The famine of the book of Ruth is a pivotal event of the judges period, one that is integral to the ancestry of King David. And research directed by archaeologist Prof. Israel Finkelstein has revealed evidence of this event, from the tiniest of artifacts: pollen samples.

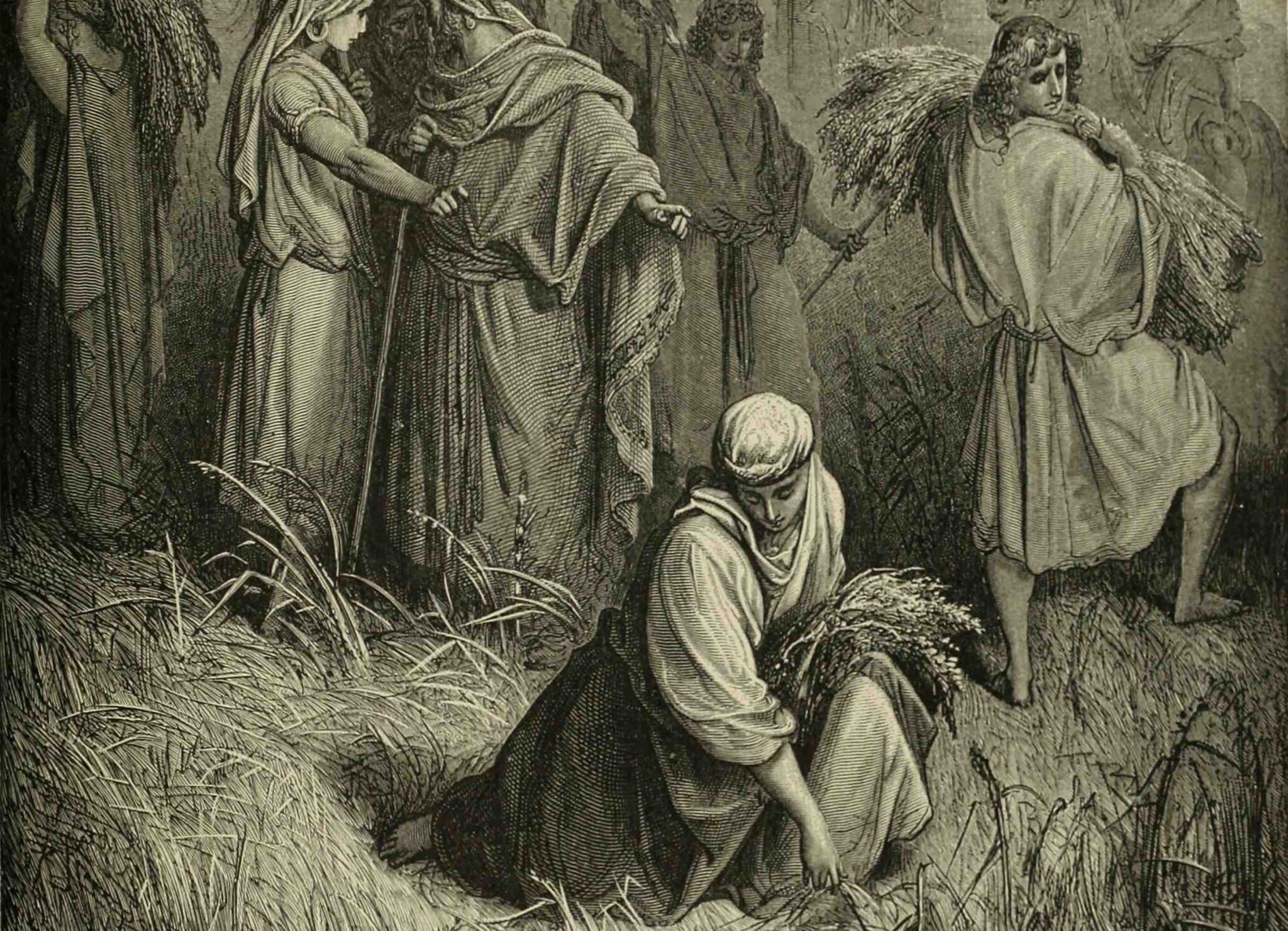

Ruth 1:1-2 in the King James Version read:

Now it came to pass in the days when the judges ruled, that there was a famine in the land. And a certain man of Bethlehem-judah went to sojourn in the country of Moab, he, and his wife, and his two sons. And the name of the man was Elimelech, and the name of his wife Naomi ….

