The discovery of bullae is an exciting moment in any excavation. These miniature stamped clay seals—generally only around one centimeter in diameter, with the tiny names and insignia of various individuals embossed on them—bring “back to life” individuals who have been buried for thousands of years.

Thousands of biblical-era bullae have been discovered on excavations and acquired from the antiquities market. At ArmstrongInstitute.org, we often cite the work of Dr. Eilat Mazar. In her Jerusalem excavations alone, she has uncovered over 200 bullae and seal stamps.

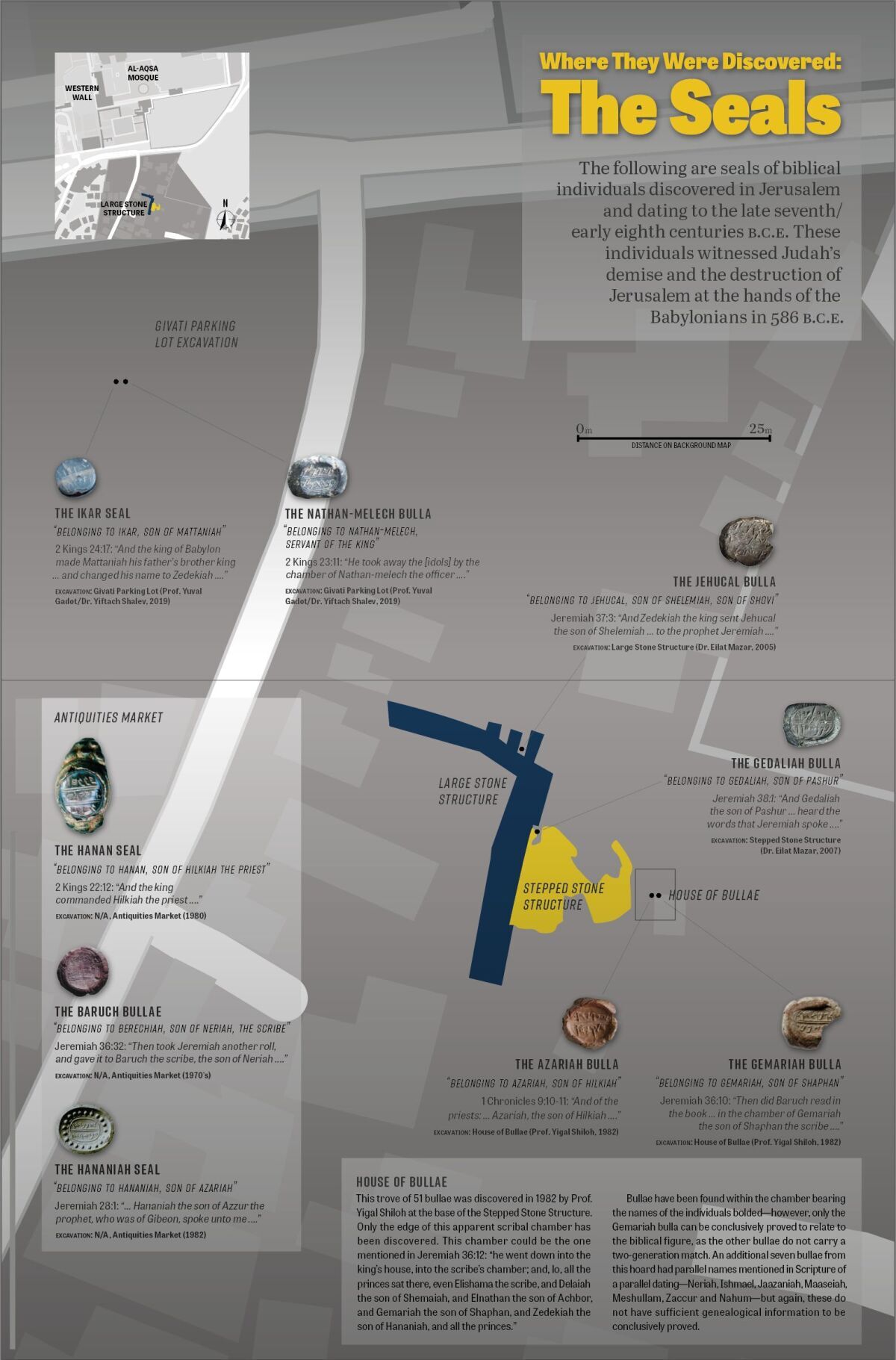

Of the thousands of Hebrew bullae, a significant percentage of them date to the late seventh to early sixth centuries b.c.e.—the period of the Prophet Jeremiah. And of those, about a dozen relate directly to biblical figures, counterparts of the prophet. These tiny artifacts are a snapshot of their lives and work as described in the Bible.

What follows is the story of Jeremiah’s life, as told by bullae—the personal seal impressions of those individuals who knew, supported, instructed, and even attacked the prophet. This is the story of biblical individuals, vividly brought “back to life” through archaeology.

