religions of Israel). He also wrote, “Discovery after discovery has established the accuracy of innumerable details of the Bible as a source of history” (The Archaeology of Palestine).

Naturally, such a positive position on Bible historicity is not ubiquitous. There are numerous differing opinions on the accuracy and correct interpretation of the biblical account in scholarship. But it goes without saying that the question of the faithfulness in which the biblical text has been relayed to us is no moot matter. The Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, is dear to the hearts of millions of Israelis and Jews, as well as billions of believers worldwide: to Christians, who believe that “the Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God” (Romans 3:2; English Standard Version); to Muslims also, whose Qur’an repeatedly asserts that Allah “did reveal the Torah, wherein is guidance and a light” (Al-Ma’idah 5:44; Pickthall translation); and to numerous others of various religious persuasions besides.

Amid the horrifying events of the past two months, much of the online debate about biblical historicity appears to have gone comparatively quiet. Perhaps not surprisingly. Nobody has an appetite for such content at a time of national desperation. Now is the time for heroes and heroism, not for—as the great wartime leader Churchill said—the speculative and sapping “tomes” of “Dr. Dryasdust” and “Professor Gradgrind.” “We reject, however, with scorn all [their] learned and labored myths that Moses was but a legendary figure,” wrote Churchill.

Now is a time for anchoring to, and drawing from, the bedrock of heroes and their lessons of old—lessons that mere negative testimony cannot do away with. (As Prof. George Frederick Wright wrote in 1910, following the about-face in scholarship after the discovery of the Hittite Empire: “When shall we learn the inconclusiveness of negative testimony?”) Dismissiveness is a luxury afforded only by peacetime.

During such a time of national calamity, and in light of this study of history and academia, lessons from 1940 France come to mind.

The ‘Strange Defeat’

Before World War ii, France was purported to have the strongest military in the world. Adolf Hitler had assumed that conquering the nation, while achievable, would be an uphill battle, perhaps costing around 1 million German lives and perhaps requiring a number of years to fully achieve. Yet to everyone’s surprise, France fell within 46 days, with the invasion costing the lives of only 27,000 German troops. It was one of the most stunning and rapid national defeats in history (so stunning that Hitler initially became terrified that his forces must have fallen into some kind of intentional, elaborate trap). In the words of historian Barrie Pitt, it was a “military catastrophe … that has no equal in the history of war.”

How did it happen?

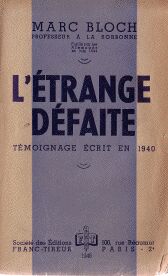

The first and foremost to pen a detailed explanation was Frenchman, soldier and historian Prof. Marc Bloch. The very same year France was defeated, he wrote L’Étrange Défaite (The Strange Defeat); it was later published in 1946—two years after his own torture and execution by the Gestapo. In his three-chapter book, Bloch outlined the history leading up to France’s defeat, the failings on the part of the French leadership, failings on the part of the military, and failings on the part of its allies. Finally—and most intriguingly—he spent the final chapter in introspection. Titled “A Frenchman Examines His Conscience,” he focused on the general institutional and societal failings of interwar France that had made her ripe for conquest.

“[H]ere I find myself coming to grips with an entirely different order of problems which belong, strictly, to the world of thought,” Bloch wrote. “It was not only in the field that intellectual causes lay at the root of our defeat. As a nation we had been content with incomplete knowledge and imperfectly thought-out ideas. Such an attitude is not a good preparation for military success.” He then described “a whole literature of renunciation. … The theme was purely academic, or it would be truer to say, childish.”

He proceeded to condemn the French system of higher education, including a focus on his own field—the teaching of history: “As a historian, I am naturally inclined to be especially hard on the teaching of history. It is not only the staff [military] college that equips its pupils inadequately to face the test of action.”