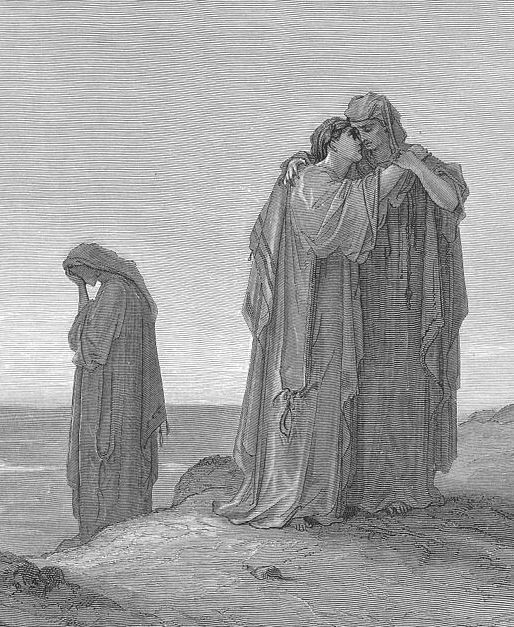

As a result of the famine, Elimelech’s family migrated east into the land of Moab, where his sons married two women—Orpah and Ruth. During their sojourn, Elimelech and his two sons died (verse 5). Finally, after 10 years, Naomi made her return to her homeland with Ruth, after “she had heard in the field of Moab how that the Lord had remembered His people in giving them bread” (verse 6).

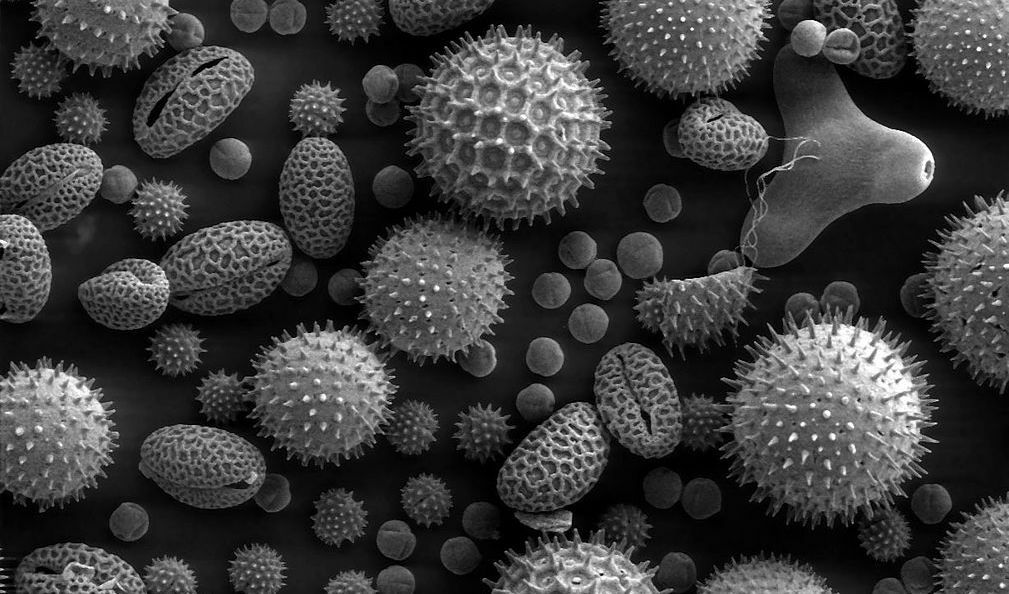

In 2013, scientists from Tel Aviv University (tau) and Germany’s University of Bonn revealed their research of pollen grain samples that pointed to a major, lengthy famine in the Levant, between the years 1250 and 1100 b.c.e.

The Proof Is in the Pollen

Pollen grains are remarkably durable, extremely distinct (each individual plant has a unique “fingerprint” pollen form), and preserve well over millennia in lake or desert environments. The research team drilled sediment cores from the Sea of Galilee and the Wadi Zeelim, near the Dead Sea. Over the course of three years, researchers combed meticulously through the layers.

