Archaeologists have unveiled the discovery of a biblical judges-era fortress in Israel’s central Shephelah territory near Kibbutz Galon, overlooking the Guvrin Valley. The majority of the structure had long since been destroyed, but the foundational outline of it is well preserved and easily recognizable.

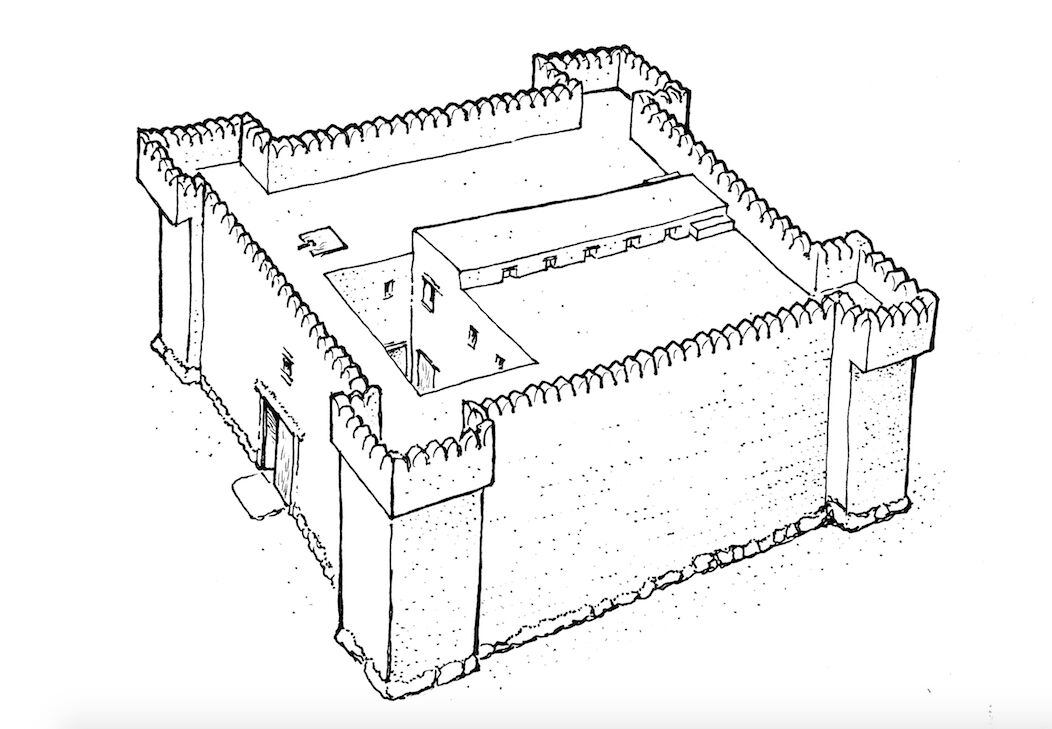

The Galon fortress measured 18 meters x 18 meters, and included four towers, one on each corner. The outpost fortress was divided in half, with a series of four chambers on both sides in the style of an Egyptian “governor house” and a paved courtyard in the middle, lined with columns. A massive, 3-ton threshold stone was discovered at the entrance to the building.

Numerous small finds were discovered in the building, including ritual items and hundreds of pottery vessels. The archaeologists date the construction of the fortress to around 1200 b.c.e. and, based on the nature of the building and the small finds, attribute it to the Egyptian-allied Canaanites.

But Was It From the Time of the Exodus?

In their press release, the excavators claim that the fortress dates to the time of the Israelite entry into Canaan—that at this time around 1200 b.c.e., the Israelites started to appear in the east and the Philistines in the west; the Canaanites, governed by Egypt during this period, were a waning power. They speculate that the reason for the construction of this 12th-century b.c.e. tower was to deal with this “new geopolitical situation.” Was this really the case?

Actually, there are two main theories when it comes to the date of the Exodus and the Israelites’ entry into Canaan. One matches these events up with the 15th century b.c.e.—this theory is based solely on information from the biblical account. The second, minimalist theory (favored by many archaeologists) takes a 13th to 12th century position, an Israelite arrival in Canaan some 200 years later. This theory is based on destruction material discovered and dated in cities throughout the region, a beginning change in material culture, and an admittedly selective reading of the Bible.

Yet none of the hard evidence thus far discovered negates the biblical 15th-century Exodus. In fact, it serves to support it—including the discovery of the Galon fortress.

