Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

If the Garden of Eden is in Israel, then its entrance is Beth Shean—so said the third-century c.e. Rabbi Shimon Ben Lakish (Eruvin 19a). Indeed, the ancient city of Beth Shean stands in one of the most important and fertile junctions in all of Israel, between the Jordan and Jezreel valleys. The central mound of ancient Beth Shean is about 90 meters (300 feet) tall, making it the tallest archaeological tel in Israel. This site is located 27 kilometers (17 miles) south of the Sea of Galilee, in a well-watered region near a spring-fed stream that runs down the Harod Valley. The city stood over a major trade route that ran north along the Jordan River and connected Egypt and southern Canaan to Syria and Mesopotamia. Due to these factors, Beth Shean was an influential site throughout the ancient history of the Levant. Though its name means “house of tranquility,” Beth Shean’s history has been tumultuous.

In the biblical account, Israel failed to drive Canaanites out of Beth Shean due to fear of their chariots. The Philistines plastered King Saul’s dead body to the city’s walls after his defeat and suicide at Mount Gilboa. Solomon listed Beth Shean as one of the cities that provided goods for the king and his royal entourage. The city is also mentioned a handful of times in the New Testament. And the last century of archaeological excavations have provided some fascinating supplementary details about all of these accounts.

Founded by Canaanites

Many excavations have occurred at Beth Shean. Following World War i and the establishment of the British Mandate, European and American archaeologists flooded into the Levant, which had just become much easier to excavate. Beth Shean was the site of the first major excavation in the Near East after World War i. Famous archaeologists to excavate the site over the past century include Prof. Clarence Fisher, Egyptologist Alan Rowe, Prof. Gerald M. Fitzgerald, Frances W. James, Prof. Yigael Yadin, Shulamit Geva, and Prof. Amihai Mazar.

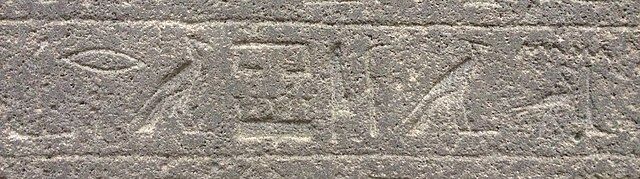

Evidence at the site of Beth Shean shows that it began to blossom as a Canaanite city during the Early Bronze Age iii (24th century b.c.e.). A few extra-biblical sources write about Beth Shean in the Canaanite period. Professor Mazar and archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni believe that the “Execration Texts,” or curse texts from Egypt, refer to Beth Shean (19th century b.c.e.—though the translation is disputed). Further, Thutmose iii listed Beth Shean among other Canaanite cities on his temple walls at Karnak (no. 110; 15th century b.c.e.).

The 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna letters also mention Beth Shean. Amarna letter EA 289 was written by Abdi-Heba, governor of Jerusalem, to the pharaoh of Egypt (Akhenaten). In line 24 of the text, he mentioned the “garrison of Bitsanu.” These letters, in content and chronology (describing a terrifying “conquest” of the Canaanite lands by a people called “Habiru”), fit well with the biblical account of the Hebrews’ conquest of the Promised Land circa 1400 b.c.e. and on into the 14th century (see here for more detail on this subject).

Archaeological features of the site have provided some insight into Beth Shean during this Canaanite period. Professor Mazar uncovered a temple that dates to the Late Bronze Age ia (16th–15th centuries b.c.e.). This temple resembles other Canaanite asymmetrical temples that have been excavated at Lachish, Tel Mevorakh and Tell Qasile.

Joshua 17 and Judges 1 document that Israel failed to drive the Canaanites out of Beth Shean. Joshua 17:16 records the tribes of Joseph lamenting that “all the Canaanites that dwell in the land of the valley have chariots of iron, both they who are in Beth-Shean and its towns, and they who are in the valley of Jezreel.” Despite Joshua’s encouragement in verse 18, Judges 1:27 records that “Manasseh did not drive out the inhabitants of Beth-Shean and its towns … but the Canaanites were resolved to dwell in that land.” In an article titled “Who Are the Habiru of the Amarna Letters?”, Prof. Douglas Waterhouse wrote that the broad plains surrounding Beth Shean would have been the perfect setting for the Canaanites to utilize these chariots. (For more on Canaanite chariots, read Iron Chariots: A Biblical Impossibility?)

