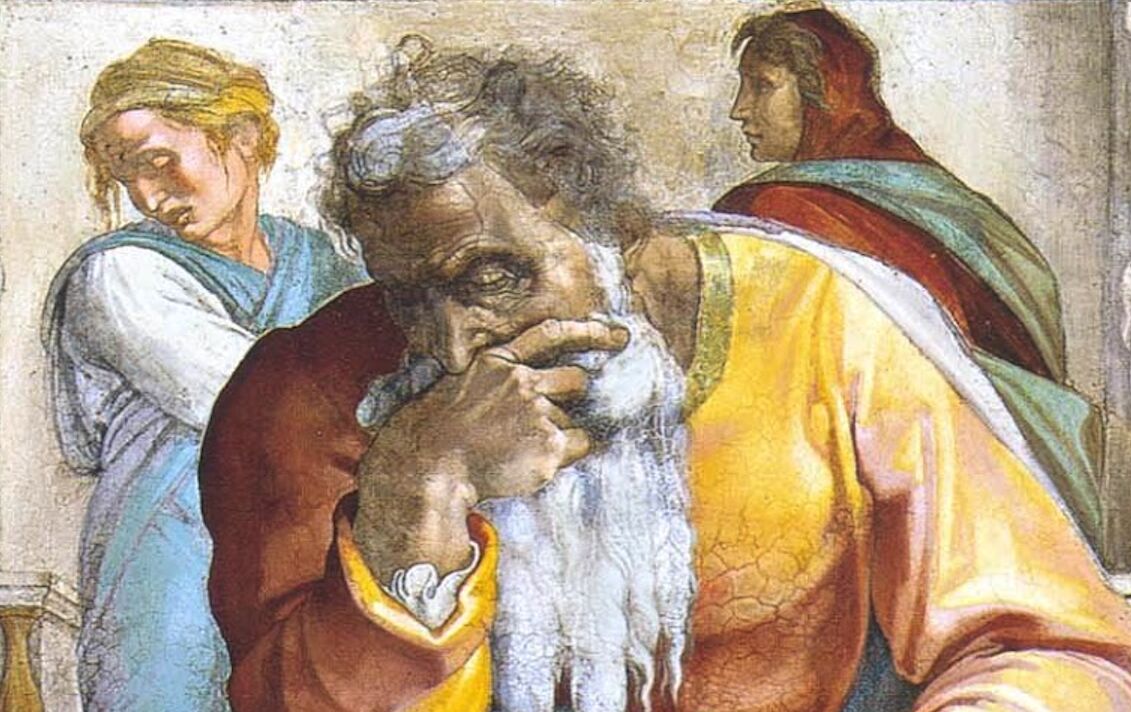

“Belonging to Gedaliah, son of Pashur,” read the tiny inscription embossed on the ancient clay seal. As the archaeologists turned it over, they could clearly make out the preserved fingerprints on the seal, surely made by this very man 2,600 years ago as he steadied the clay bulla to stamp on it his seal impression. The fine grain of the papyrus document that the clay seal was attached to had been etched into its back, along with the crisscrossing of thread that bound the important document together. At a size of only 13mm, the clay seal, blackened and hardened by an ancient fire, had nearly been missed by the archaeologists. Nonetheless in 2008 it was carefully delivered from the ground, stunningly bringing to life a real individual that had to that point only been known from pages of the Bible. This individual has left but a short record for us: a clay seal, three fingerprints, and a grim record as archenemy to the prophet Jeremiah.

But this wasn’t the only one of Jeremiah’s enemies to surface from the dust of history. A similar clay seal had been found three years before, belonging to a fellow prince of Gedaliah’s and fierce opponent of the prophet: Jehucal, son of Shelemiah. Truth be told, Jeremiah was a widely hated man of his day. His predictions of the fall of Jerusalem and pleas for peaceful surrender to Babylon caused Judah’s ruling classes to loathe him. Yet the test of time has vindicated the “Weeping Prophet” and condemned his enemies. Today, Jeremiah is revered as one of the greatest men of the Bible, while his enemies are virtually forgotten.

