He is known as one of the Holy City’s greatest rebuilders. Yet for millennia, evidence of his existence has remained buried beneath Jerusalem’s dust. What did remain of him was a story—an entire biblical book devoted to his heroic deeds. For most, of course, that wasn’t proof enough of his story.

Yet over the past decades, more and more evidence has been uncovered, unraveling the fascinating story of this noble man. While his name itself still hasn’t turned up in archaeological excavations, the names of several of his biblical contemporaries have. And notably, his defining work has been partially excavated—his wall, built in 52 days.

Science is uncovering not only mere snippets of the Bible, but entire stories. As with our previous articles on King David, King Hezekiah, the Prophet Jeremiah and the Prophet Elisha, we now examine the life of Nehemiah.

The Cupbearer and a Gracious King

We are introduced to Nehemiah in the Persian royal court circa 445 b.c.e. The Bible describes him as a royal servant to king Artaxerxes. This king, known by his full name Artaxerxes I Longimanus, is heavily attested to in archaeology. His father was King Xerxes, the probable husband of Queen Esther. (Artaxerxes’s mother was Amestris. The jury is still out on whether this was Queen Esther—Amestris has a form similar to Esther.) King Artaxerxes’s ascension to the throne was under less-than-pleasant circumstances. Xerxes was murdered, and Xerxes’s eldest son, Darius, was blamed. Artaxerxes thus killed Darius and assumed the throne. However, the real murderer had been the vizier Artaban. This wretched man next attempted to kill Artaxerxes. His plan was leaked, however, and Artaxerxes killed Artaban and his family.

Aside from this turbulent beginning, however, Artaxerxes’s reign was generally peaceful. He was described by the ancient Greeks as magnanimous and kind—and this is exactly the kind of man portrayed in the book of Nehemiah.

Nehemiah’s role in the Persian administration was that of cupbearer (Nehemiah 2:1). Yet this was not a peon role. Ancient cupbearers were of high rank. Their job consisted of serving beverages in the king’s court. This job demanded a high level of trust because of the ease of poisoning the king through drink. A cupbearer would sometimes be required to first drink the beverages, a fail-safe against the king receiving any poison. While the job carried some risk, the pay would have been high, as was the level of influence.

While serving the king in his palace at Shushan (discovered, excavated and known today as Susa), Nehemiah received word from his brother Hanani, who had just returned from visiting Jerusalem. Hanani reported that the city still lay in utter ruins and the people remaining there were continually oppressed. This stirred Nehemiah to pray for forgiveness for himself and his people, and for help when he approached King Artaxerxes about leaving his post and making the journey to his beloved city.

Around four months later, Nehemiah had a course-changing exchange with Artaxerxes. The king, noticing Nehemiah’s downcast disposition, asked him what was wrong. (Seeing a cupbearer troubled—the one intended to protect you from attempts on your life—surely would have been cause for concern!) Nehemiah explained the degenerate state of “the place of my fathers’ sepulchres.” The king immediately asked what Nehemiah wanted to do.

“Then the king said unto me: ‘For what dost thou make request?’ So I prayed to the God of heaven. And I said unto the king: ‘If it please the king, and if thy servant have found favour in thy sight, that thou wouldest send me unto Judah, unto the city of my fathers’ sepulchres, that I may build it.’ And the king said unto me, the queen also sitting by him: ‘For how long shall thy journey be? and when wilt thou return?’ So it pleased the king to send me; and I set him a time” (Nehemiah 2:4-6).

Thus Nehemiah departed from King Artaxerxes and (most likely) Queen Damaspia to begin an initially 12-year journey that would change history.

Arrival in Jerusalem, Enemies

Nehemiah acquired permission to get building materials from the king’s forest, and he was also given a military escort. He arrived safely in Judah and, along with a few chosen men, stole away at night to view the state of Jerusalem’s walls. The city was just as Hanani had described—in fact, such was the extent of the debris that the horse Nehemiah rode upon couldn’t continue.

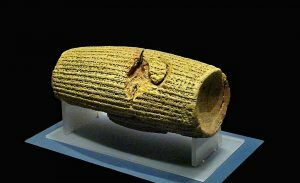

After viewing the destruction, Nehemiah gathered the rulers, priests and laymen and informed them of his plans to rebuild the city. Remember at this point that the second temple had already been built (Ezra 6). King Cyrus had decreed nearly a century before that the conquered Jews would be allowed to return to their homeland to rebuild the temple. A similar-sounding decree from King Cyrus has been unearthed, written to the conquered Babylonians—of course, this is the famous Cyrus Cylinder (it shows a precedent for Cyrus’s rare and unusual actions).

But by Nehemiah’s time, Jerusalem still lay completely open to attack. It didn’t have a city wall, and its gates had been utterly destroyed. Nehemiah intended to change that by exerting a massive rebuilding effort. Already, however, the enemies were stirring.

Rulers of the surrounding lands relished the fact that Jerusalem and Judah lay in utter ruin. They mocked Nehemiah for even thinking he could rebuild Jerusalem. The rebuilders of the temple had faced similar opposition.