Seal One: Azariah

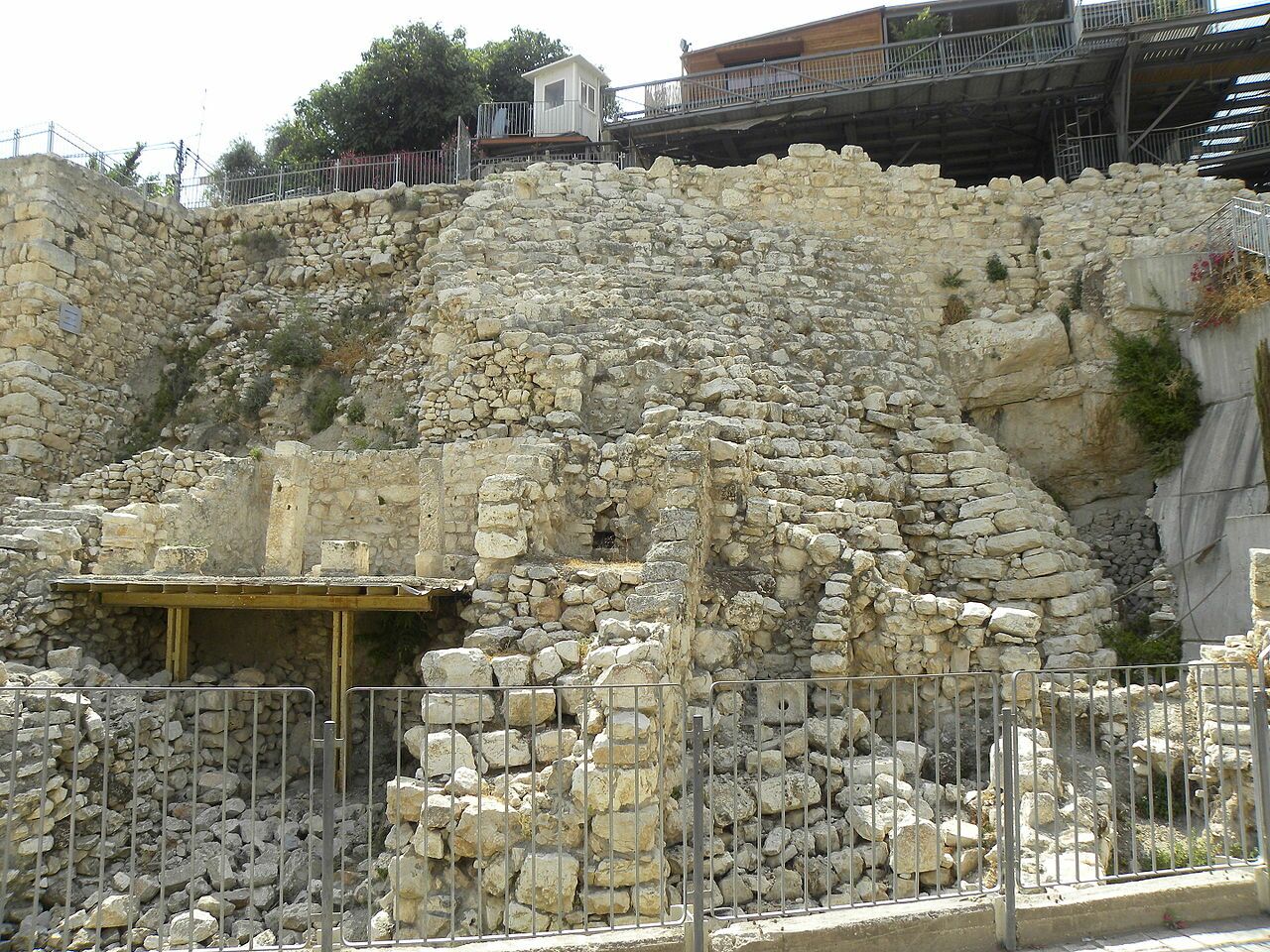

The first stamp in Jeremiah’s story is a bulla inscribed with the text “Belonging to Azariah, son of Hilkiah.” This bulla was discovered during Prof. Yigal Shiloh’s 1982 excavations along the Stepped Stone Structure at the northeastern tip of the City of David.

Azariah was a son of Hilkiah, the famous high priest (1 Chronicles 5:39), who served during the late-seventh century reign of the righteous King Josiah (2 Kings 22). This bulla contains a two-generation match for both high-ranking officials, dates to the correct period, and was found in the corresponding biblical location to these individuals.

Hilkiah was King Josiah’s right-hand man in restoring a brief religious renaissance to Judah. Hilkiah helped the king restore the temple in Jerusalem, which had been desecrated. During this process, Hilkiah discovered a “book of the law” of Moses, which he showed to the king. Corrected by what he read, Josiah sought to turn the nation back to God.

Jeremiah was a young man during the reign of Josiah and ministry of Hilkiah. The young prophet would have witnessed Josiah’s desperate attempts to turn the idolatrous nation of Judah around. And it was partway through the reign of Josiah—13 years, to be precise (Jeremiah 1:2)—that the “word of the Lord” came to Jeremiah.

In Jeremiah 1:1, Jeremiah is identified as the “son of Hilkiah.” Was this Hilkiah the high priest or another Hilkiah? This question has been debated among Bible scholars. The names match, the time periods fit, both were of the priestly class, and the identification could help to explain Jeremiah’s calling (verses 4-10). On the other hand, Hilkiah was a common late-period biblical name. Moreover, if Jeremiah’s father was indeed the high priest, it is strange that he isn’t mentioned as such in the book of Jeremiah—nor the identification of Jeremiah as the high priest’s son in the books of Kings and Chronicles.