A 15th-century biblical conquest of Canaan is easily pinpointed by several biblical passages. 1 Kings 6:1 says that Solomon’s temple was built 480 years after the Exodus. The construction of this is widely accepted as 967 b.c.e. (480 years prior gives us a 1447 b.c.e. Exodus, and a 1407 entry into the Promised Land, after 40 years of wandering). Likewise, the judge Jephthah (circa 1100 b.c.e.) sent a letter to the Ammonites, stating that the Israelites had, up to that point, been in the land for “three hundred years” (Judges 11:26). Furthermore, biblical genealogies (such as 1 Chronicles 6) are far too long for a 150-year judges period, but fit perfectly with a late 15th century arrival in the Promised Land, and an ensuing 350-year judges period.

Much of the debate hinges on destruction. Why were the Canaanites still in the land during the 12th century? Why was a Canaanite fortress up and running? What about the 13th-to-12th-century destruction layers? Why do certain Jews and Arabs today contain a genetic link to the Canaanites, when—according to Haaretz—the Bible claims that Joshua and his men completely extinguished them?

But the Bible doesn’t say that. In fact, the Bible takes pains to list numerous Canaanite cities that were left in the land, that Israel failed to conquer before and during the time of the judges (e.g. Judges 1). Actually, the Bible doesn’t describe the Israelites plowing through Canaan destroying cities (one of the archaeological “proofs” for a 13th-century Exodus—this discovered city-destruction does fit, though, with the later, 13th- to 12th-century bloody judges period). Instead, the Bible states that the Israelites would simply move into the existing Canaanite cities—“great and goodly cities, which thou didst not build, and houses full of all good things, which thou didst not fill …” (Deuteronomy 6:10-11). The Bible only mentions three specific cities as being destroyed by the Israelites during their entry into the Promised Land—and certain evidence has been found of this destruction, matching with an earlier Exodus date. Instead of major city-sieges, the Bible describes numerous staged land battles with the Canaanites.