Ruled by Egyptians

Israel did not have the strength or the will to conquer Beth Shean during the early judges period—but Egypt did. Sometime early on in the period of the judges (second half of the second millennium b.c.e.), Egypt trounced the local Canaanite defenses of the city and established Beth Shean as an Egyptian garrison.

“One of the major questions regarding the history of the site is why the Egyptians of the New Kingdom chose Beth-Shean as a garrison town and when this happened,” writes Prof. Amihai Mazar, who suggests a few reasons why Egypt chose to invest so much into Beth Shean as a garrison city. First and most importantly, Beth Shean was in an excellent geographic location. As mentioned above, the tel commanded broad plains and overlooked the vital junction between the Jordan and Jezreel valleys. Egyptian soldiers in Beth Shean could swiftly counter a threat in either location. Professor Mazar argues that textual and archaeological evidence indicates that Egypt captured Beth Shean under the 18th Dynasty of Egypt and that the city served as a garrison “for over 300 years.”

In the 13th century b.c.e, the 19th Dynasty of Egypt ruled over Beth Shean. This dynasty began with Seti i (who reigned from 1294 to 1279 b.c.e). In Beth Shean, Seti i constructed a new temple, a new dwelling quarter of the city, and new administrative buildings. Seti i also left behind a few monumental stelae (discovered in secondary use). The temple was made out of Canaanite materials but in the Egyptian style. This temple would remain in use, with some variations, on into the 12th century.

One stele discovered from Seti i is called the “Large Stele” and is considered the most impressive find from Egypt’s rule over Canaan. A second stele of Seti i describes him quelling an uprising by the Habiru, who were a thorn in Egypt’s side in Canaan for about a century before this time. (For more on the topic of the Habiru and their parallels with the biblical Hebrews, see here.) Seti’s son, Ramesses ii, also left behind a stele of his own, along with many other artifacts, including scarabs, amulets and clay figurines typical of the 13th century b.c.e.

During the early part of the 12th century b.c.e., under the 20th Dynasty of Egypt, massive government buildings were constructed in the northern part of the town. These structures were unquestionably Egyptian in style. One of these structures, according to Mazar, “was designed to impress visitors and reflect Egyptian rule and power.” The 20th Dynasty era yielded “the largest collection of Egyptian monuments and inscriptions ever found in the Asiatic [i.e. Levantine] provinces of Egypt” (“The Egyptian Garrison Town at Beth-Shean,” Amihai Mazar). Other discoveries, including copper from the Timna mines and silver from Turkey and Greece, indicate that Beth Shean was very active in commerce. Stone weights discovered at the site show that the locals used Egyptian measurements.

All of these facts show that Beth Shean had a mixed populace. Egypt dominated Beth Shean, yet many facets of the city remained Canaanite. The archaeological evidence indicates that Egyptian administrators and soldiers would have lived alongside the common Canaanites in this period.

Canaanite, Midianite, or Philistine Overthrow?

The Egypt’s 20th Dynasty began to lose its grip in Canaan during the mid-to-late 12th century b.c.e. Between the reigns of Ramesses iv and Ramesses vi, Beth Shean was violently ravaged. Mazar suspects that the city was destroyed by local Canaanites from neighboring cities like Rehov or Pehal, but it also could have been overrun by semi-nomadic raiders from the east (i.e. the Midianites). Others have suggested that it was the Philistines who overthrew Egyptian Beth-Shean.

The story of Gideon seems to occur shortly before the listed date of this destruction. Judges 7 records Gideon’s story. Verse 12 says, “Now the Midianites and the Amalekites and all the children of the east lay along in the (Jordan) valley like locusts for multitude ….” It is probably safe to infer that such a multitude would have had incursions with Beth Shean, which commanded the northern part of the Jordan Valley. Professor Mazar notes the possibility of this theory, saying that “the Midianite invasion and Gideon’s response are one possibility for the identification of the attackers.” As the story tells, Gideon drove out these Midianites and killed their princes. (For a full rundown of the archaeological evidence for the biblical account of Gideon, see our article here.) The judgeship of Gideon is generally dated to the late 12th century b.c.e., and Professor Mazar dates the reconstruction of a previously destroyed temple within the city to the end of that period, circa 1100 b.c.e. (“Beth Shean in the Iron Age: Preliminary Report and Conclusions of the 1990–1991 Excavations”).

There is another interesting Philistine connection to the ensuing time period. 1 Chronicles 10 and 1 Samuel 31 record that sometime near the end of Saul’s reign (at the end of the 11th century b.c.e.), the Philistine armies set up camp in Shunem, in preparation for a battle with Israel. Saul’s Israelite army encamped at Gilboa, from which he visited the witch at Endor to see if he would win the upcoming battle. Her divination revealed that Saul and his sons would all perish in the battle.

