It’s one of the most famous accounts of the biblical Judges period: Gideon and his 300 versus the Midianites. It’s certainly a dramatic story (set many centuries before the equally dramatic story of Sparta’s own “300”).

But what, if anything, can be said for the account historically? Does archaeology have anything to say? It certainly does—in particular, with a fascinating discovery made this year.

In this installment of our “Battles of the Judges” series, we look at Judges 6-8—Gideon v. Midian.

Oppression of the Desert Tribes

“And the children of Israel did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord delivered them into the hand of Midian seven years” (Judges 6:1).

This Judges account picks up during another “sin cycle” for Israel—prosperity, followed by complacency and degeneration into sin, followed by invasion and oppression by a foreign power. This time, it was an oppression of the desert tribes, the Bedouin-like Midianites (primarily), as well as other similar peoples, including the “Amalekites, and the children of the east,” and “Ishmaelites” (verse 3; Judges 8:24; also notable is that the Midianites and Ishmaelites were likewise descendants of Abraham—Genesis 16; 25:1-2).

Judges 6 describes the Israelites planting their crops and the produce being devoured entirely by the marauding desert tribes (fulfilling specific curses for sin, as prophesied in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28). The situation became so severe that the Israelites were forced to live in “dens which are in the mountains, and the caves, and the strongholds” (Judges 6:2) and to harvest their food in secrecy (verse 11). The Midianites ate up Israel’s produce and inhabited the territory “as grasshoppers for multitude; for both they and their camels were without number: and they entered into the land to destroy it. And Israel was greatly impoverished because of the Midianites; and the children of Israel cried unto the Lord” (verses 5-6; King James Version).

It’s difficult to pinpoint exact dates for this oppression, but internal chronology indicates sometime during the 12th century b.c.e. It’s notable that the field of archaeology, including the study of pollen remains from Israel and texts from Egypt and Turkey, reveals a lengthy famine during this 12th-century period (also see Ruth 1:1). This could explain the Midianite piracy into Israel for food, the Israelites’ desperate attempts to grow produce for themselves, a tendency to withhold food even from fellow Israelites (Judges 8:6), and even a dream about bread (Judges 7:13).

