The story of Rahab and the spies, Jericho’s walls that “came tumbling down,” and the saving of Rahab’s family is one of the most well-known in the Bible. Some may be surprised to learn that it is a story for which there is some remarkable archaeological corroboration.

But was Rahab really a harlot—a prostitute?

The answer seems obvious. Joshua 2:1 says the two spies sent by Joshua into Jericho “came into the house of a harlot whose name was Rahab.” Joshua 6:17 further confirms: “[O]nly Rahab the harlot shall live, she and all that are with her in the house, because she hid the messengers that we sent.” Finally verse 25 states that “Rahab the harlot, and her father’s household, and all that she had, did Joshua save alive.”

This profession has been widely attributed to Rahab and is the sense rendered by the vast majority of translations. However, an alternative view has persisted: that Rahab was actually an inn-keeper or something other than a prostitute.

In the first of this two-part study on Rahab’s identity, we’ll examine the question of her profession: Was she really a prostitute?

The Case for Rahab as Inn-Keeper (or Anything Else)

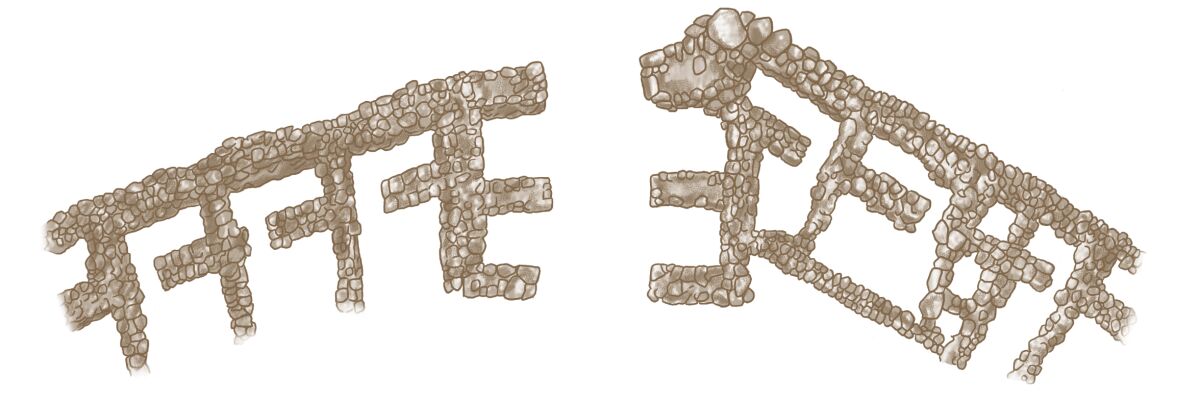

The Hebrew word used to describe Rahab is zonah (זונה). This is a word widely recognized to mean a harlot or prostitute. (It’s also a curse word that crops up frequently in modern Hebrew—בן זונה—hardly meaning “son of an inn-keeper.”) Yet those highlighting Rahab’s profession simply as an inn-keeper highlight an alternate sense of the word, to mean just that.

In his September-October 2013 Biblical Archaeology Review article “Was Rahab Really a Harlot?”, Prof. Anthony Frendo wrote:

It is true that the text identifies Rahab as a zônāh, a prostitute (Joshua 2:1), but she actually comes across more as a landlady or innkeeper than a prostitute. And the first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus tells us that Rahab kept an inn (katagōgion in Greek).

Was she an innkeeper or a prostitute? Or perhaps both?

The consonants that make up the word “prostitute” in Hebrew are znh (זנה), which happen to be identical to the consonants of the Hebrew word for a female person who gives food and provisions. And indeed, the biblical text does not make or imply any negative comments regarding Rahab’s profession. Josephus’s information that Rahab kept an inn could well be an old tradition, although this does not necessarily negate the fact that she could also have been a prostitute. Josephus may have preserved the innkeeper tradition in conjunction with the folk memory of a local group who had been spared by the incoming Israelites.

Certainty eludes us.