Though his sons died fighting at Gilboa, Saul committed suicide after being struck by an arrow. The Philistines collected the bodies of Saul and his sons and published their death throughout the region. 1 Samuel 31:10 records that the Philistines put Saul’s “armour in the house of Ashtaroth; and they fastened his body to the wall of Beth-Shan.”

This episode seemingly indicates that the Philistines ruled over Beth Shean. However, archaeological excavations have shown no sign of the Philistines living within Beth Shean during this period. Professor Mazar wrote of Beth Shean’s populace at this time: “The finds from this period contain no traces of Philistine presence in the town, and it appears that the Biblical account of the death of Saul at best relates to a historical event in which the Philistine forces carried out a military campaign from Philistia to the Gilboa and the Beth-Shean Valley, but never occupied this region for any length of time” (“Four Thousand Years of History at Tel Beth-Shean: An Account of the Renewed Excavations”). It appears the body of the Beth Shean population remained Canaanite throughout this time.

Upon hearing of the death of Saul and his sons, and of the desecration of their bodies, the Bible relates that men of Jabesh-Gilead traveled through the night and lowered them from the walls of Beth Shean, returning home and then cremating and burying the former royals. The Bible calls these men “valiant.” This epithet is usually ascribed to men of war in the Bible, implying that their mission was a dangerous one.

Whoever ruled Beth Shean was evidently not Israel’s friend—a status they would soon regret.

Annexed by David

1 Kings 4 lists 12 districts in 10th-century b.c.e. Israel that were expected to provide one month’s provisions each for King Solomon and his court. Verse 12 shows that an Israelite administrator, Baana the son of Ahilud, ruled Beth Shean. If Beth Shean was not under Israelite dominion at the death of Saul, but it was managed by Israelites in the early (and peaceful) reign of Solomon, then it was logically conquered by David.

This supposition aligns with facts about David’s conquests in 2 Samuel 8. Verse 1 records that David smote and subdued the Philistines. David then subjugated the Moabites, Arameans, Ammonites, Amalekites and Edomites. He secured his borders north of Damascus—further than the Israelite kingdom had ever expanded. “… And the Lord gave victory to David whithersoever he went. And David reigned over all Israel …” (verses 14-15). Based on this account, it is evident that David conquered Beth Shean as well, as it was allotted to Israel originally.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, evidence shows that Beth Shean grew extensively under David and Solomon. Three massive public buildings were built, described by Prof. Amihai Mazar as having “wide walls, their foundations made of large basalt boulders, with thick wooden beams above the stones supporting mudbrick superstructures” (from “The Beth Shean Valley and its Vicinity in the 10th Century b.c.e.”). One of these buildings has been characterized as a “fortress.” These structures were built around a new and improved gate structure. The new Israelite rulers understood the vital geographic importance of Beth Shean and fortified it accordingly, just as the Egyptians had done before.

Professor Mazar wrote: “It may be assumed that … some Israelite families from the hill country settled in the city alongside the locals and that Israelite religious beliefs and ideology were slowly accepted by the local population ….” Whatever the status of the population, these public structures indicate that Beth Shean was under a wealthy centralized government, which is precisely how the Bible describes Israel under David and Solomon. Beth Shean would remain in Israelite hands for a few hundred years, but its peak was under the reign of kings David and Solomon.

The Egyptian Empire Strikes Back

The kingdom of Israel was enervated after the death of Solomon, and the northern 10 tribes split from the house of David. In the fifth year of King Rehoboam of Judah, the Bible records that an Egyptian pharaoh named Shishak besieged Jerusalem and carried away the treasures left by Solomon. Shishak’s actions are recorded in 1 Kings 14 and 2 Chronicles 12.

The Bible does not specifically say that Shishak (identified as Pharaoh Shoshenq i) went beyond Jerusalem to the lands of northern Israel—but archaeology does attest to this fact. Shoshenq i lists Beth Shean as a conquered city on his temple reliefs at Karnak. Secondly, on the eastern side of Tel Beth Shean are the burnt ruins of an Israelite fortress which evidently stood for only a brief period of time.

Though the Egyptians did not linger in Beth Shean this time, their campaign left the city devastated. The massive gate structure of the city, as well as its three adjacent public and administrative buildings (constructed under David or Solomon), was obliterated. Beth Shean would not be rebuilt to its former glory under the northern kingdom of Israel. Professor Mazar wrote that the site would undergo some rebuilding in several small phases, as evidenced by “a jumble of fragmentary, poorly preserved walls”—yet would not reach the heights of power that it once exhibited.