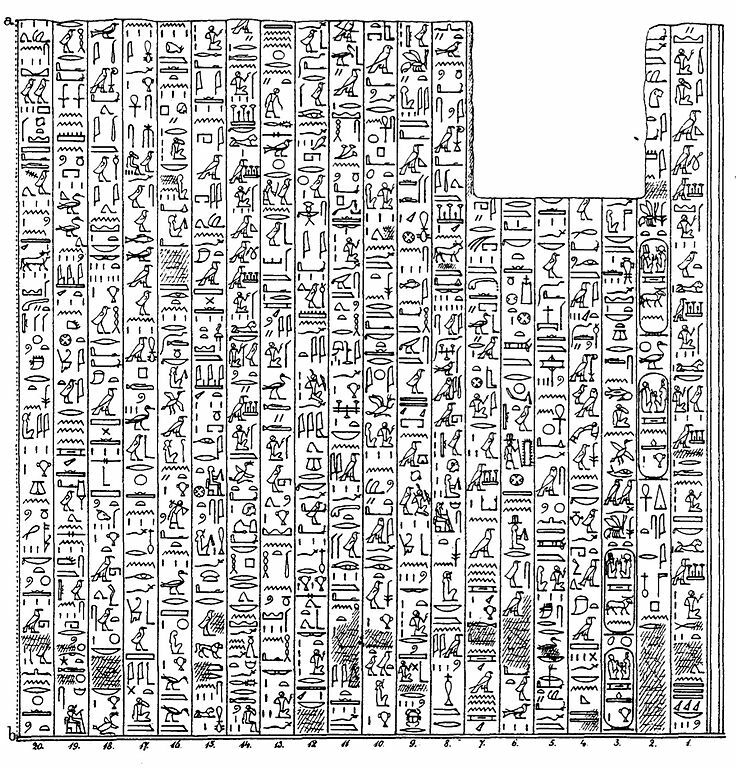

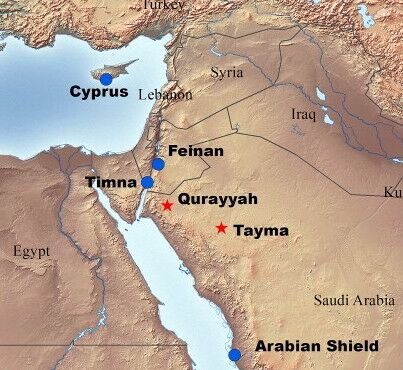

Perhaps unsurprisingly, due to their Bedouin-like biblical description, the exact historical identity of the Midianites remains unknown. Some researchers posit that they constituted some sort of nomadic northern Arabian confederation, of which there were plenty such tribes during this period. There is a notable body of pottery known as “Midianite Pottery,” also called “Qurayyah Painted Ware” (with Qurayyah, in northwest Saudi Arabia, identified as the central place of origin—a location that would fit within the general geographic bounds of biblical Midian). This definitive pottery style, containing motifs of humans and animals, dates specifically to the 13th-12th centuries b.c.e.—fitting with this period of Midianite dominance in question—and has been found in locations extending as far north as central Israel and central Jordan. Of course, this could be simply the result of trade—but a spread of “Midianite” ware, specifically around the 12th century b.c.e. into Israel and central Jordan, fits with a Midianite incursion into the land attributed to this period. More on this further down.

Introducing ‘The Hewer’

As a result of Israel’s crying out to God, a man was chosen to lead the nation out of captivity. “And the angel of the Lord came, and sat under the terebinth [tree] which was in Ophrah, that belonged unto Joash the Abiezrite; and his son Gideon was beating out wheat in the winepress, to hide it from the Midianites. And the angel of the Lord appeared unto him, and said unto him: ‘The Lord is with thee, thou mighty man of valour.’ … ‘Go in this thy might, and save Israel from the hand of Midian …” (Judges 6:11-12, 14). The name Gideon means “hewer,” or “stone-cutter.” But here we will focus on this west-Manassite’s alternate name.

Following his call from God, Gideon promptly destroyed his father’s idols and altar to Baal, replacing it with an altar dedicated to God. The regional outcry over this deed indicates that his father was a prominent man in the tribe of Manasseh. “Then the men of the city said unto Joash: ‘Bring out thy son, that he may die; because he hath broken down the altar of Baal …’” (verse 30). What next transpired gave Gideon his new name, which has a fascinating archaeological link.

“And Joash said unto all that stood against him: ‘Will ye contend for Baal? … if he be a god, let him contend for himself, because one hath broken down his altar.’ Therefore on that day he was called Jerubbaal [‘Baal will contend’] …” (verses 31-32).

