Science museums in general are not renowned for any interest in biblical texts (perhaps “hostility” toward them would be a better characterization). Yet for those who know where to look, many of them are a real treasure trove of biblical artifacts. The British Museum in London, England—one of the greatest museums on Earth—is certainly no exception.

I recently visited the museum with a youth camp group. Before our expedition to London, we spent some time learning about the key artifacts of biblical significance displayed in the museum. While there are many, we short-listed some of the very best. Be it mentioning specific biblical names and/or events, these impressive artifacts are a testament to the veracity of the Bible. Below is a short description of each artifact with biblical relevance that is housed at the British Museum, ordered according to their parallel chronology in the Bible story. The campers took a similar printout of this list with them around the museum—hopefully this article is helpful, especially to any of our readers who may visit the British Museum in the future. And even for those who may not have the chance to visit, this article will at least help animate the life and times of the Bible, illustrating its pages and directly proving its veracity.

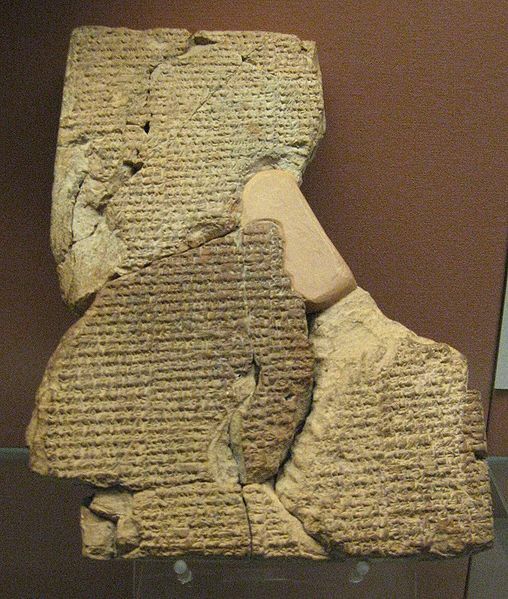

The Epic of Creation

This is an Assyrian artifact dating to around 650 b.c.e. The story is known to be a copy of an earlier version dating to around 2000 b.c.e.—making it perhaps the earliest creation story discovered through archaeology. The Epic of Creation discusses the Assyrian version of the beginning of the world, and due to its early original composition, it is not surprising that its details parallel many of those in the Bible. The Epic:

- Mentions the creation of world (Genesis 1-2)

- Describes a state of chaos and many waters (Genesis 1:2)

- References the birth of a son, revered as “avenger” and “heroic,” “We, whom he succored” (a possible parallel to Cain; Genesis 4:1)

- Mentions the presence of monster snakes (Genesis 3)

- References the “Sabbath” (Genesis 2:1-3).