With the advent of modern archaeology, we now not only have the biblical record of Jeremiah’s life—new discoveries are continuing to shine light on the real people he interacted with, and the places that he travelled. Thus far, at least 16 different biblical figures who lived contemporaneously with Jeremiah have been validated by archaeology. Not to mention Jeremiah’s accurate regional assessments and diplomatic descriptions that also match the historical record. The book of Jeremiah isn’t a fringe pseudo-history with an odd name that happens to correspond to actual events.

Science is uncovering not only mere snippets of the Bible, but entire stories. As with our last article on King Hezekiah, we now examine in-depth the true story of the Prophet Jeremiah.

Jeremiah’s Beginnings

According to the biblical record, Jeremiah must have been born around 645 b.c.e. He was a young man when he was called by God to begin prophesying.

Then the word of the Lord came to me, saying: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you; Before you were born I sanctified you; I ordained you a prophet to the nations.” Then said I: “Ah, Lord God! Behold, I cannot speak, for I am a youth.” But the Lord said to me: “Do not say, ‘I am a youth,’ for you shall go to all to whom I send you, and whatever I command you, you shall speak. Do not be afraid of their faces, for I am with you to deliver you,” says the Lord. (Jeremiah 1:4-8, New King James Version)

Judah, at that time, was in the middle of King Josiah’s reign. Actually, Josiah was a righteous king, who had accomplished a great deal in rooting out idolatry from the land of Israel. Of this king, God had said, “And like unto him was there no king before him, that turned to the LORD with all his heart, and with all his soul …” (2 Kings 23:25). During Josiah’s reign, the Book of the Law was rediscovered by the High Priest Hilkiah (a man confirmed archaeologically, whose name has been found on the seal of his son, Azariah). Josiah strictly began to enforce observance of this book (probably Deuteronomy, if not the entire Torah), in order to postpone Judah’s coming punishment. So why, then, did Jeremiah begin prophesying against Judah during the reign of this righteous man? Truth be told, Judah had been doomed by the actions of those who came before Josiah.

Notwithstanding the LORD turned not from the fierceness of His great wrath, wherewith His anger was kindled against Judah, because of all the provocations wherewith Manasseh had provoked Him. (verse 26)

Manasseh, Josiah’s grandfather, was about the most evil of Judah’s kings. He had a record of idolatry, child sacrifice, sorcery and communion with demons. He “filled Jerusalem from one end to another” with innocent blood. And so while righteous king Josiah would be spared witnessing the downfall of his nation, it was nevertheless inevitable. Hence Jeremiah’s unpopular preaching.

Jeremiah thus began delivering his message in the streets of Jerusalem. If he didn’t get much support from the people, at least he would have had it from King Josiah. But King Josiah wouldn’t be around much longer.

Josiah Dies, Judah’s Fall Begins

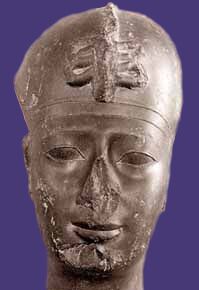

The geopolitical scene at the end of the 7th century b.c.e. was a rocky one. The Assyrian Empire was losing power. The emerging Babylonian Empire was rapidly growing in might, and had forced the Assyrians back from their capital city to Harran. Under the command of Nabopolassar, the Babylonians were about to deliver another blow to the Assyrians. It was down to the Egyptians to arrive and save Assyria from a dangerously expansive Babylonian Empire. In order to join the battle, Pharaoh Necho had to take his troops through the Kingdom of Judah and what was now the defeated and evicted wasteland of the northern Kingdom of Israel. King Josiah, though, would have none of it. He gathered his troops at Megiddo, and prepared to mount a stand against Necho. The pharaoh pleaded for Josiah’s sake to simply let him through; otherwise, Judah’s armies would face certain destruction. Yet Josiah stubbornly took his men to the vital passage route of the Valley of Megiddo, and battle ensued. King Josiah actually went to this battle disguised, so as to not be pinpointed by the attackers as king (2 Chronicles 35:22). Yet there Josiah met his end.