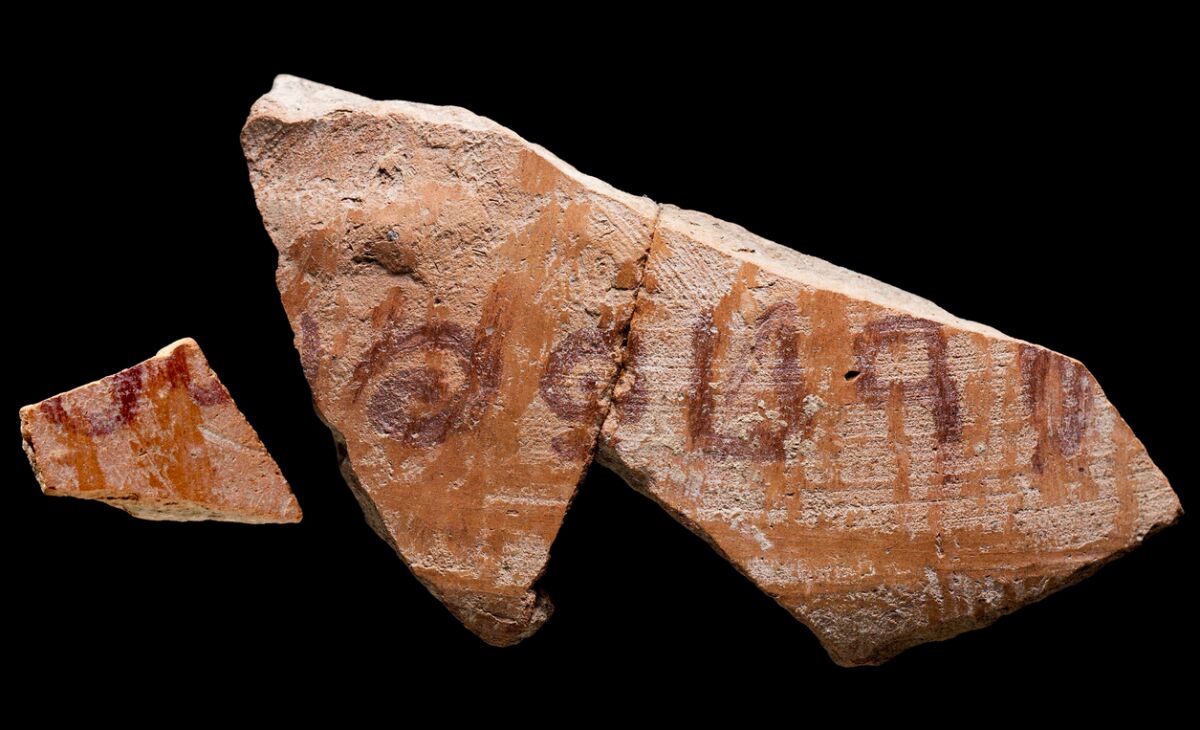

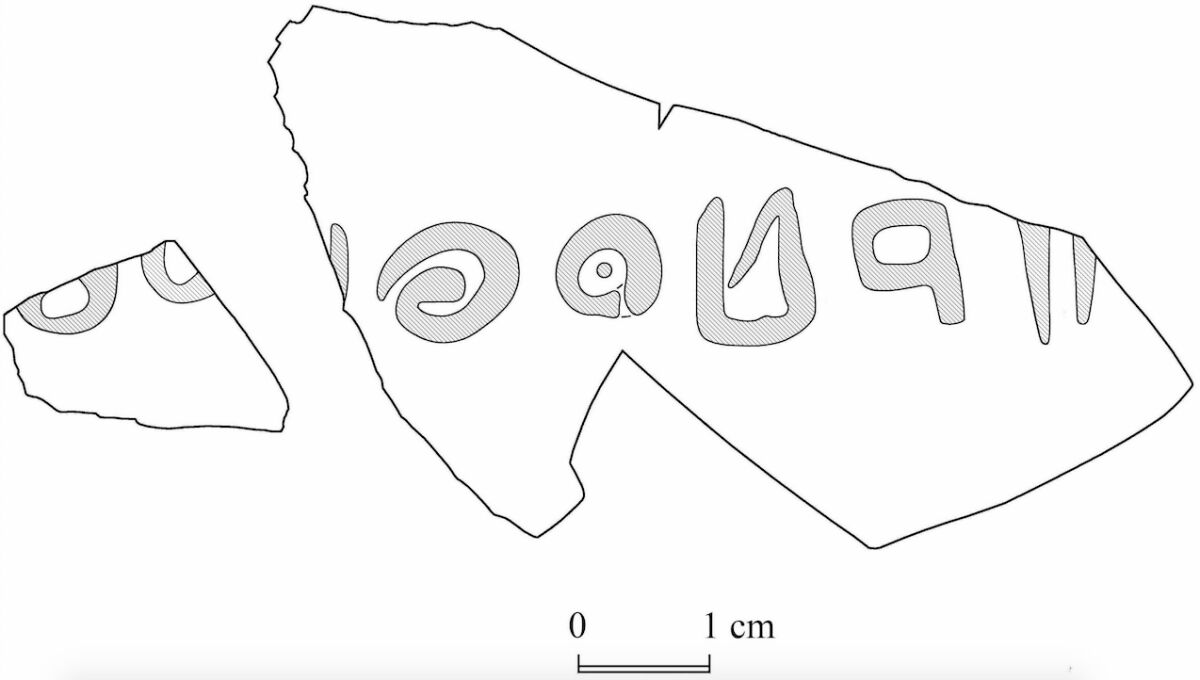

Earlier this summer, Prof. Yossi Garfinkel released the discovery of an ostracon that his team discovered at the site of Khirbet al-Ra’i. The inked pottery sherd, dating to around 1100 b.c.e., bore the name Jerubbaal. This constitutes the first-discovered contemporary inscription bearing the name of a biblical judge. Of course, it is still up for debate as to whether or not this was the Jerubbaal of the biblical account. Some have noted the roughly 120-kilometer distance between this findspot and the famous battle between Gideon/Jerubbaal and Midian.

However, several points indicate the likelihood that this is the Jerubbaal of the Bible:

- The ostracon dates to the same time period (end of the 12th century b.c.e.)

- Jerubbaal’s fame spread across all Israel (and even led to a brief, ill-fated kingship and pilgrimages from “all Israel” to his hometown)

- Jerubbaal’s large family included 70 sons, who themselves would have necessarily spread over a vast area

- The findspot of Khirbet al-Ra’i can be linked to the Gideon account—Judges 6:4 shows that the Midianite oppression extended all the way to include this general territory on the Philistine border