An example of a staunch proponent against the identification of Rahab as a prostitute is the late Christian author Isabel Hill Elder, who in 1957 published a book titled Far Above Rubies—a biographical commentary on the lives of prominent women featured in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, from Sarah to Claudia. In Chapter 7, Elder wrote:

We shall now … try to ascertain how the obnoxious appellation, “harlot,” came to be attached to her. …

[In the translation of] Ferrar Fenton … Rahab is put down as an “innkeeper” and by [Myles] Coverdale as a “taverner.” These are but brave attempts to clear the fair name of Rahab from the objectionable term “harlot.” “Innkeeper” and “taverner,” however, convey no historical truth, for in the East the inns or khans had neither host nor hostess.

Elder proposes something else entirely—that the term used for Rahab should simply be rendered as “widow”:

In Eastern languages, the same word is often used for “harlot” and “widow” as, for instance, in the Urdu language. The same word would appear to describe a woman no longer a virgin, but without a husband, whether she had been legally married or not. It is a striking fact that in the Authorized [King James] Version of the Scriptures, Jeroboam’s mother, Zeruah, is recorded as “a widow woman” (1 Kings 11:26) while in the Septuagint the word used is “harlot.”

If the translators had inserted “widow” in the margin opposite Rahab’s name in Joshua chapter 2, it would at once have been clear to the reader that “harlot” and “widow” were interchangeable terms.

The first-century c.e. Jewish historian Josephus refers to Rahab only as an inn-keeper, making no reference to any other occupation. “[The spies] were in the inn kept by Rahab”; the Israelites later “saved alive Rahab, with her family, who had fled to her inn” (Antiquities of the Jews, 5.1.2, 7). And certain later rabbinic texts emphasize Rahab’s role as an inn-keeper.

End of story, then? Was Rahab’s association with prostitution really so tenuous all along? Not quite.

The Case for Rahab as a Prostitute

The sense of the Hebrew word zonah, anciently as well as modern, is synonymous entirely with harlotry. The word as rendered, zonah (זונה), is explicit—as Frendo himself notes, writing, “It is true that the text identifies Rahab as a zônāh, a prostitute ….” It is only reassigned meaning by artificially deconstructing the word.

In the nearly 100 examples of this word used throughout the Bible, harlotry is the express and explicit sense given throughout. Examples of the use of this Hebrew word include the raped Dinah being treated as “a harlot” (Genesis 34:31); Judah mistaking Tamar for “a harlot” and fornicating with her (Genesis 38:15); repeated metaphorical references to Israel “whoring” after other gods; warnings to “not prostitute thy daughter, to cause her to be a whore” (Leviticus 19:29; King James Version); the Israelites in the wilderness “commit[ing] harlotry with the daughters of Moab” (Numbers 25). The book of Ezekiel goes into graphic detail in the context of this term, in symbolically describing the behavior of Israel and Judah among foreign powers (Ezekiel 16).

Indeed, despite objections to the contrary, not a single positive example of the biblical use of this term, as anything other than referring to harlotry, can be made. As such, the McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia concludes that, despite certain later attempts to sanitize Rahab’s former life, “we must be content to take facts as they stand, and not strain them to meet difficulties; and it is now universally admitted by every sound Hebrew scholar that זונה means ‘harlot,’ and not ‘hostess.’ It signifies ‘harlot’ in every other text where it occurs, the idea of ‘hostess’ not being represented by this or any other word in Hebrew, as the function represented by it did not exist.”

To this end, Elder’s opinion that the term זונה should be rendered “widow” is unusual, given that there is another biblical term signifying this word—and it is listed alongside the word for harlot/prostitute in Leviticus 21:14: “A widow, or one divorced, or a profaned woman, or a harlot, these shall he not take; but a virgin.” Elder’s appeal to 1 Kings 11:26 is also unusual, given that the Hebrew word for “widow” here is not zonah (זונה) at all but is rather the entirely different almanah (אלמנה), the standard Hebrew word for “widow” (the same word in Leviticus 21:14). Her assertion that “in the Septuagint the word used is ‘harlot’” (thus making the case that the words for “widow” and “harlot” are interchangeable) is at best misleading. That’s because the Greek Septuagint (lxx) also very clearly uses the term “widow” to describe Zeruah, Jeroboam i’s mother, in 1 Kings 11:26 (chira, χήρα). It is only in another passage entirely—1 Kings 12:24b—that the lxx adds to the text an additional detail not present in the Hebrew Bible, that Zeruah was a harlot (porne, πόρνη)—the use of such terms logically implying that the lxx authors recognized her as both a widow and a harlot. But the Septuagint in no sense renders these terms as interchangeable.