In his days Pharaoh-necoh king of Egypt went up against the king of Assyria to the river Euphrates; and king Josiah went against him; and he slew him at Megiddo, when he had seen him. (2 Kings 23:29)

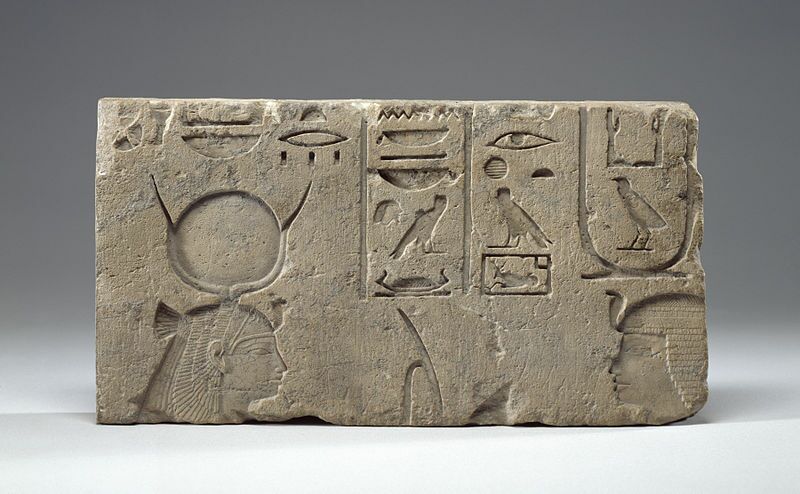

Pharaoh Necho (as his name is spelled in 2 Chronicles in the King James Version) is not just a biblical character. He has been well attested to in inscriptions. Precisely known as Necho ii, he is well known for directing this Egyptian army up towards Harran to join with the Assyrians in attempting to ward off the Babylonian forces. The Pharaoh would be defeated by the Babylonians, though. Returning back through the Kingdom of Judah with his tail between his legs, he would console himself by exerting a powerful influence on the Kingdom of Judah. Pharaoh Necho discovered that Josiah’s son, Jehoahaz, had been made king in place of his father. Necho immediately uprooted him, levied a massive tax on Jerusalem, installed Josiah’s other son Eliakim as king, renamed him Jehoiakim, and took the captive Jehoahaz back to Egypt (2 Chronicles 36:1-4).

Josiah’s defeat and death had been a tragic moment for Judah and, specifically, the prophet Jeremiah. In fact, the book of Lamentations was written as a result of his death (e.g. 2 Chronicles 35:25). Josiah was the last righteous king of Judah. Jeremiah realized that with this upright leader gone, the horrifying prophecies of Judah’s downfall would be postponed no longer. The fury of this returning, defeated Pharaoh Necho was only the very outer edge of the coming storm.

Jeremiah vs. Jehoiakim

The prophet Jeremiah continued prophesying the unpopular message of the sins and downfall of his nation. He admonished the people to look at Shiloh—the place of Israel’s tabernacle of old—to see how it was utterly destroyed for the wickedness of the people (Jeremiah 7, 26). Archaeological excavations at Tel Shiloh have confirmed that Shiloh was a wasteland during Jeremiah’s time. The city had been savaged by the Philistines 450 years earlier, leaving a one meter destruction layer for excavators to uncover. The city was resettled again somewhat during the 8th century b.c.e.; again, this resettlement was wiped out during the Assyrian conquests at the end of that century. Shiloh would have been a powerful indicator of what was coming.

Jeremiah’s sore predictions of Jerusalem turning into another “Shiloh” riled Jehoiakim’s princes. King Jehoiakim had only just begun his reign, after being instated by Necho. The princes clearly didn’t want any dissent, especially not this early on. They brought together a special counsel to consider killing Jeremiah. A man named Ahikam came to Jeremiah’s defence, and saved him (Jeremiah 26:9-24).

The same could not be said, though, for another prophet. Urijah prophesied against Judah, just as Jeremiah was doing. He, however, was a false prophet—he had not been commissioned by God, and did not have the same protection. Jehoiakim sent men to kill Urijah, who upon hearing of the threat, fled into Egypt. Jehoiakim was not to be stopped, and sent a team into Egypt that arrested Urijah and brought him all the way back before Jehoiakim, where he was slain.

