You’d be forgiven for not being familiar with the account of Shamgar “saving Israel” in the book of Judges. After all, it is contained in only one verse—in the original Hebrew language, only 18 words long.

“And after him was Shamgar the son of Anath, who smote of the Philistines six hundred men with an oxgoad; and he also saved Israel” (Judges 3:31).

What, if anything, can be said for such a short account—let alone historically? As it turns out, quite a lot.

Before Samson and the Philistines, there was Shamgar and the Philistines: In this fourth article in our “Battles of the Judges” series, we’ll examine his story.

A Sad State of the Union

First, let’s establish the biblical chronology for this account. Shamgar is described immediately following the accounts of the first two judges of Israel, Othniel and Ehud. Verse 31 shows that he was on the scene during, or just after, Ehud—during or just after an 80-year period of peace for Israel from the Moabites in the east (verse 30). Crunching the numbers found in earlier verses, this probably puts us somewhere in the late 13th century b.c.e., roughly 150 to 200 years after the Israelites’ entry into Canaan (around 1406 b.c.e.; verses 30, 14, 11, 8).

We can get a good sense of the state of Israel during the time of Shamgar—because though his story is contained in only one verse, he is also referenced in passing in the “Song of Deborah,” in Judges 5. This song relates the tragic state of Israel in the early Judges era: “In the days of Shamgar the son of Anath, in the days of Jael, the highways ceased, and the travellers walked through byways. The rulers ceased in Israel, they ceased …. They chose new gods; then was war in the gates; was there a shield or spear seen among forty thousand in Israel?” (Judges 5:6-8).

The chapter continues to describe the poor, absolutely fragmentary state of the different tribes of Israel—little-to-no unification. And this picture fits startlingly well with the archaeological record.

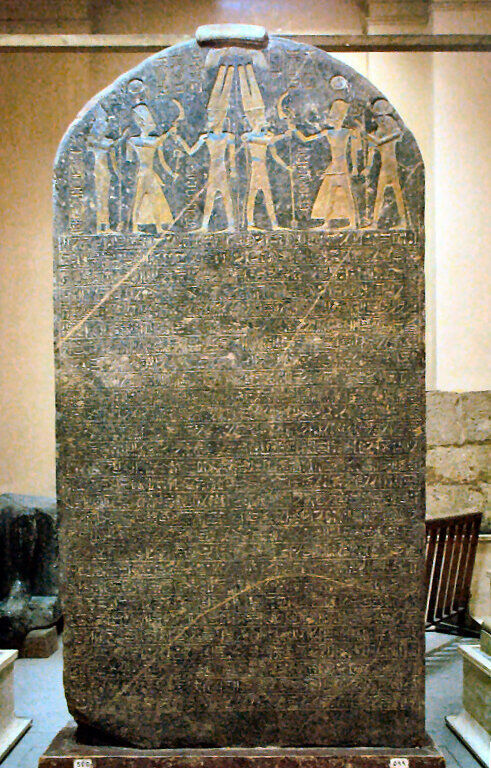

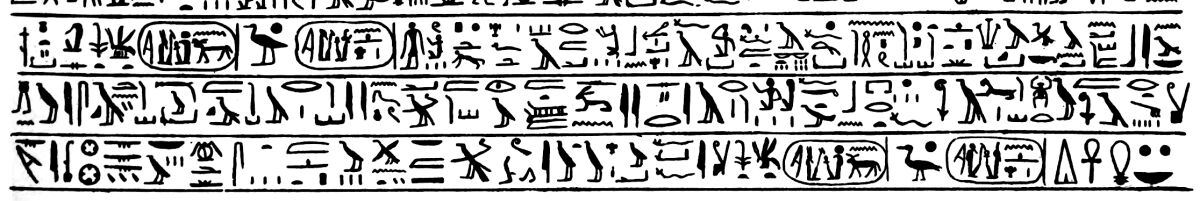

One of the chief singular items of evidence for this is the Merneptah Stele. Dating to this century (around 1209 b.c.e.), it is recognized as the earliest “confirmed” mention of the name Israel. And the record on the stele is a virtually identical match to the “Song of Deborah”:

Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe,

Ashkelon has been overcome

Gezer has been captured

Yanoam is made nonexistent

Israel is laid waste, and his seed is not ….