2 Kings 15:29 records that in the days of King Pekah of Israel, Tiglath-Pileser of Assyria came and captured a swath of Israelite cities. The Bible lists the entire regions of Galilee, Gilead, and Naphtali. Professor Mazar dated Beth Shean’s subsequent destruction layer to this invasion by Tiglath-Pileser iii in 732 b.c.e. This destruction left Beth Shean as nothing more than uninhabited ruins.

Later History

After the Assyrian deportation of the inhabitants of the northern kingdom of Israel, many of Israel’s great sites were left uninhabited. Though the Samaritans moved into the central highland sites of Samaria, some peripheral lowland sites were left undisturbed. Beth Shean was left desolate and empty for over a century.

First-century c.e. Roman author Pliny the Elder and eighth-century c.e. Byzantine historian George Syncellus both noted that a people called the Scythians, while coming from Media on an excursion to Egypt, “overran Palestine and took possession of Baisan (Beth-Shean), which from them is called Scythopolis” (according to Syncellus). At first, a new city grew on top of the tel. But later into the Hellenistic period, the city gradually relocated to “lower Beth Shean,” which lies in the field southwest of the tel.

Scythopolis is mentioned several times in the Apocrypha. 2 Maccabees 12:29 tells of Judas Maccabeus leading a campaign to take cities such as Carnion, Ephron and Scythopolis during the second century b.c.e.

The first-century b.c.e. Roman general and statesman, Pompey the Great, brought the regions of Judea and Samaria under the rule of the Roman Republic in 63 b.c.e. Rome then made Scythopolis an administrative city for the region. Scythopolis became the most prominent city of a notorious league of ten Hellenized cities, called the Decapolis. The other nine cities in the Decapolis were east of the Jordan River, further from the lands of Judea.

Though neither Beth Shean nor Scythopolis is mentioned by name in the New Testament, the Decapolis is referenced several times. Matthew 4:25 states that “there followed [Jesus] great multitudes of people from Galilee, and from Decapolis, and from Jerusalem, and from Judaea, and from beyond Jordan” (King James Version). The fact that this scripture says “and from beyond Jordan” implies that this Decapolis city mentioned was on the near side of the Jordan, which would mean that it was Scythopolis/Beth Shean. Other references include Mark 5:20 and 7:31.

In the second century c.e., amidst Pax Romana under Hadrian and the Antonines, Beth Shean became one of the great weaving centers of the world—supplying textiles throughout the territories of Rome (this is attested to in Diocletian’s Edict of Maximum Prices, 301 c.e.). Growing cotton was the primary source of income for the surrounding valley and its villages.

In later centuries, the population of Beth Shean came to be increasingly Christian and also saw a resurgence in its Jewish population during the Byzantine period. The city expanded and enveloped the tel and the region to the west. Beth Shean reached its greatest heights in size and population in the sixth century c.e., with an estimated 40,000 people living there.

Upon being conquered by the Muslim Rashidun caliphate under Umar ibn al-Kahttab in 634 c.e., Beth Shean shrank quickly. The Muslims renamed the city Beisan (derivative of Beth-Shean). Though the Muslims did not raze the city, lack of maintenance and a change of economy depopulated the city, and those who remained were poor. In 749 c.e., a colossal earthquake leveled much of what remained in the city. (Beth Shean is located in a region prone to earthquakes, between the African and Arabian plates.)

In the 12th century, crusaders built a hasty fortress in Beth Shean using stones taken from its ruins. After their defeat, Beisan became a small Arab village.

Today, the population of Beth Shean numbers around 20,000. Beth Shean is a center for cotton growing and textile weaving, as in the days of Rome. The city has also become a popular tourist destination, with visitors hoping to catch a glimpse today of the great ancient city that once commanded the surrounding valleys. Visitors can walk the colonnaded Roman cardo and gaze upon the massive tel—recalling Beth Shean’s tremendous and tumultuous history.

Articles in This Series:

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ai

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Azekah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beersheba

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shean

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Beth Shemesh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Dan

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Ekron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gath

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hazor

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Hebron

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jerusalem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Khirbet Qeiyafa

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Lachish

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Megiddo

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Mizpah

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Samaria

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shechem

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Shiloh

Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Sodom

Videos in This Series:

Touring the Bible’s Buried Cities: Gezer