Jeremiah was now shut away from publicly proclaiming the downfall of Jerusalem. That didn’t stop him, however. He dictated further prophecies to his scribe Baruch, who wrote them down on a scroll. Jeremiah then sent Baruch to read the scroll in the Temple. He took it specifically into the chamber of Gemariah, the son of Shaphan (Jeremiah 36:10).

The scribe Gemariah has actually been confirmed through archaeology. A royal clay seal was found during the 1982 excavations at the palace area of the City of David, The seal reads: “Belonging to Gemariah, son of Shaphan.” This man actually proved helpful to Jeremiah’s cause. He, along with other princes present, heard the words of the scroll, and immediately saw its significance. They motioned for Baruch to hide himself, and then they carried the message to King Jehoiakim. The king, of course, was furious. He snatched up the scroll as it was being read out to him, and despite the pleas of Gemariah and his fellows (verse 25), slashed the scroll and dropped it into his fireplace. Jeremiah immediately dictated a replacement scroll, proclaiming that Jehoiakim’s children would not continue on the throne of David. He further prophesied the ignominious death of the king.

Around this time Egypt, whose forces had been in the region of Syria, attempted to make a last stand with the Assyrians against the Babylonians at Carchemish. But this time, they would face a new Babylonian king: Nebuchadnezzar ii.

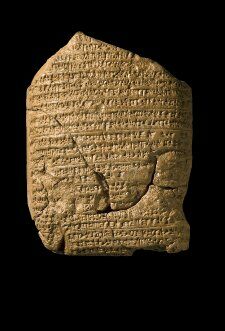

As the Bible records, the Egyptians were smashed at Carchemish (Jeremiah 46:2). And this isn’t only a battle mentioned briefly in the Bible. It is well known in secular history as being one of the truly great and decisive ancient battles. The Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle is a noteworthy inscription describing this crushing defeat that occurred in 605 b.c.e. The way was now clear for the Babylonians, under Nebuchadnezzar, to set their sights on Judah.

Babylonian Oppression Begins

King Nebuchadnezzar came up against Judah fairly early on, in order to subject Jehoiakim to Babylon. Initially, there doesn’t seem to have been any great invasion. This first Babylonian incursion must have been to ensure Judah’s submission to Babylon, instead of Egypt. This must have been deeply embarrassing for Jehoiakim, however—for he was now being forced to accept that Jeremiah’s prophecies of Babylonian incursion were coming true.

Jehoiakim’s subservience to Babylon lasted only three years, before he rebelled. Armies of Chaldeans, Syrians, Moabites and Ammonites set about plundering Judah. Nebuchadnezzar ultimately had Jehoiakim brought in chains to Babylon, along with various temple treasures and captives (2 Chronicles 36:5-8).