Seal Two: Hanan

In 1980, a seal inscribed with the text “Belonging to Hanan, son of Hilkiah the Priest” was acquired on the antiquities market. Although it was not discovered in situ, there is little doubt as to its authenticity. While the Bible does not identify a “Hanan, son of Hilkiah,” experts who have analyzed this seal highlight script similarities with the “Azariah, son of Hilkiah” bulla, and conclude that the seal was most likely made by the same craftsman. As such, this may refer to the same Hilkiah, the high priest—thus identifying Hanan as another son. Again, this seal may also relate to Jeremiah’s father “Hilkiah the priest.”

Seal Three: Nathan-Melech

Inscribed with the text “Belonging to Nathan-Melech, servant of the king,” this bulla was discovered on the northwestern edge of the City of David in 2019 in Prof. Yuval Gadot’s Givati Parking Lot excavations. It matches in name, location, date and royal administration with one of Josiah’s servants. An identical bulla, made by the same seal, had come to light on the antiquities market (1997). The discovery of Gadot’s bulla in a controlled excavation affirms the authenticity of the former.

Nathan-Melech is mentioned only once in the Bible, in the context of King Josiah’s purges of idols. “Then he removed the horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun, at the entrance to the house of the Lord, by the chamber of Nathan-Melech, the officer who was in the court; and he burned the chariots of the sun with fire” (2 Kings 23:11; New King James Version).

