The account of Boaz and Ruth, which took place during the time of the judges, is one of the great love stories of the Bible (against the backdrop of some interesting archaeological corroboration for the period). But directly prior to this pair was another biblical relationship, given only the briefest of mentions—the parents of Boaz.

Have you heard about Salmon and Rahab?

In this article, we’ll look into the short historical mention of this enigmatic pair.

Boaz, Son of Salmon—and Rahab?

Only a handful of verses mention a patriarch named Salmon, noting that he was the father of Boaz (i.e. Ruth 4:21; 1 Chronicles 2:11). But what about Rahab? This isn’t mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. But it is mentioned in the first-century New Testament book of Matthew, which gives the following genealogical record: “Salmon begot Boaz by Rahab, Boaz begot Obed by Ruth …” (Matthew 1:5; New King James Version).

The link to one and the same Rahab of the book of Joshua is clear. That’s because in the 14 generations listed in this passage from Abraham to David, only four biblical women are highlighted—and they are all key figures in the Hebrew Scriptures: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and Bathsheba. This must have been the Rahab—certainly not another random woman of the same name, during the same judges period, contemporary with Salmon, but not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

The Greek wording in this passage makes this evident: namely in the form of the definite article before Rahab’s name. The passage could be translated as “Salmon begot Boaz by that Rahab.” Benson’s Commentary notes: “[T]here was no other of that name, especially of that age, of whom the compiler of the table could possibly suppose his reader to have any knowledge.”

Of the source of this genealogy, Gill’s Exposition commentary says: “This [Matthew] had from tradition, or from the Jewish records …. [T]he Jewish writers … own that Rahab was married to a prince in Israel.”

Indeed, such writers of later centuries speculated that that prince may have been Joshua. Still, the first century c.e. genealogy of the Jewish publican Matthew is the earliest existing genealogy clearly naming Rahab’s husband—as the “prince” Salmon.

Prof. Richard Bauckham notes that out of Matthew’s entire genealogy, only three names differ from the Greek form used in the third-second century b.c.e. Septuagint (lxx)—two of them being Rahab and Boaz. As such, he writes that this “strongly suggests that at this point the genealogy has recourse to a tradition independent of the [Greek] lxx” (Tamar’s Ancestry and Rahab’s Marriage, 1995).

Bauckham continues, addressing the lack of other known, existing genealogies making mention of Rahab as mother of Boaz, stating that it does “not mean that Matthew was original in making Rahab an ancestor of David. For the inclusion of Rahab in the genealogy of the Messiah to have carried any weight … her marriage [to Salmon] must surely have been an already accepted exegetical tradition … the tantalizingly fragmentary Qumran text 4Q549 [circa 2nd century b.c.e.], which evidently concerned the genealogies of members of the tribes of Judah and Levi in the Exodus period and after, shows that there certainly were genealog[ies] … which have now been lost.”

For his part, Bauckham posits that Matthew’s reference to Rahab and Boaz was directly derived from the Hebrew Bible—notably, a re-translation of 1 Chronicles 2, which describes descendants of “Salma” (another version of the name Salmon; verses 11, 51, 54) in the very same verses as being also part of the “house of Rechab” (verses 54-55; the name Rechab spelled slightly different to Rahab in Hebrew and Greek, but with a similar sound—רכב and רחב, Ρηχαβ and Ραχαβ). For more on this, and on the broader subject of Rahab’s cultural identity, see our article “Was Rahab Really a Canaanite?”

Fall of Jericho—Rise of Rahab

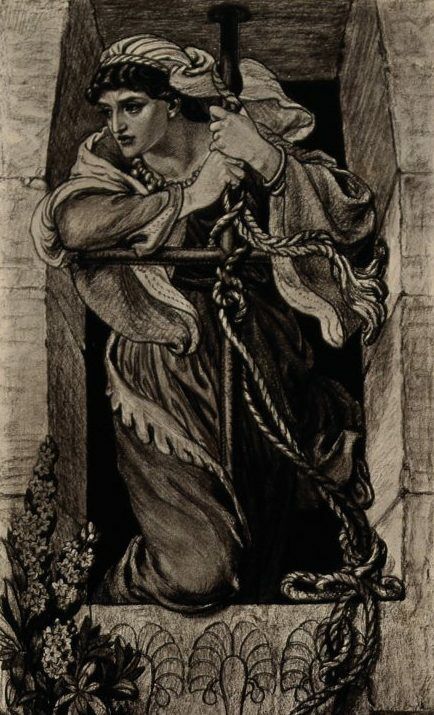

The account of Rahab the harlot of Jericho is famous—how she hid the two Israelite spies in her home, helped them to escape, and asked for Israel to preserve her and her family when they conquered the land. “I know that the Lord hath given you the land, and that your terror is fallen upon us, and that all the inhabitants of the land melt away before you,” she told the spies as she hid them from the Canaanites within the city that were searching for them. “[F]or the Lord your God, He is God in heaven above, and on earth beneath” (Joshua 2:9, 11).