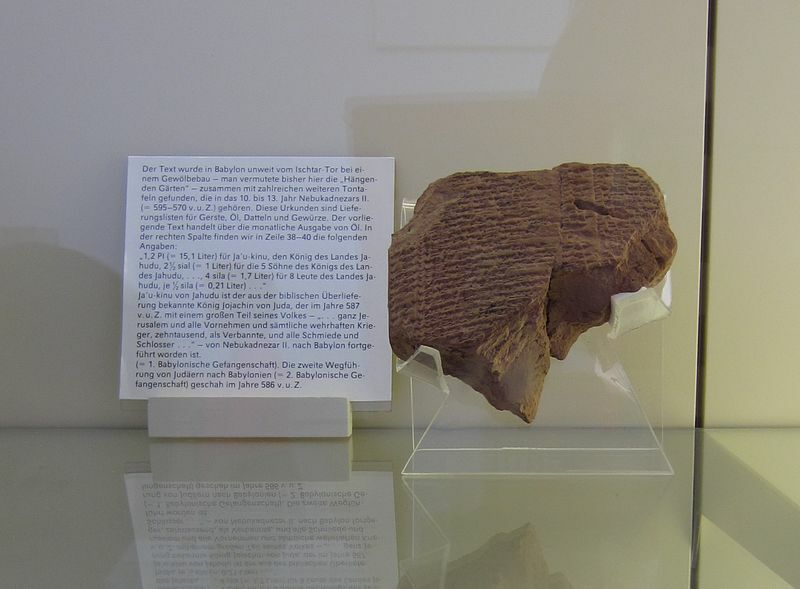

In place of Jehoiakim, Jeconiah his son reigned (also known as Coniah and Jehoiachin). This man had one of the shortest lengths of reign in Judah—just over three months. Even in this short period of time, he managed to establish a reputation as an “evil” king. Jeremiah prophesied that this man would fall into the hands of Nebuchadnezzar and that none of his seed would rule on the throne of Judah (Jeremiah 22). Subsequently, Nebuchadnezzar besieged Jerusalem a second time. Jeconiah, his servants and his mother emerged and gave themselves up to the king of Babylon. More treasures were looted from the temple and were carried back by the Babylonians, along with 10,000 captives. Among this captivity was the forefather of Mordecai and Esther (Esther 2:5-6). “None remained, save the poorest sort of the people of the land” (2 Kings 24:14). Jeconiah, while taken captive, was kept alive in Babylon. There has been some very interesting archaeological corroboration of what happened to this king.

In place of Jeconiah, Nebuchadnezzar made his uncle, Mattaniah, king—thus fulfilling Jeremiah’s prophecies that the families of Jehoiakim and Jeconiah would not continue on the throne. King Mattaniah is better remembered by another name given to him by the Babylonian king—Zedekiah. This king would have much interaction with Jeremiah over the course of his 11 year reign—and almost all of it bad.

Zedekiah and Jeremiah

Zedekiah was an evil and ineffective king. While afraid to personally deal with Jeremiah, he allowed his princes freedom to do with the prophet as they pleased. As such, Jeremiah was abused and imprisoned several times. The strain of prophesying such an unpopular message was taking its toll on Jeremiah, as revealed by an interesting insert after he had cursed a chief governor who had beaten him and put him in the stocks:

O LORD, Thou hast enticed me, and I was enticed, Thou hast overcome me, and hast prevailed; I am become a laughing-stock all the day, Every one mocketh me. For as often as I speak, I cry out, I cry: ‘Violence and spoil’; Because the word of the LORD is made A reproach unto me, and a derision, all the day. And if I say: ‘I will not make mention of Him, Nor speak any more in His name’, Then there is in my heart as it were a burning fire Shut up in my bones, And I weary myself to hold it in, But cannot. (Jeremiah 20:7-9)

Jeremiah was on the verge of giving up—yet God’s word was in him like a raging fire. He bravely continued to warn the Jews of their ways. A Babylonian invasion was inevitable. Especially so, because King Zedekiah had now rebelled against them.

King Zedekiah had the gall, even in his weak position, to defy King Nebuchadnezzar. The Babylonian king must have been incredulous. Again, he amassed forces to descend on Jerusalem. And again, Jeremiah continued to warn the population and ruling classes to repent and surrender to the Babylonians. If only they surrendered, their lives would be spared.

Babylon Conquers Judean Cities

The Babylonians now swept into Judah. We often think about this time period in terms of Jerusalem’s suffering and destruction—but it also included the destruction of the broader regional cities of Judah. Two other significant cities, named in the Book of Jeremiah, were set upon by the Babylonians.

[T]he king of Babylon’s army fought against Jerusalem, and against all the cities of Judah that were left, against Lachish and against Azekah; for these alone remained of the cities of Judah as fortified cities. (Jeremiah 34:7)