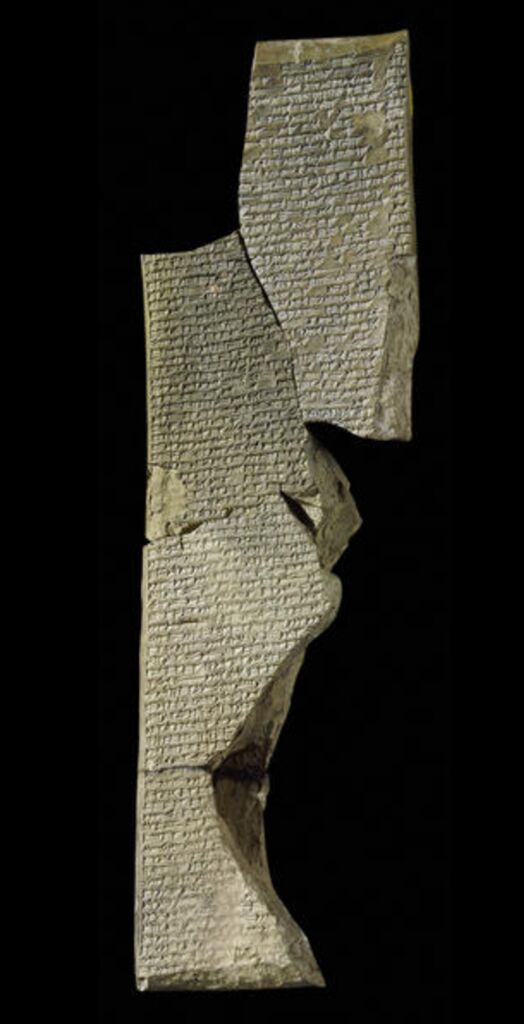

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Another Assyrian artifact dating to around 650 b.c.e.—again, a copy of an earlier (fragmentary) story believed to date as far back as 2200 b.c.e. The Epic of Gilgamesh discusses the Sumerian version of the great Flood. The Epic describes:

- A great Flood (Genesis 6-8)

- A boat built for the hero, his family, and all animals (Genesis 7:1-2)

- The Flood as punishment for human wickedness (Genesis 6)

- The ark resting on a mountain after the waters recede (Genesis 8:4)

- The hero releasing dove and raven species to check for dry land (Genesis 8:6-12)

- The hero offering sacrifices (Genesis 8:20).

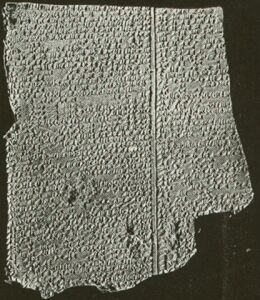

The Epic of Atra-Hasis

This is a Babylonian artifact, dating to around 1650 b.c.e., describing the Babylonian version of the great Flood. It describes:

- A great Flood (Genesis 6-8)

- A hero instructed to build a boat for him and the animals to survive (Genesis 7:1-2)

- Specifically that animals entered two-by-two (Genesis 7:2-9).

Amarna Letters

These letters are from Canaanite rulers, addressed to the Pharaoh of Egypt. They date to the time of the Israelites entering and conquering the Promised Land (throughout the 14th century b.c.e.). They are desperate pleas for Egypt’s help against what the Canaanites see as homeless peoples invading and conquering the entire land of Canaan. In a parallel theme to the Book of Joshua, the Amarna Letters:

- Name the fierce “nomadic” attackers as Habiru (or Hapiru, a very similar-sounding term to Hebrew)

- Mention the names of numerous biblical Canaanite cities

- Describe the widespread conquest of Canaan and defeat of cities that the Bible states were taken by the Israelites.

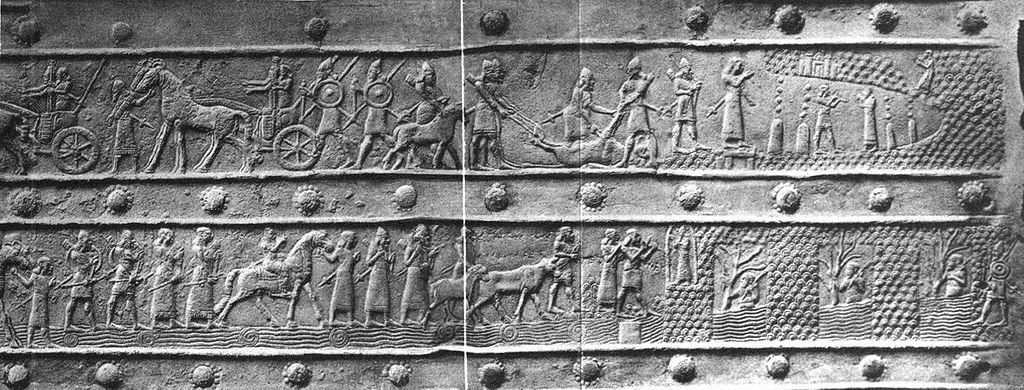

Balawat Gate

This display dates to around 850 b.c.e. The main gate display at the museum is a replica, while the original bronze gate bands and depictions are displayed around the room. These gates belonged to the Assyrian city of Balawat, located near to Nineveh. The gates and associated carvings:

- Are an example of the type of gates the prophet Jonah may have walked through, in preaching to nearby Nineveh (Jonah 3:3-4; 4:5)

- Provide some insight as to why God sent Jonah; they depict and glorify horrific torture practices, well-known also from Assyrian documents (Jonah 3:8)

- Likewise provide some insight as to why Jonah was so terrified to preach against Nineveh (Jonah 1:3)

- Help illustrate the size and might of the general Assyrian Empire (Jonah 3:3; 4:11).

Part of the bronze gilding of the gates of Shalmaneser III from his palace at Balawat Public Domain

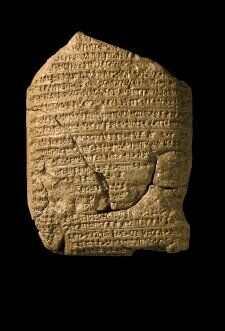

Kurkh Monolith

An Assyrian monument dating to around 850 b.c.e., documenting Shalmaneser iii’s victories against an alliance of kings. The Kurkh Monolith:

- Confirms the existence of King “Ahab the Israelite” (1 Kings 16-22)

- Also mentions the biblical king of Syria (Hadadezer—not named in the Bible, however referenced in 1 Kings 22:3, 31; 2 Kings 5; 6:8-23)

- Provides evidence for peaceable relations and military cooperation between Israel and Syria (1 Kings 20:31-34; 22:1)

- Demonstrates the power of the kingdom of Israel—Ahab sent 10,000 Israelite troops to the Battle of Qarqar—this is an extremely large force for a battle like this in ancient times.

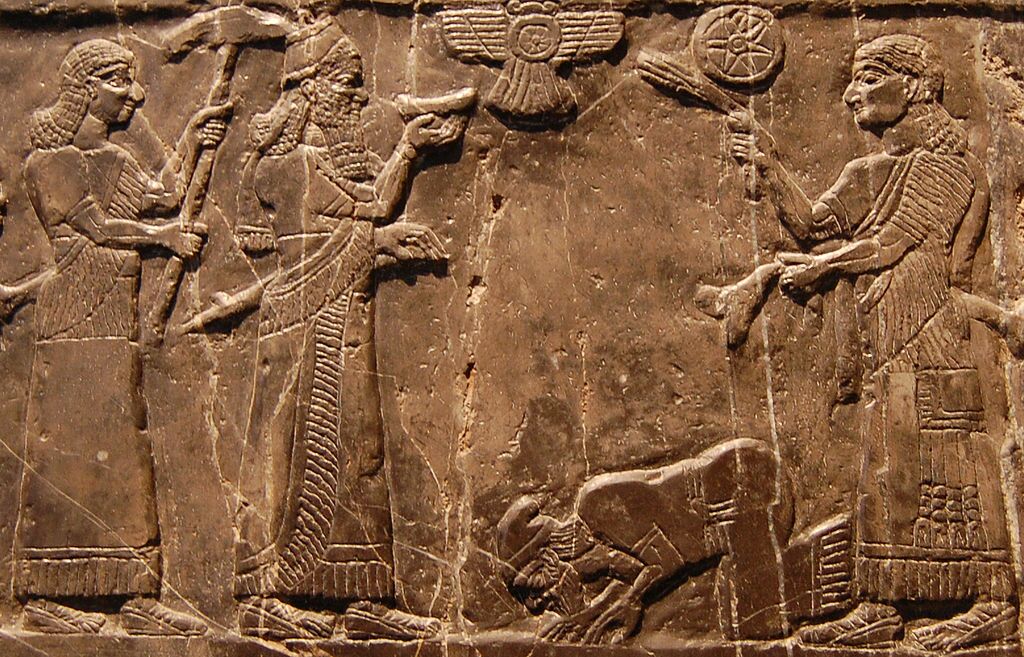

Black Obelisk

This is another victory stone of Assyrian King Shalmaneser iii. It dates to the same time as the Kurkh Monolith. The Black Obelisk:

- Names the Israelite King Jehu (2 Kings 9-10)

- Documents tribute paid by the Israelites under Jehu (perhaps during his later, rebellious years)

- Contains a depiction of a kneeling man at the front of those delivering tribute—a very possible depiction of Jehu. If it is him, it would be the only known depiction of an Israelite king

- Also names the king and “father” of the northern kingdom of Israel, Omri (1 Kings 16).

Possible depiction of Jehu King of Israel giving tribute to King Shalmaneser III Steven G. Johnson | CC

Tiglath Pileser III Inscription

This Assyrian inscription dates to around 730 b.c.e. It is a plaster tablet from the Assyrian palace at Nimrud. The inscription:

- Belongs to the biblical king of Assyria, Tiglath Pileser (2 Kings 15:29)

- Mentions King Ahaz of Judah (2 Kings 16:7, called by the longer form of his name, “Jehoahaz,” on the inscription)

- States that Assyria received tribute of silver and gold from Ahaz (a fact directly confirmed in 2 Kings 16:8).

LMLK Seals

These are Judean pottery handle stamps, of which thousands have been discovered. They belong to the reign of Judah’s King Hezekiah. While their purpose is not totally understood, the lmlk seals:

- Bear the text “lmlk,” meaning “Belonging to the King”

- Also each bear the name of one of four cities (three of which are known from the Bible—Hebron, Socoh and Ziph)

- Are believed to be some form of tax/ration vessels in preparation for Assyrian invasion (2 Kings 18-20).