As hard as Josiah may have tried, however, he was not able to fully turn the hearts of the people away from idolatry. Josiah’s death spelled the end for Judah—the kingdom’s last four kings would all be successively carried into captivity, culminating in the final destruction of the nation. Foreseeing Judah’s demise upon Josiah’s death, Jeremiah penned the book of Lamentations (2 Chronicles 35:25).

With the removal of Josiah, Judah quickly slid back into idolatrous ways. Jehoahaz became king but reigned only three months before Pharaoh Necho attacked Jerusalem and took him captive. (The existence of this Egyptian pharaoh, Necho ii, is well attested to in ancient inscriptions.) The pharaoh made Jehoahaz’s brother Jehoiakim king; he reigned for 11 years. He too was a wicked king, and was likewise taken captive—this time by Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, who in turn installed Jehoiakim’s 18-year-old son, Jeconiah, as puppet-king.

During all this political turmoil, the Prophet Jeremiah delivered his dramatic and powerful message. On multiple occasions, this solitary “iron pillar” was the victim of frequent, sometimes violent, persecution that nearly broke him (read Jeremiah 20 for insight into one of Jeremiah’s darkest moments). Of course, a man needs help—and that’s what Jeremiah was given.

Our next stamp in Jeremiah’s story is represented by two bullae (impressed by the same original seal stamp).

Seal Four: Baruch

In the 1970’s, two bullae inscribed with the text “Belonging to Berechiah son of Neriah, the Scribe,” were acquired on the antiquities market (part of a trove of 49). The identification of this personality is clear: It refers to Jeremiah’s scribe Baruch, son of Neriah (presented on the seal in the longer theophoric form, with the ending iah; it is not unusual for Hebrew names to be lengthened in this manner).

Given that they represent such a key biblical character, the seals were subject to intense investigation. A scholarly analysis led to the general view that the bullae were forgeries, with three researchers highlighting eight specific areas of concern with the bullae. In 2016, this view was rebutted by a follow-up investigation by three additional scholars. Not only were they able to provide a logical answer for all eight “problematic” areas raised by the earlier research, their analyses highlighted the reverse imprint of wood grain and string on the bullae, which paralleled a fastening technique not known to science until decades after the bullae were purchased—thus indicating their authenticity (see our article “Baruch, Jeremiah’s Scribe: Proved?” for more detail). It is also speculated that these bullae likely came from the “House of Bullae” or nearby “Burnt Room” location.

Baruch is well known as Jeremiah’s right-hand man and scribe. There is even a chapter in the book of Jeremiah aimed directly at Baruch, addressing a particularly difficult time in his life (Jeremiah 45).

A key event involving Baruch during the reign of Jehoiakim occurred alongside a fellow scribe and supporter: Gemariah, son of Shaphan.

Seal Five: Gemariah

Inscribed with the text “Belonging to Gemariah, son of Shaphan,” this bulla was also discovered during Shiloh’s 1982 City of David excavations. It was found along with the “Azariah, son of Hilkiah” bulla. In fact, these were part of a huge trove of 51 bullae discovered in a sixth-century b.c.e. building located at the base of the Stepped Stone Structure. This building became known as the “House of Bullae.”

Jeremiah 36 reveals that the prophet had been put under some kind of house arrest. His assistant, Baruch, had to deliver the prophecies in the temple grounds. Baruch did this “in the chamber of Gemariah the son of Shaphan the scribe” (verse 10).

Gemariah’s son Micaiah heard the warning and was so troubled by it that “he went down into the king’s house, into the scribe’s chamber; and, lo, all the princes sat there, even Elishama the scribe, and Delaiah the son of Shemaiah, and Elnathan the son of Achbor, and Gemariah the son of Shaphan, and Zedekiah the son of Hananiah, and all the princes” (verse 12).