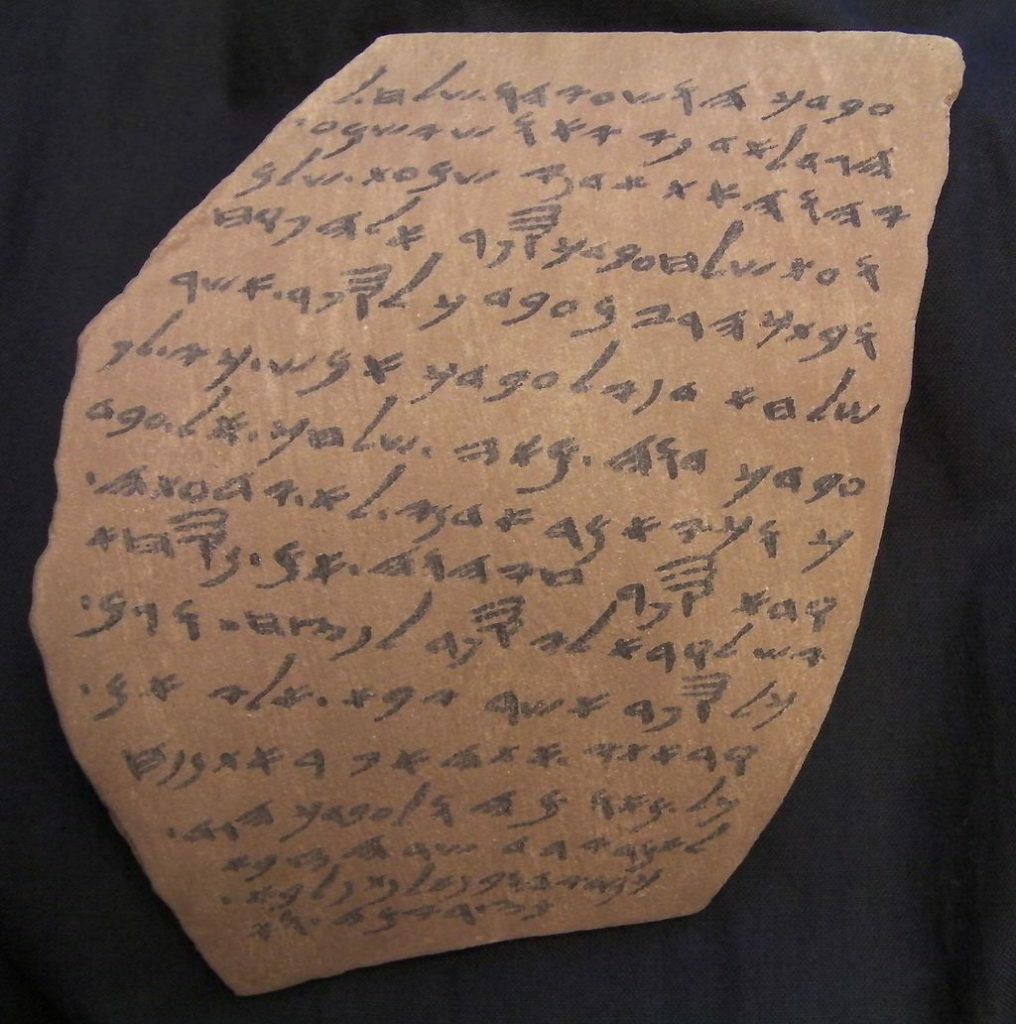

These cities, Lachish and Azekah, were in the process of falling, as an interesting artifact illustrates. The major cities of Judah communicated through massive fire signals. A fire signal meant that all was well. But now, as the “Lachish Letters” reveal, all was not well.

These “letters” are actually pottery fragments (or ostraca) written on by an officer located in a city outside Lachish to an officer inside Lachish. One of the letters, dating to the time of Babylonia’s incursion, reads:

And may (my lord) be apprised that we are watching for the fire signals of Lachish according to all the signs which my lord has given, because we cannot see Azekah.

The fact that the major city Azekah had failed to deliver a fire signal was a fearful sign that the city had already fallen to the Babylonians—and thus this outer city officer was worriedly watching to see if Lachish would deliver a fire signal. This text provides a remarkable, tense snapshot in time as the Babylonians steamrolled through Judah, destroying city after city.

Princes and Prison

In Jerusalem, meanwhile, King Zedekiah vacillated between asking Jeremiah to pray for the welfare of Judah, and throwing Jeremiah into prison. On one occasion, he sent Jehucal son of Shelemiah, along with Zephaniah, to ask Jeremiah to pray. Of course, this is what Jeremiah had constantly been doing. At this stage, it wasn’t him that was the one who needed to pray. And with the arrival of the Babylonians, it was certainly “convenient” that Zedekiah would now start asking favors from God.