They discovered that within the period of 1250–1100 b.c.e., there was a sudden, dramatic decrease of Mediterranean trees that require large amounts of water—particularly pines, oaks and carobs. In their place was a rise in the farming of dry-climate trees, such as olives. The researchers identified this as the result of repeat, successive droughts within this 150-year period.

This discovery matches up with other regional pollen samples dating to this period, taken from Egypt, Syria, Cyprus and Turkey. (The Israeli research was unique, however, in its meticulous “chronology control”—parsing the sediment cores into extremely narrow, 40-year intervals.)

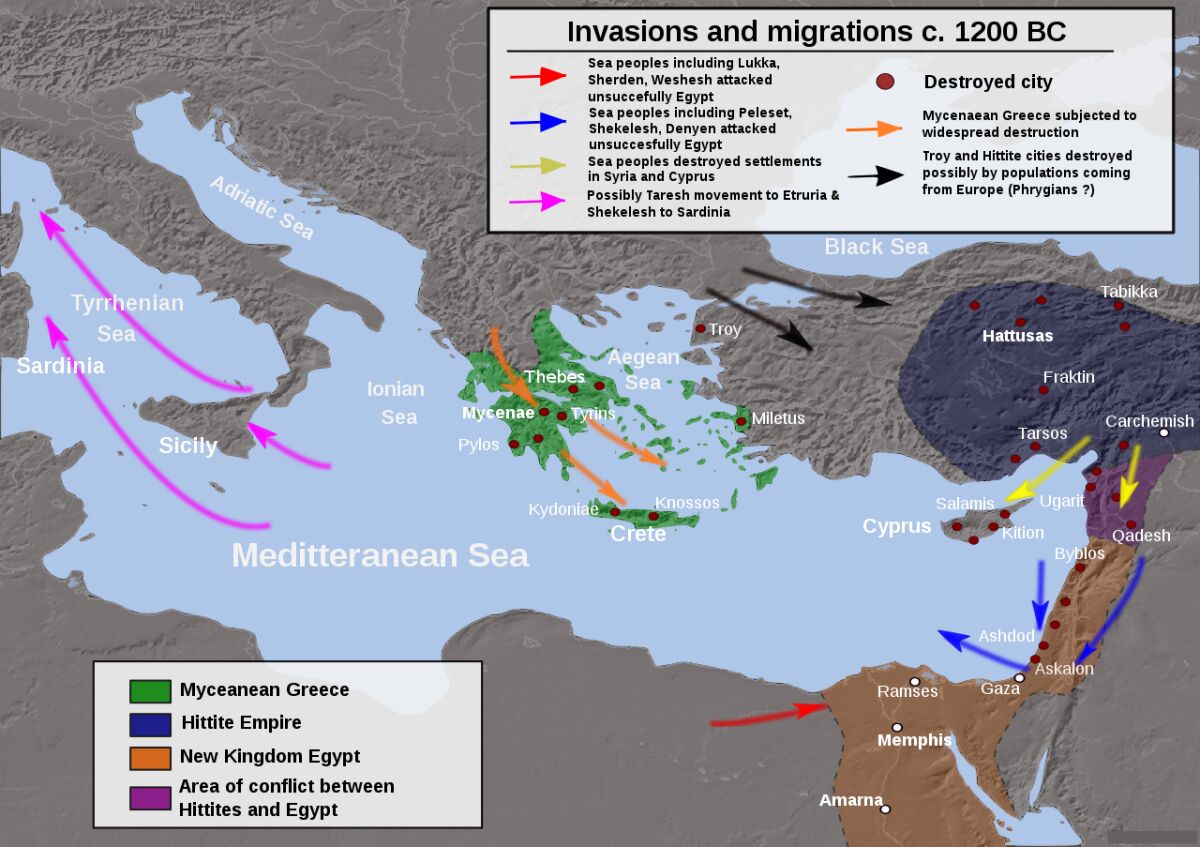

This fits with the wider historical picture. At the start of this period, a Hittite ruler wrote to the 13th-century Pharaoh Ramses ii, “I have no grain in my lands.” (The Hittite empire spanned from Syria into modern-day Turkey.) The following pharaoh, Merneptah, noted grain shipments being sent to “keep alive the land of Hatti” (circa 1210 b.c.e.).