This scribal chamber is a good match with the House of Bullae. Given the 51 bullae found within, this “house” apparently had some kind of scribal function—and of course, it is linked to the same Gemariah mentioned in this scripture. Further, it is located directly below King David’s palace—relating to the upper “king’s house” mentioned in the verse. Several other bullae discovered in the House of Bullae contain the names Elishama, Delaiah, Shelemiah and Hananiah. While these bullae cannot be absolutely confirmed to parallel the biblical characters (they do not contain a two-generation match or a title), it is uncanny that the names of nearly all the individuals referenced in this single verse have been found in the House of Bullae. (An additional seven bullae from this trove parallel names mentioned elsewhere in Scripture, throughout Jeremiah’s lifetime. See our article “‘House of Bullae’ and the Book of Jeremiah” for more information.)

The men were deeply troubled by the prophecies delivered by Baruch. They advised the scribe to go and “hide” while they brought the scroll to King Jehoiakim. Unsurprisingly, Jehoiakim did not appreciate the message. “And it came to pass, when Jehudi [a palace official] had read three or four columns, that he [Jehoiakim] cut it with the penknife, and cast it into the fire …” (verse 23). The account describes how three men in particular—one of which was Gemariah—attempted futilely to stop the petulant king from throwing the scroll into the fire.

But it was too late and the warning fell on deaf palace ears. Baruch would write another scroll, but Jehoiakim’s fate was sealed. King Nebuchadnezzar again invaded the land, took Jehoiakim captive (after a reign of 11 years), and installed his son Jeconiah as king. Jeconiah preceded to reign only three months before Nebuchadnezzar attacked again, deported him, and installed his uncle Zedekiah as king.

Much of this history has been corroborated by archaeology. The Babylonian Chronicle details Nebuchadnezzar’s defeat of Jerusalem at this time, his deportation of Jeconiah, and his appointment of Zedekiah. Several Babylonian inscriptions mention Jehoiakim (one even corroborating the biblical account of his rations administered by the later Babylonian King Evil-merodach; 2 Kings 25:27-30).

Thus began the 11-year rule of Judah’s final king, Zedekiah. And despite the misfortune and national humiliation, Jeremiah’s warnings continued to fall on deaf ears—and the persecution became worse.

Seal Six: Hananiah

The sixth stamp in Jeremiah’s story is etched with “Belonging to Hananiah, son of Azariah.” This seal was discovered on the antiquities market in 1982. It too is considered to be authentic. Its ornate pomegranate border matches precisely with those discovered in excavations of this period, suggesting the work of the same engraver. Jeremiah 28 details one of Jeremiah’s opponents: the false prophet “Hananiah, son of Azur.” Azur is a short version of the name Azariah (again, the interchangeable theophoric “iah”).

Hananiah and Jeremiah had a public showdown in the temple grounds early on in Zedekiah’s reign, when the people still hoped for the return of Jeconiah. Hananiah prophesied that Babylon’s yoke would be broken, and that young King Jeconiah would be reinstated in two years. He yanked off the symbolic yoke Jeremiah was wearing on his neck and snapped it in two. Jeremiah proceeded to prophesy that Babylon’s yoke would be one of iron instead of wood, and that Hananiah would die that same year—which he did.

While the dating and names of the Hananiah seal are a tantalizing link to the biblical false prophet, the evidence is still not sufficient to be certain. For now, this seal remains as a possible, even probable item relating to this irksome figure.

Seal Seven: Jehucal

Zedekiah eventually rebelled against the king of Babylon in favor of an alliance with Egypt. It wasn’t long before Nebuchadnezzar returned with a vengeance to besiege Jerusalem. But there was some cause for hope: Egypt’s pharaoh was fielding an army to fight Nebuchadnezzar. At this time, King Zedekiah sent one of his princes, Jehucal the son of Shelemiah, with a message to Jeremiah: “Pray now unto the Lord our God for us” (Jeremiah 37:3).

In 2005, Dr. Eilat Mazar discovered a bulla inscribed with the words “Belonging to Jehucal, son of Shelemiah, son of Shovi.” This bulla was discovered in the palace ruins above the Stepped Stone Structure in the City of David. It is unusual because it identifies three generations. Jehucal’s grandfather, Shovi (not mentioned in the Bible), must have been a significant figure in the Jerusalemite hierarchy in order for him to have been included on this royal seal.