“And the men said unto her: ‘Our life for yours, if ye tell not this our business; and it shall be, when the Lord giveth us the land, that we will deal kindly and truly with thee’” (verse 14).

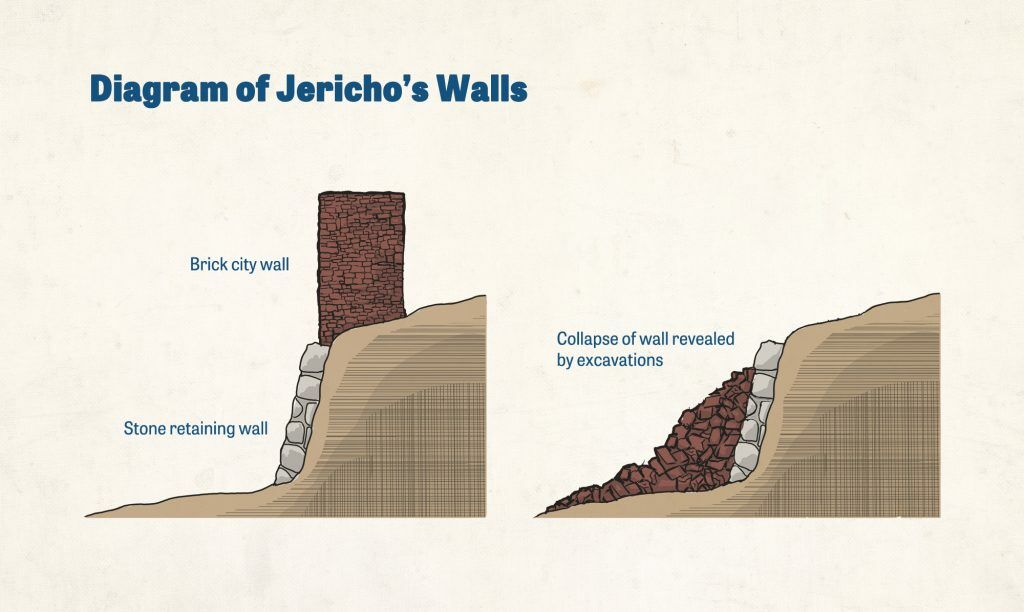

The spies safely returned to the Israelite encampment, informed Joshua of all that had occurred, and four chapters later the Israelites marched to Jericho and surrounded the city. After parading around the city for seven days, a miraculous earthquake took place, and the walls “fell down flat”—all except for Rahab’s apartment (which made up a part of the casemate wall). Remarkably, evidence of these collapsed walls, the post-destruction burning of the city, and even a small remaining part of the casemate wall (Rahab’s house?)—has been found at Tel Jericho, dating to this same period in biblical chronology. For more about this, read our article “Uncovering the Bible’s Buried Cities: Jericho.”

The text reveals that Rahab was relatively young at this point: No children are mentioned, and there is a repeated emphasis on her parents. After Jericho was overthrown, “the young men the spies went in, and brought out Rahab, and her father, and her mother, and her brethren [brothers and sisters], and all that she had, all her kindred [relatives] also they brought out; and they set them without the camp of Israel” (verse 23). No further mention of Rahab’s extended family is described in connection with Israel—it is possible that they chose to go their own way.

Rahab, however, didn’t. The first-century historian Josephus wrote: “And when she was brought to him, Joshua owned to her that they owed her thanks for her preservation of the spies: so he said he would not appear to be behind her in his benefaction to her; whereupon he gave her certain lands immediately, and had her in great esteem ever afterwards” (Antiquities, 5.1.7).

“[A]nd she dwelt in the midst of Israel, unto this day …” (verse 25). The Hebrew for in the midst is often used to refer to the literal bowels of a creature, and even babies in the womb (Genesis 25:22)—thus, she continued to dwell right in the core of the nation. The word dwell can also be used in the sense of marriage. Thus, a dwelling in the midst—or more figuratively, marrying into the princely core of the nation.

Again, the Bible gives no particulars about what happened next. Ellicott’s Commentary states: “[R]ecords are silent as to the marriage of Salmon with the harlot of Jericho. When they were compiled it was probably thought of as a blot rather than a glory; but the fact may have been preserved in the traditions of the house of David.” (Indeed, to this day many newborn girls are given the names of famous women in the Bible, like Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel and Ruth—but despite her righteous act, how many Rahabs do you know?) But as to the identity of Salmon, several commentaries make a fascinating suggestion. Ellicott’s continues: “It has been conjectured that Salmon may have been one of the two unnamed spies whose lives were saved by Rahab, when he was doing the work which Caleb [of the same tribe] had done before him” (emphasis added).

Bauckham similarly notes: “So [Rahab] must have married a suitably illustrious Israelite…. That she married [Salmon] would be … not too surprising. As the son of Nahshon, he would have been supposed to be a very prominent member of the tribe of Judah. Possibly the tradition that he married Rahab was linked to a tradition that he was one of the spies in Jericho” (ibid).