One interesting neighboring ruler of that time was the governor Tatnai (Ezra 6). His existence has been verified through archaeology—known by the slightly longer name Tattenai. His name has been preserved on a number of cuneiform tablets. One tablet in particular, dated precisely to June 5, 502 b.c.e., mentions “Taattanni, governor of Across-the-River.” Interestingly, the title given him in the Bible directly parallels this: “Tatnai, governor on this side the river.” According to the biblical account, he was not necessarily opposed to the Jews rebuilding the temple—but he had written to the Persian King Darius (also identified though archaeology) to see if the Jews had indeed been given permission to rebuild.

In Nehemiah’s time, though, the opposition was fiercer. The chiefs of the land—namely, Sanballat, Geshem and Tobiah—rose up, initially in ridicule, but also for more bloodthirsty reasons.

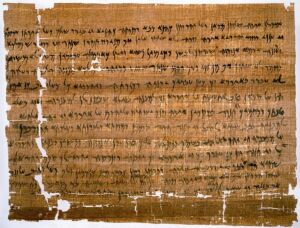

Sanballat the Horonite has been verified through archaeology. Sanballat was a governor of Samaria. He is mentioned in a fifth-century b.c.e. papyrus, along with a possible mention on a damaged bulla. Geshem the Arabian has been discovered by archaeology with near certainty: The name “Geshem/Gashmu, king of Qedar” has been found on a fifth-century b.c.e. bowl. Qedar was a significant kingdom in northwest Arabia, thus fitting with Geshem’s biblical description as “the Arabian.” (However, another possible candidate is Gashm of Dedan—also an Arabian location. It seems nearly certain that the first is the correct figure—see additional evidence further down—but this second figure must also be mentioned.) Tobiah remains elusive, archaeologically—though at least the use of his name has been proved, such as on the sixth-century b.c.e. Lachish letters (“Tobiyahu”).

“[T]hey laughed us to scorn, and despised us, and said, What is this thing that ye do? will ye rebel against the king? Then answered Nehemiah, and said unto them, The God of heaven, He will prosper us; therefore we his servants will arise and build: but ye have no portion, nor right, nor memorial, in Jerusalem” (Nehemiah 2:19-20).

The Wall Begins

Most of the persecution, though, would come later. The task of rapidly building Jerusalem’s wall officially began. Nehemiah 3 gives a detailed account of the various sections of wall assigned to various workmen. The chapter begins by describing the northernmost part of the wall surrounding the temple and traces the description of the wall counterclockwise around the city and back up to the northern temple position.

One part of this wall does need to be described. Because it has recently been discovered.

In 2007, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar led a team (including aiba Office Manager Brent Nagtegaal) to hurriedly excavate and repair a partially collapsing small tower within the City of David. The tower was believed to date to the Hasmonean period (second to first century b.c.e.). However, rather than making simple repairs, a six-week-long excavation began that radically re-dated the tower.

Because the tower could not be repaired safely, it was totally excavated. Beneath it were the remains of two large dogs, along with a wealth of Persian period pottery and assorted finds. Nothing from a later period was found—meaning that rather than being built during the Hasmonean period, the tower dated to the Persian period, fitting squarely within the time of Nehemiah. And it wasn’t just a tower that had been found. A connecting length of wall, also dating to Nehemiah’s time period, and exhibiting a particularly rushed nature of construction, was found.

A tower, a wall, hasty construction, the Persian period—it all fits squarely with the rebuilding work of Nehemiah. We can even speculate on who may have rebuilt this portion of the wall. Nehemiah 3:15-16 read:

And the fountain gate repaired Shallun the son of Colhozeh, the ruler of the district of Mizpah … unto the stairs that go down from the city of David. After him repaired Nehemiah the son of Azbuk, the ruler of half the district of Beth-zur, unto the place over against the sepulchres of David….

This section of wall was found skirting over the top of what today is the most discernable ancient feature of the City of David: the great Stepped Stone Structure. This massive, stepped pile of stones dates to the time of King David. Various features of the city of Jerusalem are mentioned as being built around it in Nehemiah 3; surely, a structure as domineering as this would not have failed to be mentioned. Thus, the Stepped Stone Structure must surely be these “stairs that go down from the city of David.” That means that this section of wall, as per the above verse, may well have been built by Shallun or more likely Nehemiah (a different Nehemiah from the main figure in the biblical book).

Tool in One Hand, Weapon in the Other

Nehemiah’s opponent Sanballat was infuriated by the progress on the city wall. Together with Tobiah, he decried the efforts of the Jews in front of the Samarian army. Together with the Arabians, Ammonites and Ashdodites, secret plans were made to launch a surprise attack against Jerusalem (Nehemiah 4:1-8).

The prayerful Jews, however, became aware of the plans. Under Nehemiah’s direction, a defensive force was mobilized to guard the builders. Shifts were taken and watchmen kept a sharp lookout. A system of alarm was devised. The threat of imminent war became so severe that the workmen carried a weapon in one hand and a construction tool in the other.