This 13th-century b.c.e. picture, then, of a lowly and oppressed Israel fits well with the world in which Shamgar arose.

And so does the archaeological evidence of the rise of his enemies.

Entry of the Philistines

The Philistines are well known for being the adversaries of Israel—particularly highlighted throughout the accounts of Samson and, later, David. And there is a special archaeological link to this rise in strife with the Philistines.

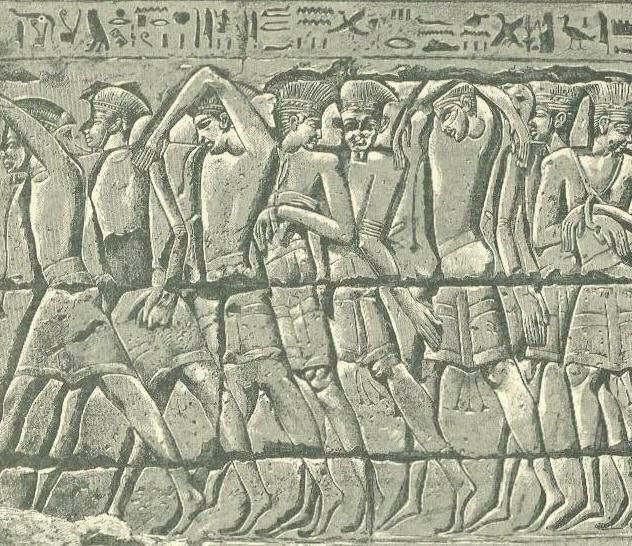

The earliest archaeological records of the Philistines are found in Egyptian inscriptions. These records list the Peleset peoples as having come from the sea (part of the enigmatic “Sea Peoples”), and attacking the Egyptian mainland around 1200 b.c.e. Apparently they were attempting to expand land settlement along the southern Mediterranean coast; however, the Egyptians successfully beat them back, limiting their presence to the Levant coast, alongside Israel.

Just two years ago, dna analysis on Philistine graves at Ashkelon established that a main body of Philistines arrived in the land in a large migratory wave from Crete, sometime around the mid-13th century b.c.e. Shamgar’s early encounter with this warlike people fits with their early migration, with a build-up of trouble that would eventually hit critical mass in the 12th to 11th centuries as the Philistines became settled—at the time of Samson, Saul and David.

Synonymous with this early Philistine arrival: Last year, archaeologists discovered a small “Canaanite fort” dating somewhere around 1200 b.c.e., right on the border of Philistine territory. According to the excavators, this limited structure appears to have been built to deal with the “new geopolitical situation”—particularly the arrival of the Philistines. This small fort–watchtower fits nicely alongside the “small” account of Shamgar’s early Philistine resistance, before the Philistines became especially bloated in the land as a powerful fighting force.

As for the number of Philistines Shamgar faced, 600, this was actually a common military unit. The early Spartans and Greeks divided their troops up into Morae, groups of 600 men (depending on the historical source). Another early Greek unit, the Lochos, likewise often had about 600 men. So a reference to a parallel-sized unit among a related Mediterranean people, the Philistines, fits well.

Who Was Shamgar?

So now to the question at hand: Who was Shamgar? This is where things get especially interesting: By all accounts, he appears to have been a foreigner used by God to help free Israel.

The name Shamgar is not used for any other individual in the Bible. It is of completely unknown origin or derivation. Further, the associated name Anath is also only used in this reference as a proper name in the Bible. (By way of comparison, the name Elijah is famous for the prophet—but four different biblical individuals share this name.) Here, we have no direct biblical parallels for either personal name.

Furthermore, there are half a dozen other short-verse “judges”—yet pains are taken for every single one to describe their tribal identity, as well as stating that they “judged Israel.” Here, no tribal identity is given to Shamgar, neither is he described as “judging Israel.”