The earliest known translation of the Hebrew scriptures is the Greek Septuagint, the Torah portion of which originally was translated during the third century b.c.e., with the later books generally attributed to the work of translators during the second century b.c.e. And the lxx is entirely unambiguous in its terminology for Rahab: It uses the word porne (πόρνη) to refer to her profession. This is a Greek term unequivocally and only referring to harlotry, prostitution (and yes, this word is related to the modern term “pornography,” from the Greek porno-graphos—literally, “writing about prostitutes”—although the modern meaning has clearly changed somewhat). Thus, to these early, Hebrew-speaking translators, the meaning was clear and unambiguous—Rahab was a prostitute.

This is also the unequivocal, and unambiguous, identification given in the New Testament. Rahab is mentioned by profession twice in the New Testament, by two different authors (Hebrews 11:31; James 2:25), with the same unambiguous Greek term used in the Septuagint—porne (πόρνη).

Elder actually quotes from these New Testament passages in her chapter on Rahab—but on both occasions she omits “the harlot” in her quotations entirely and without explanation, with ellipses (“…”). And while Frendo’s article leaves the question of Rahab’s profession as “uncertain,” it is unusual that his article goes on to highlight what he sees as the Septuagint’s more accurate original account of the style of Rahab’s dwelling place—while omitting entirely the Septuagint’s unambiguous description of Rahab’s profession.

As for Josephus: His passing references to Rahab’s “inn” hardly negates her profession as a prostitute. As Josephus’s translator, William Whiston, comments in a footnote to this passage: “It was indeed so frequent a thing, that women who were innkeepers were also harlots, or maintainers of harlots.” Could Rahab have been an innkeeper and a harlot? It is certainly possible. But there is far less ambiguity with her identification as a harlot than as an inn-keeper or anything other than a harlot. And to this end, despite certain later rabbinic texts mentioning Rahab as an inn-keeper, this view—that she was a harlot—remains the common understanding in Judaism, with the Talmud providing additional detail on the subject.

Proponents for Rahab as simply an inn-keeper, then, are required to highlight ambiguity as their best evidence and must show why unambiguous passages (i.e. in the Septuagint and New Testament) must be wrong—as well as why the universal use of the term in the Hebrew Bible must not apply in this particular case. Yet the position for Rahab as a prostitute is far simpler—to hold that all such references are consistent and correct.

What About the Spies?

But what about the Israelite spies? Their mission, which brought them into the dwelling of Rahab, is sometimes used as a basis for arguing that Rahab was an inn-keeper. In the words of Cruden’s Concordance (as quoted by Elder): “Some think she was only an hostess or inn-keeper; and that this is the true significance of the original word. Had she been a woman of ill fame, say they, would Salmon, a prince of the house of Judah, and one of the Saviour’s ancestors, have taken her to wife, or could he have done it by the law? Besides, the spies of Joshua would hardly have gone to lodge with a prostitute, a common harlot; those who were charged with so nice and dangerous commission.”

Thus, surely the spies—if they were to be considered above reproach—must have checked themselves into a reputable establishment.

The McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia answers succinctly (emphasis added):

There were no inns; and when certain substitutes for inns eventually came into use, they were never, in any Eastern country, kept by women. On the other hand, strangers from beyond the river might have repaired to the house of a harlot without suspicion or remark: the Bedawin from the desert constantly do so at this day in their visits to Cairo and Bagdad. The house of such a woman was also the only one to which they, as perfect strangers, could have had access, and certainly the only one in which they could calculate on obtaining the information they required without danger from male inmates.