The Spy Who Loved Me

It’s a plot ripe for a Hollywood movie (forgive the Bond reference). Spy scopes out enemy territory, harlot saves spy, city is conquered, spy returns to rescue her, they marry and become one of the core upstanding families in the nation.

Salmon himself was evidently a young man at the time; besides Joshua and Caleb, all Israelites 20 and older at the time of the Exodus died in the wilderness (Numbers 14; Joshua 6:23).

In Joshua 2:12, Rahab says to the two spies: “Now therefore, I pray you, swear unto me by the Lord, since I have dealt kindly with you, that ye also will deal kindly with my father’s house—and give me a true token.” This word “token” can generally mean a “sign”—but it is also used in the Bible as a sign of a covenant, similar to a ring as a “token” of a marriage covenant. (Perhaps this “sign” ended up being taken quite literally?)

One of the two spies spoke up and informed Rahab, “Our life for yours, if ye tell not this our business; and it shall be, when the Lord giveth us the land, that we will deal kindly and truly with thee” (verse 14). Those are some rather dramatic and impassioned words for a complete stranger in an enemy city—again, perhaps there was more to this than meets the eye.

Was Salmon one of the two spies? Dr. Herbert Lockyer (one of the most quoted Bible expositors of the 20th century), thought so. He wrote in All the Women of the Bible: “Rahab is referred to as being the wife of Salmon, one of the two spies she sheltered. In turn, she became the mother of Boaz. … As the result of her marriage to Salmon, one of the two spies whom she had saved, who ‘paid back the life he owed her by a love that was honourable and true,’ Rahab became an ancestress in the royal line.”

As the Israelites stormed Jericho after the walls came down, “… Joshua said unto the two men that had spied out the land: ‘Go into the harlot’s house, and bring out thence the woman, and all that she hath, as ye swore unto her’” (Joshua 6:22).

I can’t help but think Joshua was especially telling a certain spy, Go and get her!

A Salmon by Any Other Name …

There’s another side to all of this. Salmon’s name isn’t just peculiar for its English translation; the use of the name in the original Hebrew language is truly befuddling.

It’s not entirely unusual for a handful of names in the Hebrew Bible to be spelled differently here or there. David, for example, is often spelled in Hebrew Dvd; however, in scriptures written at a much later date (i.e. Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah, written during the Persian period) the spelling changed somewhat to the equivalent of Dvid.

With Salmon, it’s altogether different. Virtually every time he is mentioned, his name is spelled differently—whether or not it features in a different book of the Bible or in the following verse!

Ruth 4:20 names him Salmah (“Slmh”). The very next verse, Ruth 4:21, names him Salmon (“Slmwn”). 1 Chronicles 2 names him slightly differently again, as Salma (“Slm’”). The Septuagint variously translates the name Salman, Salmon, and Salomon. Matthew names him Salmon.

The slight change in spelling between Ruth 4:20 and 21 may simply denote that the patriarch was named “Salmah” at the start of his life but his name changed to “Salmon” later on (“-on” is a fairly standard Hebrew suffix). Name modification has Bible precedent: For example, Abram to Abraham, Sarai to Sarah. 1 Chronicles 2:11 apparently chose to use a later version of the initial name.

His name is typically taken to mean garment, mantle or raiment. It strikes as an unusual thing to call your child—but one possibility is that it is a reference to the stunning miracle of the time period, when all the Israelites’ garments lasted without wear throughout the 40-year sojourn in the wilderness (Deuteronomy 29:4).

Another possibility, though, could link directly to the story of Rahab: The name Salmah is tied by Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance to a similar root word, Simlah. This word is used in Deuteronomy 21, a passage describing the procedure for what to do if any of the Israelite soldiers “seest among the captives a woman of goodly form, and thou hast a desire unto her, and wouldest take her to thee to wife” (verse 11). A central term in the process is the Simlah (garment) of her captivity (verse 13). Could this be a link to Salmon/Salmah and Rahab—perhaps not so much a fixed personal name as a symbolic term?

Rahab’s Road to Redemption

Picking through the details of Rahab’s life story makes for interesting study and speculation—but it is nothing in comparison to the real purpose and meaning relayed in the biblical account about her. As Ryan Malone wrote in his article “The Faith and Salvation of Rahab”: “Rahab stands as a testament to life-saving faith. It was a faith manifested through works—works that required her to risk her life for God’s cause. That kind of faith takes a deep-rooted trust in God.”

“Rahab also stands as a testament to God’s forgiveness—and how to move forward and support God’s efforts despite a horribly sinful past” (ibid).

Rahab is praised in several passages of the Hebrew Bible. And she is likewise put on a pedestal in the New Testament, labeled alongside some of the greatest individuals in the Hebrew Bible.

There’s a lot that we don’t presently know about Salmon and Rahab. Nevertheless, great individuals like Boaz don’t just appear out of nowhere. Some of the greatest testimony to an individual is that of their children—in this case, the “mighty man of valor,” Boaz. And a genealogical preservation into the world’s greatest royal lineage—the “everlasting throne” of David.

For more on the subject of Rahab, take a look at the following articles: