Jerusalem—holy city, right? During the biblical period, it was the location of the temple, the religious authority. Jews who were Sabbath-keepers, kosher-eaters—a markedly different community from foreign entities.

That’s partly true. Jerusalem was ruled by 22 individuals, the majority of whom are outlined in the Bible as rebellious, “bad” kings (as opposed to those who ruled separately over the northern kingdom of Israel—all of whom were such). Even of the 40-odd percent who could be considered largely “righteous,” many of their reigns were pockmarked by catastrophic, faithless decisions that led to either their deaths or the deaths of thousands of their countrymen.

Amid such a track record, would it be surprising to find archaeological evidence of such faithlessness, and even paganism, within ancient Jerusalem?

Dr. Eilat Mazar has been excavating ancient Jerusalem for decades. Most of her time leading excavations has been devoted to two specific sites: the upper City of David and the Ophel (just south of the Temple Mount). Our aiba staff have had the privilege of assisting her in working on and supervising those excavations. Dr. Mazar has now published the results of her 2005–2008 City of David excavations and 2009–2013 Ophel excavations in a series of thorough academic volumes. In this article, we look at some of the specific idols and motifs that have been discovered, and how they closely parallel the biblical account of paganism in Jerusalem.

The Idols

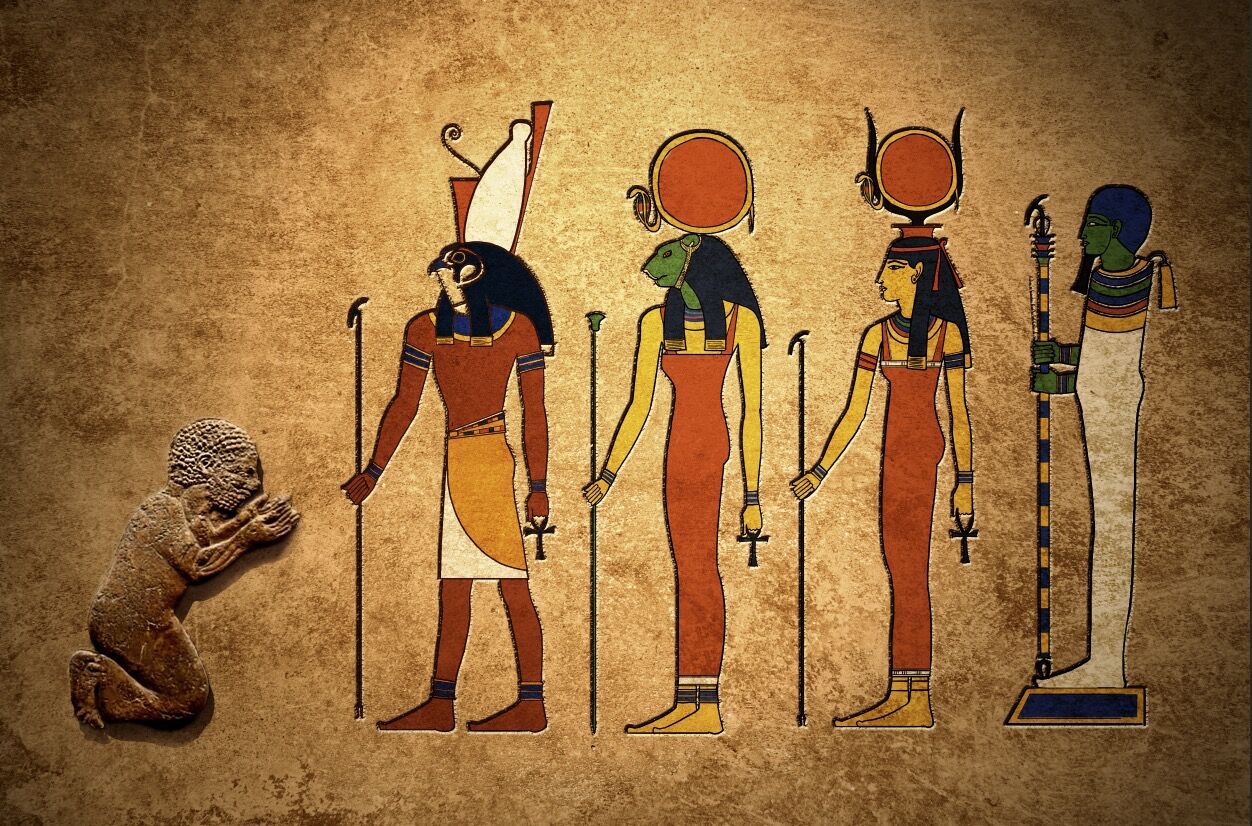

Bes

Childbirth can be a risky “business”—and for the ancients, it was even more dangerous than it is today. As such, childbirth became an extremely pagan ritual across numerous civilizations, featuring various talismans and incantations. An example of this is Bes, one of the chief Egyptian gods of childbirth and child protection (as well as a fighter of evil spirits, killer of snakes). Known as a “grotesque,” Bes is a man-lion figure, often depicted naked. This god was widely worshiped during Egypt’s New Kingdom period (16th–11th centuries b.c.e.).

A pendant figurine of this Egyptian god was discovered by one of our students during Eilat Mazar’s 2012 Ophel excavations. Based on the context of the discovery, it dates to Iron IIA (10th century b.c.e.)—around the time of the United Monarchy of David and Solomon.

This fits with the biblical account. King Solomon’s first wife was an Egyptian princess (1 Kings 3:1). Initially, he “kept” her in the lower City of David, until the temple was finished and a new royal palace for them was built on the Ophel. Thus, it would not be surprising for this figurine to have belonged to her or some other member of the royal harem as a charm to “help” in labor—especially considering that Solomon eventually had 1,000 wives, who led him astray into paganism (1 Kings 11). This influence can explain this and several of the gods described below.

Sekhmet

Sekhmet was an Egyptian lioness-human warrior goddess and goddess of healing. Three clay figurine heads, believed to belong to some form of the goddess, were discovered by Dr. Mazar’s team on the Ophel. Further, two clay naked female torsos were found, one in the City of David and one on the Ophel, believed to belong to the same goddess. These were found in Iron iia strata, and again may relate to influence from Solomon’s wives and a general early slide into paganism.

Petrographic analyses show that the figurines were mostly made from local clay, in or near Jerusalem. Thus, instead of being brought into the country by foreigners, they represent manufacturing by the resident population—of course, in direct contravention to the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:4-6). No Sekhmet figures were discovered following Iron iia—Dr. Mazar speculates the reason for this as follows:

The Bible states that foreign cults [from Solomon’s day] continued into the days of Rehoboam and his son Abijam, being banished in the days of Asa and his son Jehoshaphat, i.e. from the late 10th to the first half of the ninth century b.c.e. … “he [Asa] removed all the idols that his ancestors had made” (1 Kings 15:12). This presumably included the Leviat [lion-goddess/Sekhmet] cult, which was never reestablished.

Anat

Anat was a Canaanite and Egyptian war goddess, also known as “mother of the gods” and “mistress of the sky.” An Iron iia amulet of this goddess was found on the Ophel. Again, this object may relate to the influence of Solomon’s Egyptian wives or of the remaining Canaanite population.

The name Anat is found fairly frequently in the Bible—as a personal name, but particularly as a place name. It is possible that Beth-Anath (House of Anat) and Anathoth (plural of Anat) may have been centers of Anat worship during the Canaanite period, hence their names.

The figurine—like all of the pendants described in this article—is made of faience, a blend of quarz, lime, alkaline salts and coloring. (Egyptian “faience” is a completely different material to standard faience.) In Egypt, objects made of faience were considered to be magical, with the power of rebirth, due to their often-shiny nature.

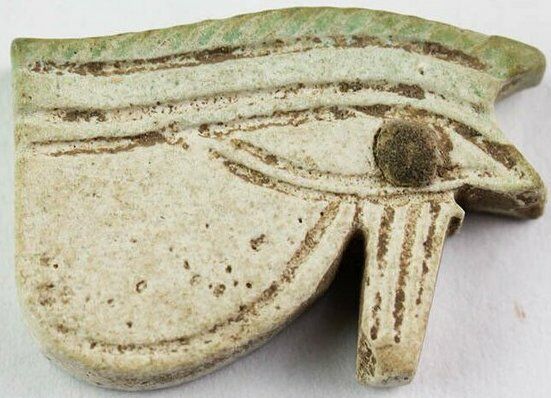

Horus Eyes

Horus Eyes (also known as Udjat Eyes) are the most common form of Egyptian amulet. They are motifs of an eye marked with a line of makeup and what are possibly tears. They were primarily used to ward off evil influences (a very early form of an “evil eye” amulet), and also were believed to have a connection with regeneration. A right-eye amulet is believed to symbolize the sun, while a left-eye amulet symbolizes the moon.

Horus was the sky god of Egypt, son of Isis and Osiris. According to the famous legend, Seth killed Osiris, and Isis became miraculously pregnant after putting together the pieces of his dead body. Their offspring, Horus, was later attacked by Seth, who gouged out his eye. The eye was recovered, and offered to the dead Osiris. (The story of Isis, Osiris, Horus and Seth has links to Nimrod, Shem and ancient Babel—see here for more details.)

Several faience eyes were discovered on the Ophel and in the City of David excavations. They date from Iron iia-b—thus from the beginning of Jerusalem as the Jewish capital to the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians circa 586 b.c.e. A number of Egyptian influences are mentioned in the Bible throughout these periods—Solomon’s wives, as well as Hezekiah’s Egyptian alliance and adoption of motifs (2 Kings 18:21—more on this further down).

Pataikos

This is another similar god to Bes—a grotesque Egyptian god (thought to be linked to Ptah), with a purpose to ward off evil spirits, primarily from small children. (Much of the paganism surrounding the Israelite royalty and population centered around fertility, childbirth and the protection of young.) A small turquoise faience pendant head of this god, with brown hair and portrayed with a scarab on his head, was found on the Ophel. Again, this find dates to Iron Age iia and relates to Egyptian influence.

King Saul is documented as having attempted to fight off an evil spirit (1 Samuel 16). Numerous other scriptural references are made to the influence of “unclean spirits.” A Pataikos amulet was evidently one method (albeit futile, even counterproductive) of countering them, along with the Horus Eye.

This is the second-most common type of Egyptian amulet.

Fertility Figurines

A number of generic nude fertility figurines have been discovered by Dr. Eilat Mazar, particularly on the City of David. These items are of women, either partly or completely naked, with accentuated breasts—and either full-bodied or part-bodied atop miniature pillars. Most, if not all, were locally made from Jerusalem clay, and would have been colored.

Infertile women would acquire these very common items in order to seek divine intervention. Canaanite gods and fertility rites—which were adopted by the Israelites—involved extreme depravity, including prostitution. Some indication is given for this by virtue of these nude figurines. Yet Isaiah 42:16-18 prophesy on this subject that those who “trust in graven images” will be ashamed when they come to know the God who actually heals—whom they had access to.

It is interesting that most of these fertility idols discovered in Jerusalem (and most of the other idols discussed above) have had their heads, legs or pedestals, and breasts snapped off. 2 Kings 23:24 states that the righteous Josiah, one of the last kings of Jerusalem, destroyed the “images and the idols” in Jerusalem. This would certainly have been done to large items—and also, as seen by the condition of these gods and goddesses, to the small.

The Seals

A number of official seals and seal impressions have been discovered in Jerusalem, also bearing pagan imagery. Apart from impressions known to be Judahite (the Hezekiah lmlk seals), no impressions or bullae are included below (as they could constitute foreign correspondence). Instead, we focus mainly on the seals themselves that were discovered and used within Jerusalem. Firstly though, Hezekiah’s lmlk seals.

lmlk Seals

Literally thousands of these seal impressions have been found around Israel, with numerous examples from Dr. Mazar’s excavations in Jerusalem. They adorned the handles of specific Judahite vessels. There are five main types of design, each displaying some form of either a winged scarab beetle or winged sun. All of them bear the word lmlk, or “to the king”—and on many of them is the name of a different Judahite city. They date specifically to the reign of King Hezekiah, and particularly match his two main styles of personal seal impression—one displaying a winged scarab beetle in the center, rolling a sun disk; the other, displaying a winged sun. Here, we focus only on the winged scarab lmlk seal and corresponding seal impression of the king.

Scientists are uncertain of just what these seal-stamped lmlk jars were for. One theory is that they were a part of siege preparations before the invasion of Sennacherib’s Assyrian army. Other theories are that they were intended to contain taxes, military rations, or serve some other kind of general administrative purposes during Hezekiah’s reign.

The Bible makes clear that Hezekiah started his reign with incredible, righteous gusto (2 Kings 18:1-8). But during the middle part, things took a turn. The Assyrian army swept into the land, overthrowing dozens of cities and very nearly capturing Jerusalem, were it not for divine intervention. A number of clues indicate that up to and during that time, Hezekiah and the nation had turned away from God. One of the Assyrian commanders accused Hezekiah of depending on his alliance with Egypt (verses 20-21)—an alliance specifically warned against by the Prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 30 and 31). Hezekiah’s official motifs—particularly the winged scarab lmlk seals and his winged scarab personal seal—are evidence of this Egyptian influence.

The winged scarab is a deeply pagan motif. The scarab represents the god Khepri who, as the beetle rolls a ball of dung, rolls the sun-god Ra across the sky, collecting souls and transporting them to the underworld after sunset. Added wings were also a common Egyptian motif. These images would have circulated around Judah in the years prior to the Assyrian onslaught, as Hezekiah forged ties with the Egyptians, adopting their pagan symbolism.

Following the Assyrian invasion, Hezekiah’s repentance, and God’s intervention, there appears to be an about-face in Hezekiah’s motifs. The scarab is completely nixed, and symbolism actually seems to relate to what occurred at the time of Hezekiah’s miraculous healing (2 Kings 20). This is noted on a bulla belonging to the king, discovered by Dr. Mazar. More can be read about this bulla, and the general about-face in religion and politics, here.

Baal Seal

This seal, in the form of a scarab, was found in the City of David, and dates somewhere within circa 1070–900 b.c.e. The image on the underside of the seal depicts a figure with a horned, high hat and outstretched wings, standing on top of a walking lion. This figure is known to be the god Baal-Seth. More properly, he is a fusion of the Canaanite god Baal and the Egyptian god Seth (due to the Seth hat).

Baal is mentioned 62 times in the Bible—the most-referenced pagan god. This was the primary god the Israelites continued to stubbornly worship in droves (especially due to the prevalence of his worship among the native Canaanite population, whom the Israelites failed to drive out; Judges 1 through Judges 2:13).

Several verses reference Baal worship in Jerusalem (2 Kings 23:4-5; Jeremiah 11:13; Zephaniah 1:4). It is, therefore, unsurprising to find an official seal and object of reverence for this god within the royal city.

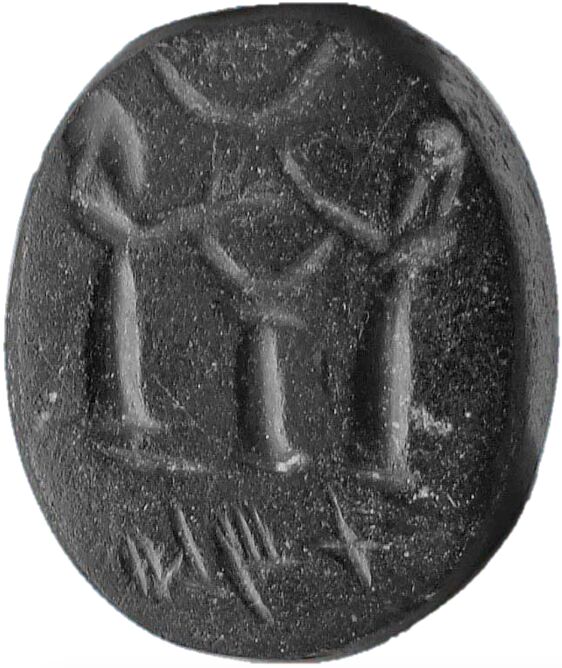

Shelomith Seal

This shiny black stone seal was discovered in the City of David in a layer dating to the Babylonian period (circa 586–539 b.c.e.). Based on the inscription style and the imagery, however, it best dates to the seventh century b.c.e. It contains the biblical Hebrew name Shelomith. It was of local provenance and, significantly, displays Assyrian-style imagery.

Two worshipers, with their hands aloft, face an altar. Above them is a crescent shape—the symbol for the moon god, Sin. This is a particularly ancient god, dating back to early Mesopotamian worship in Sumer around 1,500 years earlier (again, congruous with the land of Shinar, and matching with the date of the story of Nimrod).

The Bible clearly relates that during this seventh century b.c.e. period, Jerusalem was yoked—on and off—in tribute to Assyria (e.g. 2 Kings 15-21). The seal may thus relate to a princess or female official who had sympathies toward Assyria or the Assyrian religion.

Lamassu Seal

This black limestone seal, similar to the one above, also appears to date to the seventh century b.c.e. It contains no inscription, but again, depicts an Assyrian-style scene. Front and center is a winged lamassu/sphinx-type creature. Above is a crescent moon, again symbolizing the god Sin. This likely relates to the same Assyrian political context described in the above Shelomith seal.

The central lamassu image most likely represents a protective deity. These winged beings, quite a common ancient motif, hearken to the biblical imagery of angelic creatures known as cherubim—winged protective angels who stand guard at the throne of God, covering it with their wings (i.e. Exodus 25:18-22; also Genesis 3:24, where they protect the way to the tree of life). The Assyrian and Persian lamassu, and Egyptian sphinx, then, likely represent perversions of these angels.

Scarabs

A number of other general scarab seals were found on the Ophel and in the City of David, dating to the early part of the Judahite monarchy, with various motifs engraved on their bases. As stated above, the scarab was a sacred Egyptian motif related to the gods Khepri and Ra, symbolizing rebirth and renewal of souls.

Seals were only carried by high officials. As such, these scarabs represent members of government serving in Jerusalem. Take a look at the below image to see one of the scarabs discovered on the Ophel excavation. This one features rams’ heads—a representation of the god Amun-Ra (a combination of the god who “created the universe” and the sun god).

Pagan Jerusalem

Evidently, ancient Jerusalem wasn’t as overly “righteous” as it might have seemed. As we wrote about recently, Dr. Mazar’s excavations have also revealed that while ancient Jerusalem’s population largely ate kosher (“clean”) animals, they also consumed a significant number of “unclean” animals such as pig and catfish.

Despite these perhaps surprising discoveries, the pagan idols, motifs, foreign influences and unclean food all directly parallel the biblical account. They also provide the very reason why Judah and Jerusalem finally fell to the Babylonians circa 586 b.c.e., in a brutal takeover of the capital city—just as relayed by Israel’s prophets.