Thus, this choice of location for extracting information only becomes entirely logical.

Additional Details

There are several additional, often overlooked, circumstantial details pointing to Rahab’s profession as a prostitute. Several of these are highlighted in Prof. Frank Spina’s The Faith of the Outsider: Exclusion and Inclusion in the Biblical Story.

One point he brings up is the name applied to her, Rahab (רחב)—an unusual name found nowhere else in the Bible for any other individual. The meaning of this name has led many commentators to wonder if it is a reference to her sexual profession. Spina summarizes: “Readers who understand Hebrew will immediately wonder whether Rahab’s name is meant to be risqué: In etymological terms, Rahab’s name connotes something ‘broad’ or ‘wide,’ hardly bold in describing a path, say, but having an entirely different sense when applied to a woman engaged in the ‘world’s oldest profession.’ … [G]iven the explicit description of Rahab as a prostitute … and the general meaning ‘broad’ or ‘wide,’ which is sexually suggestive for a woman of this métier, the name is almost surely to be taken as a not too subtle symbol of both her occupation and reputation.” (Still, there is an alternative explanation for Rahab’s name, which will be mentioned in part two.)

Another point is the dialogue in the Joshua 2 account. This is hard to pick up on in translation, but Spina highlights “a number of sexual innuendoes” buried in the discourse. He gives the conversation between Rahab and the king of Jericho’s men as an example: “When the king’s agents demand that Rahab produce the spies … their language is lewd and crude: ‘Send out the men who entered you … er, who entered your house.’ The combination of the Hebrew verb for ‘enter’ and the preposition ‘unto’ sometimes means to approach someone with sexual intent (e.g. Judges 15:1). So the king’s agents incorporate a well-aimed barb into their insistence that Rahab bring forth the men they believe she is hiding.”

Another interesting feature in the story is Rahab’s scarlet-colored material, which she used to lower the spies from her window (and which later served as a sign in the window for Rahab and her family to be spared). The color scarlet has long been famously linked with harlotry. (Revelation 17:1-5, for example, famously describe the symbolic, scarlet-adorned “Great Whore”; also, the color serves as a symbol of sin itself—e.g. Isaiah 1:18.) This is, of course, not the only symbolism of the color. However, it is surely more than coincidental that in the setting of Rahab’s house, the only color featured in the account—prominently, at that—is scarlet.

Another notable feature of the story is the positioning of Rahab’s house. The language has long been recognized as peculiar—a house located in the city wall. Joshua 2:15 describes: “Then she [Rahab] let them [the two spies] down by a cord through the window: for her house was upon the town wall, and she dwelt upon the wall” (King James Version). The Hebrew word for “upon” is actually in. Thus, the last half of this verse more literally reads, “her house was in the town wall, and she dwelt in the wall.” Of course, such phraseology does not at first seem to make much sense. Yet archaeological work has revealed the presence of casemate walls surrounding ancient cities in the Levant—walls with hollow, chamber-like interiors, that could be filled in in the event of war. During peacetime, casemate chambers could be used for storage—or even for dwelling.

A peripheral, casemate chamber-integrated dwelling seems hardly the place for a well-trafficked Best Western—but such a fringe dwelling would make sense as the abode of a city prostitute.

A final point is the emphasis of praise for Rahab’s righteous deeds. This emphasis works best in juxtaposition to her former profession. As the New Testament book of James highlights: “In the same way, was not even Rahab the prostitute considered righteous for what she did when she gave lodging to the spies and sent them off in a different direction?” (James 2:25; New International Version; see also Hebrews 11:31). Even a prostitute was considered righteous—other translations state that she was “justified”—by her deeds. Joshua 6 also contains implicit regard for Rahab’s actions.

Was Rahab, then, really a prostitute? The answer can only be—from the biblical text—a resounding “Yes.” Was she also an inn-keeper? Perhaps, in some form—although this is not nearly as obvious (and if anything, this may have more likely been a later tradition designed to paper over Rahab’s unseemly profession).

But was she really a Canaanite? This is where things get particularly interesting. This point of cultural identity we’ll examine in part two.