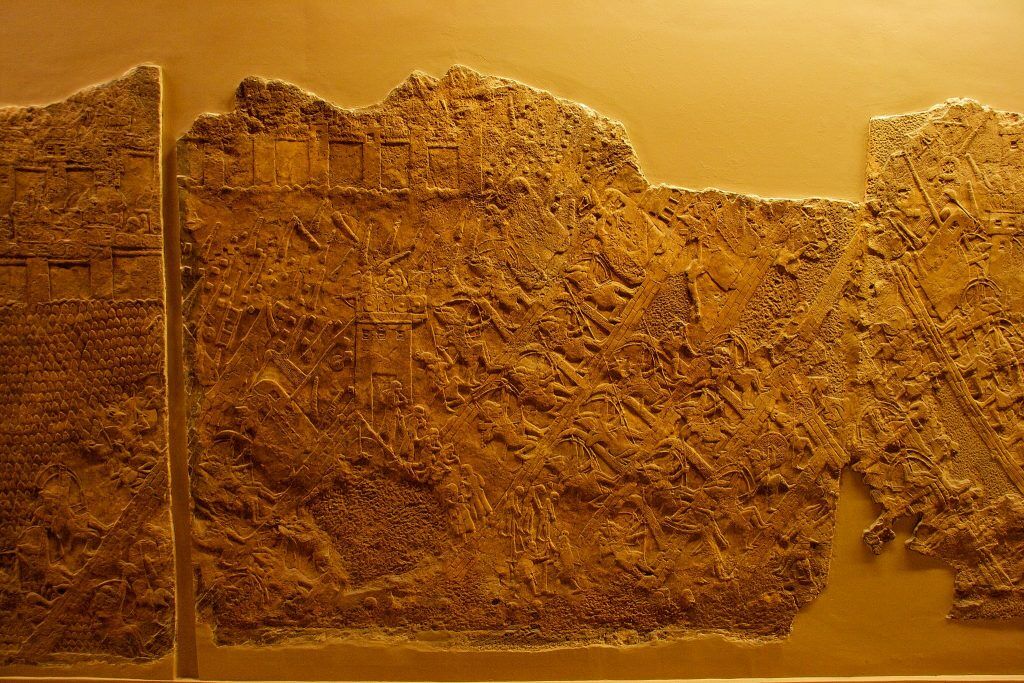

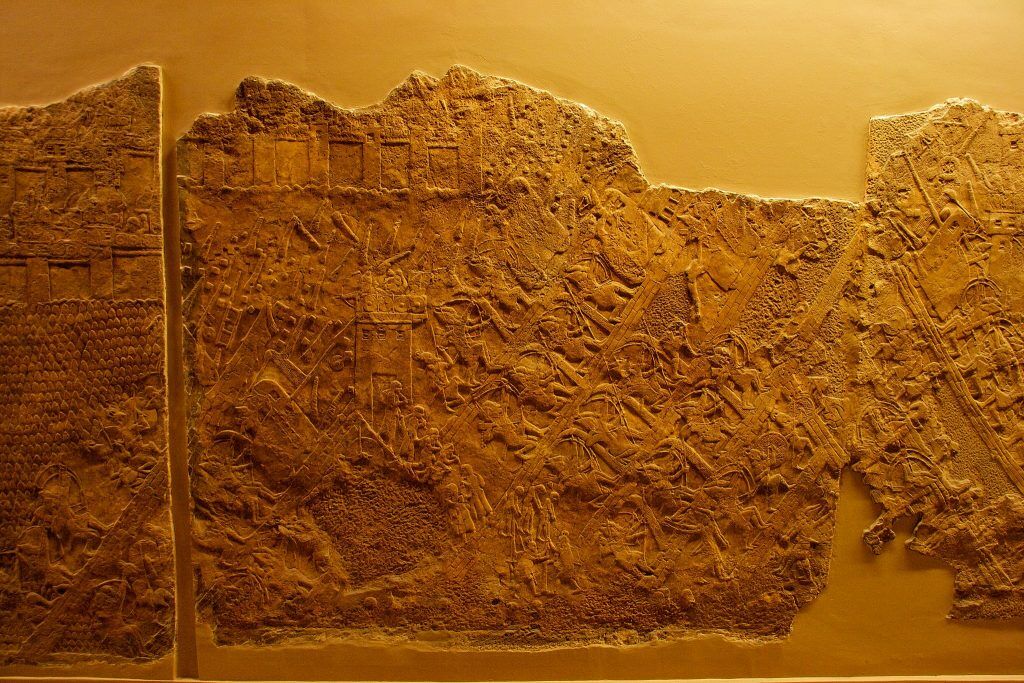

Lachish Reliefs

These wall carvings, or “reliefs,” are from King Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh. They date to around 700 b.c.e. and are part of a larger set of images portraying the power and might of the Assyrian king. There are other artifacts from the same battle located in the exhibit nearby. The Lachish reliefs:

- Confirm the existence of biblical King Sennacherib (Isaiah 36-37)

- Depict the Assyrians conquering Lachish (2 Kings 18:13-14; Isaiah 36:1-2; etc.)

- Help to prove that while Sennacherib was able to defeat Judah’s second-most important city, Lachish, he was not able to defeat Jerusalem (2 Kings 19—otherwise this would have been portrayed instead).

Winged-Bull Inscription

This inscription, also belonging to King Sennacherib, was framed between the legs of a large stone bull carving. The detailed text of the inscription:

- Proves the existence of King Hezekiah

- Documents his attempt to buy his way out of a siege (2 Kings 18:14-16)

- Confirms the exact amount of gold charged, as described in the Bible (30 talents) and also confirms the payment of silver (verse 14)

Taylor Prism

Another inscription belonging to King Sennacherib, dating to around 700 b.c.e. The Taylor Prism boasts of Sennacherib’s victories. The prism:

- Also references King Hezekiah

- Confirms Sennacherib setting up his forces around Jerusalem (2 Kings 18:17)

- Conspicuously doesn’t mention any attacks on Jerusalem— merely boasts the act of “trapping” the Jews inside the city walls

- Confirms the fact that Sennacherib didn’t conquer Jerusalem—because he couldn’t! Yet that was not something that the vain king would admit. (2 Kings 19:35-37 describe the miraculous overnight death of 185,000 Assyrian soldiers at the hand of an angel.)