This prince sent by Zedekiah, named Jehucal, has himself been attested to by archaeology (as briefly mentioned at the top of this article). A royal seal bearing the words “Belonging to Jehucal, son of Shelemiah” was found in excavations in 2005, around the royal palace at Jerusalem. While at this point Jehucal requested that Jeremiah pray for the city, he would again feature later on in an attempt to kill Jeremiah.

At this time the Babylonians, who had settled into a siege against Jerusalem, were interrupted by the Egyptians. Led by Pharaoh Apries (called Hophra by Jeremiah), this army attempted to come to Judah’s aid. The Babylonians uprooted themselves from Jerusalem and launched an attack on the Egyptians. Jeremiah told Jehucal and Zephaniah that the Egyptian army would return to Egypt, and the Babylonians would return to resume the siege against Jerusalem. He warned them not to be deceived by the fact that the Babylonians had temporarily departed.

While the Babylonian army had lifted the siege, Jeremiah took opportunity to go to the land of Benjamin, to visit his plot of land (most likely the same land that God commanded he buy while in prison, as a sign of the return of the Jews after captivity; Jeremiah 32). Jeremiah, however, was stopped upon his departure by Irijah, was accused of defecting to the Babylonians, and was beaten and thrown in prison by the princes. Perhaps this Irijah, who was a son of Shelemiah, was brother to the same Jehucal described above.

Judah’s princes, though, would have none of it. Jehucal, along with Gedaliah son of Pashur (described at the top of this article, his royal seal also having been found) and other princes pleaded that Jeremiah be put to death for weakening the resolve of the Jewish defenders (Jeremiah 38). Zedekiah turned the prophet over to their hands. Jehucal, Gedaliah, and their fellow princes marched to the court of the prison, forcibly took Jeremiah, and dragged him to the dungeon of Malchiah. This dungeon was filled up with a filthy mire, within which Jeremiah began to sink.

Ebed-melech, an Ethiopian eunuch, heard of what had been done to Jeremiah and rushed to the king requesting his release. Ebed-melech’s request was granted, and he went with thirty men to pull Jeremiah out of the miry dungeon. King Zedekiah again requested Jeremiah’s presence and counsel. Jeremiah advised surrender. Zedekiah, though, was worried—he feared that the Jews would mock him for turning the city over to the Babylonians. Jeremiah assured him they would not, and pleaded with the king:

Obey, I beg you, the voice of the Lord, in that which I speak to you: so it shall be well with you, and your soul shall live. (Jeremiah 38:20, hnv)

Jerusalem: Defeated

Despite Jeremiah’s pleas, Zedekiah would not relent. Finally, after one and a half years of siege, the Babylonians finally broke through into the city. Starvation had taken a heavy toll on the inhabitants. Zedekiah and the royal family attempted an escape through a secret passage under the cover of night—only to be caught by the Babylonians and carted off to King Nebuchadnezzar. There, the last thing Zedekiah witnessed was the slaughtering of his sons, before his own eyes were burned out—an ignominious end for a pathetic king.

There is archaeological attestation to a number of the biblical Babylonian princes present at this defeat of Jerusalem. One of these princes was named Nergalsharezer (Jeremiah 39:13). Archaeology has since revealed evidence of this prince as the son-in-law of King Nebuchadnezzar. He is known in the Akkadian language as Nergal-sar-usur (more commonly as Neriglissar). Another figure is Nebo-sarsekim, the Rabsaris (poorly translated into English in Jeremiah 39:3 as two separate names: “Sarsechim, Rabsaris”). Another is Nebuzaradan, the captain of the guard (verse 9). He is mentioned on Nebuchadnezzar ii’s prism as “Nabu-zer-iddin.”

The Babylonians treated Jeremiah favorably. King Nebuchadnezzar ii himself had heard of this man, and personally gave orders for the above-mentioned captain Nebuzaradan to treat him well. As such, Jeremiah was set free with a reward. The king of Babylon established Gedaliah as governor over the cities of Judah, within which only the destitute were allowed to stay. Judah was thoroughly crushed.