The foreign armies, once they realized their plans for a surprise attack were known, seemed to become less eager for war. But Nehemiah maintained strict military readiness. Opposition, though, was not only felt from outside sources.

Several of the Jewish leaders had been heavily taxing and overcharging their own countrymen, and at a time when food was scarce (Nehemiah 5). They were living richly while their people were suffering. Certain of the Jews’ children were even being sold into bondage due to the inhumane demands of their leaders. Once Nehemiah learned what was going on, he strongly rebuked the nobles and demanded that all debts to be lifted immediately. The nobles complied with his commands.

Nehemiah made a specific point, in his 12 years as governor, of not demanding the typical riches due to a governor (verse 15). He regularly gathered large numbers of people to feed at his own table.

Construction Ends, Dedication Begins

Seeing Nehemiah’s wall nearing completion, Sanballat and Geshem knew they would not be in a position to stop the Jews. Their attention turned to taking out the leader himself. They attempted to draw Nehemiah into various situations in order to at least discredit his authority, perhaps even kill him.

Sanballat sent several letters to try to unsettle Nehemiah. One of these letters is quoted in Nehemiah 6:6-7. There is an interesting thing about this letter: In a direct quote, Sanballat writes Geshem’s name as “Gashmu” (King James Version). He is referring to the same man; obviously, Geshem must have been the pronunciation of the Jews, and Gashmu the pronunciation of the northern Horonites, of which Sanballat was a descendant. Remember that the most likely candidate for the biblical Geshem is “Gashmu king of Qedar.” Here we see exactly the same rendering of the name, directly quoted in Sanballat’s correspondence, as has been found through archaeology on the Gashmu Bowl.

Nehemiah did not fall for any of the temptations, however. And progress on the wall continued until the work came to an end—after only 52 days. September 16 this year marks the 2,461 year anniversary of the completion of that wall.

It was a remarkable feat. A full, heavyset wall constructed completely around Jerusalem, replete with fully functioning gates and towers, built by a ragtag group of volunteer laborers. Sure, some of it did exhibit a rushed nature of building—that much can be seen on the portion of wall that has been excavated. The wall needed to go up around the prone capital and temple as quickly as possible. But it was solid, it was fully functioning, it did the job, and it was a miracle.

“And it came to pass, when all our enemies heard thereof, that all the nations that were about us feared, and were much cast down in their own eyes; for they perceived that this work was wrought of our God.“ (Nehemiah 6:16).

Nearly one week after the completion of the wall (on the next holy day), the Jews gathered before the Water Gate (perhaps the very gate uncovered by Dr. Mazar, as described above) to hear Ezra the scribe read to them from the Book of the Law—the Torah. The Jews had lost most of the knowledge of the Holy Book by then. Ezra, who had specially prepared himself for the job of teaching it (Ezra 7:6, 10), opened the book—and the entire congregation, out of deep respect and humility, immediately stood up (Nehemiah 8:5). With tears of repentance mixed with great joy, the people began to relearn and rededicate themselves to the instruction given them through the Prophet Moses 1,000 years before.

The Deeds of Nehemiah

Nehemiah’s time in Jerusalem was over. Twelve years had passed, and he was required to return to Shushan and King Artaxerxes. However, he was able to return to Jerusalem later.

What he found at his return was deeply disturbing: One of the Jews’ enemies while they were building the wall, Tobiah, had manipulated his way into such a favorable position with a priest that he was given his own place to stay within the courts of the house of God! Not only that, the grandson of the high priest had married the daughter of Sanballat. Further, Nehemiah discovered Jews working and trading on the Sabbath and others had intermarried with various surrounding cultures, which God had forbidden. Such was the extent of this intermarriage, that the children in the city were unable to speak the Jewish tongue!

Nehemiah immediately ejected Tobiah from the temple and chased away the high priest’s grandson. He instructed the nobles to enforce Sabbath keeping and warned the foreign merchants against so much as camping outside the city walls on that holy day. Furthermore, he cursed those who had married those of the Ashdodites, Ammonites and Moabites, and removed them from the city. He reinstated the proper priestly offices and reestablished the proper worship of God.

Nehemiah was a powerful leader who would not be led along by the masses. His life’s work was one of going against the flow—no matter the persecution, be it from surrounding armies or even his own people—and standing up for God, without deviation. His story, as recorded in the Bible, stands as a testament to the work God was able to do through him.

But we no longer have just the biblical account. We have a growing archaeological account, giving evidence for a number of contemporary figures such as Artaxerxes, Darius i, Darius ii, Tattenai, Sanballat and Geshem. We also have accurate descriptions of regional politics, places and buildings—and we even have a portion of his wall.

It’s probably best to end this article with Nehemiah’s own words. He used this phrase several times in his book, including right at the very end, and it sums up the clear and defining goal behind his actions:

“Remember me, O my God, for good.”