He further condemned a gutted morale and historical pride of Frenchmen at the time, writing:

There are two categories of Frenchmen who will never really grasp the significance of French history: those who refuse to thrill to the consecration of our kings at Rheims, and those who can read unmoved the account of the Festival of Federation. I do not care what may be the color of their politics today: Such a lack of response to the noblest uprushes of national enthusiasm is enough to condemn them. In the Popular Front—the real Popular Front of the masses, not the one exploited by the politicians—something lived again of the spirit that had moved men’s hearts on the Champ-de-Mars under the hot sun of 14 July 1790. Unfortunately, the men whose ancestors pledged their faith on the Altar of the Nation have lost contact with the profound realities of national greatness. It is no accident that our régime, in spite of all its democratic trappings, has never been able to create for the people of France festivals capable of sounding a note to the ears of all the world. We have left it to Hitler to revive the paeans of the ancient world.

“There is no getting away from the fact that we, the teachers, were largely to blame for this state of affairs,” Bloch wrote.

We had tongues and brains in our heads and pens in our hands. But we were all of us either specialists in the social sciences or workers in scientific laboratories, and maybe the very disciplines of those employments kept us, by a sort of fatalism, from embarking on individual action. We had grown used to seeing great impersonal forces at work in society as in nature. In the vast drag of these submarine swells, so cosmic as to seem irresistible, of what avail were the petty struggles of a few shipwrecked sailors? …

The fact remains that we are now in a position to measure up the results. … [O]ur leaders not only let themselves be beaten, but too soon decided that it was perfectly natural that they should be beaten. By laying down their arms before there was any real necessity for them to do so, they have assured the triumph of a faction.

Interwar France, “desperately tired” after World War i, had become so hollowed out in national pride and will that defeat, even at the hands of a statistically weaker (yet prouder) enemy, became inevitable. Bloch saw an intellectualism proverbially straining at a gnat and swallowing a camel—a highly educated and hyperspecialized French academia, one which “pays a great deal of attention to the physiology of plants—and quite rightly, but it almost entirely neglects field botany”; one in which “historical teaching deliberately cut itself off from a wide field of vision and comparison.” He saw individuals who “never really grasp[ed] the significance of French history.”

“What we need is that the windows should be thrown wide open and the atmosphere of our classrooms thoroughly aired,” concluded Bloch. (Doesn’t that sentiment ring true—considering what we have seen from college and university campuses around the world over the past several weeks?)

Other testimonies have reached similar conclusions: Interwar, rudderless, anchor-less, guidance-less France had, in the trappings of peacetime, emptied out her will.

What I find especially fascinating—and dangerous—about such testimony summarizing pre-war French academia is that, when it comes to biblical archaeology, the school of minimalism actually draws from, and celebrates, interwar France as a model. One of the most recognizable figures of the Bible-critical movement in Israel said the following in a 2021 interview with the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research (emphasis added throughout):

I am very close in my academic life to France and to the French institutions. And France has always been the lighthouse in the methodology of history, especially in the 20th century. Especially starting, I would say, in the ’20s, ’30s of the 20th century. And I take from the French three concepts of studying history, which I think are applicable to biblical studies and to the study of ancient Israel, including archaeology and ancient Israel. The first one, that is now very popular and we all use it, the idea of a longue durée …. The second concept, which I like very much when we speak about history, is again the French concept of histoire régressive. … Another, the third French concept … the very tricky and interesting expression, déconstruction positive, positive deconstruction …. I think that when one applies these three concepts of history, from the methodology of history point of view, one is on solid ground.

A colleague and Old Testament scholar at the Collège de France made similar statements in his 2018 École biblique et archéologique française lecture in Jerusalem: “The very good thing when you teach in the Collège de France is, you don’t teach any truths. You teach your ideas, and you see what happens. The French say, le savoir en train de se faire, ‘knowledge which is about to be constructed,’ and I think that’s a very nice idea …. I think this is the way that science should go on.”

Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, Dr. Igor Kreimerman and Dr. Peter Zilberg, however, lament the scene of modern critical scholarship in biblical archaeology (in language akin to that of Professor Bloch). “Today we are in a postmodern and deconstructive era,” they warn in their 2016 publication Debating Khirbet Qeiyafa. “Everything is relative, there is no right or wrong and contradictory approaches are all legitimate. Good scholarship, however, should be aware of the current trends and not get carried away by popular, but unsound, approaches. … Today, the methodology and basic worldview of biblical archaeology are under severe attack” (Chapter 5, “The Bible and Archaeology: Methodological Remarks”).