- The name Jerubbaal is a rare one, mentioned only in the Bible in connection to Gideon and found only on this potsherd dating to the same period.

- The meaning of the name, as explained in Judges 6, makes it one that would not necessarily be favorable to either a follower of God or Baal—thus explaining a rarity of use.

So the evidence is tantalizing that this is the Gideon/Jerubbaal of the Bible—but at the very minimum, the ostracon gives precedence to the use of the name during this period. (And as for Baal—his worship is well attested throughout the Levant at this point.)

300

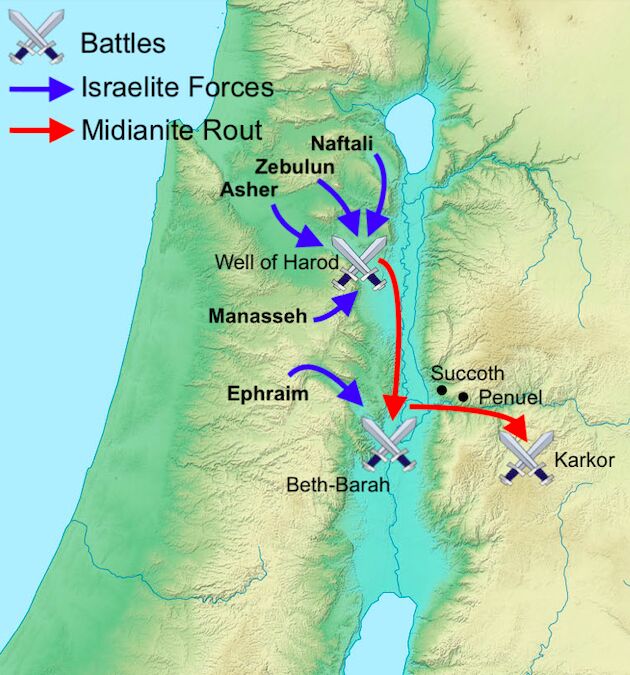

The Bible relates that Jerubbaal initially drew a strong following of 32,000 men, encamped at the Well of Harod (Judges 7:2-3, kjv). However, in order that victory would be attributed to God rather than the men, that number needed to be whittled down. All those harboring any fear of the upcoming conflict were sent home “from mount Gilead”—22,000. A final test of readiness for battle at the spring waters (based on the way the men drank from the waters) saw the number of chosen men drop to 300—less than 1 percent of the original force.