But this would not be the last the remaining Jews would see of the Babylonians.

Travels to Egypt, and Future Prophecies

A rogue Jew named Ishmael, who had some royal genealogy, gathered 10 men of dubious character and killed the Babylonian-appointed governor Gedaliah along with dozens of other Jews. Ishmael and his men then rounded up hordes of Jews and began herding them toward the land of the Ammonites, with whom Ishmael had allegiance. Ishmael and his men fled, however, when the captain Johanan and his forces arrived to free the captive Jews.

Johanan began to govern the beleaguered people. Fearing retribution from Babylon for the death of Gedaliah, the Jews began an “exodus” back into Egypt—against God’s warnings. Jeremiah prophesied that the Jews who would flee to Egypt would again face death at the hands of a Babylonian invasion. If they remained in Judah, they would be spared. Nonetheless, the Jews spitefully rejected God’s instructions (again!), and forcibly took Jeremiah with them to Egypt. At the city of Tahpanhes, Jeremiah repeated his proclamation that the Jews would suffer within Egypt at the hands of the Babylonians. True to form, archaeology has revealed a Babylonian invasion into Egypt that occurred around 568-567 b.c.e.—18 years after the fall of Judah.

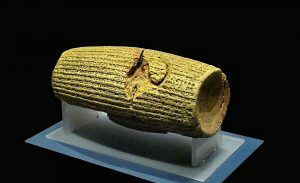

It is in Egypt that the biblical description of Jeremiah ends. Yet his various prophecies continued to come to pass, such as the prophesied return of the Jews to Judah after 70 years (Jeremiah 29: this was a letter he wrote to the Jewish captives as encouragement. The prophet Daniel took great hope from this message—Daniel 9). King Cyrus’s proclamation for a Jewish return allowed the fulfillment of this prophecy (Ezra 1:1-3). A similarly-worded proclamation from Cyrus to the defeated Babylonians, known as the Cyrus Cylinder, has been found, attesting to this unusual precedent of mercy given by King Cyrus to captive populations.

Many of Jeremiah’s prophecies also refer to the end-time—and have not yet been fulfilled. Such as that of a future “archaeological discovery”: that of the Tombs of the Kings. Jeremiah 8 describes that these tombs will be desecrated—ergo, they must first be found. Similarly, Jeremiah 3 even points to the Ark of the Covenant being found and “visited.” Further end-time prophecies describe a catastrophic time of trouble for Israel, just before the coming of the Messiah (e.g. Jeremiah 30). Jeremiah also prophesies the resurrection of king David to rule alongside the Messiah (Jeremiah 30:9).

But what of Jeremiah himself? There is no mention of his death anywhere in the Bible. Many conclude that he simply died in Egypt. What happened to him?

Jeremiah’s Continuing Story

Most people lose sight of the prophet Jeremiah after this point, and “close the book.” This is in large part connected to a failure to fully understand his commission from God. He was not just a “prophet of doom.” Right at the very beginning of his calling, God gave Jeremiah a two-part commission:

See, I have this day set thee over the nations and over the kingdoms, To [Number 1] root out and to pull down, And to destroy and to overthrow; [Number 2] To build, and to plant. (Jeremiah 1:10)

Jeremiah’s job of “rooting out” and “destroying” was now over. Now, it was time for the vital second part of Jeremiah’s commission—building and planting.

The Bible records God’s promise to His servant David that he would always have a descendant to rule upon his throne, right up until the coming of the Messiah (2 Samuel 7, Jeremiah 33:14-22). God’s promise, as recorded by Jeremiah, was affirmed to be as sure as the sun in the daytime and the moon at night. Many believe, however, that this promise was broken after King Zedekiah was taken into captivity and all his sons were slaughtered. Is that true? Did God lie? Where did the Jewish throne disappear to, after it had been rooted out during the time of Jeremiah?

The answer has everything to do with the second part of Jeremiah’s commission—to build and to plant. To find out more, take a look at the following article: “God Promised David an Everlasting Throne—What Happened to It?”