Cracks

Thankfully, modern-day Israel is not a mirror image of pre-1940 France. Israel’s mandatory national military service and reserve duty ensure that the country is not just one with “tongues and brains in our heads and pens in our hands,” unprepared for “embarking on individual action.” Commendably, part of that training includes visiting historical and archaeological sites within the country, learning about the history these troops are fighting for. On the whole, a recognition and respect for Jewish history and tradition appears far more widespread, rooted and engrained in the common man.

But it is at least hard not to see certain parallels. Parallels such as the infamous 2005 speech by Israel’s then-vice prime minister, who said, “We are tired of fighting. We are tired of being courageous. We are tired of winning. We are tired of defeating our enemies” (commenting, ironically, on what he saw as the “remarkable process” of Israel’s disengagement from the Gaza Strip). Or the comment made to me by my Hebrew teacher some years ago: We should just give up Jerusalem. All this fighting over this old city. What’s the point? What really is the point, if much of its rich and cherished history is only rooted in myth after all? Or the constant drip, drip, drip of demoralization and self-flagellation from outlets like Haaretz, both in news reporting and archaeology reporting.

Israel’s military might is superior to that of Hamas and Hezbollah. But as the lesson of 1940 France shows, war is not just about statistics on paper, but about will. And what we have seen from the past two months is a collective, impressive and commendable unification of Israel behind a cause—a will and purpose aptly summarized early on by Times of Israel journalist Haviv Rettig Gur, in his appropriately titled article “Hamas Does Not Yet Understand the Depth of Israeli Resolve.”

But one can’t help but see that the cracks are there. Certainly, they are deeper now than in Israel’s past (and have been vociferously manifested over the past year). Perhaps these cracks will not prove debilitating in the current war. But unless checked, they are certain to in the future. France’s Third Republic made it through four years of the First World War; it collapsed within six weeks of the second.

It should go without saying that none of these sentiments endorse Israeli pride, will and confidence in their biblical history against, or at the expense of, other peoples. As with Israel, the Arab peoples themselves have their own rich and shared Abrahamic history from which to draw on. Petty organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah, on the other hand, have no moral standing and no historical bedrock; they are merely shifting sands that will ultimately, by natural laws as sure as gravity, either be destroyed or destroy themselves. Anything built on a cult of hatred and death never lasts.

Over the past several weeks, it has been encouraging to see examples of Palestinians justly disassociating themselves from Hamas, as an organization with no qualms about killing its own people as well as Israelis. To see Bedouins seeking justice against this terrorist entity that has killed, maimed and abducted dozens of their own members. To see proud Druze soldiers supporting Israel’s war effort. To see those who reject the slander that the presence of Jews in the land is a mere modern colonial aberration, which must be extinguished. (Again from the Qur’an: “We verily did allot unto the Children of Israel a fixed abode”—Yunus 10:93.) To see those who reject the revisionist temple denial of the late Palestine Liberation Organization terrorist leader Yasser Arafat, but instead agree with the Supreme Muslim Counsel’s 1925 publication guide for the area of the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount: “Its identity with the site of Solomon’s temple is beyond dispute.”

The Arab peoples have a proud history found within the pages of the Bible and summarized in the words: “God was with Ishmael” (Genesis 21:20; Amplified Bible).

Who Will Tell This History?

History, they say, is written by the victors. This is true. But what is particularly fascinating about the Bible, and Israel’s history, is that it could be said to have been written in spite of the victors—in spite of the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Romans, Nazi Germany—anything and everything in between.

Israel’s history has been recorded in a book and in stone “so that for times to come it may be an everlasting witness” (Isaiah 30:8; International Standard Version). So that even when people do not, or cannot speak, the stones do (Habakkuk 2:11).

That history will survive moments such as these. The only question is how much today’s nation believes in itself, in its moral standing, as well as its historical foundations and future direction. How much pride and confidence does it have in the bedrock of its history?

Sir Winston Churchill is often quoted as saying of history, “The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward.” To this end, the field of biblical archaeology, when properly utilized, comes into its own. It provides such a necessary telescope—clarifying truths of old, and fostering a vision and national identity vital for success and victory in times of both war and peace.

Article updated 28/02/25.