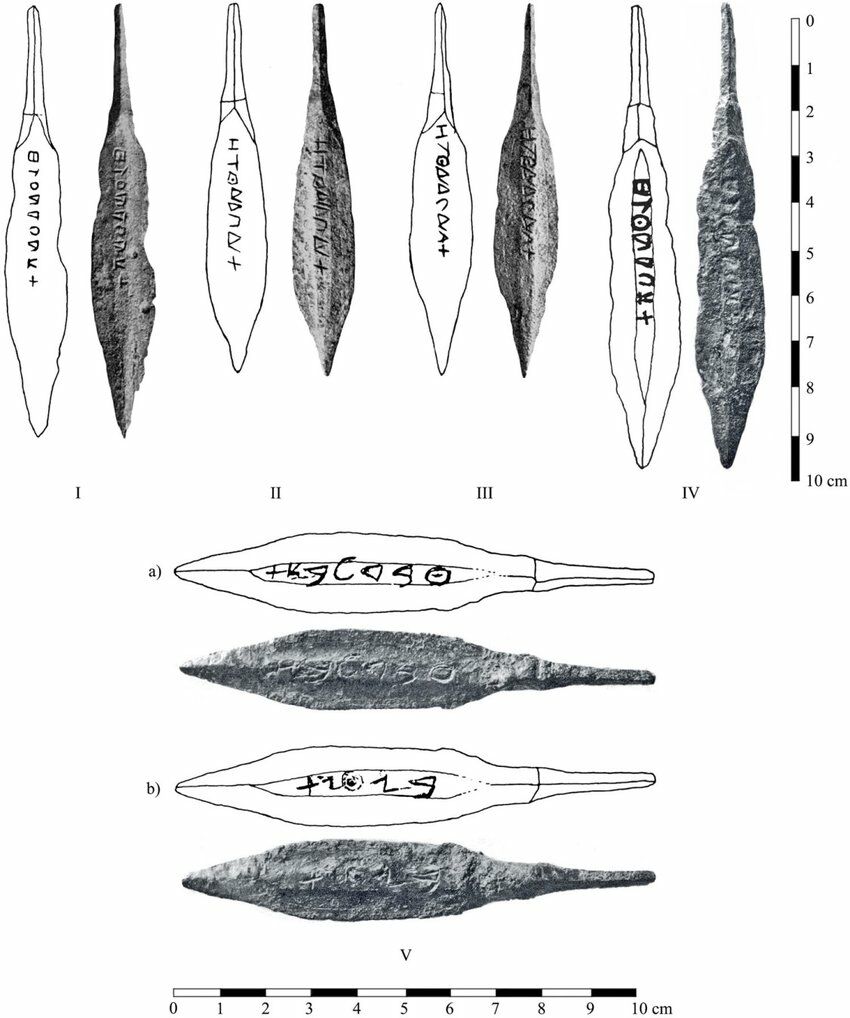

The name Anath is unusual in that it is a feminine word. This is peculiar because names throughout the Bible usually follow the pattern [name], son of [father’s name]. But Anath is the name of a well-known goddess found throughout the Levant during this period and beyond. And remarkably, the term ben Anath (“son of Anath”) has been revealed by archaeology as a known warrior title from the judges-era Levant!

During the 1950s, a hoard of arrowheads were discovered in the region of Bethlehem (itself not too far from then-Philistine territory). These arrowheads, dating to around 1100 b.c.e., each carried an inscription mentioning a personal name and “son of” a deity. One arrow read the following:

Abed-Labeth, son of Anath

Such finely-crafted arrowheads evidently belonged to a select band of warrior men (again fitting, because Anath was a war-goddess). They thus provide early evidence for the use of this title during the “judges era,” fitting with a Shamgar ben Anath.