The location of the Well of Harod has been identified since at least 1856 with the site Ain Jalut, which has a large cave (“Gideon’s Cave”) from which spring water emerges. The Arabic name Ain Jalut means “Spring of Goliath” (believed to be a late mistaken geographic association). Jalut has also been explained as a possible corruption of the name Gilead, which features in the same context as the Well of Harod (verse 3). This is important, because the mountains of Gilead are nowhere near this biblical location. However, on one of the mountaintops near the Ain Jalut spring is a rock formation known as a “gilead,” measuring 8 x 10 meters in size, which existed during this period. This may be identified as the Gilead mentioned in verse 3 (rather than the actual mountains of Gilead located to the east of the Jordan River. For more information, note the following article by Gidi Yahalom).

It’s interesting to note that this force of 300 preceded the famous 300 of Sparta by nearly 700 years—and perhaps already had symbolic significance in Israel due to Abraham’s victory against the armies of Mesopotamia with just 318 men (Genesis 14). There are several other Greek references to the use of 300 warriors. It’s no secret that many Greek stories parallel the biblical, and may be the result of close links or trade between the two, as mentioned in the Bible. Furthermore, the Spartans considered themselves directly related to the Israelites! (For more information, read my article: “The Spartans: ‘Children of Abraham, Brothers of the Jews’.”)

As an aside, this location of Ain Jalut—which witnessed this turning point in Israelite history—was also the location of another significant turning point nearly 2,500 years later: the Battle of Ain Jalut in c.e. 1260, where the rapidly expanding Mongol Empire was for the first time permanently beaten back.

Trumpets, Camels and Havoc

In the darkness of midnight, Gideon and his 300 approached the large encampment of Midianites, Amalekites and Ishmaelites. The tools they were carrying—trumpets, clay vessels and flaming torches (Judges 7:16)—seem peculiar at first; yet in the darkness of night, it was the perfect weapon for creating absolute chaos. Verses 19-22:

So Gideon, and the hundred men that were with him [the 300 were divided into three companies], came unto the outermost part of the camp in the beginning of the middle watch …. And the three companies blew the horns, and broke the pitchers, and held the torches in their left hands, and the horns in their right hands wherewith to blow; and they cried: “The sword for the Lord and for Gideon!” And they stood every man in his place round about the camp; and all the host ran; and they shouted, and fled. And they blew the three hundred horns, and the Lord set every man’s sword against his fellow, even throughout all the host; and the host fled ….

The terror of this event, for the enemy—300 piercing horns sounding in the middle of the night, along with the smashing of hundreds of pots and the sudden blinding light of 300 flaming torches—would be hard to describe (especially since they were already in a fearful state; verses 13-14). After all, Numbers 31 describes a devastating battle against the Midianites centuries earlier, in which one Israelite sounded the trumpet for war—but 300 trumpets at midnight? It must have seemed a gargantuan fighting force.

It’s worth noting that these enemy desert tribes possessed “camels … without number” (Judges 7:12). Certainly these creatures would have been terrifically spooked, causing utter mayhem themselves. A poignant recent example is a circus incident in Pittsburgh in 2018, in which one of the camels was spooked by a trainer dropping a tool on the ground next to it; the hefty beast charged toward the audience and injured seven people, including six children.

It’s also of note that some effort has been made among certain scholars to portray the presence of camels in the Levant as anachronistic—that archaeology shows camels did not become domesticated in this region until the 10th century b.c.e., thus relegating all earlier mentions (such as this account of camels in the book of Judges) to fable. However, the archaeological record affirms the very opposite. For more information, read our article “Camels: Proof That the Bible Is False?”