Shebna Inscription

The Shebna Inscription belongs to the lintel of a tomb found just outside Jerusalem’s walls. It dates to around 700 b.c.e. The inscription:

- Is believed to belong to Shebna the treasurer of Isaiah 22 (the name is mostly cut out and damaged, however)

- Pronounces a curse on whomever opens the tomb, ringing similar to the curse declared against Shebna and his tomb in Isaiah 22:15-19. Added significance is given by the fact that the name is gouged out

- Note a seal stamp displayed at the museum near this lintel with the text “Shebna, son of Ahab”—this is possibly the same Shebna.

Babylonian Chronicle

This is a Babylonian document belonging to King Nebuchadnezzar. It dates to the start of the sixth century b.c.e. The Babylonian Chronicle:

- Proves the biblical King Nebuchadnezzar

- Describes his conquests of “Hatti-land” (the combined territory of Syria and Israel)

- Describes the “City of Judah”

- Mentions that Nebuchadnezzar appointed his own king over Judah—confirming the Bible’s account of Nebuchadnezzar appointing the last Judean king, Zedekiah (2 Chronicles 36:10).

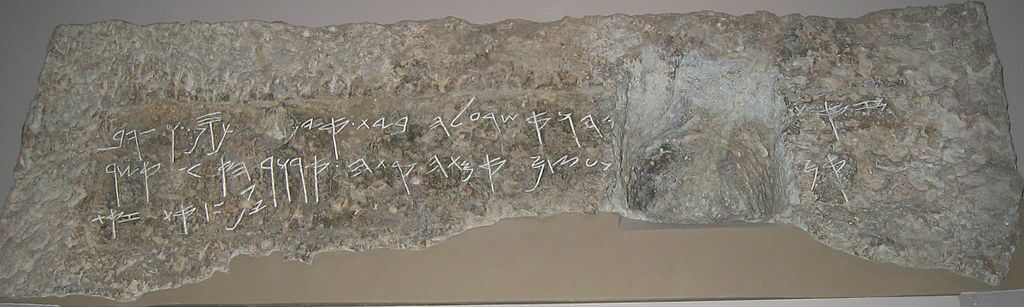

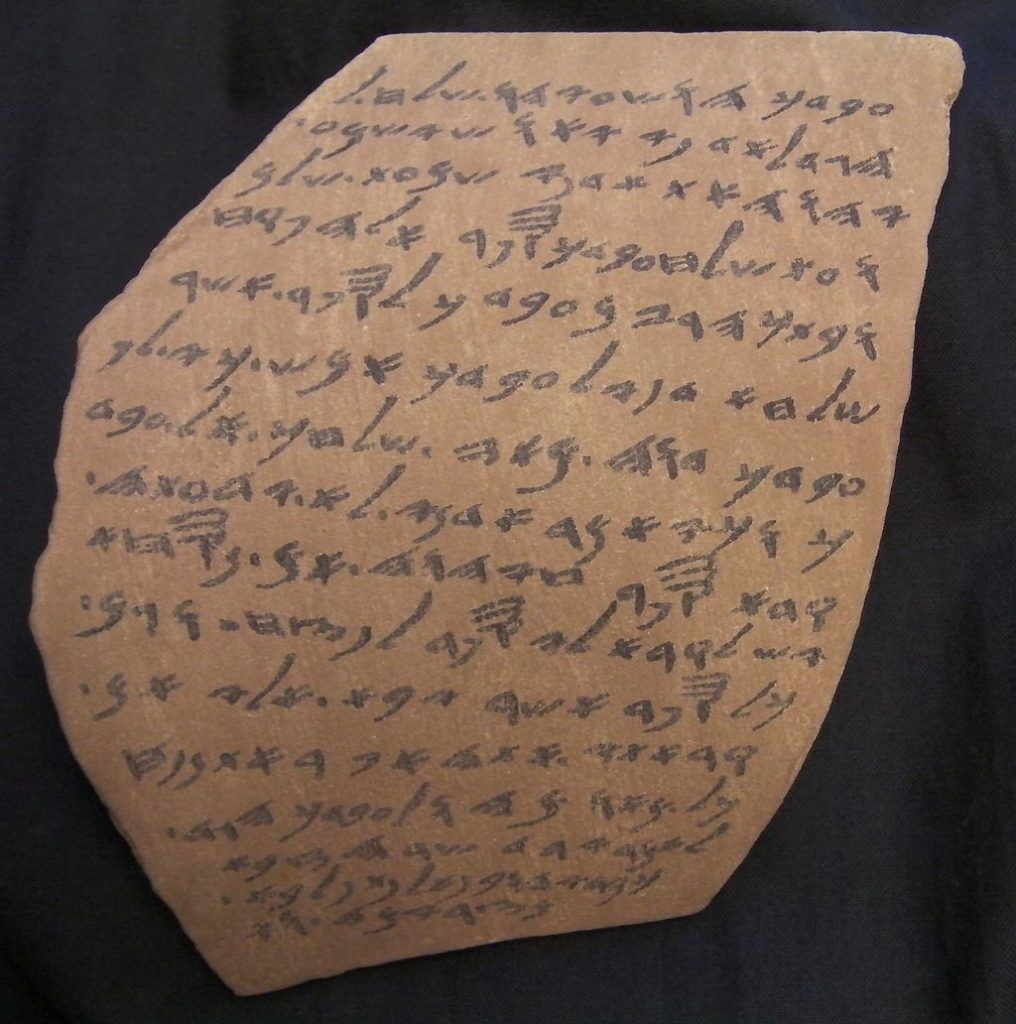

Lachish Letters

The Lachish Letters date to just before the fall of Judah—around 587 b.c.e. They are Hebrew ink inscriptions on pottery, giving a unique insight into the final moments of Judah before the fall to the Babylonians. The Lachish Letters:

- Describe the story of two biblical cities, Azekah and Lachish (Jeremiah 34:7)