This time period from the 13th to 12th century is known for the mysterious “Bronze Age Collapse”—the upheaval of civilizations around the eastern Mediterranean. The Hittite empire collapsed. The Egyptian empire became greatly diminished, never to rise to its earlier days of prominence. Greece emerged entirely different. Wars broke out, migrations were rife, a strange “sea people” began marauding throughout the region, and the Philistines invaded and settled in large numbers alongside Israel. The reason for this upheaval and ensuing “dark age” has long stumped historians. But could it have been exacerbated—perhaps even caused—by a devastating regional famine, between 1250 and 1100 b.c.e.? And could it be the reason Elimelech’s family moved east toward the plains of the Middle East—away from the Mediterranean region?

A Long, Hard Famine

The Bible only describes one famine in the Levant between the time of the patriarch Jacob (circa 1700 b.c.e.) and King David (circa 1000 b.c.e.)—and that is the famine mentioned in the book of Ruth. The setting of this book is during the latter part of the judges period; the genealogy of chapter 4 locks it into the exact same time period as the above-discovered famine—particularly toward the late 12th century, or end of the famine period.

The Bible doesn’t describe exactly how long the famine lasted, apart from the fact that it did last a long time. The famine is spoken of more generically as taking place “in the days when the judges ruled.” The biblical judges period spanned from the 14th to the 11th centuries b.c.e.—roughly 350 years (see Judges 11:26)—so this famine appears to have taken up a significant percentage of this attributed period.

The migration of Elimelech’s family into the land of Moab due to the famine lasted a full 10 years—up until it was “heard in the field of Moab how that the Lord had remembered His people in giving them bread” (verse 6). Interestingly, the tau researchers discovered that at the end of the “drought” sedimentary layers, there was evidence of a wet recovery period.

But the biblical famine had been long and hard—and there is further indication of this, long before the migration into the land of Moab. The sons of Elimelech and Naomi, who would have been young adults at the time of their journey, were named Mahlon and Chilion. Mahlon means “sick” (from a root indicating weakness), and Chilion means “wasting away,” or “pining”—both names that would fit well with the birth of malnourished children in a famine setting. Partway through their sojourn, both young men died, along with their father—leaving to widowhood the matriarch Naomi and their wives, Ruth and Orpah.

Many people know the period of the judges as a violent, sinful time of upheaval for the fledgling nation of Israel. A time of constant rebellion, wars, foreign oppression and slavery. The backdrop of famine throughout a large part of this period is perhaps overlooked—but it should not be surprising. In the “blessings and curses” chapters of Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28, God told the Israelites before they entered the Promised Land that if they rebelled, they would face, among other things, brutal famines. Some of the specifics in these prophetic chapters are remarkable. Deuteronomy 28:40 states that, among the curses, the rebelling people would have olive trees—but that they would lose the fruit of them. (Remember, the tau pollen samples showed that during the famine, there was a dry-climate surge in olive tree farming.) Even the root word for the name Chilion is found in Deuteronomy 28:65—and the root word for Mahlon can be found in the following chapter, continuing to describe the curses (Deuteronomy 29:21).

The tau findings, then, corroborate the biblical account of an enduring famine event through the judges period—as also mentioned in the surrounding ancient texts. (It is ironic that the research was led by the famously “anti-David” Professor Finkelstein—given that the book of Ruth is key in setting up the ancestry of King David.)

Some scholars speculate that the book of Ruth was conjured up in the fifth century b.c.e., as a counter-narrative to Nehemiah’s strict rules against intermarriage (Nehemiah 13; though the “intermarriage” question of Ruth is another subject entirely). But evidence shows otherwise. Outside of the first five books of the Bible (the Torah), the Hebrew writing in Ruth is one of the oldest styles found anywhere in the Bible—if not the oldest. The repeated use of very early words and spelling would be extremely unusual—if not virtually impossible—for a postexilic writer to accurately represent. Thus it naturally fits a very early period of writing (it is traditionally attributed to the Prophet Samuel). As one leading critic admitted, the ancient stylistic “purity” of the book sends it “decidedly to the pre-exilic period.”

And now, from the smallest of “artifacts,” we have evidence for the geopolitical situation of the book of Ruth—the account fitting in precisely with the secular historical dating of a region-wide catastrophic famine. A famine that drove Elimelech east to the land of Moab, where Naomi met Ruth—and three generations later, Israel’s greatest king was born.