As the Bible relates, Gideon’s successful rout initially resulted in the capture and slaughter of the Midianite princes Oreb and Zeeb at two notable sites near the Jordan River—the Rock of Oreb and the Winepress of Zeeb (verse 25). The names Oreb and Zeeb mean “raven” and “wolf,” respectively. Interestingly (as related by the Cambridge Bible commentary), there are two conical hills located near Jericho, not far from the Jordan River, whose old Arabic names translate to “raven’s nest” and “ridge of the wolf”—pointing to a possible tradition carried on following these events described in the Book of Judges.

Retribution Against the Israelites

As Gideon’s now-weary 300 routed the Midianites into Jordan, they passed by two trans-Jordan Israelite cities—Succoth and Penuel. Both cities refused to believe that Gideon’s men had the Midianites on the run—and both refused to provide food for the weary soldiers (again, perhaps also in the context of a wider period of famine). As such, Gideon promised that on their victorious return through the area retribution would be in order. Following this, the Midianite kings Zebah and Zalmunna were successfully captured, the Midianite forces were totally destroyed, the spoils of war were retrieved, and Gideon’s men returned the way they had come—to mete out justice.

The identification of Penuel is still uncertain, but may be linked to the modern Jordanian site Tulul adh-Dhahab. Succoth is identified as the modern Jordanian archaeological site Deir ‘Alla, just beyond the Jordan River and just west of Tulul adh-Dhahab. (A primary clue for Succoth as Deir ‘Alla is a reference in the Jerusalem Talmud, dating to the third century c.e., which names Succoth as “Darʿala.”)

Excavations at Deir ‘Alla have revealed a significant occupation during this Late Bronze Age period, including some degree of destruction to the city’s storerooms during the 12th century b.c.e. The Bible briefly describes Gideon’s retribution of Succoth (he “took the elders of the city, and thorns of the wilderness and briers, and with them he taught the men of Succoth”—Judges 8:16). However, his actions against Penuel demonstrate a more violent conflagration (“he broke down the tower of Penuel, and slew the men of the city”—verse 17). Perhaps Succoth too witnessed some further level of physical destruction. In any event, it is interesting that the storerooms of Deir ‘Alla were burned during the 12th century—after all, it was the city’s “stores” that had been denied Gideon and his men.

Innocence of Youth, and Earrings

The conclusion to the story of Gideon mentions several interesting elements. Judges 8:18-19 indicate that Zebah and Zalmunna had presided over the deaths of Gideon’s family members during an earlier battle—and once this became known to Gideon, he condemned the two kings to death, giving the “honor” of slaying them to his son Jether. “But the youth drew not his sword; for he feared, because he was yet a youth. Then Zebah and Almunna said: ‘Rise thou, and fall upon us; for as the man is, so is his strength.’ And Gideon arose, and slew Zebah and Zalmunna …” (verses 20-21).

Then we come to an interesting observation regarding the Ishmaelites. In gratitude to Gideon, the Israelites bequeathed him with the immense quantity of earrings that had been gathered from the bodies—1,700 shekels worth of gold—“[f]or they had golden ear-rings, because they were Ishmaelites” (verse 24). Evidently earrings were all the rage amongst this tribe.

The first-century c.e. historian Pliny the Elder (who, as an aside, was killed while attempting a daring rescue mission during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius) made the following brief observation in his work Historia Naturalis (in the chapter describing “The Ears”): “There is no part of the body that creates a more enormous expense for our women, in the pearls which are suspended from them. In the East, too, it is thought highly becoming for the men, even, to wear gold rings in their ears” (xi.50).

Such was the case with these eastern nomads—and such was the enormous amount of gold, that the memorial that Gideon cast out of it for his hometown became an object of pilgrimage and pagan worship. “[A]nd all Israel went astray after it there; and it became a snare unto Gideon, and to his house” (verse 27). And with his newfound fame, Gideon swiftly acquired “many wives,” from which were born 70 sons (verse 30). The stage was being set for another round of calamity for Israel.