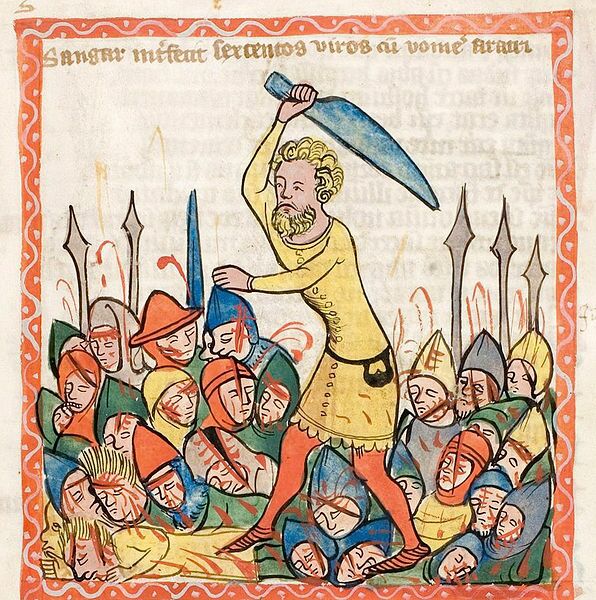

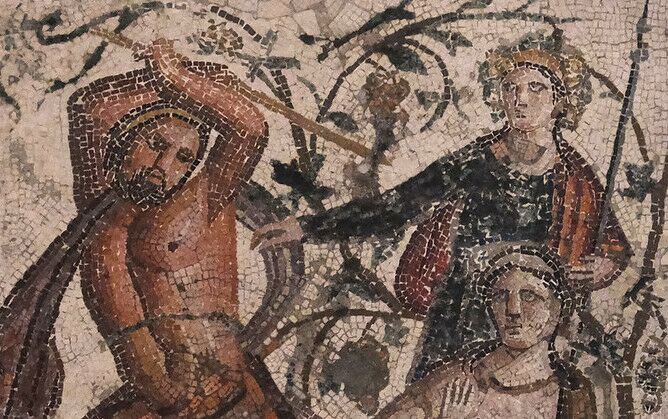

As for the name Shamgar, there is a historical association with this as a foreign name from further afield. The ancient Septuagint records his name as Samigar. Sangar was the name of a king of the northern Mesopotamian city of Carchemish, who reigned from circa 900-850 b.c.e., as recorded in Assyrian and Luwian inscriptions. (Note also the above early medieval depiction of Shamgar, which curiously names him precisely the same—Sangar.) A closely matching foreign name Samgar can also be found in Jeremiah 39:3: “All the officials of the king of Babylon entered and sat at the Middle Gate: Nergal-sharezer, Samgar, Nebusarsechim … and all the rest of the officials of Babylon’s king” (csb).

The name Shamgar, then, appears to have historical north Mesopotamian precedent. This was identified early on by our “old friend” and excavation director Prof. Benjamin Mazar, who in 1934 wrote that the name was not Semitic but most likely Hurrian (Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 66:4, 192-194). His nephew, Prof. Amihai Mazar, continued in the same vein, writing that the collapse of the far northern Syrian kingdom of Yamhad (circa 16th century b.c.e.) led to an “influx of Hurrian population from northern Mesopotamia into Syria; a thinner stream of these people advanced farther to the south and appeared in Palestine. Thus some change in the ethnic composition of Canaan occurred [thus corresponding to Shamgar] and was to become an important factor in the following period” (Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 b.c.e.).

The historical account, then, fits well with the biblical. And several other ancillary points come together to help identify Shamgar as a non-Israelite. He is described by Deborah alongside Jael, a member of the foreign Kenite tribe (Judges 4:17). “In the days of Shamgar the son of Anath, in the days of Jael … The rulers ceased in Israel, they ceased, until that thou didst arise, Deborah, … a mother [margin, leader] in Israel” (Judges 5:6-7). In this specific period of weakness and poverty, in the days of Shamgar and Jael, Israelite leadership was not to be found.

Likewise, the mention of “and he also saved Israel” at the end of Judges 3:31 could also indicate a separation between this man God used and the nation that benefited from his actions.

And could he, in his limited resistance, perhaps have had something to do with the construction of the small “Canaanite,” anti-Philistine fort at Galon?

Death by Oxgoad

What about the weapon? The item used by Shamgar highlights the poverty in the land at the time—as Deborah later said, “not a spear among forty thousand.” The tool used by Shamgar is translated as an oxgoad. This word is another special case: It is used only once in the entire Bible. Two Hebrew words are used to describe it: malmad baqar, or literally, “cattle-teacher”—hence, oxgoad or cattle prod—an item that continues to be used in farming communities to this day.