- One of the Lachish letters discovered mentions an officer desperately waiting to see fire signals from Lachish because they cannot be seen from Azekah. This meant that Azekah must have been captured already by the invading Babylonians, and the nervous officer was waiting to see if the same was true at Lachish.

Nebo-sarsechim Tablet

This little tablet also belonged to King Nebuchadnezzar. It discusses one of his leading generals. The Nebo-sarsechim Tablet:

- Confirms the existence of a general described in Jeremiah 39:3 as being present at the fall of Jerusalem

- Verse 3 lists a number of names of Babylonian chiefs. However, the Jewish Publication Society’s translation is poor. The names “Samgar-nebo, Sarsechim, Rab-saris” are better translated “Samgar, Nebo-sarsechim the Rabsaris”

- “Rabsaris” was the position that Nebo-sarsechim held.

Nabonidus Cylinder

This small cylinder dates to around 550 b.c.e. It belongs to the last king of the Babylonian Empire, Nabonidus. King Nabonidus was held as proof against the veracity of the biblical account, because the Bible stated that a man named Belshazzar was the last king of Babylon (Daniel 5). However, the discovery of the Nabonidus Cylinder revealed that.

- King Nabonidus had a firstborn son named Belshazzar

- This son therefore became de-facto king of the capital city Babylon while his father spent much time away in the far reaches of his kingdom

- The existence of Belshazzar, in a second-place position of government, makes sense against the biblical account—Belshazzar gifted the prophet Daniel a position third in rank—that was the highest honor that the king could have given him.