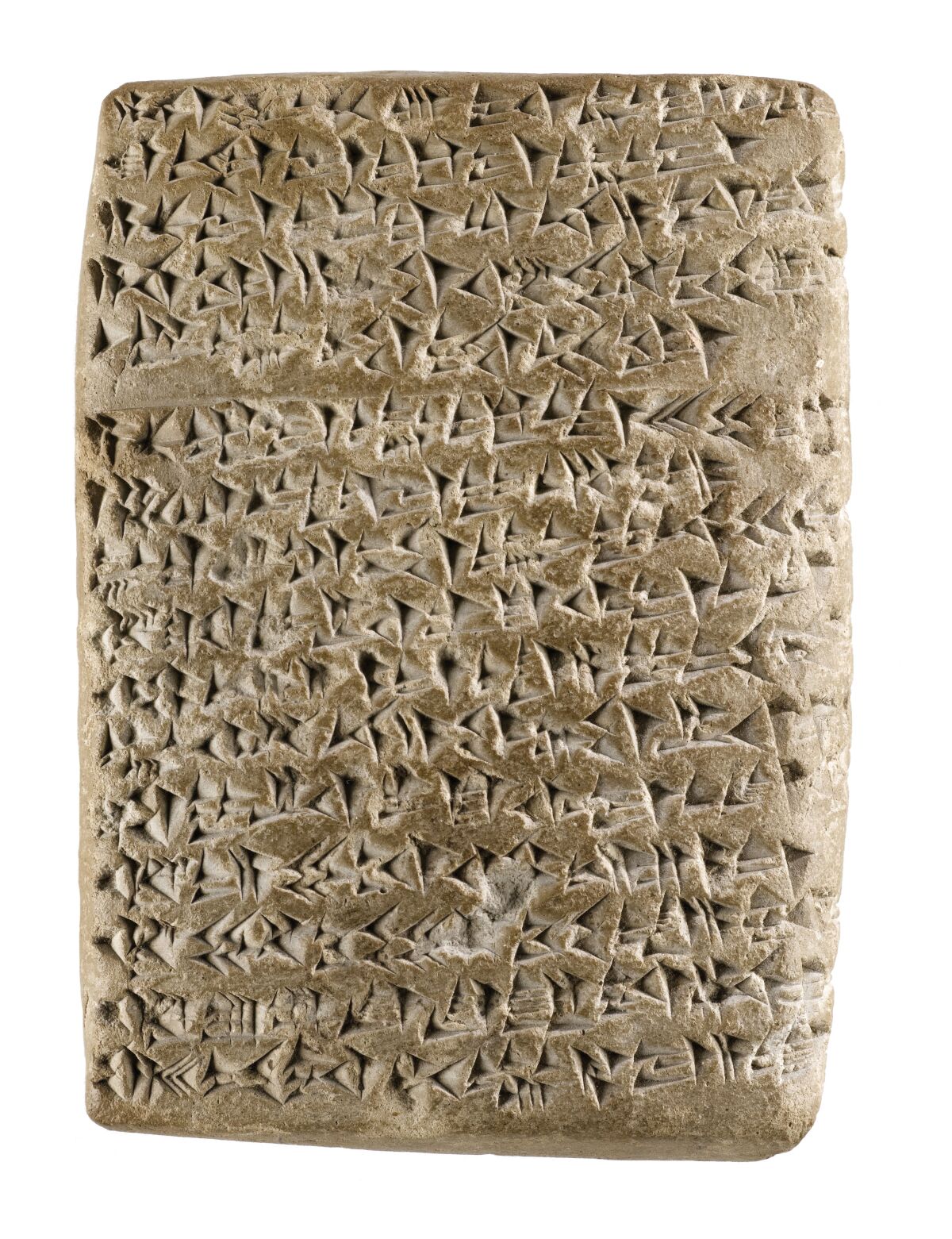

And this wholesale Israelite advance through the land and conquest of territory, from the end of the 15th century to the beginning of the 14th century, is borne out by archaeology. The 14th-century b.c.e. Amarna letters, written by desperate Canaanite mayor-kings to the Egyptian pharaoh, frantically and repeatedly state that “all the lands of the pharaoh” are “lost” to an invading group of nomads they called the Habiru. Amarna letter EA286 states:

May the king [Egypt’s pharaoh] provide for his land! All the lands of the king, my lord, have deserted …. Lost are all the mayors; there is not a mayor remaining to the king, my lord. The king has no lands. That Habiru has plundered all the lands of the king. If there are archers this year, the lands of the king, my lord, will remain …. (From Abdi-Heba, Canaanite Mayor of Jerusalem)

And inscriptions such as the Merneptah Stele (1207 b.c.e.) and Berlin Pedestal (date uncertain, between 15th and 13th centuries b.c.e.), both of which mention Israel by name, prove that the nation of Israel was already a well-established nation by at least the 13th century b.c.e.

So What of the Galon Fortress?

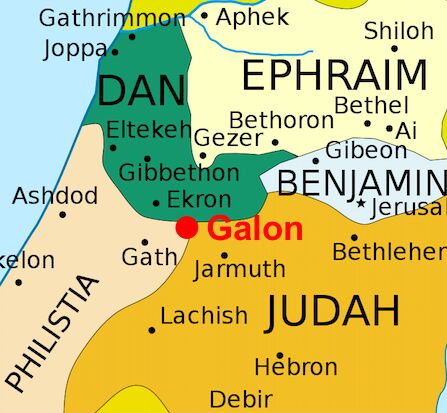

Unfortunately, we do not yet have sufficient information to identify the Galon fortress with a known biblical location. Based on its geographical position, the fortress would have been in the allocated territory of either the tribe of Dan or Judah (somewhere along the border). As such, it could constitute a Canaanite-Amorite territorial stronghold that the tribe of Dan allowed to stand (Judges 1:34-36), or perhaps, part of the Canaanite territory alongside the land of the Philistines that the Judahites failed to overthrow (verse 19).

What we do know is that the Canaanites remained a force to be reckoned with, right through the time of the judges. One of the great Israelite oppressions during this period was at the hand of a powerful Canaanite king, Jabin (Judges 4-5). And God stated that He would use the Canaanites remaining in the land as punishment, “to teach [Israel] war” (Judges 3:2).

Sometime during the 12th century, the Galon fortress was abandoned. The excavators speculate that this could have been the result of severe pressure on the Canaanites from immigrating Philistines into nearby cities, such as Gath. This was also around the time of the biblical Samson, where the Bible notes that the Philistines began to dominate the coastal region. As such, rather than the Israelites driving out the Canaanites from this territory—it may have been the Philistines who ultimately did so.

The Galon fortress was excavated by a special team, guided by the Israel Antiquities Authority—students from a school in Beer-Sheva, various volunteers, and youths participating in a pre-military preparatory program. This program is part of a summer induction to help the youths realize the history they are fighting for.

Perhaps with the excavation of this city, there is somewhat more of a military lesson for these pre-conscription teenagers—the consequences of not fully taking care of a problem, of tolerating belligerent enemy elements in the land, in spite of God’s instructions.