An oxgoad is simply a sharpened rod used to drive cattle forward during plowing or other activities. They can be quite imposing spear-like weapons, with some examples reaching up to 2.5 meters (8 feet) long with a shaft up to 15 centimeters (6 inches) in circumference. The front end is typically sharpened (or tipped with a metal point), and there is often a metal hook at the rear end for cleaning clods from the plow. Shamgar could have used this device as a two-ended stabbing, clubbing and slicing device.

The sheer gore of mass-killing by the use of essentially a wooden stake is difficult to imagine. But here again, due to Israel’s rebellion, this was the path the nation had chosen (as opposed to trusting God to drive their enemies out—Exodus 23:27-28; 34:11). God thus used the foreigners in Israel’s midst to “teach them war” (Judges 3:2—this is perhaps another link to a non-Israelite Shamgar).

The symbolism carries through even to the device itself—an ox-teacher. Israel itself is referred to in the Bible with cattle symbolism: “For Israel is as obstinate as a stubborn cow. Can the Lord now shepherd them like a lamb in an open meadow?” (Hosea 4:16; csb).

And this metaphor of stubbornness and correction happens to be the central theme of the book of Judges.

Later Evidence of the Event?

A later eighth-century b.c.e. Greek myth bears some striking similarity to the account of Shamgar and could serve as evidence for a core historicity of the account. The story tells of an event in the distant past in which the northern leader of Thrace, Lycurgus, used an oxgoad to strike down an army of Bacchus in defense of holy territory. Depending on the source, this oxgoad battle took place in the Holy Land, near Mount Carmel, “a mountain in Judea, which makes it probable that this is hammered out of the [same] sacred history” (Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible).

A great many biblical events and personalities bear resemblance to later mythological stories in the Greek world—perhaps most notably thanks to the well-established trade in the region and Greek-Israelite connection (see here, here and here for more detail). Could this be another example, attesting to an original historic event?

Finally: Though the existence of Shamgar himself has not yet been “proven” by archaeology, could the Merneptah Stele described at the start of this article perhaps be describing Shamgar’s historical actions? Alongside a “wasted” Israel, the stele states, “Ashkelon has been overcome.” Ashkelon was a chief Philistine city to which migrations began earlier in that century. No mention is made of other Philistine cities—only this one. And its defeat came at the same time that “Israel is laid waste”—as Deborah put it, as in the days of Shamgar.

Who, then, in the early 1200s b.c.e. “overcame” these Ashkelonites? Was it the very person we have record of “overcoming” these early Philistines—Shamgar, son of Anath?

The Body of Evidence

Archaeology has not yet “proved” the existence of Shamgar. But the wider biblical account fits remarkably well with the evidence from the historical period:

- Evidence for the utterly fragmented, humiliated state of Israel

- Evidence for a newly arrived, threatening Philistine power in the region

- An accurate size-description of an early Mediterranean military unit

- The presence of limited, non-Israelite military measures being taken against the Philistine threat

- The early use of Shamgar-type names in a foreign context

- Evidence for the judges-era use of the warrior title son of Anath

- A parallel account for the early use of an oxgoad as a desperate defensive weapon to protect a holy land

- Evidence of the “overcoming” of a singular body of Philistines, at a time of Israelite poverty

The period of the Israelite kings, from around 1000 to 586 b.c.e., is well attested to in archaeology. We also now have quite a thorough emerging body of evidence for the Israelite judges: a bloody period in Israel’s earliest history intended to highlight the pitfalls of relativism and following one’s own moral compass. As the book concludes and summarizes in Judges 21:25: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”

So by the end of Judges 3, while Ehud’s victory against Moab led to peace in eastern Israel, Shamgar’s victory against the Philistines led to peace in the west, temporarily “saving Israel.”

“And the children of Israel again did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord, when Ehud was dead. And the Lord gave them over into the hand of Jabin king of Canaan …” (Judges 4:1-2).

Cycle: Repeat.

Articles in This Series:

Othniel v. Chushan-Rishathaim: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Ehud v. Eglon: Evidence for the Biblical Account

Shamgar v. the Philistines: Evidence for the Biblical Account