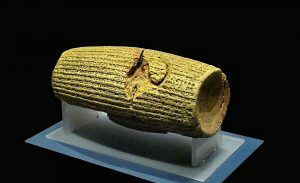

Cyrus Cylinder

The Cyrus Cylinder is one of the most famous pieces in the British Museum. Dating to 536 b.c.e., this inscription belonged to the Persian King Cyrus the Great. It is known as one of the earliest charters of human rights and showed the great and unusual benevolence of King Cyrus toward his conquered peoples. The Cyrus Cylinder, specifically directed to the captured Babylonians:

- Is one of the many archaeological proofs of King Cyrus

- Decrees that the people are allowed to continue their lives as normal under the Persian Empire, continuing to worship their gods, build their temples, etc.

- Essentially is a version of what is documented in Ezra 1:1-3, where King Cyrus allows the Jews freedom under his rule to return to their homeland, rebuild the temple, and worship their God.

- This benevolence toward conquered peoples was highly unusual in the ancient world, and thus this inscription confirms the biblical precedent attributed to the King Cyrus.

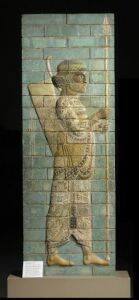

Persepolis Plaster Cast

This Persian plaster cast is believed to portray King Xerxes with his scepter. As such, the cast:

- Demonstrates what the husband of the biblical Esther looked like (Xerxes is believed to be the most likely candidate for the Persian King Ahasuerus in the Hebrew Bible)

- Regarding the scepter portrayed on the cast: Unless the king extended this, anyone who entered his inner court without invitation would be put to death (Esther 4:10-11). Queen Esther, urgent to talk to the king, entered his inner court without prior invitation. Ahasuerus extended this scepter toward her, which Esther came forward and touched (Esther 5:2).

Susa Glazed Brick Panel

This beautiful brick paneling belonged to the eastern gate of the palace at Persia’s capital city. Dating to around 500 b.c.e., the glazed brick panel:

- Belonged to the palace Susa, where the biblical account of Esther took place (“Shushan” in the Hebrew Bible; Esther 1:2)

- Would have been part of the same palace structure during the time of Queen Esther

- Would have been a familiar section of wall to Esther’s older cousin and guardian, Mordecai. Mordecai was known to be stationed “in the king’s gate”—perhaps that station was right next this very image! (Esther 2:21)

These are some of the more special and unique biblical artifacts that the British Museum displays. There are many, many others that can be pointed out, to varying degrees of biblical “significance.” There is something really special about seeing these artifacts. Real, tangible pieces that provide the “illustrations” to the biblical text. Pieces that prove the veracity of the Bible, real pieces that you could just reach out and touch (although please don’t literally touch the artifacts—I got told off myself for getting too close to one of them!).

On our site, we have been going through the various biblical stories that have been proved through biblical archaeology. The accurate biblical descriptions of civilization after civilization. Of city after city. Of personality after personality—multiple dozens of which have been validated by archaeology. Of individual artifact after artifact, of general story after story. While archaeology is a relatively “new” profession, it is simply remarkable just how much has been found thus far validating the biblical record.

Take the kings of Israel and Judah. Not that long ago, they were only really known from biblical sources—certainly not from artifacts. Now, archaeology has confirmed the existence of kings David, Omri, Ahab, Jehu, Joash, Jeroboam, Uzziah, Menahem, Pekah, Ahaz, Hoshea, Hezekiah, Manasseh and Jeconiah. These have all been named through scientific discoveries—and many of them, through multiple archaeological references. Time will only reveal more names. The British Museum houses evidence of five of those kings, plus the names of many more biblical figures.

The Bible is being proven to not just be a book of cute stories and a few historical names. The widening body of evidence for it is irrefutable. And the British Museum has become just one of many (albeit unintentional!) preservers of the incredible scriptural past.

You’ve read the biblical stories. Now, if you have the chance, go and see them.