Jeremiah’s response was unequivocal. There was evidently no national or royal repentance. No change of heart. As we will see, Jehucal himself despised Jeremiah. The prophet declared that the Egyptian army would return to Egypt and that Nebuchadnezzar would return to continue his siege against Jerusalem—ultimately taking the city captive. “Deceive not yourselves,” the prophet warned. “For though ye had smitten the whole army of the Chaldeans [Babylonians] that fight against you, and there remained but wounded men among them, yet would they rise up every man in his tent, and burn this city with fire” (verses 9-10).

With the Babylonians temporarily departed, Jeremiah proceeded to leave Jerusalem for his homeland in Benjamin. As he was leaving, he was violently accosted, accused of defecting to the Babylonians, and thrown into prison, into the torturous “house of Jonathan the scribe” where the prophet nearly died (apparently due to starvation). In response to his protest for fair treatment, King Zedekiah allowed him out into the prison courts, commanding he be given a ration of bread.

Jeremiah would soon have an even closer brush with death, at the hands of Jehucal and a fellow prince.

Seal Eight: Gedaliah

Inscribed with the text “Belonging to Gedaliah, son of Pashur,” this bulla was discovered in 2007 by Dr. Mazar along the edge of the Stepped Stone Structure. It is significant that it was found in the same general location as the bulla of Jehucal, since these two princes are mentioned together in Jeremiah 38.

Jeremiah 38 describes these princes approaching the king, decrying Jeremiah’s effect on the morale of the soldiers. Jeremiah was warning the nation and king to surrender to the Babylonians—this way, they would be spared certain destruction. “Let this man, we pray thee, be put to death,” the princes requested (verse 4). Zedekiah, the people-pleaser, allowed the princes free reign.

The princes retrieved Jeremiah from the court of the prison and took him down to the dungeon of Malchiah. They threw him into the pit, full of “mire,” and left the prophet to sink into the wet muck. Jeremiah would have soon died were it not for the quick rescue by the Ethiopian eunuch Ebedmelech.

Gedaliah may have had a special, long-standing hatred for Jeremiah. His father was named Pashur, and is very likely the same Pashur who beat the prophet and threw him into prison early in his career (Jeremiah 20). Jeremiah prophesied that Pashur would become a “terror” who would witness the deaths of his compatriots—and whose family would be taken captive into Babylon.

Following his rescue, Jeremiah was cleaned up and taken to Zedekiah, who asked the prophet if God had any further instructions. Jeremiah continued to proclaim that if the king would surrender, his life and the lives of his men would be spared. The king was cordial but again rejected Jeremiah’s warning. He allowed the prophet to remain in the prison court “until the day that Jerusalem was taken” (verse 28).

In circa 586 b.c.e., King Nebuchadnezzar and his army ransacked Jerusalem, dismantled the temple, and captured Zedekiah. The last thing the former king saw was his sons lined up and put to death, before his own eyes were gouged out. After this, Zedekiah was taken to Babylon in chains (2 Kings 25:7).

Seal Nine: Ikar

Inscribed with the words “Belonging to Ikar, son of Mattaniah,” this circa early sixth-century b.c.e. seal was found in 2019 in the Givati Parking Lot excavations. It is a beautiful semi-transparent blue stone seal with a rather innocuous inscription. But behind this pretty seal may lie a dark event. The name Zedekiah was given to the king by Nebuchadnezzar. Zedekiah’s original name was Mattaniah (2 Kings 24:17). Thus, this seal—fitting with the location, dating and father’s name—may well have belonged to one of the king’s sons—a son subsequently executed by Nebuchadnezzar.

Sealing a Message of Hope

It is a tragic account, ultimately of sin and rebellion and their consequences. But at its core, Jeremiah’s story carries a hopeful message. And it is fitting that that hopeful message is tied, quite literally, to bullae.