Still, “the land had rest forty years in the days of Gideon” (verse 28).

Tumbling Bread, Rocks and the Fall of Midian

As mentioned at the top of this article, the “Qurayyaites” may be our Midianites of this judges period—thriving for only a short period, only to completely disappear at the end of the 12th century b.c.e. Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen summarizes the Midianites in his famous book On the Reliability of the Old Testament (emphasis added):

After that date the Egyptians left [Timna, a region in southern Israel just north of the Gulf of Aqaba, circa 1150 b.c.e.], and for a short time the Midianites/Qurayyaites stayed around and built their own tent shrine, leaving when a rockfall crushed it. By around 1100 or so they were gone. And soon afterward their main “capital” at Qurayya and its irrigation agriculture also passed into oblivion. The probable Midianites and their settled culture simply disappeared.

This reference to a notable “rockfall” that crushed an important Midianite/Qurayyaite tent shrine in southern Israel at the end of the 12th century is a fascinating tidbit. Note Judges 7:9-11, where God encourages Gideon and his aide to eavesdrop on the encamped Midianites at night before attacking, to hear the sentiments being expressed. They hear the following dream being related by one of the Midianites through the tent wall (verses 13-14):

“Behold, I dreamed a dream, and, lo, a cake of barley bread tumbled into the camp of Midian, and came unto the tent, and smote it that it fell, and turned it upside down, that the tent lay flat.” And his fellow answered and said: “This is nothing else save the sword of Gideon the son of Joash, a man of Israel: into his hand God hath delivered Midian, and all the host.”

During this same period, a rockfall did crush an important Qurayyaite tabernacle shrine. Perhaps if this event had already occurred, it may have been seen by the troops as an omen—or perhaps a preemptive vision of their final destruction. Whatever the case, by the end of the 12th century b.c.e., the Qurayyaite culture was gone—as the Judges account relates.

Kitchen concludes with the following observation: “The interest of this set of facts is that, if the Exodus-Numbers-Deuteronomy and Judges narratives had only been first invented many centuries later (e.g. in the sixth to third centuries [as is popularly posited by revisionist scholars]), nobody would ever have heard of Midianites to be able to write stories about them. … Thus the narrations about Midian ought to have their origin in conditions that obtained in the 13th and 12th centuries”—as a recounting of authentic events.

The Body of Evidence

Each installment of this series is often concluded by stating that “archaeology has not yet ‘proved’ the existence of” the specific judge in question. But in the case of Gideon, it may well have. Certainly, the wider biblical account fits remarkably well with the evidence from the historical period:

- Famine conditions in Israel and beyond, leading to region-wide upheaval, concluding at the end of the 12th century b.c.e.

- The rise of a Qurayyaite/Midianite culture in the 13th-12th centuries b.c.e., traceable all the way into Israel and central Jordan

- The utter demise and disappearance of this culture around the end of the 12th century b.c.e.

- The destruction of a Qurayyaite/Midianite shrine by falling objects during the 12th century b.c.e.

- The occupation of Deir ‘Alla/Succoth during the 12th century b.c.e., and the destruction of storehouses during this time period

- Evidence of an apparently prominent individual named Jerubbaal on the scene at the end of the 12th century b.c.e.

- The presence of a stone “gilead” near the site of “Gideon’s Cave” during the 12th century b.c.e.

- Arabic-named sites matching key points in the story of Gideon

- And a continuing tradition, in following centuries, of celebrating forces made up of 300 warriors.

As a result of Gideon’s efforts, the nation of Israel rallied around him with the desire to make him king. “And Gideon said unto them: ‘I will not rule over you, neither shall my son rule over you; the Lord shall rule over you’” (Judges 8:23).

Trouble was, one of Gideon’s sons did try to rule over Israel. And as we will cover in the next installment, utter calamity ensued.

Articles in This Series:

Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Shamgar v. the Philistines: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Sisera v. Deborah: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Gideon v. Midian: Evidence for the Biblical Account