From the beginning, Jeremiah was called for a prophetic mission to “root out and to pull down, And to destroy and to overthrow” (Jeremiah 1:10). But in the very same breath, he was likewise called “To build, and to plant.” While Jeremiah was locked away in Zedekiah’s court of the prison as the Babylonian army was bearing down on Judah, he was given a seemingly preposterous assignment from God: to buy a plot of land in Anathoth, in the territory of Benjamin (Jeremiah 32).

Crazy? It may seem so! The sale of real estate to a prisoner, in a land that was about to be conquered and destroyed, doesn’t seem logical. But that’s what Jeremiah did—buying the land for the equivalent of about $3,000. “And I subscribed the deed, and sealed it, and called witnesses, and weighed him the money in the balances. So I took the deed of the purchase, both that which was sealed, containing the terms and conditions, and that which was open; and I delivered the deed of the purchase unto Baruch the son of Neriah …” (verses 10-12).

The word “sealed” is hatam, the verb form of the Hebrew hotam, the term for a seal stamp, or bulla. This important document was sealed by the stamp of Jeremiah, and probably other witnesses. It may have even included the seal stamp of Baruch. The purchase was then passed on to Baruch, who had been promised divine protection (Jeremiah 45:5), for safekeeping.

Why was this purchase made and stamped in Jeremiah’s name? Jeremiah 32 explains: “For thus saith the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel: Houses and fields and vineyards shall yet again be bought in this land. … Behold, I will gather them out of all the countries, whither I have driven them in Mine anger, and in My fury, and in great wrath; and I will bring them back unto this place, and I will cause them to dwell safely; and they shall be My people, and I will be their God. … Men shall buy fields for money, and subscribe the deeds, and seal them … for I will cause their captivity to return, saith the Lord” (verses 15, 37-38, 44).

Why such an act? “God is sending an inspiring message through that purchase of real estate,” writes aiba founder editor in chief Gerald Flurry in his book Jeremiah and the Greatest Vision in the Bible. “At the very moment Judah was under siege by Babylon, Jeremiah bought a plot of land in Anathoth. … Jeremiah was no prophet of doom. He had the greatest vision in the Bible, clearly focused. If we keep this vision in our minds, we shall never be overcome by discouragement!”

By purchasing this land at Anathoth, even as Jerusalem was being destroyed, Jeremiah was showing the Jews that they would one day return to Jerusalem. He was aware of God’s plans for Jerusalem and was investing in Jerusalem’s future. This gesture provided hope and optimism. Their time in Jerusalem was ending, but God’s prophet was investing in the city! He knew God would once again perform a great and wonderful work in Jerusalem. He knew the Jews would return!

Jeremiah’s message is one of hope for the future—wrapped up and stamped, quite literally, with the bullae of the past.

Sidebar: Inked, not Stamped—The Prophet Himself?

Archaeological excavations have uncovered numerous inscriptions, not only seals and bullae, attesting to the existence of about two dozen individuals from Jeremiah’s day. But what about the prophet? Is there any evidence for Jeremiah himself?

Excavations at Lachish have revealed a hoard of circa 600 b.c.e. ostraca (pottery sherds with ink inscriptions). The majority of these sherds constitute messages passed between military commanders tasked with defending their outposts against the Babylonians. One of the shards, Letter iii, references a warning “from the prophet, saying ‘Beware!’” Could this letter reference the Prophet Jeremiah? It seems “the prophet” must have been well known for him to be referenced as only the prophet, unnamed. Further, Jeremiah had warned against military resistance—and this letter represented military correspondence. The same word is used twice as a warning in the book of Jeremiah.

The name Jeremiah is found on the ostraca, as is Zedek[…?] and Neriah—however, based on the references, it is uncertain if they refer to the biblical figures.

One other particular letter (Lachish xvi) is notable. The tiny Lachish xvi fragment ends with the following words: “… [?]ah, the prophet.” This could fit with any of the three prophets of the book of Jeremiah: Urijah, Hananiah or Jeremiah. But again, what are the chances that it references the most prolific prophet of this time period—the prophet—Jeremiah?